Many weightlifters struggle to develop their lower chest.

To make matters worse, the evidence-based fitness community claims there’s not much they can do about it.

There are many excellent exercises for developing your pecs as a whole, they say, but none of them target the lower part in particular. The best you can do is stick to the same old chest exercises and hope the bottom of your pecs fills out in time.

Is this true?

Or can you train your lower chest specifically?

And if so, what are the best lower chest exercises?

And how do you arrange these exercises into an effective lower chest workout?

Get evidence-based answers to all these questions and more in this article.

Chest Anatomy

The pectoralis majors, or “pecs,” are the large, fan-shaped muscles of the chest.

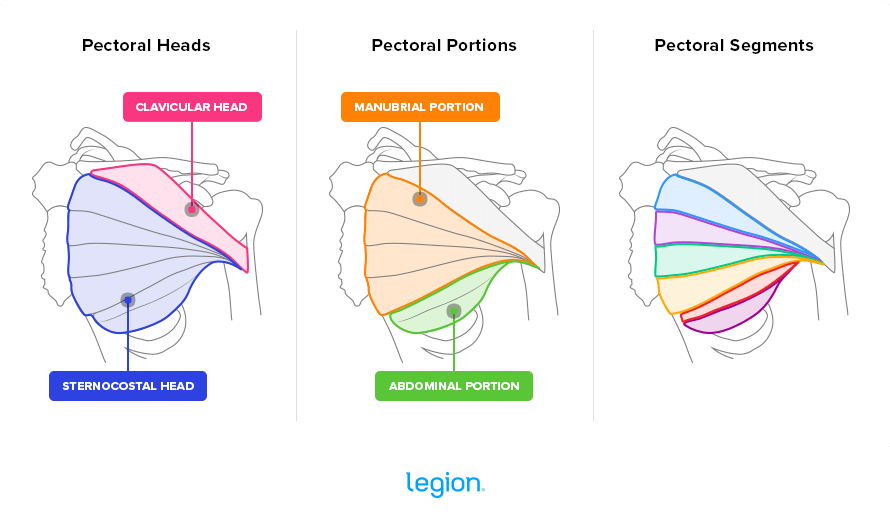

They have two main sections or “heads:” the clavicular head, or “upper pec,” and the sternocostal head, or “mid and lower pec.”

Many scientists also divide the sternocostal head into two subsections: the manubrial portion, which makes up the bulk of the sternocostal head, and the abdominal portion, which is the small region at the bottom of the pec.

(Some scientists refer to the abdominal portion as the third head of the pecs, though not all agree.)

You can further divide these subsections into 6-to-7 segments. Here’s how all this looks on your body:

It’s worth mentioning that while most people’s pecs will look similar to the diagram above, variations between people are common. According to some research, the pecs are six times more likely than any other muscle group to look and connect to your skeleton atypically.

This is significant because it means that for you, any of the aforementioned heads, sections, and segments may be larger or smaller or more or less numerous than average (for example, some people have an “extra” pectoral head called a chondrocoracoideus).

This means your pecs may look significantly different from the next person’s, and depending on your anatomy, there may not be much you can do to alter their appearance appreciably.

Can You Train Your Lower Chest?

Received gym wisdom states that to train your upper pecs, you need to emphasize incline pressing; to train your entire chest, you should prioritize flat pressing; and to maximize lower chest development, you want to focus on decline pressing.

There’s some truth to this.

Studies show that the incline bench press is best for training your upper pecs and that the flat bench press is highly effective at training your pecs as a whole.

This logic collapses when it comes to the decline bench press, though.

For example, in one study conducted by scientists at The University of Queensland, researchers found that the flat and decline bench press were similarly effective at training the sternocostal head of the pecs, including the abdominal portion.

Another study published in the European Journal of Sports Science found that the decline bench press is no more effective at activating the lower portion of the sternocostal head of the pecs than the flat bench press.

As such, most evidence-based fitness folk say there’s no way to train your lower chest. That is, they say you can train the sternocostal head of your pecs, which includes the lower segments, but there’s no way to “isolate” the abdominal portion, which means there’s no way to bias your training to developing the lower pecs if that’s the part that’s lagging.

Why, then, do many weightlifters believe that the decline bench press preferentially trains the lower chest?

Anecdotal evidence aside (many claim they “feel” their lower pecs working more during the decline bench press), it likely stems from our knowledge of how the pecs function.

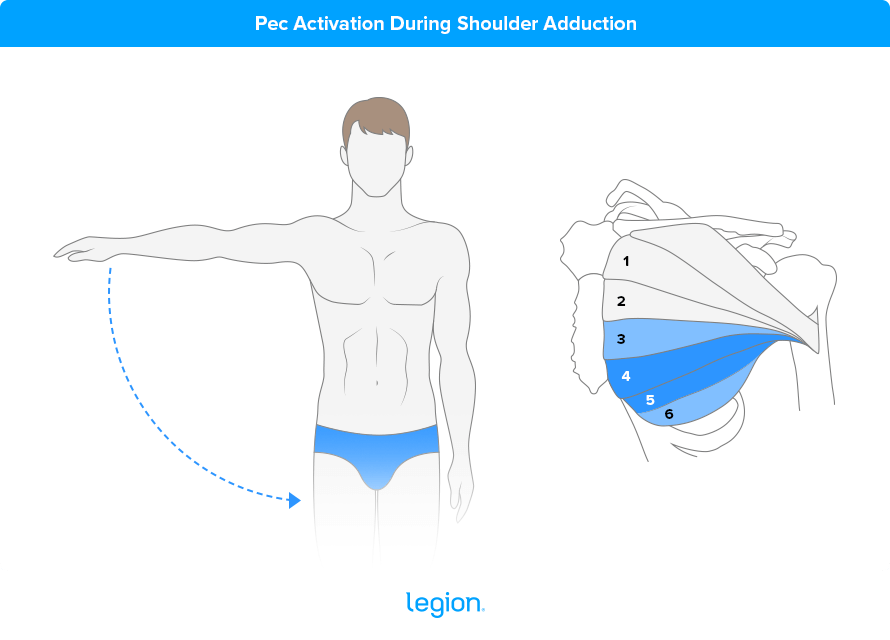

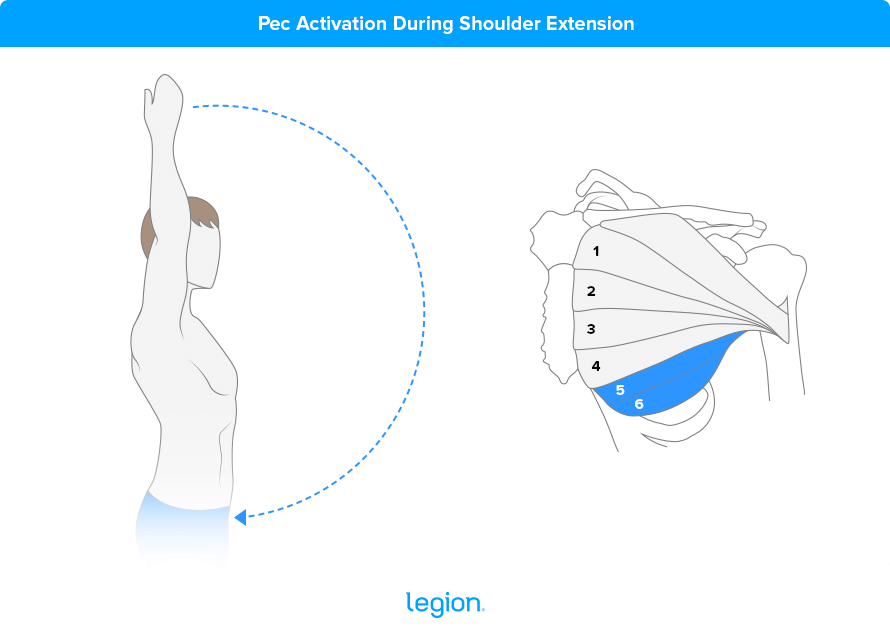

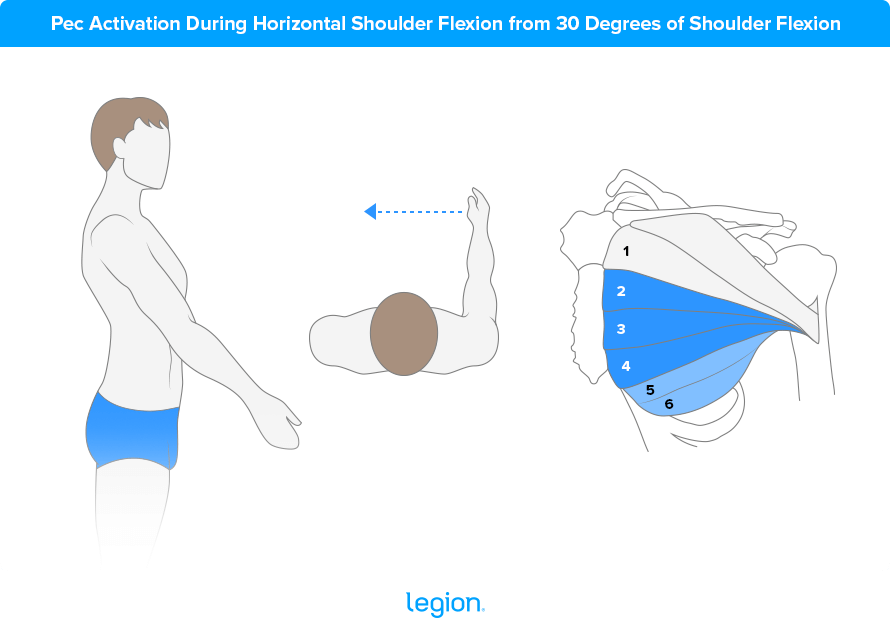

The sternocostal head of the pecs performs horizontal shoulder adduction (bringing your arm toward the midline of your body). However, not all segments of the pecs contribute equally to this action; single segments act with a degree of independence depending on the demands of the movement.

In other words, how you move your arms and shoulders changes which segments of your pecs perform the lion’s share of the work.

A neat example of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at the University of Wollongong, in which experienced weightlifters performed a series of movements against varying resistance while researchers measured muscle activation in each segment of their pecs.

They found that the lower segments of the pecs (the abdominal portion) were most active when the weightlifters performed shoulder adduction (pulling your upper arms to your sides), shoulder extension (bringing your arms in an arc from overhead to your sides), and horizontal shoulder flexion from 30 degrees of shoulder flexion (moving as you would in the decline bench press, basically).

Here are some illustrations adapted from the study showing each of these movements and how they activated the pecs. Dark blue denotes high activation, light blue denotes moderate activation, and gray denotes low activation:

While it’s tempting to take this as evidence that doing exercises that mimic these movements will help grow your lower pecs, it would be injudicious to do so. There are too many caveats for that.

For instance, this study only measured muscle activation. And while muscle activation is necessary for building muscle—no activation always means no growth—it isn’t perfect for gauging growth.

Furthermore, this wasn’t a weightlifting study. That is, it didn’t look at how different exercises train the pecs and how much muscle growth occurred as a result.

Rather, it looked at how various movements change muscle activation in the pecs. And that makes it difficult to know whether we can apply the findings to exercises like the decline bench press.

This point is even more pertinent given that when studies actually compare the flat and decline bench press, the results show they’re comparable lower-pec builders.

Perhaps the most sensible way to interpret these results is this: there’s a decent theoretical argument that exercises involving shoulder adduction, shoulder extension, and decline pressing movements will emphasize the lower pecs.

Thus, if your mid and upper chest are well-developed, but your lower pecs are lagging, it may make sense to do exercises that theoretically “target” your lower chest. While there’s no guarantee you’ll get the results you want, taking this tack probably won’t harm your mid-to-lower-pec development, making it a low-risk, potentially high-reward strategy for building the bottom of your chest.

(Bear in mind, however, that making lower chest exercises the focus of your training may stymie shoulder and upper chest growth since flat and incline pressing exercises tend to be superior at training these muscle groups.)

The Best Lower Chest Exercises

Based on what we’ve learned about how to work your lower chest, here are 10 of the best exercises for lower chest.

1. Bench Press

The bench press is the king of chest exercises because it trains your upper, mid, and lower pecs to a high degree and allows you to lift heavy weights safely, which is vital for gaining muscle and strength.

2. Dip

The dip is an excellent exercise for training your upper-body pushing muscles, including your pecs. What’s more, performing it with a slight forward lean puts your arms at about the right angle to emphasize your lower pecs.

3. Dumbbell Bench Press

The dumbbell bench press trains your pecs similarly to the barbell bench press, making it one of the most effective lower chest dumbbell exercises you can do.

4. Decline Bench Press

The decline bench press places your arms into ~30 degrees of shoulder flexion, which may help you emphasize the lower pecs more than other pressing exercises.

5. Decline Dumbbell Bench Press

The decline dumbbell bench press is very similar to the decline bench press, which means it’s about as effective at training your lower pecs. What makes it slightly different is that it involves dumbbells instead of a barbell.

The benefits of this are that the decline dumbbell bench press has a slightly longer range of motion, which is important for muscle and strength gain, and it trains each side of your body independently, which helps you identify and even out muscle imbalances.

The downside, however, is that it can be challenging to get into the decline position while holding dumbbells, especially as the weights get heavy.

6. Dumbbell Pullover

The dumbbell pullover trains shoulder flexion, which means it may be well-suited to training your lower pecs. Furthermore, it trains your pecs in a stretched position, which is generally beneficial for muscle growth.

7. Cable Pullover

The cable pullover trains your upper body similarly to the dumbbell pullover, making it another good option for training your lower pecs. The main benefit of the cable pullover is that it uses a cable, which keeps constant tension on your pecs throughout each rep.

8. Incline Push-up

The incline push-up (or “lower chest push-up”) is one of the most effective push-ups for lower chest because, unlike other push-up variations, it places your arms into ~30 degrees of shoulder flexion, which may increase the amount your lower pecs contribute to the exercise.

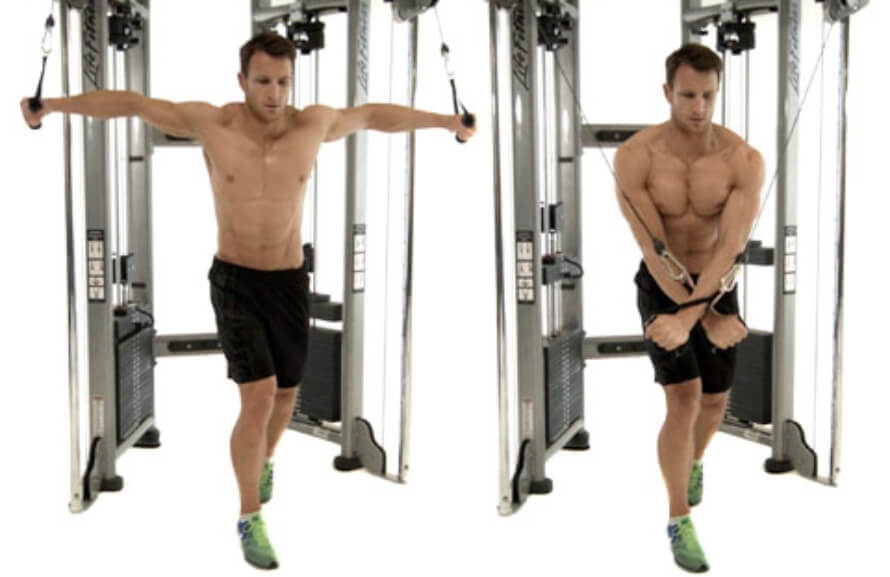

9. High-to-Low Cable Fly

The high-to-low cable fly (often referred to as the “lower chest cable fly”) trains shoulder adduction, which means it might emphasize the lower pec more than the regular cable fly. To maximize lower pec involvement, bring your hands together (or slightly past each other) 6-to-8 inches in front of your thighs rather than in front of your torso or chest.

10. Decline Dumbbell Fly

The decline dumbbell fly (or “lower chest fly”) is an excellent lower chest dumbbell exercise for isolating the pecs. The main benefit is that it trains your pecs when deeply stretched, which is important for maximizing muscle growth.

The Best Lower Chest Workout

Most workouts for lower chest that you find online focus too much on high-rep, pump-style training and recommend doing too many isolation exercises for the lower pecs.

This is a mistake.

If you want to maximize lower-pec development, you need to emphasize compound weightlifting that trains your entire chest (and may emphasize your lower pecs) and allows you to lift heavy weights safely and get stronger over time.

With that in mind, here’s what I recommend:

Bench Press: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Dip: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Dumbbell Pullover: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

High-to-Low Cable Fly: 3 sets of 8-to-10 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

And if you like the look of this workout and want a program based on similar principles to train your entire body, check out Mike Matthews’ fitness books for men, Bigger Leaner Stronger.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger is right for you or if another strength training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Scientific References +

- Solari, F., & Burns, B. (2022). Anatomy, Thorax, Pectoralis Major Major. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525991/

- Sanchez, E. R., Howland, N., Kaltwasser, K., & Moliver, C. L. (2014). Anatomy of the Sternal Origin of the Pectoralis Major: Implications for Subpectoral Augmentation. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 34(8), 1179–1184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X14546370

- Wolfe, S. W., Wickiewicz, T. L., Cavanaugh, J. T., & Shirley, P. (1992). Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 20(5), 587–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354659202000517

- Fung, L., Wong, B., Ravichandiran, K., Agur, A., Rindlisbacher, T., & Elmaraghy, A. (2009). Three-dimensional study of pectoralis major muscle and tendon architecture. Clinical Anatomy (New York, N.Y.), 22(4), 500–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/CA.20784

- Burley, H. E. K., Haładaj, R., Olewnik, Ł., Georgiev, G. P., Iwanaga, J., & Tubbs, R. S. (2021). The clinical anatomy of variations of the pectoralis minor. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy, 43(5), 645–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00276-021-02703-Y/METRICS

- Haładaj, R., Wysiadecki, G., Clarke, E., Polguj, M., & Topol, M. (2019). Anatomical Variations of the Pectoralis Major Muscle: Notes on Their Impact on Pectoral Nerve Innervation Patterns and Discussion on Their Clinical Relevance. BioMed Research International, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6212039

- Burley, H., Georgiev, G. P., Iwanaga, J., Dumont, A. S., & Tubbs, R. S. (2020). An unusual finding of the pectoralis major muscle: decussation of sternal fibers across the midline. Anatomy & Cell Biology, 53(4), 505. https://doi.org/10.5115/ACB.20.058

- Venieratos, D., Samolis, A., Piagkou, M., Douvetzemis, S., Kourotzoglou, A., & Natsis, K. (2017). The chondrocoracoideus muscle: A rare anatomical variant of the pectoral area. Acta Medica Academica, 46(2), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.5644/ama2006-124.200

- Zielinska, N., Ruzik, K., Georgiev, G. P., Dimitrova, I. N., Tubbs, R. S., & Olewnik, Ł. (2022). A new variety of chondrocoracoideus muscle, or an additional head of pectoralis major muscle. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy, 44(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00276-022-02887-X/FIGURES/2

- Trebs, A. A., Brandenburg, J. P., & Pitney, W. A. (2010). An electromyography analysis of 3 muscles surrounding the shoulder joint during the performance of a chest press exercise at several angles. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(7), 1925–1930. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181DDFAE7

- Saeterbakken, A. H., Mo, D. A., Scott, S., & Andersen, V. (2017). The Effects of Bench Press Variations in Competitive Athletes on Muscle Activity and Performance. Journal of Human Kinetics, 57(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1515/HUKIN-2017-0047

- Roy, X., Arseneault, K., & Sercia, P. (2021). The Effect of 12 variations of the bench press exercise on the EMG activity of three heads of the pectoralis major. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.47206/IJSC.V1I1.39

- Barnett, C., Kippers, V., & Turner, P. (n.d.). Effects of Variations of the Bench Press Exercise on the EMG... : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/1995/11000/Effects_of_Variations_of_the_Bench_Press_Exercise.3.aspx

- Lauver, J. D., Cayot, T. E., & Scheuermann, B. W. (2016). Influence of bench angle on upper extremity muscular activation during bench press exercise. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(3), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2015.1022605

- Lulic-Kuryllo, T., Negro, F., Jiang, N., & Dickerson, C. R. (2022). Differential regional pectoralis major activation indicates functional diversity in healthy females. Journal of Biomechanics, 133, 110966. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBIOMECH.2022.110966

- Brown, J. M. M., Wickham, J. B., McAndrew, D. J., & Huang, X. F. (2007). Muscles within muscles: Coordination of 19 muscle segments within three shoulder muscles during isometric motor tasks. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology : Official Journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology, 17(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JELEKIN.2005.10.007

- Paton, M. E., & Brown, J. M. M. (1994). An electromyographic analysis of functional differentiation in human pectoralis major muscle. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology : Official Journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology, 4(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/1050-6411(94)90017-5

- Vigotsky, A. D., Beardsley, C., Contreras, B., Steele, J., Ogborn, D., & Phillips, S. M. (2017). Greater electromyographic responses do not imply greater motor unit recruitment and “hypertrophic potential” cannot be inferred. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(1), E1–E2. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001249

- Oranchuk, D. J., Storey, A. G., Nelson, A. R., & Cronin, J. B. (2019). Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 29(4), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.13375

- Maeo, S., Wu, Y., Huang, M., Sakurai, H., Kusagawa, Y., Sugiyama, T., Kanehisa, H., & Isaka, T. (2022). Triceps brachii hypertrophy is substantially greater after elbow extension training performed in the overhead versus neutral arm position. European Journal of Sport Science. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2022.2100279