It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn whether having a “slow” metabolism hinders long-term weight maintenance, whether you should use drop sets to gain muscle and strength, and how “body positivity” can contribute to obesity.

Having a “slow metabolism” isn’t why people regain weight.

Source: “Physiological Predictors of Weight Regain at 1-Year Follow-Up in Weight-Reduced Adults with Obesity” published on April 20, 2019 in Obesity (Silver Spring).

Many people blame their metabolism for why they can’t keep weight off.

That is, they periodically diet with some success, but fail to stay leaner for long. And when they regain the weight they lost (or get heavier), they claim it’s because their metabolism grinds to a halt when they diet.

Some scientists think they have a point, too.

While the scientific community still doesn’t fully understand why weight regain is so common, many researchers believe that metabolic slowdown and increased hunger during dieting play a significant role.

Scientists at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology put these ideas to the proof in this study.

They had 36 obese people follow a crash diet for 8 weeks, during which the men and women could eat 660 and 550 calories daily, respectively.

For the following 5 weeks (up to week 13 of the experiment), the dieters worked with a dietician to wean themselves off the crash diet and onto a regular diet designed to help them maintain their new, lower weight.

The dieters then followed their new diet for a year. During this time, they continued to work with a dietician to adjust their calories and macros as necessary, and regularly attended coaching sessions where they learned how diet, exercise, and their psychological state affect weight maintenance.

The results showed that after week 13, the dieters had lost an average of ~45 lb each. Between week 13 and 1 year, most dieters (30 out of 36) were at least 10% lighter than they had been at the beginning of the experiment.

After losing weight, the dieters burned significantly fewer calories at rest and while moving than they did at the beginning of the experiment. They also had higher levels of the hormone ghrelin (which stimulates appetite) and generally felt more hungry.

However, none of these changes correlated with weight loss or regain.

In other words, people’s metabolic rate slowed and they felt more hungry, but this didn’t stop them losing weight, or make them more likely to regain weight.

This should come as welcome news to anyone who thinks their “slow” metabolism thwarts their chances of long-term weight loss. According to these results, it doesn’t.

Instead, this study suggests that weight maintenance is more of a mental and behavioral challenge. With the right guidance, though, anyone can lose weight and keep it off.

If you want to learn the simple science of sustainable weight loss for yourself and get a diet and exercise plan that’ll help you lose weight, build muscle, and get healthier, check out my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

Or, if you’d prefer an expert to give you everything you need to lose weight for good, including custom diet and training plans, willpower and mindset coaching, emotional encouragement, accountability, and more, contact Legion’s VIP one-on-one coaching service to set up a free consultation. Click here to check it out.

TL;DR: Most people regain weight after dieting because they don’t make sustainable changes to their diet, activity levels, and behavior, not because their metabolism slows.

Drop sets may help you gain muscle and strength.

Source: “Muscular Adaptations in Drop Set vs. Traditional Training: A Meta-Analysis” published on November 28, 2022 in International Journal of Strength and Conditioning.

Many bodybuilders swear by drop sets.

According to them, training to failure, then “dropping” the weight by 10-to-20% and continuing the set until you fail again, boosts muscle growth (mainly by increasing “time under tension” and giving you a pump).

Many in the evidence-based fitness crowd disagree.

That’s because drop sets involve lifting progressively lighter weights and taking little to no rest between drop sets, which is counter to the scientific consensus on the best way to build muscle.

Who’s right in this training tête-à-tête?

A meta-analysis conducted by scientists at CUNY Lehman College offers some insight.

The researchers analyzed the results from 5 studies and found that you gain about as much muscle and strength from drop sets as you do from traditional sets.

Wait . . . wut?!

The bodybuilders were right?

Not quite. These results show that drop sets don’t have unique muscle-building benefits. They may cause muscle growth, but they’re no more effective than regular training.

There are some important caveats to consider, too.

First, this meta-analysis only included five studies, which is very small for research of this kind. What’s more, each of the five included studies were small—4 out of 5 included fewer than 30 participants.

And because the authors had only a small amount of research to work with, they couldn’t run deeper tests on the data to investigate how factors such as training experience and volume and intensity might affect the results.

In other words, while the data seemed to suggest that drop sets and traditional training are equally effective for gaining muscle and strength, the analysis was too basic to draw firm conclusions.

Second, the studies included in this meta-analysis only investigated how drop sets affected the biceps, triceps, and quads. As such, we can’t say whether drop sets would keep pace with traditional training for all muscle groups.

Third, none of the studies had the participants lift more than 80% of their one-rep max. Given that lifting heavy weights is generally superior to lifting light weights for gaining muscle and strength, there’s a good chance that the results would have favored traditional sets if the studies had included heavier training.

And with these in mind, it’s probably too soon to say drop sets and traditional sets are equally effective for gaining muscle and strength.

A more reasonable reading of this research is that drop sets seem to be a viable way to train, especially if you’re time-pressed, since they allow you to do more training in less time.

That said, I’d still recommend using drop sets sparingly, even if you’re in a rush. As a general rule, only use them for your final set of isolation exercises.

For example, if your workout calls for 3 sets of the triceps pushdown, do your first 2 sets as normal, then take your third set to within a rep of failure, reduce the weight by 10-to-20% and continue your set until you can’t do another rep with proper form. (Used in this way, they’re similar to rest-pause sets).

TL;DR: Drop sets can help you gain muscle and strength, but the research still doesn’t convincingly show they’re as good as traditional sets.

One reason people struggle to lose fat? Most people underestimate how big they really are.

Source: “Normalization of Plus Size and the Danger of Unseen Overweight and Obesity in England” published on June 22, 2018 in Obesity (Silver Spring).

The “body positivity movement” has gained an enormous following over the past decade.

What draws people to it is the promise that you’ll learn to unconditionally love your body, regardless of its size, shape, and appearance, and in doing so, boost your mental well-being (and possibly lose weight by reducing stress eating, some say).

And while many people view this as a salubrious development, others aren’t convinced.

For its detractors, body positivity’s biggest flaw is that it ignores the physical health risks of being overweight.

In other words, it normalizes an objectively unhealthy behavior and sets others up for the same fate by lowering our collective societal standards for health and fitness.

For example, studies show that when obesity is commonplace, people tend to underestimate their body weight. This makes them less driven to lose weight, which may exacerbate the obesity epidemic over the long term. (I wonder what René Girard would think of this.)

A study by scientists at the University of East Anglia elegantly illustrates this point.

The researchers looked back at the Health Survey for England between 1997 and 2015 and reviewed 23,459 overweight and obese people’s answers to the following question:

Given your age and height, would you say that you are . . .

- About the right weight

- Too heavy

- Too light

- Not sure

They found that ~39% of male and ~17% of female respondents perceived their weight as about right (remember, these people were objectively either overweight or obese according to their BMI).

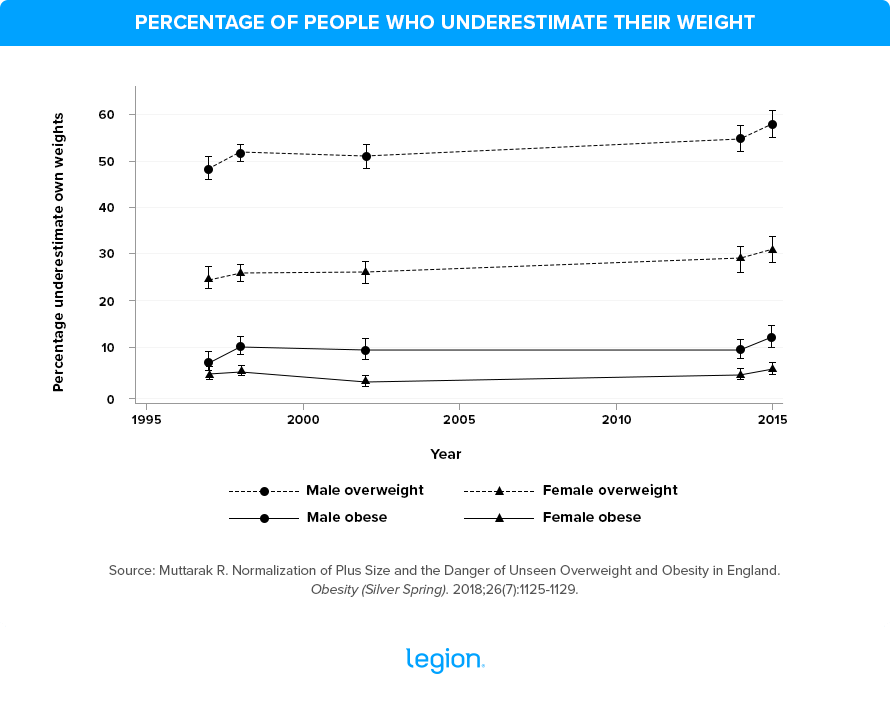

Moreover, the number of people that underestimated their weight increased over time, from ~48% to ~58% in men and ~25% to ~31% in women between 1997 and 2015. Almost three-quarters (~73%) of those surveyed also reported their health as good or very good.

This graph summarizes some of these results:

Since men were more likely than women to underestimate their weight, they were also less likely to try to lose weight (~48% vs. ~71%).

Overweight people were also more likely to underestimate their weight than obese people (~41% vs. ~8%). As such, only about half of overweight individuals were trying to lose weight compared with over two-thirds of those with obesity.

People were ~85% less likely to attempt to lose weight if they underestimated their weight, too.

In sum, these results suggest that the prevalence of obesity is changing people’s perception of body weight, such that they find it hard to accurately evaluate their weight. This means that overweight and obese people are more likely to consider themselves leaner and healthier than they really are and, thus, less likely to try to better their body composition.

And this is terrible news for obesity rates.

How can you avoid becoming an NPC about your BMI?

You could follow the steps in this article and use this calculator to accurately estimate your body fat percentage, but if you’re reading this article, you probably don’t need to do any of that.

Just look in the mirror. Happy with what you see? Yes? Then carry on. No?

Excellent! Accepting reality is the first step to building your best body ever.

If you’d like some help with that, I suggest starting with my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger is right for you or if another strength training program and diet plan might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz and the Legion Diet Quiz and in just a couple of minutes, you’ll know the the perfect strength training program and diet for you.)

TL;DR: Many overweight and obese people think they’re leaner than they are because they’re surrounded by other overweight and obese people, which makes them complacent about losing weight.

Scientific References +

- Nymo, S., Coutinho, S. R., Rehfeld, J. F., Truby, H., Kulseng, B., & Martins, C. (2019). Physiological Predictors of Weight Regain at 1-Year Follow-Up in Weight-Reduced Adults with Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 27(6), 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/OBY.22476

- Stunkard, A., & Mclaren Hume, M. (1959). The Results of Treatment for Obesity: A Review of the Literature and Report of a Series. A.M.A. Archives of Internal Medicine, 103(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHINTE.1959.00270010085011

- Leibel, R. L., Rosenbaum, M., & Hirsch, J. (1995). Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. The New England Journal of Medicine, 332(10), 621–628. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199503093321001

- Ochner, C. N., Barrios, D. M., Lee, C. D., & Pi-Sunyer, F. X. (2013). Biological mechanisms that promote weight regain following weight loss in obese humans. Physiology & Behavior, 120, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2013.07.009

- Sumithran, P., & Proietto, J. (2013). The defence of body weight: a physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss. Clinical Science (London, England : 1979), 124(4), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20120223

- Nymo, S., Coutinho, S. R., Rehfeld, J. F., Truby, H., Kulseng, B., & Martins, C. (2019). Physiological Predictors of Weight Regain at 1-Year Follow-Up in Weight-Reduced Adults with Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 27(6), 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/OBY.22476

- Coleman, M., Harrison, K., Arias, R., Johnson, E., Grgic, J., Orazem, J., Schoenfeld, B. J., Coleman, M., Harrison, K., Arias, R., & Johnson, E. (2022). Muscular Adaptations in Drop Set vs. Traditional Training: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.47206/IJSC.V2I1.135

- Muttarak, R. (2018). Normalization of Plus Size and the Danger of Unseen Overweight and Obesity in England. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 26(7), 1125–1129. https://doi.org/10.1002/OBY.22204

- Robinson, E. (2017). Overweight but unseen: a review of the underestimation of weight status and a visual normalization theory. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 18(10), 1200–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/OBR.12570

- Fruh, S. M. (2017). Obesity: Risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long‐term weight management. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(Suppl 1), S3. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12510

- Bhaskaran, K., Douglas, I., Forbes, H., dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D. A., & Smeeth, L. (2014). Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. Lancet (London, England), 384(9945), 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8

- Luppino, F. S., De Wit, L. M., Bouvy, P. F., Stijnen, T., Cuijpers, P., Penninx, B. W. J. H., & Zitman, F. G. (2010). Overweight, Obesity, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(3), 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHGENPSYCHIATRY.2010.2

- Robinson, E., & Oldham, M. (2016). Weight status misperceptions among UK adults: the use of self-reported vs. measured BMI. BMC Obesity, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S40608-016-0102-8

- Burke, M. A., Heiland, F. W., & Nadler, C. M. (2010). From “overweight” to “about right”: evidence of a generational shift in body weight norms. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 18(6), 1226–1234. https://doi.org/10.1038/OBY.2009.369

- Robinson, E., & Christiansen, P. (2014). The changing face of obesity: exposure to and acceptance of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 22(5), 1380–1386. https://doi.org/10.1002/OBY.20699