Getting started with weightlifting can be overwhelming.

Choosing which exercises to do, learning how to do them correctly, knowing when and how to add weight or reps, deciding how many sets to do and how many days per week to train . . . it all seems about as straightforward as computing calculus with an abacus.

In reality, though, weightlifting is one of the simplest sports to master, requiring far less know-how and technical proficiency than most.

In this article, you’ll learn everything you need to know to get going in the gym, the best beginner weightlifting program, and more.

What Is Weightlifting?

Weightlifting, also known as weight training, strength training, or resistance training, is a type of physical exercise that involves performing movements against resistance to gain muscle and strength.

Often, the “tools” you use to create resistance are barbells, dumbbells, and kettlebells (collectively known as free weights), though you can also use weightlifting machines, resistance bands, and your body weight.

The Benefits of Weightlifting

1. It builds muscle.

As you probably know, weightlifting helps you build muscle. What you might not realize, however, is how quickly you gain muscle when you start lifting weights.

For example, in one study conducted by scientists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 38 greenhorn weightlifters who trained 4 days per week for 12 weeks gained up to ~12 lb of muscle (while losing fat!).

Having muscle is important because it makes performing everyday tasks easier, protects you against injury, boosts your athletic performance, extends your life expectancy, and helps you maintain good metabolic health, reducing your risk of numerous metabolic diseases that can negatively affect your body composition and health.

2. It burns fat.

Several studies show that lifting weights increases your resting metabolic rate (RMR—the number of calories you burn at rest), making it a great way to support long-term weight loss.

The main reason for this is that muscle mass burns more calories at rest than fat, so your body burns more calories even when you aren’t training.

Furthermore, when we lift weights, our muscles release special fluid-filled particles into our blood called extracellular vesicles. As these special particles leave our muscles, they carry strands of genetic material called miR-1, which they then deposit in neighboring fat cells.

Importantly, when miR-1 is in muscle tissue, it hinders muscle growth, but once it’s deposited in fat cells, it hastens fat burning. In other words, lifting weights causes subtle shifts in the expression of certain genes that accelerate muscle growth and fat burning.

3. It boosts health.

Weightlifting boosts your health in myriad ways, including improving your body composition, blood pressure, blood glucose level and insulin sensitivity, mobility and physical function, blood lipid profile, bone mineral density and bone health, cognition, and immune function.

It also lowers your risk of countless diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

4. It improves sleep.

Getting sufficient sleep (7-to-9 hours per night for most people) is paramount for maintaining good health and well-being.

Despite this, around one-third of Americans don’t sleep enough, 5-to-15% suffer from insomnia, and one-third report waking at least three times per night.

Sleep disturbances like these reduce sleep quality and increase your risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, depression and anxiety, and death from all causes. They also make you more likely to lose focus and be less productive during the day, and increase your risk of being involved in potentially life-threatening accidents.

Studies show that lifting weights increases the quality and quantity of your sleep and how well you function during the day.

5. It improves your quality of life.

Studies show that weightlifting increases your self-efficacy, self-esteem, and self-worth, reduces anxiety, boosts mood, and helps you stay independent as you age, which collectively improve your mental well-being and quality of life.

Getting Started with Weightlifting

Before you start weightlifting, it pays to have a plan that optimizes your time in the gym and ensures you stay safe.

Let’s go over the main things you need to know.

How Often Should You Train?

It’s common to see fit people bragging about how much time they spend training each week (#nodaysoff).

While training hard is commendable, training intensely for 6 or 7 days per week is a good way to burn out, physically and psychologically.

The best way to avoid this is to train enough to spur progress but not so much that you risk your health or well-being.

A good starting place for most people is training 3 days per week, preferably on non-consecutive days. For example, you could train on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and take the other days of the week off lifting.

The only caveat is that as you become more experienced, you may need to increase your training frequency (the number of workouts you do per week) to continue progressing. This isn’t necessary in the beginning, though, so stick with 3 days per week until progress stalls.

You can train more often than this if you want to, but it’s usually not necessary.

How Many Sets Should You Do Per Workout?

A set is a number of repetitions (reps) of an exercise performed back-to-back without rest.

For example, if a workout calls for 3 sets of 10 reps of bench press, you’d unrack the bar, do 10 reps (1 set), re-rack the bar, rest, and then continue like this until you finish all 3 sets.

Beginner weightlifters only need to do ~10-to-12 weekly sets per major muscle group to make excellent progress.

How Many Reps Should You Do Per Set?

Despite what some “experts” say, you don’t need to do 20+ reps per set to build muscle.

While it’s possible to build muscle using high rep ranges, research shows that they’re only effective if you take each set to failure (the point at which you can’t complete a rep despite giving maximum effort).

There are two problems with this training style: doing high-rep sets is extremely unpleasant (sets take longer, feel harder, and cause more fatigue than lower-rep sets) and training to failure regularly can increase your risk of injury.

By increasing the weight and doing fewer reps per set, however, you can produce a powerful muscle-building stimulus without busting a gut or training to failure.

That’s why I recommend you do the bulk of your training in the 6-to-10 rep range, which means lifting weights between 70-to-80% of your one rep max (the most weight you can lift on an exercise for one rep).

As you become more accustomed to weightlifting, working in even lower rep ranges (4-to-6, for example) may help you gain strength even more effectively, but this isn’t necessary while starting out.

What Type of Exercises Should You Do?

There are two types of weightlifting exercises: compound exercises and isolation exercises.

A compound exercise involves multiple joints and muscles. For example, the squat involves moving the knees, ankles, and hips and requires a whole-body coordinated effort, with the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes bearing the brunt of the load.

An isolation exercise involves just one joint and muscle. For example, the biceps curl involves moving the elbow and trains the biceps only.

Compound exercises should make up the lion’s share of any well-designed weightlifting program. The main reason for this is that compound exercises allow you to train dozens of muscles simultaneously, allowing you to lift more weight safely, which is generally better for muscle and strength gain.

Additionally, they allow you to train more efficiently (one compound exercise can do the work of several isolation exercises) and raise testosterone and growth hormone levels more than isolation exercises.

While hormonal changes like these don’t influence muscle gain as much as some people would have you believe, they’re beneficial nonetheless.

This doesn’t mean you should avoid isolation exercises altogether, though.

A good rule of thumb is to spend about 80% of your time in the gym doing compound exercises and the remaining 20% doing isolation exercises.

How Do You Use Proper Form?

To use proper form, you need to control how your body and the weight are moving in each rep. You should always feel like you’re using your muscles to execute the movements, not gravity or momentum.

For example, when doing the dumbbell bench press, instead of relaxing your pecs and arms and allowing the dumbbells to drop toward your chest, you should keep your upper-body muscles tight as you lower the weights.

An excellent way to ensure you maintain control during an exercise is to use the correct amount of weight. To determine what the correct amount of weight is for each exercise, start light, try it out, and increase the weight for each successive hard set until you’ve dialed everything in.

You also need to use a full range of motion, which means you should bend and straighten your joints as far as anatomically possible (or comfortable) during a given exercise.

For example, a full range of motion in the bench press requires that you lower the bar until it touches your chest, then press upward until your arms are straight.

Using a full range of motion is important because:

- It increases muscle and strength gain.

- It helps you avoid injury by allowing your entire joints to share the strains of strength training rather than concentrating the stress on smaller areas of your joints.

In sum, proper form is achieved when you move an appropriate weight through the right range of motion with proper technique.

How Do You Warm Up?

Doing a thorough warm-up before your first exercise in each workout helps you troubleshoot your form, “groove in” proper technique, and increase the temperature of and blood flow to your muscles, which can boost your performance and thus muscle and strength gain over time.

Here’s the protocol you want to follow before your first exercise of each workout:

- Roughly estimate what weight you’re going to use for your three sets of the exercise (this is your “hard set” weight).

- Do 6 reps with about 50% of your hard set weight, and rest for a minute.

- Do 4 reps with about 70% of your hard set weight, and rest for a minute.

Then, do all your hard sets for your first exercise and the rest of the exercises for that workout.

How Do You Progress?

As I explain in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger, the best way to maximize the muscle-building and strengthening effects of weightlifting is to strive to add weight or reps to every exercise in every workout (also known as progressive overload).

To do this effectively, follow this rule: once you hit the top of your rep range for one set, add weight.

For instance, let’s say your workout calls for 6-to-8 reps of the deadlift. If you get 8 reps for a set, add 5 pounds to each side of the bar (10 pounds total) for your next set and work with that weight until you can (eventually) lift it for 8 reps, and so forth.

If you get 5 or fewer reps with your new (higher) weight on your next sets, reduce the weight by 5 pounds to ensure you can stay within your target rep range (6-to-8) for all sets.

Follow this pattern of trying to add reps or weight to every exercise in every workout. This method is known as double progression, and it’s a highly effective way to get fitter and stronger.

How Long Should You Rest Between Sets?

Resting enough between sets is vital because it gives your heart time to settle down and prepares you to give maximum effort in your next hard set.

Research shows that resting 1-to-5 minutes between sets is optimal. In practice, the best way to do this is to rest 1-to-2 minutes between hard sets for smaller muscle groups, like the biceps, triceps, and shoulders, and slightly more (3-to-5 minutes) between hard sets for your larger muscle groups, like your back, chest, and legs.

How Often Should You Take a Break From Weightlifting?

You may have heard that you should periodically take breaks from training to allow your body to recover completely. While this can work if you’re feeling particularly beaten up, it’s rarely necessary.

A better approach is to use a deload, which involves reducing your workout volume and intensity for a period, usually a week.

I recommend you use a deload every ninth week of training using the following protocol:

- Do half as many sets as you did the previous week per exercise. (If you normally do an odd number of sets, you can decide whether to round up or down based on how ragged you’re feeling.)

- Warm up and use heavy weights as usual, but do half as many reps as the upper end of your target rep range calls for. For example, if your workout calls for 6-to-8 reps per set, then do 4 per set while deloading.

Which Supplements Should You Take?

You don’t need to take supplements to gain muscle and strength, but the right ones can help.

Here’s what I recommend for beginner weightlifters:

- 0.8-to-1.2 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day. This provides your body with the “building blocks” it needs to build and repair muscle tissue and help you recover from your workouts. If you want a clean, convenient, and delicious source of protein, try Whey+ or Casein+.

- 3-to-5 grams of creatine per day. This will boost muscle and strength gain, improve anaerobic endurance, and reduce muscle damage and soreness from your workouts. If you want a 100% natural source of creatine that also includes two other ingredients that will help boost muscle growth and improve recovery, try Recharge.

- One serving of Pulse per day. Pulse is a 100% natural pre-workout drink that enhances energy, mood, and focus; increases strength and endurance; and reduces fatigue. You can also get Pulse with caffeine or without.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about which supplements you should take to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

The Best Beginner Weightlifting Workout Program

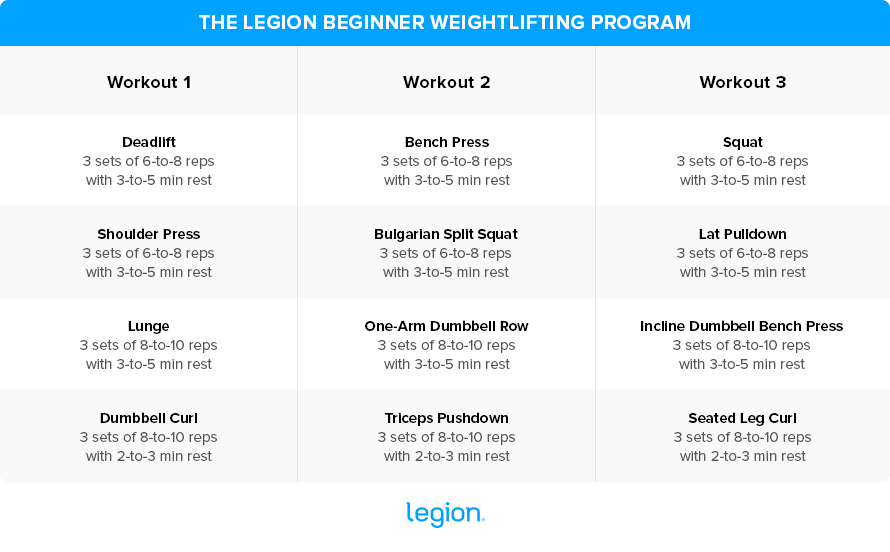

Below is a 3-day full-body beginner weightlifting routine that includes all the best muscle-building exercises and uses the right number of weekly sets to promote hypertrophy without wearing you to a frazzle.

For best results, perform each workout on non-consecutive days. For example, you could do Workout 1 on Monday, Workout 2 on Wednesday, and Workout 3 on Friday.

And if you like the look of this training program, but you’d like even more options, such as an intermediate and advanced plan, check out my fitness book for absolute beginners of any age, Muscle for Life.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Muscle for Life is right for you or if another training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, then take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Scientific References +

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- Demling, R. H., & DeSanti, L. (2000). Effect of a hypocaloric diet, increased protein intake and resistance training on lean mass gains and fat mass loss in overweight police officers. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 44(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012817

- Thomas, M. H., & Burns Phd, S. P. (2016). Increasing Lean Mass and Strength: A Comparison of High Frequency Strength Training to Lower Frequency Strength Training. International Journal of Exercise Science, 9(2), 159. /pmc/articles/PMC4836564/

- Jadczak, A. D., Makwana, N., Luscombe-Marsh, N., Visvanathan, R., & Schultz, T. J. (2018). Effectiveness of exercise interventions on physical function in community-dwelling frail older people: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(3), 752–775. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003551

- Levinger, I., Goodman, C., Hare, D. L., Jerums, G., & Selig, S. (2007). The effect of resistance training on functional capacity and quality of life in individuals with high and low numbers of metabolic risk factors. Diabetes Care, 30(9), 2205–2210. https://doi.org/10.2337/DC07-0841

- Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2013-092538

- Suchomel, T. J., Nimphius, S., Bellon, C. R., & Stone, M. H. (2018). The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 48(4), 765–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-018-0862-Z

- Rodríguez-Rosell, D., Pareja-Blanco, F., Aagaard, P., & González-Badillo, J. J. (2018). Physiological and methodological aspects of rate of force development assessment in human skeletal muscle. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 38(5), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/CPF.12495

- Seitz, L. B., Reyes, A., Tran, T. T., de Villarreal, E. S., & Haff, G. G. (2014). Increases in lower-body strength transfer positively to sprint performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44(12), 1693–1702. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-014-0227-1

- American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults - PubMed. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9624662/

- Kim, G., & Kim, J. H. (2020). Impact of Skeletal Muscle Mass on Metabolic Health. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 35(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3803/ENM.2020.35.1.1

- MacKenzie-Shalders, K., Kelly, J. T., So, D., Coffey, V. G., & Byrne, N. M. (2020). The effect of exercise interventions on resting metabolic rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 38(14), 1635–1649. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1754716

- Farinatti, P. T. V., & Castinheiras Net, A. G. (2011). The effect of between-set rest intervals on the oxygen uptake during and after resistance exercise sessions performed with large- and small-muscle mass. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(11), 3181–3190. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318212E415

- Fatouros, I. G., Chatzinikolaou, A., Tournis, S., Nikolaidis, M. G., Jamurtas, A. Z., Douroudos, I. I., Papassotiriou, I., Thomakos, P. M., Taxildaris, K., Mastorakos, G., & Mitrakou, A. (2009). Intensity of resistance exercise determines adipokine and resting energy expenditure responses in overweight elderly individuals. Diabetes Care, 32(12), 2161–2167. https://doi.org/10.2337/DC08-1994

- Osterberg, K. L., & Melby, C. L. (2000). Effect of acute resistance exercise on postexercise oxygen consumption and resting metabolic rate in young women. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 10(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.10.1.71

- Heden, T., Lox, C., Rose, P., Reid, S., & Kirk, E. P. (2011). One-set resistance training elevates energy expenditure for 72 h similar to three sets. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 111(3), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-010-1666-5

- Rome, S., Forterre, A., Mizgier, M. L., & Bouzakri, K. (2019). Skeletal muscle-released extracellular vesicles: State of the art. Frontiers in Physiology, 10(JUL), 929. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2019.00929/BIBTEX

- Vechetti, I. J., Valentino, T., Mobley, C. B., & McCarthy, J. J. (2021). The role of extracellular vesicles in skeletal muscle and systematic adaptation to exercise. The Journal of Physiology, 599(3), 845–861. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP278929

- Chen, J. F., Mandel, E. M., Thomson, J. M., Wu, Q., Callis, T. E., Hammond, S. M., Conlon, F. L., & Wang, D. Z. (2006). The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nature Genetics, 38(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.1038/NG1725

- Lopez, P., Taaffe, D. R., Galvão, D. A., Newton, R. U., Nonemacher, E. R., Wendt, V. M., Bassanesi, R. N., Turella, D. J. P., & Rech, A. (2022). Resistance training effectiveness on body composition and body weight outcomes in individuals with overweight and obesity across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 23(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/OBR.13428

- De Sousa, E. C., Abrahin, O., Ferreira, A. L. L., Rodrigues, R. P., Alves, E. A. C., & Vieira, R. P. (2017). Resistance training alone reduces systolic and diastolic blood pressure in prehypertensive and hypertensive individuals: meta-analysis. Hypertension Research : Official Journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension, 40(11), 927–931. https://doi.org/10.1038/HR.2017.69

- Bweir, S., Al-Jarrah, M., Almalty, A.-M., Maayah, M., Smirnova, I. V, Novikova, L., & Stehno-Bittel, L. (2009). Resistance exercise training lowers HbA1c more than aerobic training in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-5996-1-27

- Paquin, J., Lagacé, J. C., Brochu, M., & Dionne, I. J. (2021). Exercising for Insulin Sensitivity – Is There a Mechanistic Relationship With Quantitative Changes in Skeletal Muscle Mass? Frontiers in Physiology, 12, 635. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2021.656909/BIBTEX

- Jadczak, A. D., Makwana, N., Luscombe-Marsh, N., Visvanathan, R., & Schultz, T. J. (2018). Effectiveness of exercise interventions on physical function in community-dwelling frail older people: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 16(3), 752–775. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003551

- Ajayi-Vincent, O. B., & Adesina, M. O. (2013). EFFECTS OF RESISTANCE TRAINING ON THE BLOOD LIPID VARIABLES OF YOUNG ADULTS Introduction The enthusiasm and interest in the health benefits of resistance training continues to. European Scientific Journal, 9(12), 1857–7881.

- Villareal, D. T., Aguirre, L., Gurney, A. B., Waters, D. L., Sinacore, D. R., Colombo, E., Armamento-Villareal, R., & Qualls, C. (2017). Aerobic or Resistance Exercise, or Both, in Dieting Obese Older Adults. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(20), 1943–1955. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA1616338

- Hong, A. R., & Kim, S. W. (2018). Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 33(4), 435. https://doi.org/10.3803/ENM.2018.33.4.435

- Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S. E., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Association of Muscle Strength with the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and the Rate of Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Older Persons. Archives of Neurology, 66(11), 1339. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHNEUROL.2009.240

- Hagstrom, A. D., Marshall, P. W. M., Lonsdale, C., Papalia, S., Cheema, B. S., Toben, C., Baune, B. T., Fiatarone Singh, M. A., & Green, S. (2016). The effect of resistance training on markers of immune function and inflammation in previously sedentary women recovering from breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 155(3), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10549-016-3688-0

- N, G., A, S.-L., F, S.-G., C, F.-L., H, P.-G., E, E., & A, L. (2014). Elite athletes live longer than the general population: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(9), 1195–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2014.06.004

- Stamatakis, E., Lee, I. M., Bennie, J., Freeston, J., Hamer, M., O’Donovan, G., Ding, D., Bauman, A., & Mavros, Y. (2018). Does Strength-Promoting Exercise Confer Unique Health Benefits? A Pooled Analysis of Data on 11 Population Cohorts With All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality Endpoints. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(5), 1102–1112. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJE/KWX345

- Lee, J. H., Kim, D. H., & Kim, C. K. (2017). Resistance Training for Glycemic Control, Muscular Strength, and Lean Body Mass in Old Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Therapy, 8(3), 459. https://doi.org/10.1007/S13300-017-0258-3

- Hong, A. R., & Kim, S. W. (2018). Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 33(4), 435. https://doi.org/10.3803/ENM.2018.33.4.435

- Hashida, R., Kawaguchi, T., Bekki, M., Omoto, M., Matsuse, H., Nago, T., Takano, Y., Ueno, T., Koga, H., George, J., Shiba, N., & Torimura, T. (2017). Aerobic vs. resistance exercise in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. Journal of Hepatology, 66(1), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHEP.2016.08.023

- Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., DonCarlos, L., Hazen, N., Herman, J., Katz, E. S., Kheirandish-Gozal, L., Neubauer, D. N., O’Donnell, A. E., Ohayon, M., Peever, J., Rawding, R., Sachdeva, R. C., Setters, B., Vitiello, M. V., Ware, J. C., & Adams Hillard, P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SLEH.2014.12.010

- Liu, Y., Wheaton, A. G., Chapman, D. P., Cunningham, T. J., Lu, H., & Croft, J. B. (2016). Prevalence of Healthy Sleep Duration among Adults--United States, 2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(6), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.15585/MMWR.MM6506A1

- Ohayon, M. M. (2002). Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6(2), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1053/smrv.2002.0186

- Ohayon, M. M. (2008). Nocturnal awakenings and comorbid disorders in the American general population. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPSYCHIRES.2008.02.001

- St-Onge, M. P., Grandner, M. A., Brown, D., Conroy, M. B., Jean-Louis, G., Coons, M., & Bhatt, D. L. (2016). Sleep Duration and Quality: Impact on Lifestyle Behaviors and Cardiometabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 134(18), e367–e386. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000444

- Redline, S., Yenokyan, G., Gottlieb, D. J., Shahar, E., O’Connor, G. T., Resnick, H. E., Diener-West, M., Sanders, M. H., Wolf, P. A., Geraghty, E. M., Ali, T., Lebowitz, M., & Punjabi, N. M. (2010). Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 182(2), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1164/RCCM.200911-1746OC

- DE, F., & DB, K. (1989). Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA, 262(11), 1479–1484. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.262.11.1479

- Kojima, M., Wakai, K., Kawamura, T., Tamakoshi, A., Aoki, R., Lin Yingsong, Nakayama, T., Horibe, H., Aoki, N., & Ohno, Y. (2000). Sleep patterns and total mortality: a 12-year follow-up study in Japan. Journal of Epidemiology, 10(2), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.2188/JEA.10.87

- Rosekind, M. R., Gregory, K. B., Mallis, M. M., Brandt, S. L., Seal, B., & Lerner, D. (2010). The cost of poor sleep: workplace productivity loss and associated costs. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52(1), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0B013E3181C78C30

- Gottlieb, D. J., Ellenbogen, J. M., Bianchi, M. T., & Czeisler, C. A. (2018). Sleep deficiency and motor vehicle crash risk in the general population: a prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12916-018-1025-7

- Kovacevic, A., Mavros, Y., Heisz, J. J., & Fiatarone Singh, M. A. (2018). The effect of resistance exercise on sleep: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 39, 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SMRV.2017.07.002

- Ciccolo, J. T., Santabarbara, N. J., Dunsiger, S. I., Busch, A. M., & Bartholomew, J. B. (2016). Muscular strength is associated with self-esteem in college men but not women. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(12), 3072–3078. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315592051

- Joseph, R. P., Royse, K. E., Benitez, T. J., & Pekmezi, D. W. (2014). Physical activity and quality of life among university students: exploring self-efficacy, self-esteem, and affect as potential mediators. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 23(2), 661–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11136-013-0492-8

- Collins, H., Booth, J. N., Duncan, A., Fawkner, S., & Niven, A. (2019). The Effect of Resistance Training Interventions on ‘The Self’ in Youth: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Medicine - Open, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S40798-019-0205-0

- Gordon, B. R., McDowell, C. P., Lyons, M., & Herring, M. P. (2017). The Effects of Resistance Exercise Training on Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 47(12), 2521–2532. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-017-0769-0

- Gordon, B. R., McDowell, C. P., Hallgren, M., Meyer, J. D., Lyons, M., & Herring, M. P. (2018). Association of Efficacy of Resistance Exercise Training With Depressive Symptoms: Meta-analysis and Meta-regression Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(6), 566–576. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2018.0572

- Liu, C. ju, Shiroy, D. M., Jones, L. Y., & Clark, D. O. (2014). Systematic review of functional training on muscle strength, physical functioning, and activities of daily living in older adults. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 11(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11556-014-0144-1/FIGURES/2

- Khodadad Kashi, S., Mirzazadeh, Z. S., & Saatchian, V. (2022). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Resistance Training on Quality of Life, Depression, Muscle Strength, and Functional Exercise Capacity in Older Adults Aged 60 Years or More. Biological Research for Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1177/10998004221120945

- Kreher, J. B., & Schwartz, J. B. (2012). Overtraining syndrome: a practical guide. Sports Health, 4(2), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738111434406

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017). Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations Between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(12), 3508–3523. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002200

- Ribeiro, A. S., Dos Santos, E. D., Nunes, J. P., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2019). Acute Effects of Different Training Loads on Affective Responses in Resistance-trained Men. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(13), 850–855. https://doi.org/10.1055/A-0997-6680

- Kraemer, W. J., Fray, A. C., Warren, B. J., Stone, M. H., Fleck, S. J., Kearney, J. T., Conroy, B. P., Maresh, C. M., Weseman, C. A., Triplett, N. T., & Gordon, S. E. (1992). Acute hormonal responses in elite junior weightlifters. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 13(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2007-1021240

- Hansen, S., Kvorning, T., Kjær, M., & Sjøgaard, G. (2001). The effect of short-term strength training on human skeletal muscle: the importance of physiologically elevated hormone levels. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 11(6), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1034/J.1600-0838.2001.110606.X

- Schoenfeld, B. J., & Grgic, J. (2020). Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 205031212090155. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901559

- Pinto, R. S., Gomes, N., Radaelli, R., Botton, C. E., Brown, L. E., & Bottaro, M. (2012). Effect of range of motion on muscle strength and thickness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(8), 2140–2145. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E31823A3B15

- Fradkin, A. J., Zazryn, T. R., & Smoliga, J. M. (2010). Effects of warming-up on physical performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(1), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181C643A0

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- De Salles, B. F., Simão, R., Miranda, F., Da Silva Novaes, J., Lemos, A., & Willardson, J. M. (2009). Rest interval between sets in strength training. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 39(9), 766–777. https://doi.org/10.2165/11315230-000000000-00000

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., Schnaiter, J. A., Bond-Williams, K. E., Carter, A. S., Ross, C. L., Just, B. L., Henselmans, M., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer Interset Rest Periods Enhance Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Resistance-Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(7), 1805–1812. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272

- Willardson, J. M., & Burkett, L. N. (2008). The effect of different rest intervals between sets on volume components and strength gains. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(1), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E31815F912D

- Stokes, T., Hector, A. J., Morton, R. W., McGlory, C., & Phillips, S. M. (2018). Recent Perspectives Regarding the Role of Dietary Protein for the Promotion of Muscle Hypertrophy with Resistance Exercise Training. Nutrients, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU10020180

- Branch, J. D. (2003). Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.13.2.198

- Eckerson, J. M., Stout, J. R., Moore, G. A., Stone, N. J., Iwan, K. A., Gebauer, A. N., & Ginsberg, R. (2005). Effect of creatine phosphate supplementation on anaerobic working capacity and body weight after two and six days of loading in men and women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), 756–763. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16924.1

- Bassit, R. A., Pinheiro, C. H. D. J., Vitzel, K. F., Sproesser, A. J., Silveira, L. R., & Curi, R. (2010). Effect of short-term creatine supplementation on markers of skeletal muscle damage after strenuous contractile activity. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-009-1305-1