When was the last time you did a dumbbell split squat?

If you’re unfamiliar with this exercise (or not doing it regularly), you may be missing out.

It’s so effective because it allows you to train your entire lower body one leg at a time. This helps you build balanced size and strength and potentially enhances athletic performance.

Moreover, you can perform it almost anywhere using whatever equipment you have available, making it a highly adaptable lower-body exercise you can perform wherever and however you like.

In this article, you’ll learn what the split squat is, why it’s beneficial, which muscles it works, how to perform it with proper form, avoid common mistakes, and include it in your program, the best alternatives, and more.

What Is A Split Squat?

The dumbbell split squat is a lower-body exercise.

To perform this exercise, grab a dumbbell (or kettlebell) in each hand and step forward with one foot. Bend both knees, lowering your body until the knee of your rear leg brushes the floor, then stand back up.

Split Squat: Benefits

1. It trains your entire lower body.

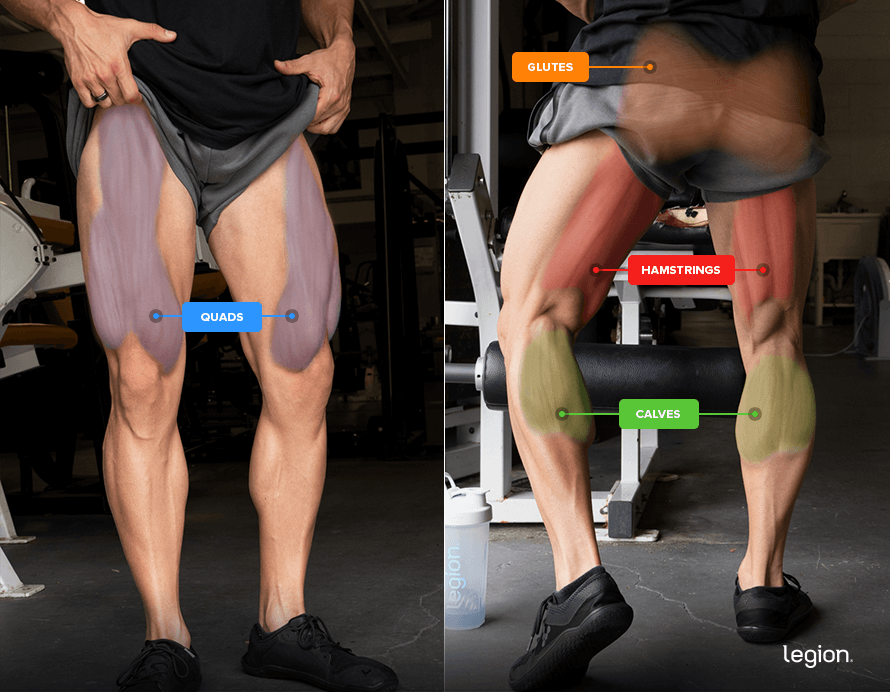

The split squat trains your entire lower body, including your quads, hamstrings, glutes, and calves.

It also mimics movements we make in everyday life (e.g., climbing stairs, stepping over objects, and running). Hence, the split squat can help make daily activities easier by strengthening the muscles involved in these movements.

2. It trains your lower body unilaterally.

The split squat is a unilateral exercise, which means it allows you to train one side of your body at a time.

This is beneficial because unilateral exercises . . .

- May allow you to lift more total weight than some bilateral exercises (exercises that train both sides of the body at the same time), potentially helping you gain more muscle over time

- Help you develop a greater mind-muscle connection with your quads, glutes, and hamstrings because you only need to focus on a single leg at a time

- Help you correct muscle imbalances because both sides of your body are forced to lift the same amount of weight (one side can’t “take over” from the other)

- Improve several aspects of your athletic performance more than bilateral exercises, including jumping, agility, and speed

3. It’s highly adaptable.

The split squat doesn’t require a squat rack, machine, or bench, so you can perform it virtually anywhere, whether at the gym, at home, or in a hotel room while traveling.

Additionally, you can add resistance to the split squat using any equipment you have available, including dumbbells, kettlebells, a barbell, or resistance bands. And if you have none of these to hand, you can use just your body weight.

In other words, the split squat is an adaptable exercise for training your lower body, wherever and however you choose to exercise.

Split Squat: Muscles Worked

- Quadriceps

- Hamstrings

- Glutes

- Calves

Here’s how these muscles look on your body:

How to Do Split Squats

The best way to learn how to do a split squat with proper form is to split the exercise into three parts: set up, descend, and squat.

1. Set up

Hold a dumbbell in each hand and let your arms hang at your sides. Stand upright with your feet hip-width apart, your chest up, and your shoulders back, then step 2-to-3 feet forward with your right foot.

2. Descend

Lower your body by bending both knees until your left knee touches the floor and your right thigh is parallel to the floor. As you descend, keep your upper body upright and allow the heel on your left foot to come off the floor.

3. Squat

Reverse the motion by pushing through your front heel to straighten your legs and return to the start position. Once you’ve performed the desired number of reps, switch legs and repeat the process.

Here’s how it should look when you put it all together:

Split Squat: Common Mistakes

1. Taking an overly narrow stance.

Having your feet almost in line with each other can make balancing more difficult. Avoid this by ensuring your feet stay about hip-width apart throughout the exercise.

2. Bouncing your knee off the floor.

Descending too quickly can cause you to bounce your knee off the floor.

While it might make the exercise feel easier, it can increase injury risk and prevent your legs from working as hard, robbing you of muscle and strength gain.

3. Stepping too far forward.

Taking an overly long stride during the set-up can make the split squat uncomfortable and balancing more challenging.

To avoid this, only step 2-to-3 feet forward when setting up.

How to Include the Split Squat in Your Program

Include the split squat toward the end of your lower-body or leg workouts after your main bilateral exercises. Here’s an example of how you might do this:

- Barbell Back Squat: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Romanian Deadlift: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Split Squat: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Leg Curl: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

If you like the look of this workout and want a strength training program for your entire body, check out my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger.

The Best Split Squat Alternatives

1. Barbell Split Squat

Using a barbell instead of dumbbells for the split squat allows you to lift heavy weights because you aren’t limited by your grip strength, which is generally better for gaining muscle and strength.

The downsides are that it’s not as easy to drop the weight if you lose balance, and it places the load on your back, which may not be suitable for those with back issues.

2. Bulgarian Split Squat

The only difference between the Bulgarian and regular split squats is that the former involves raising your rear foot on a bench or box.

Elevating your rear leg places more weight on your front foot, which means the Bulgarian split squat works your muscles slightly more.

That said, the split squat demands less coordination and balance, making it a more suitable choice for beginner weightlifters or those recovering from injuries.

3. ATG Split Squat

The ATG split squat is essentially a regular split squat performed through a longer range of motion.

In the ATG (“ass-to-grass”) split squat, you lower your body as far as possible and push your front knee over the top of your foot, causing your front leg’s hamstring and calf to meet. Some experts believe this makes the ATG split squat highly effective for gaining quad strength, improving flexibility, and developing injury-resistant knees.

Bear in mind the ATG version requires a degree of flexibility many lack. If this is the case for you, a good workaround is to elevate your front leg and place a wedge under your foot.

Scientific References +

- Schellenberg, Florian, et al. “Towards Evidence Based Strength Training: A Comparison of Muscle Forces during Deadlifts, Goodmornings and Split Squats.” BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, vol. 9, no. 1, 17 July 2017, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-017-0077-x.

- Jakobi, Jennifer M., and Philip D. Chilibeck. “Bilateral and Unilateral Contractions: Possible Differences in Maximal Voluntary Force.” Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 26, no. 1, Feb. 2001, pp. 12–33, https://doi.org/10.1139/h01-002. Accessed 1 Jan. 2020.

- Janzen, Cora L., et al. “The Effect of Unilateral and Bilateral Strength Training on the Bilateral Deficit and Lean Tissue Mass in Post-Menopausal Women.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 97, no. 3, 28 Mar. 2006, pp. 253–260, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-006-0165-1. Accessed 26 Jan. 2022.

- Kai-Fang, Liao, et al. Effects of Unilateral vs. Bilateral Resistance Training Interventions on Measures of Strength, Jump, Linear and Change of Direction Speed: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mar. 2022, www.termedia.pl/Effects-of-unilateral-vs-bilateral-resistance-training-interventions-on-measures-of-strength-jump-linear-and-change-of-direction-speed-a-systematic-review-and-meta-analysis,78,44423,0,1.html. Accessed Mar. 2022.

- Krause, David A, et al. “ELECTROMYOGRAPHY of the HIP and THIGH MUSCLES during TWO VARIATIONS of the LUNGE EXERCISE: A CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 13, no. 2, 2018, pp. 137–142, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6063068/. Accessed 3 Sept. 2022.