It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn why you should basically always lift weights as explosively as possible, if DNA diets are better than regular diets for weight loss, and how naps boost performance.

When weightlifting, focus on lifting explosively rather than contracting particular muscles.

Source: “Influence of Different Attentional Focus on EMG Amplitude and Contraction Duration During the Bench Press at Different Speeds” published on August 10, 2017 in Journal of Sports Sciences.

An old bodybuilding axiom states that you should lift weights in a slow, controlled fashion and focus intently on the muscle you’re trying to train. If you want to burnish your biceps, for example, then you’d slowly raise and lower the weight as you curl it, thinking hard about contracting your biceps.

Some even claim that lifting quickly can hurt your progress, since it causes other muscles to “take over” and “robs” your target muscle group of gains.

While some research suggests that “internal cues” (focusing on a body part during exercise) can increase muscle activation in the muscle you’re trying to train, this isn’t necessarily the optimal way to direct your attention while training. In other words, there’s no doubt that it’s better to train focused than foggy, but it’s still an open question as to whether you should focus on your muscles (like old school bodybuilders claim) or something else, like lifting the weight explosively.

The argument for the latter is this: When you try to lift a weight explosively, your central nervous system (CNS) calls on all the available muscle fibers—in the target muscle and any others that are well-placed to assist—to maximize force and power output.

And this makes one wonder . . . Wouldn’t lifting explosively train all the fibers in the target muscle, and many more besides, better than slow, focused reps? And what would happen if you layered internal cues on top of explosive lifting? Would muscle activation increase more than using either technique in isolation? (For instance, thinking about using your pecs to drive the bar upward as fast as possible while bench pressing.)

These are the questions scientists at the National Research Centre for the Working Environment wanted to answer with this study.

The researchers had 18 men with at least 1 year of training experience, and an average bench press one-rep max of ~227 pounds report to the lab for a workout. During the workout, the participants did 6 sets of 3 reps with 50% of their one-rep max on the bench press.

For three sets, the researchers told the participants to use a 2-second eccentric (lowering phase) and a 2-second concentric (lifting phase) for each rep (slow reps). In the other three sets, the researchers told the participants to use a 2-second eccentric and press the bar as quickly as possible (explosive reps).

In both “speed conditions”—slow reps and explosive reps—the participants did one set without using internal cues (“lift the barbell in a regular way”), one set using internal cues for the pecs (“try to focus on using your chest muscles only”), and one set using internal cues for the triceps (“try to focus on using your triceps muscles only”).

The results showed that using internal cues significantly increased muscle activation (+6% for the pecs and +4% for the triceps) during the reps performed with a controlled cadence, as you might expect.

What was more impressive were the results from the explosive sets.

They showed that using internal cues while lifting explosively didn’t increase muscle activation in the target muscles compared to lifting explosively without internal cues. However, muscle activation in the pecs and triceps was significantly higher in the explosive sets than in the controlled sets, whether the participants used internal cues or not.

In other words, lifting explosively without any particular cues in mind causes higher muscle activation than lifting slowly and concentrating on particular muscles.

As a general rule, then, you want to lift weights as fast as possible while maintaining good form and control of the weight. This usually means lowering the weight with control, then raising the weight as fast as possible.

Keep in mind that attempting to move the weight as fast as possible doesn’t mean the weight will move quickly. If you’re lifting heavy weights, the weight will still appear to move slowly to the naked eye (a second or more per rep is normal), even when you try to lift explosively. In other words, the intention to move the weight as fast as possible is more important than the actual speed of the weight.

Of course, there are exceptions to this guideline. For instance, it’s helpful to perform your reps at a slower cadence when learning a new exercise, until you ingrain proper form. If you’re working around an injury or returning to the gym after recovering from one, you may also want to slow down your reps a tad to ensure they don’t cause any pain.

Finally, I think an ideal solution (and what I do personally) would be to combine external cues, which direct your attention toward how your movements impact an object in your environment, with a focus on lifting explosively.

While the researchers didn’t compare external cues with internal ones in this study, just about every scientific study on this topic has found external cues are superior to internal ones. For example, when squatting you could focus on ramming the bar into the ceiling (external cue) as fast as possible (explosively).

And if you want a complete list of my favorite weightlifting cues for the squat, bench press, and deadlift, check out this article.

TL;DR: Lift weights as explosively as possible if you want to activate your muscles as much as possible (don’t bother focusing intently on a particular muscle group).

“DNA diets” work no better than regular diets for weight loss.

Source: “Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion: The DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial” published on February 20, 2018 in Journal of the American Medical Association.

The idea behind DNA-based diets is that you spit in a tube and mail your slobber to a testing company, which then sifts your spit and looks for genetic markers that supposedly dictate your dietary needs.

Generally, you’ll get a list of what foods you should or shouldn’t eat to lose weight and sometimes macronutrient and food timing guidelines as well. According to these companies, as long as you eat foods that are compatible with your unique genotype (DNA profile), then you should be able to lose weight with ease.

Eat foods that aren’t coincident with your DNA profile, though, and getting the body you want will feel like swimming upstream.

Is any of that true, though?

That’s what scientists at Stanford University Medical School wanted to find out when they divided 609 young and middle-aged obese men and women into two groups: One group followed a high-carb, low-fat diet and the other followed a low-carb, high-fat diet. Both diets were made up of whole, minimally processed foods and put the participants in a calorie deficit for the entire study.

For the first 2 months of the study, the researchers instructed the participants to consume no more than 20 grams of fat (in the high-carb group) or carbs (in the low-carb group). Since they would be following these diets for a whole year, the researchers allowed them to increase their fat or carb intake slightly, but encouraged them to hew as closely to the original dietary guideline as possible.

This study wasn’t just about low-carb versus high-carb diets, though.

The two main questions the researchers wanted to answer were:

- Can you predict the best weight loss diet for people based on their DNA?

- Can you predict the best weight loss diet for people based on their insulin sensitivity?

There are a handful of genes that scientists think may make some people more efficient at processing carbs, and others more efficient at processing fat, which may influence how effectively people can lose weight while following different diets.

In this study, the researchers tested each participant’s DNA and recorded whether people fell into the “high-carb,” “low-carb,” or “neutral” genotype based on their results.

The researchers also measured everyone’s insulin sensitivity, which is partly determined by your DNA. They did this because many people claim that those who are more insulin sensitive can lose weight while eating a high-carb diet, whereas those who are less insulin sensitive will lose more weight if they follow a low-carb diet.

Based on the results of the insulin sensitivity test, the researchers categorized everyone as having either low-, moderate-, or high-insulin sensitivity.

Finally, the researchers made sure that people from every DNA- and insulin-sensitivity-based group were assigned to both the low- and high-carb diet groups.

The result?

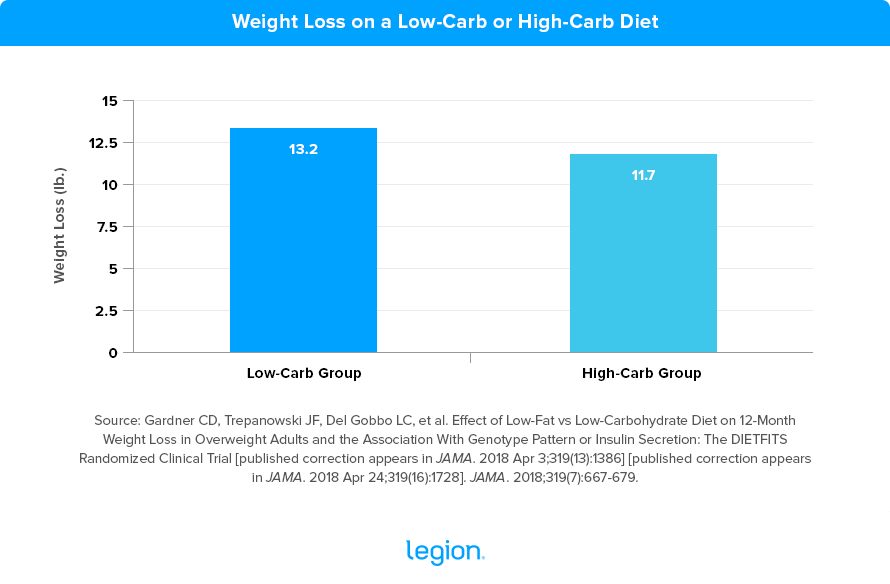

People’s genetic makeup, insulin sensitivity, and macronutrient intake had essentially zero impact on their ability to lose weight. Here’s what the results looked like after a year:

The only difference between the groups was that the low-carb group experienced a larger rise in LDL (“bad”) and HDL (“good”) cholesterol than the high-carb group, and a larger decrease in triglycerides, which is a sign of better cardiovascular health. However, the differences were too small to make any difference to health or disease risk.

This study blasts a hole in the longstanding idea that people who are more insulin sensitive can “get away” with eating more carbs while dieting, whereas people who are less sensitive to insulin should always go low carb, and it also casts doubt on the idea that fine-tuning our diets to our DNA will help us lose weight faster.

There’s no question that some people prefer to eat more or fewer carbs or certain foods over others, and this can help them stick to their diet better and thus lose more weight, but this has more to do with taste and temperament rather than inborn genetic hardwiring.

Oh, and can you guess what best predicted the participant’s ability to lose weight?

I’ll give you a hint: it rhymes with “salaries.”

Awoooga! You guessed it—calories!

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about which diet you should follow to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: Following a diet based on your genetic makeup or insulin sensitivity won’t help you lose fat. Instead, focus on eating the right number of calories for your goals, sufficient protein, and a balance of carbs and fat that suits your druthers.

Naps make you a better athlete.

Source: “Physiological response and physical performance after 40 min and 90 min daytime nap opportunities” published on May 25, 2022 in Research in Sports Medicine.

The best way to maintain a healthy sleep schedule is to go to bed at roughly the same time every night, wake up at roughly the same time (ideally, without an alarm), and minimize stimulating activities and surroundings before bed.

A fine ideal to shoot for, but most of us contravene these rules occasionally, leaving us feeling done in the next day. The body is a fickle beast, too, and regardless of how perfect your sleep hygiene is, your energy levels will sag inexplicably from time to time. This is particularly true in the early afternoon, when most people experience a “post-lunch” dip in energy levels regardless of how well they slept the night before.

You can always Big Tough Frogman your way through, but if you want to make the most of your workouts, this study suggests that siestas are a better solution.

The researchers had 14 amateur male soccer, rugby, and handball players report to the lab on 3 occasions with at least 3 days between each visit. During each visit, they completed one of three “nap conditions:” a 90-minute nap, a 40-minute nap, or no nap. After waiting an hour to shake off the cobwebs, the athletes then performed two exercise tests:

- A quad strength test using a machine that was similar to a leg extension machine

- A shuttle run test that involved running a series of sprints

The night before each visit, the participants slept wearing an activity tracker. This allowed the researchers to see that the participants slept normally, which ensured the study’s results weren’t distorted by atypical bedtime behavior. For example, they could be sure the participants didn’t go to bed unusually late or get less sleep than normal, both of which might change the outcomes of the study.

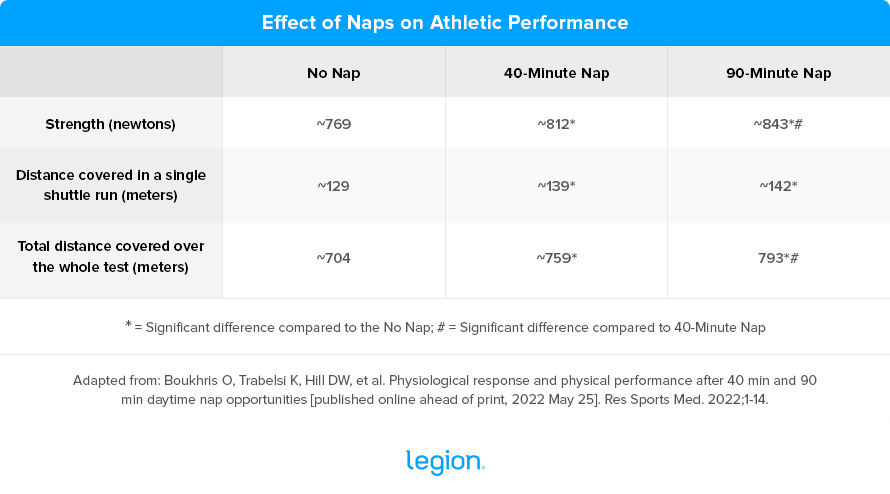

The results showed that when the athletes napped, they were consistently and significantly stronger, faster, and more agile than when they didn’t.

Here’s how the different “nap conditions” compared:

After napping, participants also reported feeling less tense, depressed, angry, tired, sore, and confused and more energetic and focused. They also thought the workouts felt easier (they had a lower RPE).

In every case, napping was better than not napping. Napping for 90 minutes was better than napping for 40 minutes, although the benefits began to taper off. In other words, napping for 40 minutes gives you about 80+% of the benefits of napping for 90 minutes, making it a more time efficient option for most people.

This study stands alongside several others that show napping, whether you’ve had a bad night’s sleep the night before or not, has a beneficial effect on your athletic performance and overall mental state and mood.

Obviously, not everyone has the chance to take 40 winks before they train. If the opportunity presents itself, or you have an important workout, rep-max test, or big game late in the day, sneaking a snooze beforehand will help you perform at your best.

If you want to know more about the benefits of napping, as well as advice on how to ensure naps help rather than hinder your performance, check out this article:

Can Napping Help You Get Fitter Faster? What Science Says

(And if you’re interested in a 100% natural sleep supplement that helps you fall asleep faster, stay asleep longer, and wake up feeling more rested, try Lunar).

TL;DR: Taking a 40-minute nap before you work out improves your performance, mood, energy, focus, and recovery, and you can get slightly greater benefits with a 90-minute nap.