Key Takeaways

- The menstrual cycle refers to a series of hormonal and physiological changes that occur in a woman’s body roughly every 28 days to prepare her for pregnancy. The first half of the menstrual cycle is the follicular phase, and the second half is the luteal phase.

- Most women will perform slightly better in their workouts and experience less hunger during the follicular phase, and perform slightly worse and experience more hunger during the luteal phase.

- Keep reading to learn whether or not you should change your diet and training program based on what phase you’re in, and if so, how to do it!

As a woman, you face some challenges that guys don’t.

One of the most obvious is the menstrual cycle.

Not only can this affect your mood and daily routine, but it can also throw your diet and training plans for a loop.

If you’ve read anything about the science behind good ol’ Aunt Flo, then you probably know that it can affect your metabolism, how easily your body stores fat, and your appetite.

Your hunger and cravings intensify and your energy and enthusiasm for training wane during your period, all of which works to sabotage your fitness routine.

What should you do when this happens?

Should you stop training and start eating whatever you want, and then try to make up the damage later?

Should you force yourself to stick to your normal diet and training plan, gutting it out until you feel good again?

Or, should you modify your diet and training plan to minimize the meddling of your menses? And if so, how?

You’re going to learn the answers to all of these questions in this article.

You’ll learn . . .

- What science has to say about how the menstrual cycle affects your mood, hunger, energy levels, and enthusiasm for training.

- How to modify your training plan during your period to get the most out of your workouts.

- How to stay on track with your diet despite period-induced cravings and hunger pangs.

- And more.

Let’s get started.

- What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

- How the Menstrual Cycle Affects Your Athletic Performance

- How the Menstrual Cycle Affects Your Hunger and Cravings

- How to Optimize Your Training Around Your Menstrual Cycle

- How to Change Your Diet During Your Menstrual Cycle

- The Bottom Line on Training and Eating During Your Menstrual Cycle

Table of Contents

+What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

The menstrual cycle refers to a series of hormonal and physiological changes that occur in a woman’s body roughly every 28 days to prepare her for pregnancy.

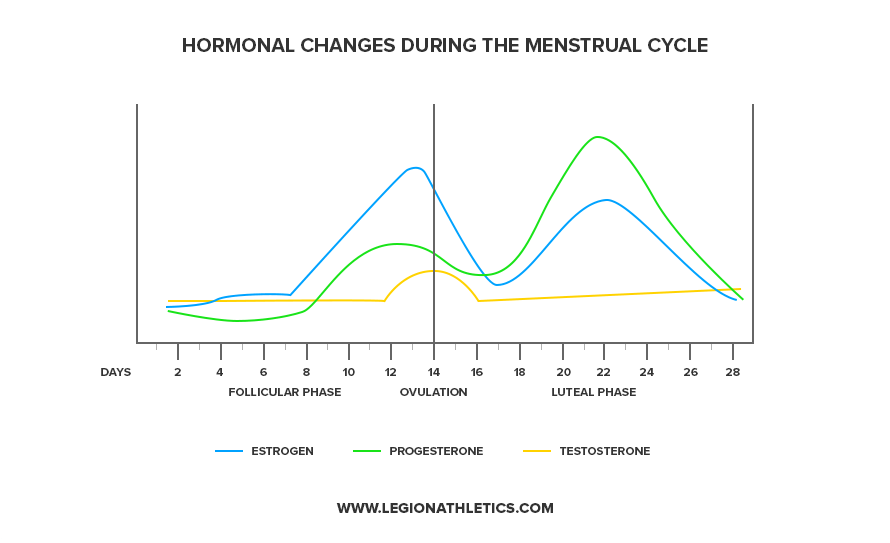

More specifically, the menstrual cycle is controlled by the interplay of blood levels of two hormones: estrogen and progesterone, which rise and fall at different points during the process.

The menstrual cycle begins with menses or menstruation, the bleeding that occurs as the uterine lining leaves the body, more commonly referred to as the “period.”

A period typically lasts three to five days, though it can be shorter or longer, and marks the beginning of the first phase of the menstrual cycle: the follicular phase.

The Follicular Phase

The first half of the 28-day menstrual period is referred to as the follicular phase, because it’s during this phase that the body releases large amounts of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH).

FSH stimulates the ovaries to produce around 10 to 20 egg-bearing pods called follicles. Though all of these follicles contain an egg, only one develops into a viable egg with the potential to become fertilized.

The follicular phase is divided into an early and late follicular phase, each lasting about seven days, based on the levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone in the blood. That is, the early follicular phase comprises roughly days 1 to 7 of the menstrual cycle, and the late follicular phase days 8 to 14.

Estrogen levels are fairly low during the early follicular phase, but begin to rise during the late follicular phase, reaching a peak just before the beginning of the luteal phase (more on this in a moment). Progesterone levels remain fairly low during most of the follicular phase, but begin to rise right at the end.

Here’s a graph showing what these hormonal changes look like over the course of the entire menstrual cycle:

Each of these hormones affects the body slightly differently.

Higher estrogen levels reduce hunger and cravings for fatty, sugary foods, improve insulin sensitivity, and stabilize blood sugar levels.

This also reduces fat storage in the lower body and abdomen, and increases concentrations of a compound called AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which boosts fat burning throughout the body.

Estrogen also has a positive effect on your training.

It reduces inflammation and free radical damage, boosts muscle growth and recovery, and decreases muscle soreness after weightlifting.

High estrogen levels may even directly improve your workout performance. For example, a study conducted by scientists at Northumbria University found that the more estrogen you have in your blood, the harder you can contract your muscles, and the more progesterone you have in your blood, the less hard you can contract your muscles.

Read: Do You Actually Want Sore Muscles? (Does It Mean Muscle Growth?)

Summary: The follicular phase is the first half of the menstrual cycle, which begins with menstruation and ends with ovulation. High estrogen levels during this phase improve workout performance and recovery and reduce hunger and fat storage.

The Luteal Phase

Around the fourteenth day of the follicular phase, the egg passes from the ovary to the Fallopian tube in a process known as ovulation.

This marks the end of the follicular phase, the middle of the menstrual cycle, and the beginning of the luteal phase.

As with the follicular phase, the luteal phase is split into an early and late phase, with each lasting about seven days. That is, the early luteal phase comprises roughly days 15 to 21 of the menstrual cycle, and the late luteal phase days 22 to 28.

After releasing the egg, the follicle created during the follicular phase transforms into a structure called the corpus luteum, which begins producing the hormone progesterone. Hence the name, luteal phase.

Fun fact: Corpus luteum is latin for “yellow body,” named for its yellow hue. It’s yellow because it contains large amounts of carotenoids, including lutein.

During the luteal phase, estrogen levels drop, which also causes a drop in serotonin and dopamine levels (the exact mechanisms are beyond the scope of this article, but when estrogen drops, so do dopamine and serotonin).

Why does this matter?

Well, serotonin and dopamine are two chemical messengers in the body that affect how the body responds to rewarding stimuli like food, sex, and entertainment, and also affect our mood and sense of well-being.

High levels of serotonin and dopamine make us feel good, which motivates us to continue doing things that make us happy and avoid things that bring us discomfort. Low levels of serotonin and dopamine can make us feel depressed, anxious, moody, and tired, and can dampen our sex drive, focus, and overall happiness.

Serotonin and dopamine also play a key role in determining our appetite and cravings.

While serotonin and dopamine levels are high, hunger and cravings are minimal. When serotonin and dopamine levels drop, though, hunger and cravings increase, especially for maximally-rewarding foods brimful with sugar and fat.

Around the same time estrogen, serotonin, and dopamine levels begin to fall (shortly after ovulation), progesterone levels rise, which causes several unpleasant physical and mental side effects. Specifically, this:

- Reduces insulin sensitivity, which increases the proportion of calories that are stored as fat and also contributes to sleepiness and mood swings.

- Increases the production of two enzymes in the body called acylation stimulating protein (ASP) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL), both of which increase fat storage (and in the case of LPL, especially in the hips, butt, and thighs).

- Interferes with testosterone’s ability to support muscle growth.

- Reduces tendon strength and recovery ability.

- Decreases the body’s ability to metabolize glucose for fuel, which reduces high-intensity exercise performance.

- Reduces the brain’s ability to recruit muscle fibers, which decreases strength and athletic performance.

- Destabilizes blood sugar levels, which increases hunger and causes energy and mood swings.

One positive effect of progesterone is that it also boosts metabolic rate anywhere from 2.5 to 10% above normal. For most people, this means burning an additional 100 to 300 calories per day or around 1,000 to 3,000 additional calories over the entire luteal phase. The downside is that unless you control your food intake, it’s easy to wipe out these “free” calories by overeating.

Luckily, you only have to suffer the effects of high progesterone levels for a few days before they reach their peak in the middle of the luteal phase, after which they decline to their low, baseline levels by the end of the menstrual cycle.

Thus, by the end of the luteal phase, estrogen and progesterone levels are both low, which contributes to what’s known as premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

We don’t need to get into the nitty gritty details of how this works, but suffice it to say that low estrogen and progesterone can cause fatigue, irritability, head and muscle aches, digestive problems and diarrhea, poor coordination and concentration, mood swings, and, well, you get the idea.

Then, at the very end of the luteal phase, estrogen rises slightly, progesterone stays low, menstruation begins, and the cycle repeats itself.

Summary: The luteal phase is the second half of the menstrual cycle, and it begins with ovulation and ends with menstruation. High progesterone levels during this phase disturb mood, decrease energy levels, and promote overeating and fat storage.

How the Menstrual Cycle Affects Your Athletic Performance

Hormones affect almost every aspect of our lives, from our mood to our metabolic rate to our motivation to exercise.

Thus, it makes sense the ebb and flow of estrogen and progesterone that occurs during the menstrual cycle would also impact your strength and endurance.

While there isn’t much scientific research on how menstruation affects athletic performance, two recent research reviews conducted by scientists at The University of Oklahoma and Loughborough University provide several clues.

The first review from The University of Oklahoma looked at how the menstrual cycle affected different endurance-related measures in women who didn’t use hormonal contraceptives (birth control).

The reason the researchers only looked at women who weren’t taking hormonal birth control is that these drugs disrupt the normal hormonal changes that occur during the menstrual cycle, and thus make it impossible to see how women’s bodies would behave under natural conditions.

The results were a mixed bag:

- One study found that women could contract their quads longer during the luteal phase than the follicular phase, whereas two other studies found that they could contract their forearm muscles longer during the follicular phase than the luteal phase. And six other similar studies found women’s performance was more or less the same regardless of what phase they were in.

- Ten studies looked at cycling endurance. One found women had greater endurance during the luteal phase, one found they had greater endurance during the follicular phase, and the other eight studies found no difference.

- Eight studies looked at running performance. One found women had better running endurance during the luteal and mid-follicular phases versus the early follicular phase, and one found they had better performance during the late follicular phase versus early follicular phase. The other studies found women ran equally well regardless of the phase they were in.

- Thirteen studies looked at women’s rating of perceived exertion (RPE) during workouts—a measure of how hard participants felt it was to exercise. In one study, women said workouts felt harder than usual during their luteal phase than the follicular phase, while women felt the opposite in three other studies. In the other nine studies, women said they felt their workouts weren’t any easier or harder regardless of the phase they were in.

So, uh, that’s about as clear as mud.

Luckily, there are a few nuggets of wisdom we can glean from this quagmire.

For one thing, the results seem to show that endurance doesn’t change much at different points across the menstrual cycle.

That is, whether you’re doing strength training or cardio, you probably won’t notice a major difference in how many reps you can do per set or how long you can maintain a certain pace in your cardio workouts, regardless of what phase of the menstrual cycle you’re in.

Read: Should You Do Cardio If You Lift Weights? Science Says Yes

It’s also possible that some people respond differently to different phases of the menstrual cycle—some people’s performance may skid during the follicular phase, others during the luteal phase, and others may not notice any difference throughout the entire cycle.

Finally, the convoluted results of this review are also partially due to the way the studies were conducted. Some involved weightlifting, some cycling, and some running. Some looked at the early follicular or luteal phases, and others the late phases, and others a combination of both. Some involved upper body muscles, and others the lower body muscles.

Thus, it’s hard to parse through the results to arrive at a conclusive answer.

Luckily, the second review brings more clarity to the matter.

The scientific review from Loughborough University examined how strength fluctuates in each phase of the menstrual cycle. They only reviewed studies that included women with a “normal” cycle (defined by the researchers as a cycle lasting between 25 and 31 days for more than 6 months) who were not taking hormonal contraceptives or receiving hormone replacement therapy.

The researchers found 21 studies that met these criteria. All told, they included results from 232 women between the ages of 19 and 33 years old with a wide range of athletic abilities, ranging from couch potatoes to elite athletes.

In some of the studies, the researchers also looked at the women’s levels of estrogen and progesterone throughout their menstrual cycles and compared these to their strength.

The results?

The researchers found that no matter how the studies measured strength, it didn’t seem to change at all across the menstrual cycle. They also found there was no relationship between strength and estrogen and progesterone levels.

If this has you scratching your head, I don’t blame you.

After all, it seems like a rule of nature that most women say they feel more tired and weaker during their period, and yet all of these studies say that shouldn’t be the case.

Well, it turns out that this seeming paradox is probably due to the way these studies were designed and conducted.

For example, it’s very difficult for researchers to accurately determine what phase of the menstrual cycle women are in at any one time. What’s more, this is a moving target, and can change from month to month (a woman’s menstrual cycle rarely lasts exactly 28 days).

It’s also hard for researchers to control for other variables that can impact a woman’s strength over the course of a study. Diet, sleep, stress, stimulants, and other wildcards can easily increase or decrease strength.

Finally, and most importantly, although there wasn’t a statistically significant difference in strength across the menstrual cycle, there was a trend for women to perform better in the follicular phase and early luteal phase (during ovulation).

This also makes sense based on what we know about hormone levels during the follicular phase. This is when estrogen is highest and progesterone is lowest, which would theoretically be the ideal scenario for workout performance and recovery.

As a corollary, the results also show a slight trend for women to be weaker during their luteal phase and during menstruation.

Again, this jives with what most women experience. During and just before their period, they tend to feel a little more fatigued, weak, and unmotivated to train.

Several other studies not included in this review lend support to this idea.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at the Institute for Sports Science in Berlin had 20 untrained women follow a strength training program for five complete menstrual cycles (about five months).

Read: The 12 Best Science-Based Strength Training Programs for Gaining Muscle and Strength

The women lifted weights on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and did 3 sets of 8 to 10 reps of leg press using 80% of their one-rep max. They took each set to failure, rested 3 to 5 minutes between sets, and if they were able to get 12 reps in one set, the researchers increased the weight on their subsequent sets.

The women also had to complete one workout per week at home (on Saturdays), where they did 3 sets of 15 to 20 one-legged squats, again with three to five minutes rest between sets.

All of the participants measured and recorded their body temperature every morning immediately after waking so the researchers could track what phase of the menstrual cycle they were in. (Although this method might seem unscientific, it’s an accurate way to track changes in the menstrual cycle).

The researchers also measured leg extension strength around day 11 and day 25 of each cycle, and measured the circumference of the participant’s rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis muscles on day 25 of each cycle. They also took muscle biopsies (samples) from the vastus lateralis muscle on day 27 of each cycle.

There’s a twist to this study, though: the women trained one leg during the follicular phase of their cycle, and trained the other leg during the luteal phase of their cycle.

Participants changed their training leg as soon as their body temperature increased more than 0.3 degrees Celsius for three consecutive days (signalling the transition from the follicular phase to the luteal).

For example, a woman might have trained her right leg during her follicular phase, and her left leg during her luteal phase, switching back and forth roughly every two weeks. By the end of the study, each leg had gone through about 28 workouts each.

The result?

The women gained significantly more muscle and strength in the legs trained during the follicular phase versus the legs trained during the luteal phase.

Again, this lines up with what we know about how female hormones change throughout the cycle. Estrogen increases muscle building and improves muscle recovery, and estrogen levels tend to be highest during the follicular phase. What’s more, progesterone tends to reduce workout performance in several subtle ways, and progesterone levels tend to be lowest during the follicular phase.

So, what does all of this mean for you?

On the one hand, most research shows there probably isn’t much of a difference in performance across the menstrual cycle—you’ll have just as much strength and endurance during the luteal phase as the follicular phase, and vice versa. This includes the week of your period, and the few days prior when you might be suffering from symptoms of PMS.

It’s also worth remembering that women have won Olympic medals during all phases of their menstrual cycle, so if there is a drop in performance at certain times, it’s not a game-changer. What’s more, research shows that exercise reduces the symptoms of PMS, so it’s probably not a good idea to stop training even when you don’t feel like you’re at your best.

On the other hand, some research does suggest that you may perform a little better (both in terms of strength and endurance) and respond better to your workouts during the follicular phase of your training.

So, should you modify your workout plan to coincide with the phases of your menstrual cycle?

It depends:

No . . . if you don’t notice much of a difference in your strength or endurance and you’re making good progress following your current workout routine. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, and all that.

Yes . . . if you feel like your strength, endurance, and motivation to train take a nosedive before and during your period, your progress has stalled, or you just enjoy tinkering with your training program.

Summary: Most research shows your strength and endurance don’t change much throughout the menstrual cycle. That said, some data suggests you might perform a little better and recover faster from your training during the follicular phase and fare worse during the luteal phase.

How the Menstrual Cycle Affects Your Hunger and Cravings

While the jury’s still out on how much the menstrual cycle affects athletic performance, it most definitely does affect hunger and fat storage.

For example, research shows that estrogen decreases hunger and increases the production of another hormone called leptin.

If you want to learn more about how leptin affects your ability to lose weight, read this article, but the long story short is that higher levels of leptin make it easier to lose weight in just about every way—it reduces hunger, increases your motivation to exercise, and directly boosts your metabolic rate and mood.

Read: Everything You Need to Know About Leptin Resistance and Weight Loss

Estrogen not only causes your body to release more leptin, it also mimics the effects of leptin in the brain, compounding its benefits.

What high estrogen giveth, though, low estrogen taketh away.

That is, while you get to enjoy the benefits of high estrogen levels during the middle of your follicular and luteal phases, you also have to deal with the negative effects of low estrogen levels the rest of the time.

As estrogen levels fall after ovulation, leptin sinks and hunger and cravings increase.

Remember that estrogen also increases the production of serotonin and dopamine, which reduces hunger and cravings. As estrogen levels fall, so do serotonin and dopamine levels, allowing hunger and cravings to rear their heads again.

Low levels of serotonin are particularly problematic, because this can cause intense carbohydrate cravings and increase the risk of binge eating.

What’s more, serotonin improves mood and feelings of well-being, but the body requires some carbohydrate to optimize serotonin production. Thus, one of the reasons many women crave carbs before their period is probably because their bodies are encouraging them to boost serotonin production (and thus their mood) by noshing carbs.

In other words, your brain is literally urging you to eat yourself happy.

Eating carbs isn’t a bad thing in and of itself, but the problem is many women get their fix with highly-refined, high-calorie, high-fat foods like cakes, breakfast cereals, candy, potato chips, and ice cream, not nutritious, high-fiber, filling foods like oatmeal, sweet potatoes, fruit, and whole grains.

At the same time all of this is going on, progesterone levels are rising, which further increases hunger.

Not only does progesterone increase food cravings, it also reduces insulin sensitivity, which can cause mood and energy swings and hunger.

Summary: High estrogen levels during the follicular phase reduce hunger and cravings and promote fat burning, but low estrogen levels during the luteal phase cause the opposite effect: boosting hunger and cravings and promoting fat storage.

How to Optimize Your Training Around Your Menstrual Cycle

As you learned a moment ago, you don’t have to calibrate your workout program to your menstrual cycle to make fantastic progress in the gym.

In fact, if doing so makes it harder to stick to your program, then it’s not worth the hassle.

If this is the case for you, follow your normal training routine regardless of what phase of the menstrual cycle you’re in, and accept that you may not progress as quickly or feel as buoyant during the end of your menstrual cycle.

That said, some research shows that you may be able to get slightly better results from your training by orienting your program around your menstrual cycle.

Remember that during the first two weeks or so of your menstrual cycle—the follicular phase—you may be able to perform more reps and sets and lift more weight in your workouts, recover faster, and build more muscle as a result.

During the next week or so after ovulation—the early luteal phase—your performance might skid a little, but you should still feel pretty good on the whole.

Then, during the last phase of your menstrual cycle—the late luteal phase—your performance will probably take a hit and you won’t have as much energy to train. This will likely start around the same time as the other effects of premenstrual syndrome and persist until the end of your period (around 5 to 7 days in total).

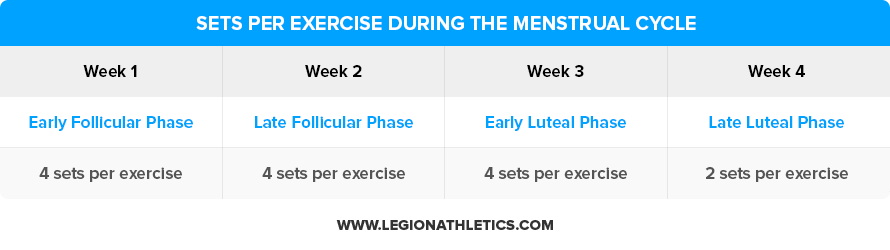

Thus, a smart way to optimize your workouts in relation to your menstrual cycle would be to plan more intense workouts during the first three weeks of the cycle followed by easier workouts during the last week.

What do I mean by “more intense workouts,” exactly?

Two things:

- Aggressively pushing to add weight or reps in every workout. You can read this article to learn more about the science behind this strategy, but the bottom line is this is the most effective way to gain muscle and strength.

- Doing more hard sets. This involves doing more heavy, muscle- and strength-building sets that are taken close to technical failure (the point where you can no longer continue with proper form) for each muscle group.

These are the two sides to the muscle- and strength-building coin.

When it comes to increasing progressive overload, I recommend you use a technique called double progression, which involves increasing the weight for an exercise after hitting the top end of your rep range for one set.

For instance, let’s say you’re doing the barbell bench press for 4 to 6 reps.

If you press 95 pounds for 6 reps on your first set, you add 5 pounds to each side of the bar for your next set.

If, on the next set, you can get at least 4 reps with 145 pounds, that’s the new weight you work with until you can press it for 6 reps, move up, and so forth.

If you get 3 or fewer reps, though, reduce the weight added by 5 pounds (140 pounds) and see how the next set goes. If you still get 3 reps or fewer, reduce the weight to the original 6-rep load and work with that until you can do two 6-rep sets with it, and then increase the weight on the bar.

You can learn more about how to use double progression in this podcast:

Listen: How to Use Double Progression to Get More From Your Workouts

When it comes to training around your menstrual cycle, you’d want to try to add weight and reps in every workout during the first three weeks, then focus on maintaining the same weight and reps for each exercise during the last week of your cycle.

To do more hard sets, well, you just do more hard sets.

For example, if you’re doing three sets per exercise right now, do four during the first three weeks of your period. Then, during the last week of your period, you could drop this down to two sets per exercise to give your body a breather.

Here’s what this would look like:

Basically, you’re just training harder than usual for three weeks, then deloading for one week.

In case you aren’t familiar with the concept, a deload is a period of reduced training volume and/or intensity to give your body time to recuperate and prepare for more hard training.

In this case, you’re deloading by cutting your volume (number of sets per exercise) in half, and maintaining your intensity (the weight you use for each exercise).

Read: How to Use Deloads to Gain Muscle and Strength Faster

Summary: You don’t need to change your training program based on your menstrual cycle, but doing so might help you gain muscle and strength slightly faster than you would otherwise.

How to Change Your Diet During Your Menstrual Cycle

When it comes to your diet, the first two weeks of your menstrual cycle should be smooth sailing.

Your hunger and energy levels and mood should all be fairly stable, cravings should be minimal, and you shouldn’t have to change much of anything about your diet to stay on track.

The next two weeks of your period are more difficult to navigate.

Hunger and cravings rise, your body stores fat more easily, and you’ll also probably be a little less motivated to stay physically active. For most women, all of this reaches a crescendo shortly before your period (premenstrual syndrome), which is when overeating or outright binging becomes more likely.

There are a few things you can do to at least partially mitigate these issues:

1. Schedule any cheat meals or restaurant outings during your follicular phase, when you’re least likely to overeat or turn a cheat meal into a cheat day (or week).

It may seem counterintuitive to plan your cheat meals when you’re least excited about food, but it’s much easier to control yourself when you aren’t preoccupied with food.

2. Be fastidious about meal planning during your luteal phase. You’ll probably want to overeat, and a meal plan acts like a set of guardrails to keep you on track.

This means keeping your fridge and pantry stocked with healthy foods, weighing ingredients as you cook, and preparing any meals you eat outside of the house ahead of time and bringing them with you.

3. Eat slightly more calories during your luteal phase, or at least immediately before and during your period.

Again, the idea here is to tame your hunger and help you stay satisfied so you don’t overeat. If this sounds like more of a hassle than it’s worth, though, just eat the same number of calories during your entire menstrual cycle.

(And if you’d like specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

If you’re currently trying to lose weight, research also shows that taking periodic breaks from your diet like this can improve your results (regardless of what phase of the menstrual cycle you’re in, or whether you’re a man or a woman).

Read: Research Review: Can “Cheating” on Your Diet Help You Lose Fat Faster?

Summary: You don’t need to change your diet during any phase of your menstrual cycle, but you’ll probably find it easier to control your cravings during the follicular phase, and may want to eat slightly more during the luteal phase to keep hunger at bay.

The Bottom Line on Training and Eating During Your Menstrual Cycle

The menstrual cycle refers to a series of hormonal and physiological changes that occur in a woman’s body roughly every 28 days, which are largely dictated by the ebb and flow of estrogen and progesterone.

The first half of the menstrual cycle is referred to as the follicular phase, and the second half is referred to as the luteal phase, both of which last around 14 days.

During the follicular phase, estrogen levels are high, which means your mood, motivation, and ability to recover from your workouts will likely be high, and hunger and cravings will probably be low.

Estrogen also causes a number of other physiological changes that make it harder to gain fat during the follicular phase.

During the luteal phase, estrogen levels decrease and progesterone levels increase, which means your mood, motivation to train, and ability to recover from workouts will drop, and hunger, cravings, and the likelihood of fat gain will rise.

Luckily, most research shows these changes have a fairly small impact on your training. While you might have slightly more productive workouts during your follicular phase, you don’t have to change your training program if you’re currently making good progress.

If your progress has stalled or you tend to notice a big drop in your performance during the luteal phase, it may be a good idea to train harder during the first three weeks of your menstrual cycle and take the last week a bit easier.

When it comes to your diet, you’ll want to be wary of overeating during your luteal phase.

To that end, you can schedule cheat meals during your follicular phase (when you’re less tempted to overeat), and be more diligent about planning and preparing meals during the luteal phase. You may also want to eat slightly more during the luteal phase to take your hunger down a notch.

All in all, the big takeaway here is that planning your training program and diet around your menstrual cycle isn’t complicated.

Any potential benefits are fairly small, and if you’d rather stick with your current eating and exercise regimen, you aren’t missing much (if anything).

If you want to make slightly faster progress in your workouts or you’re having trouble losing weight with your current program, though, give the steps in this article a whirl.

What’s your take on the menstrual cycle? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Byrne, N. M., Sainsbury, A., King, N. A., Hills, A. P., & Wood, R. E. (2018). Intermittent energy restriction improves weight loss efficiency in obese men: The MATADOR study. International Journal of Obesity, 42(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.206

- Bruns, C. M., & Kemnitz, J. W. (2004). Sex hormones, insulin sensitivity, and diabetes mellitus. In ILAR journal / National Research Council, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (Vol. 45, Issue 2, pp. 160–169). ILAR J. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar.45.2.160

- Arnoni-Bauer, Y., Bick, A., Raz, N., Imbar, T., Amos, S., Agmon, O., Marko, L., Levin, N., & Weiss, R. (2017). Is it me or my hormones? neuroendocrine activation profiles to visual food stimuli across the menstrual cycle. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 102(9), 3406–3414. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-3921

- Fernández-Ruiz, J. J., de Miguel, R., Hernández, M. L., & Ramos, J. A. (1990). Time-course of the effects of ovarian steroids on the activity of limbic and striatal dopaminergic neurons in female rat brain. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 36(3), 603–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(90)90262-G

- Wurtman, R. J., & Wurtman, J. J. (1986). Carbohydrate craving, obesity and brain serotonin. Appetite, 7, 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(86)80055-1

- Yonkers, K. A., O’Brien, P. S., & Eriksson, E. (2008). Premenstrual syndrome. In The Lancet (Vol. 371, Issue 9619, pp. 1200–1210). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60527-9

- Dye, L., & Blundell, J. E. (1997). Menstrual cycle and appetite control: Implications for weight regulation. Human Reproduction, 12(6), 1142–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/12.6.1142

- Wurtman, R. J., & Wurtman, J. J. (1995). Brain serotonin, carbohydrate-craving, obesity and depression. In Obesity research: Vol. 3 Suppl 4. Obes Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00215.x

- Hirschberg, A. L. (2012). Sex hormones, appetite and eating behaviour in women. In Maturitas (Vol. 71, Issue 3, pp. 248–256). Maturitas. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.016

- Barth, C., Villringer, A., & Sacher, J. (2015). Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. In Frontiers in Neuroscience (Vol. 9, Issue FEB). Frontiers Research Foundation. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00037

- Davidsen, L., Vistisen, B., & Astrup, A. (2007). Impact of the menstrual cycle on determinants of energy balance: A putative role in weight loss attempts. In International Journal of Obesity (Vol. 31, Issue 12, pp. 1777–1785). Int J Obes (Lond). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803699

- Gao, Q., & Horvath, T. L. (2008). Cross-talk between estrogen and leptin signaling in the hypothalamus. In American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism (Vol. 294, Issue 5). Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00733.2007

- Butera, P. C. (2010). Estradiol and the control of food intake. Physiology and Behavior, 99(2), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.010

- Daley, A. (2009). The role of exercise in the treatment of menstrual disorders: The evidence. In British Journal of General Practice (Vol. 59, Issue 561, pp. 241–242). Royal College of General Practitioners. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X420301

- Kishali, N. F., Imamoglu, O., Katkat, D., Atan, T., & Akyol, P. (2006). Effects of menstrual cycle on sports performance. International Journal of Neuroscience, 116(12), 1549–1563. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450600675217

- Brown, M. (2013). Estrogen effects on skeletal muscle. In Integrative Biology of Women’s Health (pp. 35–51). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8630-5_3

- Velders, M., & Diel, P. (2013). How sex hormones promote skeletal muscle regeneration. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 43, Issue 11, pp. 1089–1100). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0081-6

- Steward, K., & Raja, A. (2019). Physiology, Ovulation, Basal Body Temperature. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31536292

- Sung, E., Han, A., Hinrichs, T., Vorgerd, M., Manchado, C., & Platen, P. (2014). Effects of follicular versus luteal phase-based strength training in young women. SpringerPlus, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-668

- Wikström-Frisén, L., Boraxbekk, C. J., & Henriksson-Larsén, K. (2017). Effects on power, strength and lean body mass of menstrual/oral contraceptive cycle based resistance training. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 57(1–2), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.16.05848-5

- Blagrove, R. C., Bruinvels, G., & Pedlar, C. R. (2020). Variations in strength-related measures during the menstrual cycle in eumenorrheic women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.04.022

- Pereira, H. M., Larson, R. D., & Bemben, D. A. (2020). Menstrual Cycle Effects on Exercise-Induced Fatigability. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 517. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00517

- Howe, J. C., Rumpler, W. V., & Seale, J. L. (1993). Energy expenditure by indirect calorimetry in premenopausal women: variation within one menstrual cycle. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 4(5), 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/0955-2863(93)90096-F

- Sugaya, A., Sugiyama, T., Yanase, S., Shen, X. X., Minoura, H., & Toyoda, N. (2000). Expression of glucose transporter 4 mRNA in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of ovariectomized rats treated with sex steroid hormones. Life Sciences, 66(7), 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00636-0

- Tenan, M. S., Hackney, A. C., & Griffin, L. (2016). Maximal force and tremor changes across the menstrual cycle. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 116(1), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-015-3258-x

- Oosthuyse, T., & Bosch, A. N. (2010). The effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise metabolism: Implications for exercise performance in eumenorrhoeic women. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 40, Issue 3, pp. 207–227). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/11317090-000000000-00000

- Chidi-Ogbolu, N., & Baar, K. (2019). Effect of estrogen on musculoskeletal performance and injury risk. In Frontiers in Physiology (Vol. 10, Issue JAN, p. 1834). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01834

- Hansen, M., & Kjaer, M. (2014). Influence of sex and estrogen on musculotendinous protein turnover at rest and after exercise. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 42(4), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000026

- MARTIN, D., & ELLIOTT-SALE, K. (2016). A perspective on current research investigating the effects of hormonal contraceptives on determinants of female athlete performance. Revista Brasileira de Educação Física e Esporte, 30(4), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-55092016000401087

- Saleh, J., Al-Wardy, N., Farhan, H., Al-Khanbashi, M., & Cianflone, K. (2011). Acylation stimulating protein: A female lipogenic factor? Obesity Reviews, 12(6), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00832.x

- Rebuffe Scrive, M., Basdevant, A., & Guy Grand, B. (1983). Effect of local application of progesterone on human adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase. Hormone and Metabolic Research, 15(11), 566. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1018791

- Bruns, C. M., & Kemnitz, J. W. (2004). Sex hormones, insulin sensitivity, and diabetes mellitus. In ILAR journal / National Research Council, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (Vol. 45, Issue 2, pp. 160–169). ILAR J. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar.45.2.160

- Dye, L., & Blundell, J. E. (1997). Menstrual cycle and appetite control: Implications for weight regulation. Human Reproduction, 12(6), 1142–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/12.6.1142

- Cross, G. B., Marley, J., Miles, H., & Willson, K. (2001). Changes in nutrient intake during the menstrual cycle of overweight women with premenstrual syndrome. British Journal of Nutrition, 85(4), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn2000283

- Hirschberg, A. L. (2012). Sex hormones, appetite and eating behaviour in women. In Maturitas (Vol. 71, Issue 3, pp. 248–256). Maturitas. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.016

- L Meisel, R., & E Been, L. (2019). Dopamine. In Encyclopedia of Sexuality and Gender (pp. 1–8). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-59531-3_10-1

- Cowen, P. J., & Browning, M. (2015). What has serotonin to do with depression? In World Psychiatry (Vol. 14, Issue 2, pp. 158–160). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20229

- Berke, J. D. (2018). What does dopamine mean? In Nature Neuroscience (Vol. 21, Issue 6, pp. 787–793). Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0152-y

- Jenkins, T. A., Nguyen, J. C. D., Polglaze, K. E., & Bertrand, P. P. (2016). Influence of tryptophan and serotonin on mood and cognition with a possible role of the gut-brain axis. In Nutrients (Vol. 8, Issue 1). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8010056

- Amin, Z., Canli, T., & Epperson, C. N. (2005). Effect of estrogen-serotonin interactions on mood and cognition. In Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews (Vol. 4, Issue 1, pp. 43–58). Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582305277152

- Ansdell, P., Brownstein, C. G., Skarabot, J., Hicks, K. M., Simoes, D. C. M., Thomas, K., Howatson, G., Hunter, S. K., & Goodall, S. (2019). Menstrual cycle-associated modulations in neuromuscular function and fatigability of the knee extensors in eumenorrheic women. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(6), 1701–1712. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01041.2018

- Chidi-Ogbolu, N., & Baar, K. (2019). Effect of estrogen on musculoskeletal performance and injury risk. In Frontiers in Physiology (Vol. 10, Issue JAN, p. 1834). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01834

- Hansen, M., & Kjaer, M. (2014). Influence of Sex and Estrogen on Musculotendinous Protein Turnover at Rest and After Exercise. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 42(4), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000026

- Tiidus, P. M. (2000). Estrogen and gender effects on muscle damage, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, 25(4), 274–287. https://doi.org/10.1139/h00-022

- Yang, S., & Wang, J. (2015). Estrogen Activates AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Human Endothelial Cells via ERβ/Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase Kinase β Pathway. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics, 72(3), 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-015-0521-z

- Price, T. M., O’Brien, S. N., Welter, B. H., George, R., Anandjiwala, J., & Kilgore, M. (1998). Estrogen regulation of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase - Possible mechanism of body fat distribution. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 178(1 I), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70634-9

- Brown, L. M., & Clegg, D. J. (2010). Central effects of estradiol in the regulation of food intake, body weight, and adiposity. In Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (Vol. 122, Issues 1–3, pp. 65–73). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.12.005

- Findlay, J. K. (2003). Folliculogenesis. In Encyclopedia of Hormones (pp. 653–656). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-341103-3/00141-8

- Reed, B. G., & Carr, B. R. (2000). The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. In Endotext. MDText.com, Inc. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25905282