Many people think veganism and bodybuilding are mutually exclusive.

You know, like oil and water . . . toothpaste and coffee . . . Apple and Microsoft . . . anathema.

Well, they’re wrong. You absolutely can do both. But you have to know what you’re doing.

That’s because vegan bodybuilding diets are easier to mess up than the traditional omnivorous approach, and if you don’t understand and address the downsides and limitations of the vegan diet in the context of bodybuilding, you’ll get disappointing results.

If you do, though, and plan and adjust accordingly, then you’ll have no problem building muscle, losing fat, and getting strong.

And that’s what this article is all about.

In it, you’re going to learn . . .

- What a vegan bodybuilding diet is

- How to make a vegan bodybuilding diet work (including how to set up your vegan macros, how to get protein as a vegan, and which supplements to include in your vegan bodybuilding meal plan)

- Whether or not you should avoid soy protein

- How to plan vegan bodybuilding meals (with some examples)

What Is a Vegan Bodybuilding Diet?

The aim of any bodybuilding diet is to feed the body the nutrients it needs to maximize muscle growth and minimize fat gain. Since protein is the most important macronutrient for muscle growth, bodybuilding diets tend to include lots of high-protein foods, such as meat, fish, eggs, and dairy.

A vegan bodybuilding diet is very similar, only instead of containing a lot of high-protein foods from animal sources, it contains a lot of high-protein foods from plant sources.

How to Make a Vegan Bodybuilding Diet Work for You

The main reasons people fail to make a vegan bodybuilding diet work are . . .

- They don’t know how to set up their vegan macros

- They don’t know how to get protein as a vegan

- They don’t know which supplements to take

Follow these five science-based tips, though, and you’ll avoid all the pitfalls associated with building muscle as a vegan.

1. Determine your daily calories.

There are many different ways to figure this out, but the easiest way is to enter your stats and goal in the Legion Calorie Calculator.

All you have to do is enter your gender, weight, height, age, activity level, and goal (“Lose fat,” “Build lean muscle,” or “Maintain the same weight”), and the calculator will estimate . . .

- Your basal metabolic rate (BMR)

- Your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE)

- How many calories you should consume each day to reach your goal

These numbers are based on the fact that . . .

- If you want to lose weight, you should eat 75-to-80% of your TDEE, or 20-to-25% less energy than you’re burning every day.

- If you want to gain weight, you should eat 110-to-115% of your TDEE, or 10-to-15% more energy than you’re burning.

- And if you want to maintain your weight, you should eat 100% of your TDEE, or more or less exactly what you’re burning every day.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

2. Eat a high-protein diet.

Dozens of well-designed, peer–reviewed studies have shown beyond a shadow of a doubt that a high-protein diet is superior for building (or maintaining) muscle and losing fat than a low-protein one.

Unfortunately, this is where many vegans die on the vine, because despite what vegans often preach, veggies aren’t a great source of protein.

Not only that, but the protein found in plants isn’t absorbed by the body as well as protein from animal sources.

This double whammy is one of the main reasons vegan protein sources aren’t as effective for building muscle as animal protein sources.

One way to help bridge the gap is to eat more protein on a vegan bodybuilding diet than you would if you were following an omnivorous bodybuilding diet.

Specifically, aim to eat at least 1-to-1.2 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day.

3. Eat high-leucine foods.

Getting enough total protein is only one piece of the vegan-protein puzzle—you also have to eat foods that are high in the essential amino acid leucine.

Leucine directly stimulates protein synthesis via the activation of an enzyme responsible for muscle growth known as the mammalian target of rapamycin, or mTOR.

This is why research shows that the leucine content of a meal directly affects the amount of protein synthesis that occurs as a result.

In other words, high-leucine meals have a higher muscle-building potential than low-leucine meals.

This is the other major reason vegan protein sources are inferior to animal protein sources for building muscle: they tend to be low in leucine and other essential amino acids.

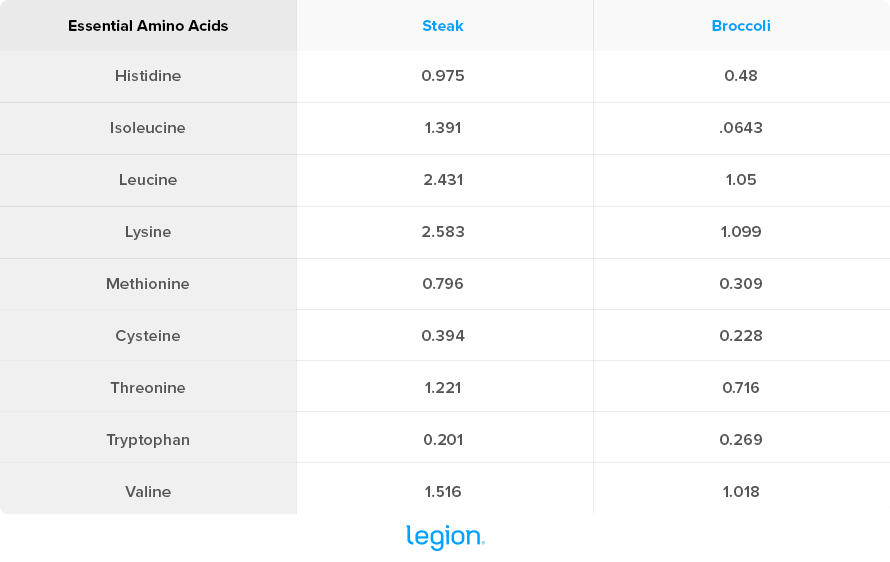

To illustrate this point, let’s compare the protein found in broccoli to the protein found in beef.

Here’s what 275 calories of each (4 ounces of steak vs. just over 9 cups of broccoli) will get you in terms of essential amino acids:

The best solution to this problem is to eat plenty of vegan foods that are both high in easily-absorbed protein, and high in leucine, such as . . .

The Best Protein Sources for a Vegan Bodybuilding Diet:

- Plant-based protein powder

- Vital wheat gluten

- Oats

- Soy beans

- Lentils

- Navy beans

- Kidney beans

- Peanuts

- Black beans

- Mung beans

4. Eat enough fat and make up your calories with carbs.

Setting up your vegan macros for building muscle isn’t just about protein—you have to eat enough fat and carbs, too.

That’s because . . .

- Dietary fat is an essential nutrient and part of many physiological processes ranging from hormone production to insulin sensitivity, cell turnover, satiety, muscle growth, and nutrient absorption.

- Carbs are the primary fuel source for intense exercise and can help you gain muscle and strength faster by keeping glycogen levels topped off. They also don’t get in the way of fat loss, and serve as a great source of various micronutrients and fiber.

Here’s how to make sure you get enough of both:

Fat: Eat around 0.3 grams of fat per pound of body weight per day. That’s enough to support general health and well-being, but not so much that you have to reduce protein and carbohydrate intake unnecessarily to stay within your calorie limits.

Some of the best fat sources for a vegan bodybuilding diet are:

- Avocado

- Walnuts

- Peanuts or peanut butter

- Almonds or almond butter

- Pistachios

- Cashews

- Tahini

- Olive oil

- Sunflower seeds

- Pumpkin seeds

Carbs: Allot any calories you haven’t used on protein or fat to carbs.

Once you know that a gram of protein and carbohydrate both contain about 4 calories, and a gram of fat contains about 9, figuring out your carbs is pretty easy. All you have to do is . . .

- Multiply your protein target by 4.

- Multiply your fat target by 9.

- Add these together and subtract the sum from your total calories (the number you got from the Legion Calorie Calculator earlier), giving you the number of calories you have remaining for carbs.

- Divide this remaining number by 4 to get the number of grams of carbs you should eat every day.

Let’s look at an example of how this plays out.

I weigh about 190 pounds and my TDEE is about 2,700 calories, which is roughly what I eat every day to maintain my weight and body composition.

I need to eat about 190 grams of protein and 60 grams of fat per day, and here’s how I figure out my carbs:

190 x 4 = 760

60 x 9 = 540

760 + 540 = 1,300

2,700 – 1,300 = 1,400 calories remaining for carbs.

1,400 / 4 = 350 grams of carbs per day.

Thus, my macros are:

- 190 grams of protein

- 60 grams of fat

- 350 grams of carbs

Some of the best carb sources for a vegan bodybuilding diet are:

- Potatoes (sweet and white)

- Oats

- Rice (brown, white, wild)

- Bulgur

- Quinoa

- Spelt

- Amaranth

- Whole-wheat pasta and bread

- Vegetables like broccoli, carrots, kale, mushrooms, and cauliflower

- Fruit like bananas, apples, berries, pineapple, and oranges

(And again, if you feel confused about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz to learn exactly what diet is right for you.)

5. Take the right supplements.

It’s not uncommon for people who follow a vegan diet to be deficient in some vitamins and minerals such as . . .

- Vitamin B12

- Vitamin D

- Calcium

- Riboflavin (B2)

- Iodine

- Iron

- Zinc

- Essential fatty acids

- Creatine

- Anserine

- Taurine

- Carnosine

You’ve probably also heard that these common deficiencies among vegans can be avoided by simply adding certain foods to your diet.

This is true to a point, but it’s also easier said than done.

For example, the calcium in some vegetables isn’t as bioavailable as the calcium in dairy products (and in any case, multiple servings of veggies are needed to equal a single serving of dairy).

Many plant sources of iron and zinc are also inferior to animal sources and must be consumed in large amounts.

Omega-3 fatty acids are primarily found in animal products, and the main vegan source of this vital kind of fat is alpha-linolenic acid, which is poorly absorbed by the body.

All this means that you have two options if you want to optimize your health and performance on a vegan diet:

- Micromanage your diet to include generous amounts of foods high in the nutrients listed above.

- Supplement.

Personally, I would choose door number two because it’s easy and fairly inexpensive, but if you’re a staunch anti-supplement guy or gal, you’ll need to put extra time into your meal planning to ensure you’re getting adequate amounts of the many vital nutrients your body needs.

Here are some of my recommended sources for hard-to-get nutrients on a vegan diet:

- Vitamin B12: supplement, fortified cereals.

- Vitamin D: supplement.

- Calcium: edamame, tofu, sesame seeds, almonds, spinach, and bok choy.

- Riboflavin: almonds, mushrooms, fortified cereals.

- Iodine: seaweed (especially Kombu kelp), iodized salt.

- Iron: beans, prunes, fortified cereals.

- Zinc: soy products, nuts, seeds, mushrooms, and lentils.

- Essential fatty acids: ground flaxseeds and walnuts, but I’d recommend an algae oil instead (though this can be expensive).

- Creatine: supplement

- Anserine: supplement

- Taurine: supplement

- Carnosine: supplement

The other supplement that’s definitely worth inclusion in your vegan bodybuilding diet plan is plant-based protein powder.

Nowadays, there are a zillion different plant-based protein powders on the market, with some of the most popular options being soy, hemp, pea, rice, and quinoa protein powder.

Instead of going into the pros and cons of each, I’ll cut to the chase: the best plant-based protein powder for building muscle is a blend of rice and pea.

Not only are rice and pea blends easily digested, they contain high amounts of the essential amino acids leucine, isoleucine, and valine which make them particularly good for building muscle.

Thus, it’s not surprising that research shows a mix of pea and rice protein is about as effective as whey protein for building muscle.

If you want a high-protein, all-natural, and nutritionally enhanced plant protein powder that’s also delicious to drink, check out Legion’s 100% natural plant-based protein powder, Plant+.

A Quick Word on Soy Protein

Soy protein is a mixed bag.

It’s an all-round good source of protein for building muscle, but it’s also a source of ongoing controversy.

Some studies show that regular intake of soy foods has feminizing effects in men . . . Other research shows that it does nothing to alter male hormone levels . . . And yet other studies show it helps normalize estrogen levels by either suppressing or increasing production as needed.

Thus, it’s difficult to say for certain whether or not soy-based products are a good addition to your vegan bodybuilding meal plan.

What we do know, though, is the effects can vary depending on the presence or absence of certain intestinal bacteria. These bacteria, which are present in 30-to-50% of people, metabolize an isoflavone in soy called daidzein into an estrogen-like hormone called equol which causes testosterone levels to drop, and estrogen levels to rise . . . at least in men.

For women, research suggests it’s less likely to negatively affect hormones, regardless of equol production, so there’s no reason for concern here.

All things considered, I’d say completely avoiding soy protein is probably unnecessary.

That said, why not opt for something else when there are so many other sources of plant-based protein available?

If you want to learn more about the best sources of protein for vegan muscle building, check out this article:

30 of the Best Sources of Vegan Protein for Building Muscle

Example Vegan Bodybuilding Meal Plan

At this point you’d probably like to see some well-planned vegan bodybuilding meals, so here are a few that we’ve made for our custom meal plan clients.

As you can see, with a little work and creativity, you can hit your macros while avoiding all animal products.

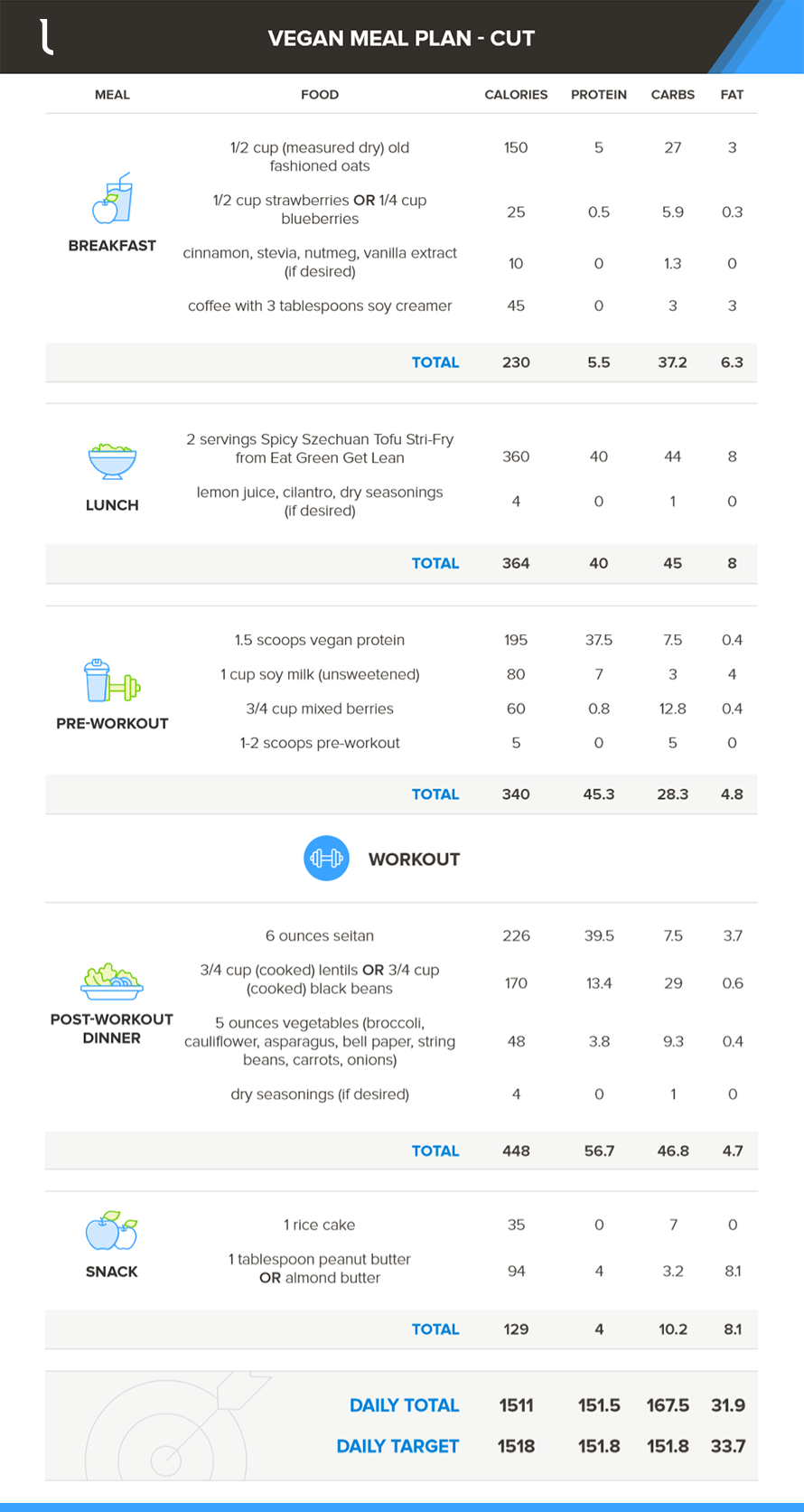

Here’s an example of a vegan bodybuilding cutting diet:

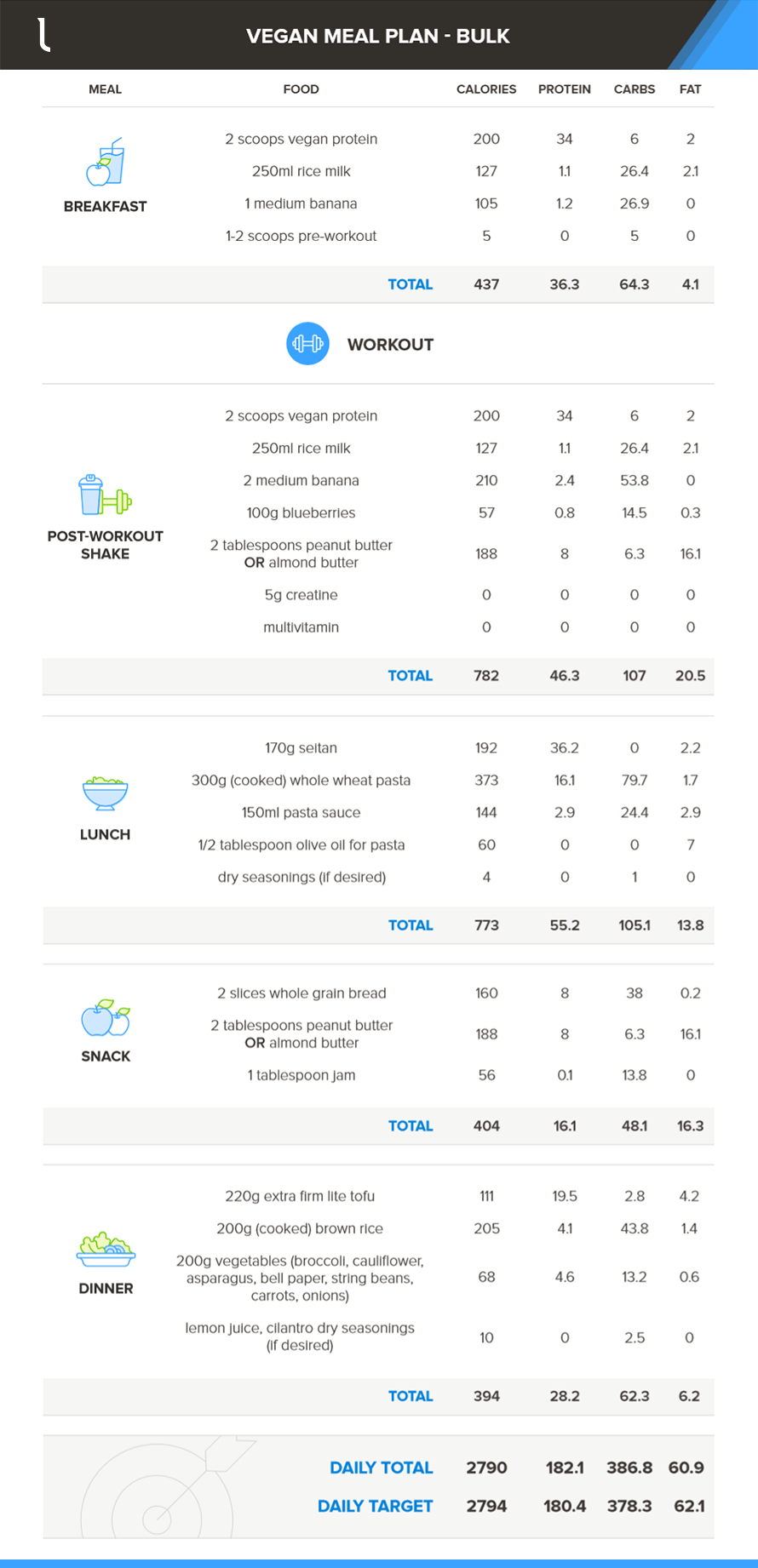

And here’s an example of a vegan bodybuilding diet plan for bulking:

Scientific References +

- MS, K. (2002). Hormonal effects of soy in premenopausal women and men. The Journal of Nutrition, 132(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/132.3.570S

- Liu, B., Qin, L., Liu, A., Uchiyama, S., Ueno, T., Li, X., & Wang, P. (2010). Prevalence of the equol-producer phenotype and its relationship with dietary isoflavone and serum lipids in healthy Chinese adults. Journal of Epidemiology, 20(5), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.2188/JEA.JE20090185

- CL, F., C, A., WK, T., A, G., T, J., K, W., SM, S., SS, L., & JW, L. (2005). High concordance of daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes in individuals measured 1 to 3 years apart. The British Journal of Nutrition, 94(6), 873–876. https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN20051565

- CS, H., HS, K., HJ, L., SH, L., YS, K., TB, C., HG, H., & KO, H. (2006). Isoflavone metabolites and their in vitro dual functions: they can act as an estrogenic agonist or antagonist depending on the estrogen concentration. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 101(4–5), 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSBMB.2006.06.020

- JM, H.-R., G, V., SJ, D., WR, P., MS, K., & MJ, M. (2010). Clinical studies show no effects of soy protein or isoflavones on reproductive hormones in men: results of a meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility, 94(3), 997–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FERTNSTERT.2009.04.038

- M, M. (2010). Soybean isoflavone exposure does not have feminizing effects on men: a critical examination of the clinical evidence. Fertility and Sterility, 93(7), 2095–2104. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FERTNSTERT.2010.03.002

- JE, C., TL, T., SM, S., & R, H. (2008). Soy food and isoflavone intake in relation to semen quality parameters among men from an infertility clinic. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 23(11), 2584–2590. https://doi.org/10.1093/HUMREP/DEN243

- JE, T., DR, M., GW, K., MA, T., & SM, P. (2009). Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 107(3), 987–992. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00076.2009

- JM, J., RP, L., JM, W., M, P., EO, D. S., SM, W., DS, K., JE, D., & R, J. (2013). The effects of 8 weeks of whey or rice protein supplementation on body composition and exercise performance. Nutrition Journal, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-86

- Babault, N., Païzis, C., Deley, G., Guérin-Deremaux, L., Saniez, M.-H., Lefranc-Millot, C., & Allaert, F. A. (2015). Pea proteins oral supplementation promotes muscle thickness gains during resistance training: a double-blind, randomized, Placebo-controlled clinical trial vs. Whey protein. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2015 12:1, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-014-0064-5

- Okuda, M., & Wang, D. (n.d.). Rice Protein - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved July 7, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/rice-protein

- F, M., ME, P., D, T., S, B., R, B., & S, M. (2001). The influence of the albumin fraction on the bioavailability and postprandial utilization of pea protein given selectively to humans. The Journal of Nutrition, 131(6), 1706–1713. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/131.6.1706

- JR, H. (2003). Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(3 Suppl). https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/78.3.633S

- Weaver, C. M., Proulx, W. R., & Heaney, R. (1999). Choices for achieving adequate dietary calcium with a vegetarian diet. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(3), 543s-548s. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/70.3.543S

- Pasantes, H., Quesada, O., Olea, R. S., & Alcocer, L. (n.d.). (PDF) Taurine content in foods. Retrieved July 7, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279550569_Taurine_content_in_foods

- Y, H., W, H., S, H., & G, W. (2019). Composition of polyamines and amino acids in plant-source foods for human consumption. Amino Acids, 51(8), 1153–1165. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00726-019-02751-0

- DG, B., PD, C., G, P., DG, C., D, M., & M, T. (2003). Effect of creatine and weight training on muscle creatine and performance in vegetarians. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(11), 1946–1955. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000093614.17517.79

- MS, R., Z, L.-W., PN, A., TA, S., NE, A., & TJ, K. (2005). Long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in plasma in British meat-eating, vegetarian, and vegan men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 82(2), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN.82.2.327

- M, F., & S, S. (2015). Vegetarian diets across the lifecycle: impact on zinc intake and status. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, 74, 93–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.AFNR.2014.11.003

- R, H., & I, E. (2010). Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(5). https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.2010.28674F

- AM, L., A, L., X, H., LE, B., & EN, P. (2011). Iodine status and thyroid function of Boston-area vegetarians and vegans. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 96(8). https://doi.org/10.1210/JC.2011-0256

- Rogerson, D. (2017). Vegan diets: practical advice for athletes and exercisers. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12970-017-0192-9

- WJ, C. (2010). Nutrition concerns and health effects of vegetarian diets. Nutrition in Clinical Practice : Official Publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 25(6), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533610385707

- E, S., & E, N. (1991). Effect of the cobalt-N coordination on the cobamide recognition by the human vitamin B12 binding proteins intrinsic factor, transcobalamin and haptocorrin. European Journal of Biochemistry, 199(2), 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1432-1033.1991.TB16124.X

- KR, H., SM, P., MJ, M., D, R., NA, M., & MJ, G. (2010). Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 109(2), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00108.2009

- LM, B., B, K., & JL, I. (2004). Carbohydrates and fat for training and recovery. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264041031000140527

- Berrazaga, I., Micard, V., Gueugneau, M., & Walrand, S. (2019). The Role of the Anabolic Properties of Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Sources in Supporting Muscle Mass Maintenance: A Critical Review. Nutrients, 11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU11081825

- LE, N., DK, L., P, B., TG, A., DV, B., & PJ, G. (2009). The leucine content of a complete meal directs peak activation but not duration of skeletal muscle protein synthesis and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in rats. The Journal of Nutrition, 139(6), 1103–1109. https://doi.org/10.3945/JN.108.103853

- SR, K., & LS, J. (2006). Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(1 Suppl). https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/136.1.227S

- S, van V., NA, B., & LJ, van L. (2015). The Skeletal Muscle Anabolic Response to Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Consumption. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(9), 1981–1991. https://doi.org/10.3945/JN.114.204305

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2014 11:1, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- SM, P., & LJ, V. L. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29 Suppl 1(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.619204

- S, M., N, M., & KD, T. (2010). Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(2), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0B013E3181B2EF8E