Most weightlifters consider the back squat the “king of exercises.”

Part of the reason it reigns supreme is it’s so freaking hard, making a big back squat a rite of passage of sorts for gym-goers.

The barbell back squat requires just about every major muscle group in your body to work in concert to generate a tremendous amount of force, as well as near picture-perfect form if you’re ever going to put up impressive numbers.

What’s more, the back squat benefits just about anyone, whether you train for size, strength, sports performance, functionality, or general health.

Of course, to reap the bar back squat’s benefits, you have to do it correctly. Fortunately, that’s precisely what you’ll learn in this article.

By the end, you’ll know what the back squat is, how to do the back squat with proper form, why it’s beneficial, which muscles it works, the best back squat alternatives, and more.

What Is the Back Squat?

The back squat (also known as the “barbell back squat,” “bb back squat,” or often just “the squat”) is a lower-body exercise that involves squatting with a barbell lying across your upper back.

There are two options when it comes to bar placement on your upper back:

- The high-bar position, where the bar rests on your upper traps

- The low-bar position, where the bar rests between the mid traps and rear deltoids

Because the low-bar back squat allows you to leverage your large posterior chain muscles (the muscles on the back of your body, including your glutes, hamstrings, and lower back) better and lift more weight than the high-bar back squat, I recommend beginners start with the low-bar variation.

As such, that’s the squat variation we’ll focus on in this article (and the version I recommend in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger).

However, if you find the low-bar squat uncomfortable on your shoulders and wrists, the high-bar squat is a perfectly viable alternative.

How to Do the Back Squat

To learn how to back squat, split the exercise into three parts: set up, descend, and squat.

Step 1: Set Up

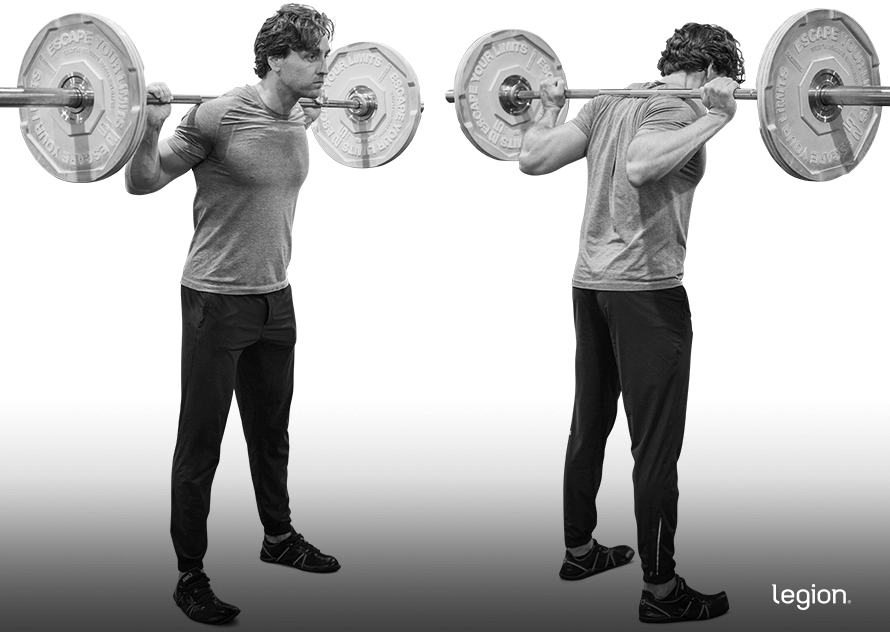

Adjust the hooks in a squat or power rack so the bar is at the height of your midchest like this:

Step under the bar, pinch your shoulder blades together, and rest the bar directly above the bony ridges on the bottom of your shoulder blades.

Grip the bar with your palms facing forward, thumbs on top of or wrapped around the bar, and your hands about 4-to-8 inches wider than shoulder-width apart. You may need to narrow or widen your grip to find the correct position, where the weight rests almost entirely on your back muscles, not in your hands or on your spine.

Unrack the bar by standing up and taking one step back with each foot (one at a time). Adjust your feet so they’re a little wider than shoulder-width apart and point your toes out about 20-to-25 degrees (around one and eleven o’clock).

Here’s what you should look like from the front and back:

Step 2: Descend

Take a deep breath into your stomach, push your chest out, brace your core, and sit down by bending at the knees and hips at the same time. Keep sitting down until your thighs are parallel to the floor or slightly lower.

Here’s how you should look at the bottom of the back squat:

Step 3: Squat

Drive your feet into the floor, ensuring your shoulders move upward at the same rate as your hips. About halfway up, push your hips forward and underneath the bar to return to the starting position.

Here’s how it should look when you put it all together:

Sets and Reps for the Bar Back Squat

For most men looking to gain muscle and strength, 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps works well. For women with similar goals, 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps is more fitting.

If gaining maximum strength is your priority, doing sets in a lower rep range (e.g., 1-to-5) will produce the best results, provided you’re following a well-structured training plan.

And if you’re completely new to weightlifting, starting in a higher rep range, such as 8-to-10 reps, can help you “groove in” proper technique while minimizing your risk of injury. However, once you’ve learned how to back squat with good form, graduating to a lower rep range will likely yield better results.

Common Barbell Back Squat Mistakes

1. Your knees fall inwards.

The problem: Your knees collapse in toward one another as you stand up in the squat.

The fix: Imagine spreading the floor apart with your feet by driving your feet into the ground and away from each other (though they shouldn’t actually move). This prevents your knees from caving inward, increases the activation of your glutes, and enables you to lift more weight with a lower risk of pain or injury.

2. Your hips shoot up.

The problem: Your hips rise faster than your shoulders as you stand up in the squat, causing you to lose balance and the bar path to deviate forward.

The fix: Drive your back into the bar as you begin to stand up to prevent you from leaning too far forward. Using this “cue” also ensures that your quads, glutes, and hamstrings work together to help you lift heavy loads with good form.

3. You don’t break parallel.

The problem: You begin to stand up from the bottom position before your hip crease is the same height as the top of your knees or lower, limiting the exercise’s muscle- and strength-building potential.

The fix: Continue lowering your body until your hip crease is at least level with the top of your knees. If mobility issues prevent you from reaching this depth, squat as low as you comfortably can and work on flexibility exercises for your hips, ankles, and calves.

The Best Back Squat Alternatives and Variations

If you can’t or don’t want to barbell back squat, here are the best alternatives and variations to do instead.

1. Front Squat

The front squat trains the quads about as effectively as the back squat, even when you use up to 20% less weight. What’s more, the front squat also places less compressive forces on your knees and lower back, which make it a particularly good alternative to back squatting for those with knee or back issues.

2. Bulgarian Split Squat

Research shows The Bulgarian split squat is a great exercise for your entire lower body, and because it trains just one leg at a time, it’s useful for finding and fixing muscle or strength imbalances.

3. Hack Squat

The hack squat is another top-tier bar back squat alternative because it trains all your lower-body muscle groups through a full range of motion without stressing your knees and back as much as other free-weight squatting exercises.

4. Goblet Squat

Research shows that the goblet squat is an effective exercise for training all your lower-body muscles, particularly your quads. Because you hold the weight in your hands rather than across your shoulders, it’s easier on your back than other squat variations and makes getting into a squat position easier, which is beneficial for those with injury or mobility concerns.

However, you can’t lift as much weight with the goblet squat as you can with the back squat, making the exercise less effective for gaining muscle and strength.

5. Leg Press

Since the leg press doesn’t require you to balance or support weight with your upper body, it allows for heavier loads compared to other back squat alternatives. It’s also significantly less fatiguing, so you can do it more often without burning out.

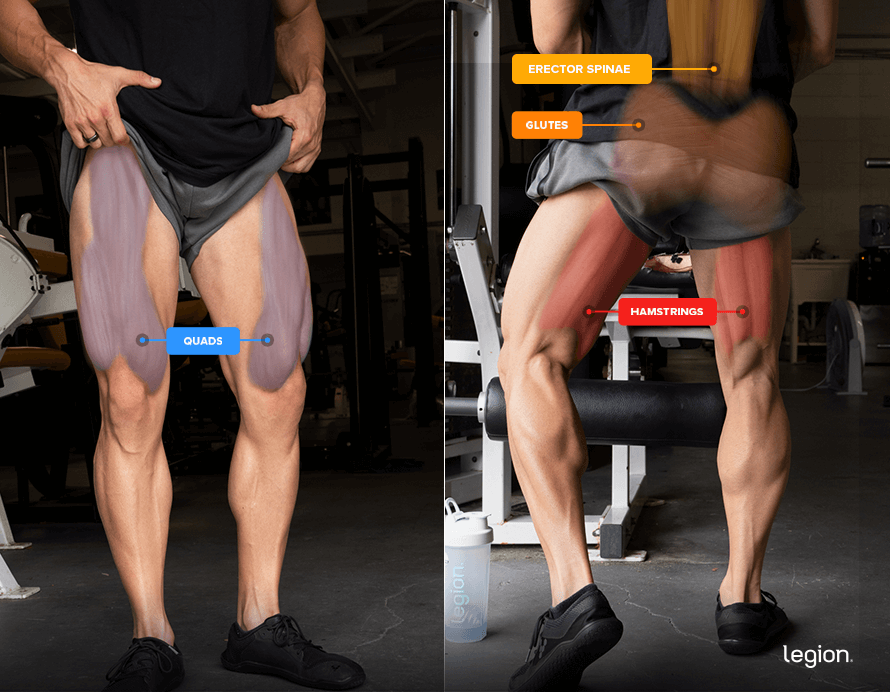

Muscles Worked by the Back Squat

The main muscles worked by the back squat are the . . .

- Quadriceps

- Hamstrings

- Glutes

- Erector spinae

It also trains your lats, traps, calves, and abs to a lesser degree, too.

Here’s how the main muscles worked by the back squat look on your body:

The Benefits of Back Squatting

1. It trains several major muscle groups.

The back squat is a unique exercise in that it trains almost every major muscle group in your body, excluding arms, chest, and shoulders.

Specifically, it helps develop your quadriceps, glutes, hamstrings, erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, calves, and abs.

2. It improves athletic performance.

The back squat improves your athletic performance in three ways:

- It helps you develop lower-body power, speed, and strength.

- It trains hip extension (moving your thighs away from your upper body), which improves your performance in any sport that involves running, jumping, climbing, throwing, sidestepping, and landing.

- It helps you build lower–body stability, making you less prone to injury, so that you can spend more time competing and less time sidelined.

3. It allows you to lift heavy weights.

Generally speaking, the more weight you lift, the more strength and muscle you gain.

The back squat allows you to use heavier weights than most other exercises and causes greater activation of many “supporting” muscle groups, which makes it a fantastic way to build whole-body muscle, strength, and coordination.

It also allows you to progress regularly, which is the best way to maximize the muscle- and strength-building benefits of weightlifting.

Back Squat: FAQs

FAQ #1. What is the difference between squats and back squats?

“Squats” are a general term for exercises that involve lowering the body into a sitting position and then rising back up.

There are various types of squats, each with its own technique and benefits. The back squat, specifically, is a type of squat where you rest a barbell on your upper back during the movement. This contrasts with other squat variations like the front squat, where you hold the barbell on front of your shoulders, or the goblet squat, where you hold a dumbbell in front of your chest.

FAQ #2. Are back squats good for you?

Yes, back squats are highly beneficial for various reasons.

They’re a compound exercise that trains multiple muscle groups simultaneously including the quads, hamstrings, glutes, lower back, and core. This makes them effective for building whole-body strength, muscle mass, and power. Back squats can also help improve balance, mobility, and functional strength, which are beneficial for daily activities and sports.

Additionally, back squatting burns more calories than most weightlifting exercises, so they may boost fat loss in some scenarios.

FAQ #3. What’s the world record back squat?

The heaviest squat ever performed at an officiated event is 1,311 pounds (~595 kilograms), which was performed by Nathan “Tractor” Baptist in 2021.

While it’s definitely not cause to discount this effort, Baptist set his world record back squat while wearing several pieces of supportive equipment that helped him lift such a howling weight.

Some people also question whether this is a legitimate back squat world record because footage of the feat makes it look as though Baptist didn’t squat deep enough (his hip crease didn’t go below his knee joint), but the judge at the event ruled that he hit the required depth for the lift to count.

Scientific References +

- Yavuz, Hasan U., and Deniz Erdag. “Kinematic and Electromyographic Activity Changes during Back Squat with Submaximal and Maximal Loading.” Applied Bionics and Biomechanics, vol. 2017, 2017, pp. 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9084725. Accessed 1 Mar. 2019.

- Yavuz, Hasan U., and Deniz Erdag. “Kinematic and Electromyographic Activity Changes during Back Squat with Submaximal and Maximal Loading.” Applied Bionics and Biomechanics, vol. 2017, 2017, pp. 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9084725. Accessed 1 Mar. 2019.

- Yavuz, Hasan Ulas, et al. “Kinematic and EMG Activities during Front and Back Squat Variations in Maximum Loads.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 33, no. 10, 29 Jan. 2015, pp. 1058–1066, www.growkudos.com/publications/10.1080%25252F02640414.2014.984240/reader, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.984240.

- Gullett, Jonathan C, et al. “A Biomechanical Comparison of Back and Front Squats in Healthy Trained Individuals.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2009, pp. 284–292, journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2009/01000/A_Biomechanical_Comparison_of_Back_and_Front.41.aspx, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31818546bb.

- Jones, Margaret T, et al. “Effects of Unilateral and Bilateral Lower-Body Heavy Resistance Exercise on Muscle Activity and Testosterone Responses.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 4, Apr. 2012, pp. 1094–1100, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e318248ab3b.

- DeFOREST, Bradley A., et al. “Muscle Activity in Single- vs. Double-Leg Squats.” International Journal of Exercise Science, vol. 7, no. 4, 2014, pp. 302–310, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27182408/.

- Deniz Erdağ, and Hasan Ulaş Yavuz. “Evaluation of Muscle Activities during Different Squat Variations Using Electromyography Signals.” ResearchGate, unknown, 2020, www.researchgate.net/publication/337400852_Evaluation_of_Muscle_Activities_During_Different_Squat_Variations_Using_Electromyography_Signals.

- Collins, Kyle S., et al. “Differences in Muscle Activity and Kinetics between the Goblet Squat and Landmine Squat in Men and Women.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. Publish Ahead of Print, 2 Aug. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000004094.

- Coratella, Giuseppe, et al. “The Activation of Gluteal, Thigh, and Lower Back Muscles in Different Squat Variations Performed by Competitive Bodybuilders: Implications for Resistance Training.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 2, 1 Jan. 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7831128/, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020772. Accessed 2 May 2021.

- Myer, Gregory D., et al. “The Back Squat.” Strength and Conditioning Journal, vol. 36, no. 6, Dec. 2014, pp. 4–27, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4262933/, https://doi.org/10.1519/ssc.0000000000000103.

- Neto, Walter Krause, et al. “Gluteus Maximus Activation during Common Strength and Hypertrophy Exercises: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, vol. 19, no. 1, 24 Feb. 2020, pp. 195–203, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7039033/.

- Kirkpatrick, John , and Paul Comfort. Strength, Power, and Speed Qualities in English Junior Elite Rugby League Players. Dec. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182804a6d.

- Wisloff, U, et al. “Strong Correlation of Maximal Squat Strength with Sprint Performance and Vertical Jump Height in Elite Soccer Players.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 38, no. 3, 1 June 2004, pp. 285–288.

- Seitz, Laurent B., et al. “Increases in Lower-Body Strength Transfer Positively to Sprint Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine, vol. 44, no. 12, 25 July 2014, pp. 1693–1702, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0227-1.

- Delgado, Jose , et al. Comparison between Back Squat, Romanian Deadlift, and Barbell Hip Thrust for Leg and Hip Muscle Activities during Hip Extension. July 2019, https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003290.

- Behrens, Matthew J, and Shawn R Simonson. “A Comparison of the Various Methods Used to Enhance Sprint Speed.” Strength and Conditioning Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, Apr. 2011, pp. 64–71, https://doi.org/10.1519/ssc.0b013e318210174d.

- Gallego-Izquierdo, Tomás, et al. “Effects of a Gluteal Muscles Specific Exercise Program on the Vertical Jump.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 15, 1 Jan. 2020, p. 5383, www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/15/5383, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155383.

- Bartlett, Jamie L., et al. “Activity and Functions of the Human Gluteal Muscles in Walking, Running, Sprinting, and Climbing.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, vol. 153, no. 1, 12 Nov. 2013, pp. 124–131, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22419.

- Plummer, Hillary A., and Gretchen D. Oliver. “The Relationship between Gluteal Muscle Activation and Throwing Kinematics in Baseball and Softball Catchers.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 28, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 87–96, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e318295d80f. Accessed 23 Sept. 2019.

- Houck, Jeff. “Muscle Activation Patterns of Selected Lower Extremity Muscles during Stepping and Cutting Tasks.” Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, vol. 13, no. 6, Dec. 2003, pp. 545–554, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1050-6411(03)00056-7. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019.

- Struminger, Aaron H., et al. “Comparison of Gluteal and Hamstring Activation during Five Commonly Used Plyometric Exercises.” Clinical Biomechanics, vol. 28, no. 7, Aug. 2013, pp. 783–789, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0268003313001526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.06.010. Accessed 28 Mar. 2019.

- ESCAMILLA, RAFAEL F. “Knee Biomechanics of the Dynamic Squat Exercise.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 33, no. 1, Jan. 2001, pp. 127–141, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200101000-00020.

- Hartmann, Hagen, et al. “Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine, vol. 43, no. 10, 3 July 2013, pp. 993–1008, www.deepdyve.com/lp/springer-journals/analysis-of-the-load-on-the-knee-joint-and-vertebral-column-with-zkgXYldF90, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0073-6.

- “N.S.C.A. POSITION PAPER: The Squat Exercise in Athletic Conditioning: A Position Statement and Review of the Literature.” Strength & Conditioning Journal, vol. 13, no. 5, 1 Oct. 1991, pp. 51–58, journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Citation/1991/10000/N_S_C_A__POSITION_PAPER__The_Squat_Exercise_in.11.aspx.

- McLaughlin, T. M., et al. “Kinetics of the Parallel Squat.” Research Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 2, 1 May 1978, pp. 175–189, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/725284/. Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.

- Myer, Gregory D, et al. “Real-Time Assessment and Neuromuscular Training Feedback Techniques to Prevent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Female Athletes.” Strength and Conditioning Journal, vol. 33, no. 3, June 2011, pp. 21–35, https://doi.org/10.1519/ssc.0b013e318213afa8.

- Miletello, Wendy M, et al. “A Biomechanical Analysis of the Squat between Competitive Collegiate, Competitive High School, and Novice Powerlifters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 23, no. 5, Aug. 2009, pp. 1611–1617, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181a3c6ef.