Key Takeaways

- Tight hip flexors probably aren’t caused solely by sitting, heavy lifting, or lack of stretching.

- Stretching can help reduce hip flexor tightness, but not by making you more flexible.

- Paradoxically, strengthening your hip flexors may reduce tightness.

If you’re like most people, your hips feel tight all the time, and especially right at the top of your thighs.

They probably flare up when you do lower body exercises too, like the squat and deadlift.

Such is life with tight hip flexor muscles.

What can you do about it, though? Should you stretch? Strengthen? Something else altogether?

Well, poke around on the Internet and you’ll find a lot of conflicting opinions on what causes tight hip flexors and what to do about it.

Some people say that sitting is to blame because it shortens and weakens the muscles, others say exercise–and weightlifting in particular–is at fault, and others still say that muscle weakness is the root cause.

There isn’t much agreement about how to best fix the problem, either.

“Stretching is the key,” says one expert. “No,” counters the other, “strengthening must come first.”

And there you are in the middle, wondering whom to believe and what to do.

Well, the truth is hip flexor tightness isn’t as cut and dried as many people would have you believe. As you’ll see, causation is murky and “magic bullet” fixes are unlikely.

The good news, though, is you don’t have to know exactly why your hip flexors are acting up to figure out how to fix it, and with a little trial and error, you can do just that.

Let’s start at the top…

- What Are Hip Flexors?

- What Causes Tight Hip Flexors?

- The Best Stretches for Tight Hip Flexors

- The Best Exercises for Strengthening Hip Flexors

- The Bottom Line on Hip Flexors

Table of Contents

+Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

What Are Hip Flexors?

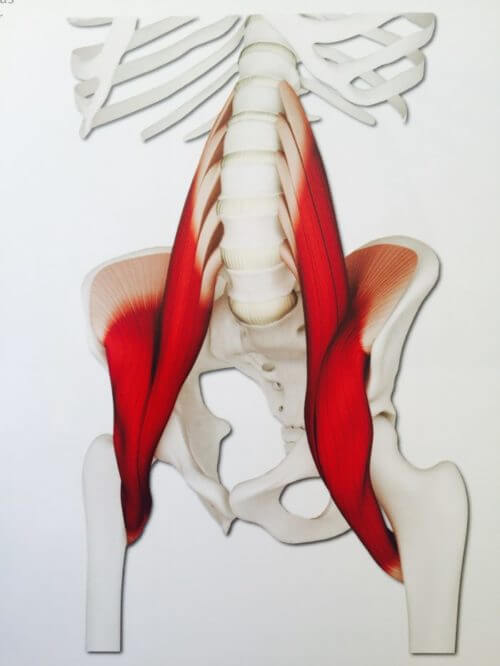

The hip flexors are a group of muscles that connect the pelvis to the upper leg.

These muscles are involved in just about every kind of movement that involves your lower body, including exercises like the squat, deadlift, overhead press, and even bench press.

There are quite a few hip flexors, including:

- Iliopsoas

- Rectus femoris

- Sartorius

- Tensor fasciae latae

- Pectineus

- Adductor longus

- Adductor brevis

- Gracilis

And here’s what they look like:

They’re called hip flexors because they create flexion in the hip, which is the technical term for a bending movement around a joint in a limb (such as the knee or elbow) that decreases the angle between the bones of the limb at the joint.

For example, when you raise your knee, hip flexion occurs because it decreases the angle of your thigh bone relative to your hip joint.

(In case you’re wondering, the opposite of flexion is extension, which occurs when you lower your knee from a flexed position.)

What Causes Tight Hip Flexors?

The scapegoat du jour for tight hip flexors is sitting, even for short periods.

“Sitting is the new smoking,” we’re told, because it purportedly increases the risk of all kinds of disease and dysfunction (a claim that appears to be more wrong than right, by the way).

As far as the hip flexors go, the theory is that sitting tightens these muscles by forcing them to remain contracted (and thus shortened) for extended periods of time.

Another popular theory is that tight hip flexors are caused by overuse.

The idea is the more you punish these muscles with intense exercise, and especially weightlifting, the more likely they are to become and remain tight.

Many people also say that the tightness you feel in your hip flexors is caused by a combination of both of these factors.

These ideas sound plausible enough, but basic physiology indicates otherwise.

For example, sitting can’t permanently or even temporarily “shorten” your hip flexors because muscles can’t change in length–they can simply become bigger or smaller.

It’s also unlikely that weightlifting is to blame.

Research shows that strength training improves muscle and tendon function, and is often used as a tool for rehabilitating joint pains and problems.

It’s certainly possible to injure your hip flexors in the gym, but it’s unlikely that weight training can otherwise saddle you with perpetually tight hip flexors.

Moving down the list, studies also show that hip flexor tightness probably isn’t caused by weakness, either.

While strengthening the hip flexor muscles can relieve the feeling of tightness, research suggests that weak muscles aren’t more prone to tightness than strong ones.

So, where does that leave us, then? What the hell really causes tight hip flexor muscles?

Well, as you’ve probably guessed by now, we haven’t quite figured it out yet.

Muscle pain and tightness are rather mysterious phenomena, and many of things that have long been assumed to produce them have been debunked.

For example, you’ve probably heard that sitting too much inevitably causes low-back tightness, but a number of studies have shown this to be false.

I have good news, though:

You don’t have to suffer through life with “incurable shitty hip flexors” while science sorts the mess out.

With a handful of stretches and exercises, you can get relief and also probably improve your lower body workouts because impaired lower body mobility is one of the most common things that gets in the way of proper squatting, deadlifting, and the like.

Let’s start with hip flexor stretches.

The Best Stretches for Tight Hip Flexors

If a muscle is tight, our first instinct is to stretch it.

Well, while stretching can benefit our body in many ways, it isn’t a panacea for muscle tightness. It may or may not help, depending on what’s causing the problem.

That’s why a simple trial and error approach is best with stretching tight muscles, and tight hip flexors in particular.

Do one of these stretches several times per day for several days and see if it makes your hip flexors feel looser and less aggravated.

If it does, make a note and move on to the next stretch, and after trying all of them, continue doing those that helped.

Hip Flexor Stretch #1

Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch

This is one of the best stretches for targeting the hip flexors.

Work on this for 2 to 3 minutes per leg per stretching session.

Hip Flexor Stretch #2

Psoas Quad Stretch

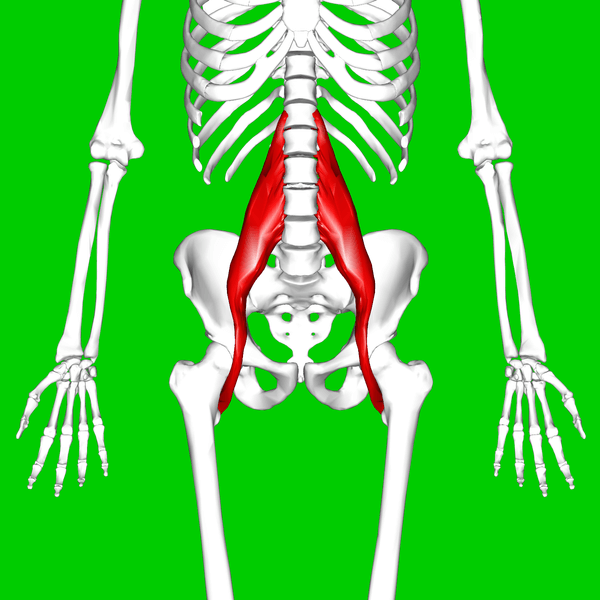

The psoas is a powerful pelvic muscle that plays a key role in hip flexion. Here’s what it looks like:

When this muscle is tight, it’s common to experience lower back discomfort and it makes heavy squatting more or less impossible.

You perform this stretch by assuming the position, and then driving your knee into the ground and leaning forward into a deep stretch, and then releasing.

Perform this drive and release pattern for 2 to 3 minutes per leg per stretching session.

Hip Flexor Stretch #3

Walking Knee Hug

This is another simple but effective hip flexor stretch that might help loosen your hips up.

This stretch also targets your glutes, which are also very often tight.

Do 10 to 12 knee hugs per leg per stretching session, holding the top position for 1 to 2 seconds each time.

Hip Flexor Stretch #4

Rocking Psoas Stretch

This is another psoas stretch with many variations. Play around with it and find what is best (or just most convenient) for you.

Work on this for 2 to 3 minutes per leg per stretching session.

Hip Flexor Stretch #5

Rectus Femoris Stretch

This stretch targets one of the largest hip flexors, the rectus femoris (one of the quadriceps muscles).

Work on this for 2 to 3 minutes per leg per stretching session.

Hip Flexor Stretch #6

Scorpion Stretch

This stretch is fantastic for your hip flexors, glutes, and lower back.

Do 4 to 5 repetitions per side per stretching session.

The Best Exercises for Strengthening Hip Flexors

You know by now that eliminating hip flexor tightness isn’t an exact science. You have to try various things and see what works.

Strengthening your hip flexors is one of those things.

As with stretching, you can’t know for sure if it’s going to help, but if nothing else, it’ll improve your joint health, generally reduce muscle-related pains, reduces overall muscular pain, and give you a great set of legs to boot.

Now, out of all the hip flexor exercises you could do, a small handful stand head and shoulders above the rest.

Incorporate these exercises into your lower body workouts, build your strength on them, and there’s a good chance your hip flexors will feel better and better.

Hip Flexor Exercise #1

Barbell Back Squat

If you’re not doing at least some form of squatting regularly, your lower body is missing out.

And out of all the squat variations you can do, the plain old barbell back squat is hard to beat.

It has earned the reputation as the single most effective exercise you can do for building a solid, strong lower body because, well, it is.

It goes further than that too, because it’s actually a whole-body exercise that involves every major muscle group but your chest.

Here’s an in-depth discussion on how to squat properly:

There are several things here that I want to highlight:

- The thighs are slightly below parallel to the ground at the bottom of the squat, putting the butt slightly below the knees.

- The knees are slightly in front of the toes at the bottom.

- The head position remains neutral, looking at a point on the ground about 6 to 8 feet away.

- The spine remains neutral as well, never arching or rounding.

- The chest stays up, forcing the shoulders back.

These are the key elements of safe and effective squatting.

Hip Flexor Exercise #2

Barbell Front Squat

The front squat is a squat variation that emphasizes the quadriceps and core and requires less flexibility than the back squat.

It also creates less compression of the spine and less torque in the knees, which makes it particularly useful for those with back or knee injuries or limitations.

Mechanically, speaking, it’s very similar to the back squat, but you hold the bar differently.

Here’s how it works:

Hip Flexor Exercise #3

Lunge

The lunge is a simple but effective leg exercise that everyone can benefit from.

It builds strength, muscle, and balance, and because it’s a single-leg movement, it can help address muscular imbalances as well.

If you’re new to lunging, the dumbbell lunge is the place to start. Here’s how to do it:

The barbell lunge is a more difficult variation but it allows you to use heavier weights and thus better progressively overload your muscles:

Hip Flexor Exercise #4

Leg Press

Many people consider the leg press an inferior version of the squat.

I disagree.

It not only requires less technical skill (making it more newbie-friendly) and stabilizing muscles (allowing you to load heavier weights), it also is fantastic for building hip strength (due to its large range of motion).

Here’s how to do it on an angled press (which I prefer):

And here’s a seated press:

Hip Flexor Exercise #5

Bulgarian Split Squat

It’s rare to see someone doing Bulgarian split squats, which is a shame.

Unbeknownst to many, the split squat is a fantastic unilateral leg exercise, and is particularly effective for training your hamstrings, hip flexors, and glutes.

That’s why it’s quickly gaining popularity among high-level strength and conditioning coaches.

Here’s how to do it:

Hip Flexor Exercise #6

Barbell Step-Up

It doesn’t look like much, but the step-up is a great single-leg exercise for working your hip flexors (among your other leg muscles).

As with the lunge, the dumbbell step-up is the place to start.

Here’s how to do it:

As you get stronger and need to continue increasing the weight, you can graduate to the barbell step-up:

The Bottom Line on Hip Flexors

When your hip flexors are tight, they never stop nagging you.

You feel them when you lay, sit, stand, walk, and work out, and it really gets in the way if you’re serious about your lower body training.

Trying to fix the problem can be equally frustrating, too, because there are many conflicting opinions about what causes hip flexor tightness and what to do about it.

Fortunately, you can likely get relief by following the simple plan outlined above:

- Do one stretch several times per day for several days, and note if it helped.

- Do the same with the rest of the stretches and keep doing those that helped.

- Do exercises that strengthen your hip flexors.

What’s your take on the hip flexors? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- McCurdy K, Conner C. Unilateral support resistance training incorporating the hip and knee. Strength Cond J. 2003;25(2):45-51. doi:10.1519/00126548-200304000-00007

- Reiman MP, Lorenz DS. Integration of strength and conditioning principles into a rehabilitation program. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011;6(3):241-253. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21904701. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- Chen SM, Liu MF, Cook J, Bass S, Lo SK. Sedentary lifestyle as a risk factor for low back pain: A systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82(7):797-806. doi:10.1007/s00420-009-0410-0

- Lis AM, Black KM, Korn H, Nordin M. Association between sitting and occupational LBP. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(2):283-298. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0143-7

- Hartvigsen J, Leboeuf-Yde C, Lings S, Corder EH. Review Article: Is sitting-while-at-work associated with low back pain? A systematic, critical literature review. Scand J Public Health. 2000;28(3):230-239. doi:10.1177/14034948000280030201

- Bakker EWP, Verhagen AP, Van Trijffel E, Lucas C, Koes BW. Spinal mechanical load as a risk factor for low back pain: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(8). doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318195b257

- Arab AM, Nourbakhsh MR. The relationship between hip abductor muscle strength and iliotibial band tightness in individuals with low back pain. Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-18-1

- Casartelli NC, Leunig M, Item-Glatthorn JF, Lepers R, Maffiuletti NA. Hip flexor muscle fatigue in patients with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Int Orthop. 2012;36(5):967-973. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1385-5

- Andersen LL, Andersen CH, Zebis MK, Nielsen PK, Søgaard K, Sjøgaard G. Effect of physical training on function of chronically painful muscles: A randomized controlled trial. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105(6):1796-1801. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91057.2008

- Kjær M. Role of Extracellular Matrix in Adaptation of Tendon and Skeletal Muscle to Mechanical Loading. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(2):649-698. doi:10.1152/physrev.00031.2003