Of all the workout supplements on the market, creatine is one of the best.

It’s the most well-researched molecule in all of sports nutrition—the subject of hundreds of scientific studies—and its benefits are clear: it helps you gain muscle and strength faster and boosts endurance and recovery, and it does it all naturally and safely.

Therefore, deciding whether or not to take creatine is simple: You should. Deciding which type to take, however, is a trickier riddle to unravel.

That’s because supplement companies constantly concoct new kinds of creatine and claim each is more potent than the last.

How much of this is marketing bluster, though? Is each new variant really the “best creatine on the market?”

Get an evidence-based answer in this article.

(Or if you’d prefer to skip all of the scientific mumbo jumbo and you just want to know if you should take creatine or a different supplement to reach your goals, no problem! Just take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

Table of Contents

+

What Is Creatine?

Creatine is a natural compound made up of the amino acids L-arginine, glycine, and methionine. Our body can produce creatine naturally, but it can also absorb and store creatine found in various foods like meat, eggs, and fish.

How Does Creatine Work?

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the most basic unit of cellular energy. When cells use ATP, they split it into smaller molecules, and when they’re finished, they “reassemble” these fragments back into ATP for reuse.

The more ATP your cells can store and the faster your body can regenerate ATP, the more “work” it can do.

Creatine acts as an energy reserve for your cells by accelerating ATP production. It does this by donating a molecule to an ATP precursor called adenosine diphosphate (ADP), which allows it to be rapidly converted into ATP.

Basically, creatine helps your body more efficiently recycle ATP so that it can be used to quickly power muscular contraction.

While creatine helps you replenish your ATP stores quickly, these stores are limited. Once they deplete, the body turns to glucose or fatty acids to continue producing ATP.

Supplementing with creatine greatly increases your creatine stores, particularly in your muscles, which is why it boosts muscle growth, increases strength and power, improves anaerobic capacity, reduces fatigue, lessens muscle damage and soreness after exercise, alters the expression of genes related to hypertrophy, and preserves muscle after grueling workouts.

What Is the Best Creatine Supplement?

Creatine monohydrate is the most commonly studied and used form of creatine, though many more varieties are available.

Supplement companies often market these novel forms of creatine as superior to monohydrate and charge a corresponding markup. Is the cost justified, though?

Let’s take a look at the efficacy of each according to science.

Creatine Citrate

When creatine binds to citric acid, it creates creatine citrate. Research shows that creatine citrate offers no additional benefits compared to monohydrate.

Creatine Malate

Creatine malate is creatine bound with malic acid. Preliminary research suggests that malic acid may have some performance-boosting effects, but there’s nothing to suggest it will work better in conjunction with creatine.

Creatine Ethyl Ester

Some people claim that creatine ethyl ester is more bioavailable than other forms of creatine, but research shows it’s less effective than monohydrate (and on par with a placebo).

The reason for this is when you ingest creatine ethyl ester, it’s quickly converted into the inactive substance creatinine, which confers none of creatine’s benefits. (This makes creatine ethyl ester one of the worst forms you can take.)

Liquid Creatine

Liquid creatine is a form of creatine (normally monohydrate) that’s already dissolved in water.

Supplement companies claim this makes it more effective than powdered forms by improving absorption, reducing bloating, and decreasing how much you need to take to experience benefits.

Research shows that liquid creatine is a dud, though, likely because suspending creatine in liquid for several days causes it to break down into the inactive substance creatinine. In effect, you’re just drinking glycine mixed with water.

Creatine Nitrate

Creatine nitrate is a form of creatine bound with a “nitrate group.” While nitrates have performance-enhancing properties, research shows that creatine nitrate is no more effective than monohydrate.

Creatine Magnesium Chelate

Creatine magnesium chelate is a form of creatine bound to magnesium.

Magnesium plays a role in creatine metabolism, which is why some people believe it could increase creatine’s effectiveness.

Research shows that creatine magnesium chelate and monohydrate improve performance similarly, though creatine magnesium chelate may cause less water weight gain.

Buffered Creatine

“Buffered creatine” is a form of creatine monohydrate with a higher pH (it’s less acidic). Supplement companies claim this makes it superior to regular monohydrate, but research shows they’re equally effective.

Creatine Pyruvate

Creatine pyruvate is creatine bound with pyruvic acid.

Studies show that creatine pyruvate produces higher levels of creatine in your blood than monohydrate but is no more easily absorbed, which means it’s unlikely to be more effective.

Creatine Monohydrate

Creatine monohydrate is the most well-studied and scientifically supported sports supplement available today. Research routinely shows that creatine monohydrate is safe to use and reliably boosts your athletic performance as much or more than other forms.

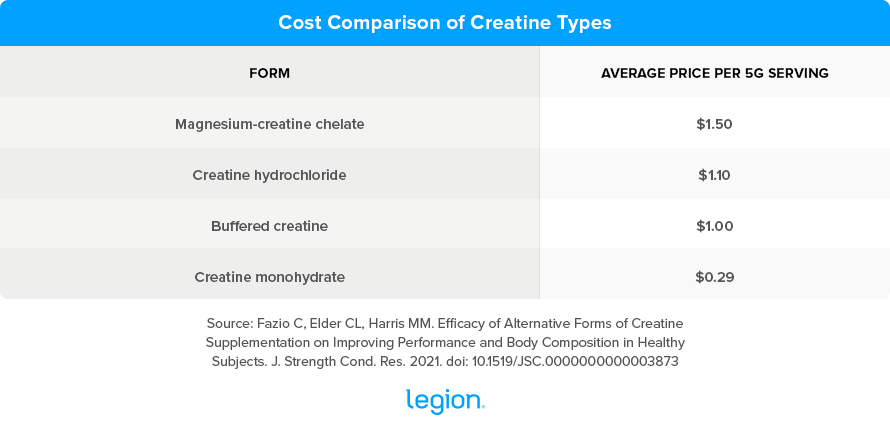

It’s also the most cost-effective. In a systematic review conducted by scientists at the University of Colorado, researchers examined the results of 17 studies and found that most forms of creatine boost performance to a similar degree, but creatine monohydrate is 3-to-5 times more affordable. Here’s part of their cost analysis:

Thus, creatine monohydrate is the gold standard of creatine, and nothing’s likely to dethrone it anytime soon. That’s why it’s the type I use in my creatine powder, gummies, and my post-workout supplement, Recharge.

(If you aren’t sure if creatine monohydrate powder, gummies, or Recharge is right for you or if another supplement might better fit your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

FAQ #1: What are creatine’s side effects?

Creatine is generally well tolerated and causes few adverse side effects.

Some people experience stomach cramps if they drink insufficient water, and diarrhea if they take too much (more than 20 grams) at once.

You can avoid these side effects by drinking to thirst and taking no more than five grams of creatine at a time.

In the past, some people also reported feeling bloated when they took creatine, but as processing methods have greatly improved, this is much less of a problem now than it once was.

FAQ #2: What’s the best creatine for men?

The best creatine for men is any form of powdered creatine monohydrate. That said, you may prefer a supplement containing micronized creatine monohydrate if you have a sensitive stomach since it’s less likely to cause gastrointestinal issues.

And If you want a 100% natural source of micronized creatine monohydrate, try Recharge.

FAQ #3: What’s the best creatine for women?

Women often shy away from creatine because they’re afraid of “getting bulky” or bloating. As we’ve already seen, bloating is no longer an issue and getting bulky never was.

Since creatine works the same in both sexes, women’s best creatine supplements are the same as men’s: any form of creatine monohydrate.

FAQ #4: When is the best time to take creatine?

Many people think there’s a “best time to take creatine,” but research shows it works perfectly well when you take it at any time of the day.

FAQ #5: What is the best creatine for muscle growth?

Most all creatine supplements are equally effective, but creatine monohydrate is significantly cheaper, which is why I think it’s the best creatine for building muscle.

FAQ #6: What’s the best creatine monohydrate?

There are two forms of creatine monohydrate: Micronized and non-micronized. Both boost performance equally—the only difference is that micronized creatine monohydrate is processed more thoroughly, making it more water-soluble and easier to digest. This makes it easier to mix and a better option for people with sensitive stomachs, but it’s often more expensive than non-micronized creatine.

As such, there’s no “best type of creatine” for everyone—choose whichever best suits your needs.

FAQ #7: Do you need to cycle creatine?

No.

When you supplement with creatine, your body reduces its natural production, but it doesn’t impact your endocrine system like steroids.

Producing creatine is demanding for the body, and reducing this burden may even be healthful. And if you cease supplementation with creatine, your body resumes its regular production.

FAQ #8: How do you take creatine?

Research shows that supplementing with five grams of creatine per day is optimal.

When you first start taking creatine, you can “load” it by taking 20 grams per day for the first 5-to-7 days (followed by the “maintenance” dosage of 5 grams per day).

You don’t have to load, but studies show that it causes the creatine to accumulate faster in your muscles, helping you reap its benefits sooner.

FAQ #9: Is creatine bad for your kidneys?

No.

If you have healthy kidneys, creatine doesn’t harm your kidneys.

Even if you have impaired kidney function, you’re unlikely to experience any problems. In one study, 20 grams of creatine per day caused no harm to someone with one slightly damaged kidney. That said, if you have any kidney issues, check with your doctor before you start supplementing with creatine.

One of the reasons people still believe creatine stresses the kidneys relates to a substance known as “creatinine,” which your body produces when it metabolizes creatine.

In sedentary people not supplementing with creatine, elevated creatinine levels can indicate kidney problems. You should expect high creatinine levels if you exercise regularly and supplement with creatine, though.

FAQ #10: Should you take creatine while dieting to lose weight?

Yes.

Supplementing with creatine while in a calorie deficit is smart because it helps you retain your muscle and strength, which is vital for improving your body composition.

FAQ #11: Does creatine cause baldness?

One study conducted by scientists at Stellenbosch University found that creatine raised levels of dihydrotestosterone or DHT, a hormone that hastens hair loss in susceptible men.

Specifically, they found that the normal protocol of taking 20 grams of creatine per day for a week followed by 5 grams a day for 2 weeks increased DHT levels in male rugby players by about 40-to-60%.

That said, the study had several limitations (one being they didn’t actually measure hair loss, just a hormone often associated with it), and the results haven’t been replicated since. Thus, there’s very little evidence that creatine contributes to hair loss.

FAQ #12: Does caffeine make creatine less effective?

One study published in 1996 in the Journal of Applied Physiology suggested that taking creatine with caffeine “counteracts” some of its benefits.

Given that this study only included nine participants and that at least three subsequent studies have shown that the exact opposite is true—creatine and caffeine work synergistically—it’s probably safe to assume that caffeine doesn’t make creatine less effective.

FAQ #13: How much of a difference will creatine make in my training?

One review of around 300 studies published in Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry found that most people who supplement with creatine can expect a 5-to-15% increase in strength and power.

In another study conducted by scientists at Pennsylvania State University, researchers found that participants who supplemented with creatine could perform 30% more reps on the bench press across 5 sets of 10 reps.

That said, research also shows that 20-to-30% of people are creatine “non-responders” (they experience little or no benefit from taking creatine), which means not everyone will see improvements of this magnitude.

Scientific References +

- Cooper, R., Naclerio, F., Allgrove, J., & Jimenez, A. (2012). Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-9-33

- Wallimann, T., Tokarska-Schlattner, M., & Schlattner, U. (2011). The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine. Amino Acids, 40(5), 1271–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00726-011-0877-3

- Guzun, R., Timohhina, N., Tepp, K., Gonzalez-Granillo, M., Shevchuk, I., Chekulayev, V., Kuznetsov, A. V., Kaambre, T., & Saks, V. A. (2011). Systems bioenergetics of creatine kinase networks: physiological roles of creatine and phosphocreatine in regulation of cardiac cell function. Amino Acids, 40(5), 1333–1348. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00726-011-0854-X

- Schlattner, U., Tokarska-Schlattner, M., & Wallimann, T. (2006). Mitochondrial creatine kinase in human health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1762(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBADIS.2005.09.004

- Persky, A. M., Brazeau, G. A., & Hochhaus, G. (2003). Pharmacokinetics of the dietary supplement creatine. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 42(6), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200342060-00005

- Branch, J. D. (2003). Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.13.2.198

- Camic, C. L., Hendrix, C. R., Housh, T. J., Zuniga, J. M., Mielke, M., Johnson, G. O., Schmidt, R. J., & Housh, D. J. (2010). The effects of polyethylene glycosylated creatine supplementation on muscular strength and power. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3343–3351. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181FC5C5C

- Eckerson, J. M., Stout, J. R., Moore, G. A., Stone, N. J., Iwan, K. A., Gebauer, A. N., & Ginsberg, R. (2005). Effect of creatine phosphate supplementation on anaerobic working capacity and body weight after two and six days of loading in men and women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), 756–763. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16924.1

- Anomasiri, W., Sanguanrungsirikul, S., & Saichandee, P. (n.d.). Low dose creatine supplementation enhances sprint phase of 400 meters swimming performance - PubMed. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16083193/

- Safdar, A., Yardley, N. J., Snow, R., Melov, S., & Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2008). Global and targeted gene expression and protein content in skeletal muscle of young men following short-term creatine monohydrate supplementation. Physiological Genomics, 32(2), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1152/PHYSIOLGENOMICS.00157.2007

- Tang, F. C., Chan, C. C., & Kuo, P. L. (2014). Contribution of creatine to protein homeostasis in athletes after endurance and sprint running. European Journal of Nutrition, 53(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00394-013-0498-6

- Jäger, R., Harris, R. C., Purpura, M., & Francaux, M. (2007). Comparison of new forms of creatine in raising plasma creatine levels. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-4-17

- Qiang, F. (2015). Effect of Malate-oligosaccharide Solution on Antioxidant Capacity of Endurance Athletes. The Open Biomedical Engineering Journal, 9(1), 326. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874120701509010326

- Wu, J. L., Wu, Q. P., Huang, J. M., Chen, R., Cai, M., & Tan, J. B. (2007). Effects of L-malate on physical stamina and activities of enzymes related to the malate-aspartate shuttle in liver of mice. Physiological Research, 56(2), 213–220. https://doi.org/10.33549/PHYSIOLRES.930937

- Spillane, M., Schoch, R., Cooke, M., Harvey, T., Greenwood, M., Kreider, R., & Willoughby, D. S. (2009). The effects of creatine ethyl ester supplementation combined with heavy resistance training on body composition, muscle performance, and serum and muscle creatine levels. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-6-6

- Giese, M. W., & Lecher, C. S. (2009). Non-enzymatic cyclization of creatine ethyl ester to creatinine. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 388(2), 252–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BBRC.2009.07.151

- Astorino, T. A., Marrocco, A. C., Gross, S. M., Johnson, D. L., Brazil, C. M., Icenhower, M. E., & Kneessi, R. J. (2005). Is running performance enhanced with creatine serum ingestion? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), 730–734. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16744.1

- Gill, N. D., Hall, R. D., & Blazevich, A. J. (2004). Creatine serum is not as effective as creatine powder for improving cycle sprint performance in competitive male team-sport athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(2), 272–275. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-13193.1

- Harris, R. C., Almada, A. L., Harris, D. B., Dunnett, M., & Hespel, P. (2004). The creatine content of Creatine Serum and the change in the plasma concentration with ingestion of a single dose. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(9), 851–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410310001658739

- Bailey, S. J., Fulford, J., Vanhatalo, A., Winyard, P. G., Blackwell, J. R., DiMenna, F. J., Wilkerson, D. P., Benjamin, N., & Jones, A. M. (2010). Dietary nitrate supplementation enhances muscle contractile efficiency during knee-extensor exercise in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 109(1), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00046.2010

- Galvan, E., Walker, D. K., Simbo, S. Y., Dalton, R., Levers, K., O’Connor, A., Goodenough, C., Barringer, N. D., Greenwood, M., Rasmussen, C., Smith, S. B., Riechman, S. E., Fluckey, J. D., Murano, P. S., Earnest, C. P., & Kreider, R. B. (2016). Acute and chronic safety and efficacy of dose dependent creatine nitrate supplementation and exercise performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-016-0124-0

- Brilla, L. R., Giroux, M. S., Taylor, A., & Knutzen, K. M. (2003). Magnesium-creatine supplementation effects on body water. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 52(9), 1136–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(03)00188-4

- Selsby, J. T., DiSilvestro, R. A., & Devor, S. T. (2004). Mg2+-creatine chelate and a low-dose creatine supplementation regimen improve exercise performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(2), 311–315. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-13072.1

- Jagim, A. R., Oliver, J. M., Sanchez, A., Galvan, E., Fluckey, J., Riechman, S., Greenwood, M., Kelly, K., Meininger, C., Rasmussen, C., & Kreider, R. B. (2012). A buffered form of creatine does not promote greater changes in muscle creatine content, body composition, or training adaptations than creatine monohydrate. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-9-43

- Jäger, R., Harris, R. C., Purpura, M., & Francaux, M. (2007). Comparison of new forms of creatine in raising plasma creatine levels. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-4-17

- Kreider, R. B., Kalman, D. S., Antonio, J., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Wildman, R., Collins, R., Candow, D. G., Kleiner, S. M., Almada, A. L., & Lopez, H. L. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2017 14:1, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-017-0173-Z

- Rawson, E. S., & Volek, J. S. (n.d.). Effects of creatine supplementation and resistance training on muscle strength and weightlifting performance - PubMed. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14636102/

- Efficacy of Alternative Forms of Creatine Supplementation on... : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/9000/Efficacy_of_Alternative_Forms_of_Creatine.94079.aspx

- Groeneveld, G. J., Beijer, C., Veldink, J. H., Kalmijn, S., Wokke, J. H. J., & Van Den Berg, L. H. (2005). Few adverse effects of long-term creatine supplementation in a placebo-controlled trial. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2004-817917

- Candow, D. G., Vogt, E., Johannsmeyer, S., Forbes, S. C., & Farthing, J. P. (2015). Strategic creatine supplementation and resistance training in healthy older adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition et Metabolisme, 40(7), 689–694. https://doi.org/10.1139/APNM-2014-0498

- McMorris, T., Mielcarz, G., Harris, R. C., Swain, J. P., & Howard, A. (2007). Creatine supplementation and cognitive performance in elderly individuals. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition. Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 14(5), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825580600788100

- Cooper, R., Naclerio, F., Allgrove, J., & Jimenez, A. (2012). Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-9-33

- Bemben, M. G., & Lamont, H. S. (2005). Creatine supplementation and exercise performance: recent findings. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 35(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200535020-00002

- Pline, K. A., & Smith, C. L. (2005). The effect of creatine intake on renal function. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 39(6), 1093–1096. https://doi.org/10.1345/APH.1E628

- Gualano, B., Ferreira, D. C., Sapienza, M. T., Seguro, A. C., & Lancha, A. H. (2010). Effect of short-term high-dose creatine supplementation on measured GFR in a young man with a single kidney. American Journal of Kidney Diseases : The Official Journal of the National Kidney Foundation, 55(3). https://doi.org/10.1053/J.AJKD.2009.10.053

- Banfi, G., & Del Fabbro, M. (2006). Serum creatinine values in elite athletes competing in 8 different sports: comparison with sedentary people. Clinical Chemistry, 52(2), 330–331. https://doi.org/10.1373/CLINCHEM.2005.061390

- Rockwell, J. A., Walberg Rankin, J., & Toderico, B. (2001). Creatine supplementation affects muscle creatine during energy restriction. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200101000-00011

- Van Der Merwe, J., Brooks, N. E., & Myburgh, K. H. (2009). Three weeks of creatine monohydrate supplementation affects dihydrotestosterone to testosterone ratio in college-aged rugby players. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine : Official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 19(5), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0B013E3181B8B52F

- Vandenberghe, K., Gillis, N., Van Leemputte, M., Van Hecke, P., Vanstapel, F., & Hespel, P. (1996). Caffeine counteracts the ergogenic action of muscle creatine loading. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 80(2), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPL.1996.80.2.452

- Lee, C. L., Lin, J. C., & Cheng, C. F. (2011). Effect of caffeine ingestion after creatine supplementation on intermittent high-intensity sprint performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 111(8), 1669–1677. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-010-1792-0

- Doherty, M., Smith, P. M., Davison, R. C. R., & Hughes, M. G. (2002). Caffeine is ergogenic after supplementation of oral creatine monohydrate. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34(11), 1785–1792. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200211000-00015

- Lee, C. L., Lin, J. C., & Cheng, C. F. (2012). Effect of creatine plus caffeine supplements on time to exhaustion during an incremental maximum exercise. European Journal of Sport Science, 12(4), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2011.573578

- Kreider, R. B. (n.d.). Effects of creatine supplementation on performance and training adaptations - PubMed. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12701815/

- Volek, J. S., Kraemer, W. J., Bush, J. A., Boetes, M., Incledon, T., Clark, K. L., & Lynch, J. M. (1997). Creatine supplementation enhances muscular performance during high-intensity resistance exercise. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 97(7), 765–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00189-2

- Syrotuik, D. G., & Bell, G. J. (2004). Acute creatine monohydrate supplementation: a descriptive physiological profile of responders vs. nonresponders. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(3), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1519/12392.1