You’ve been training hard and eating right, and you’ve been making gains.

Your stomach is tighter. You’re stronger than ever before. Your friends are starting to make meathead jokes.

But progress has slowed.

It’s getting harder and harder to add weight to the bar and your body isn’t changing like it once was.

What to do?

Well, if you turn to the magazines, you’ll probably conclude that you just have to eat more. “Eat big to get big” right?

Sorta kinda maybe…

Yes, a caloric surplus is conducive to muscle gain, but no, adding a gallon of milk per day to your meal plan isn’t advisable. You’ll gain weight, alright, but too much will be fat.

You need a smarter approach, and rest-pause training can help.

As you’ll see, this simple weightlifting tool can be adapted to any type of workout program, and, unlike most fancy-sounding training tips, it has science on its side. It actually works.

So, in this article, you’re going to learn what rest-pause training is, why it works, and how to do it right so you can get the needle moving again.

Ready?

Let’s start at the top.

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

What Is Rest-Pause Training?

If you’re familiar with my work, you know I’m generally not a fan of training methods that stray from “do heavy compound movements and rest adequately in between sets.”

That’s why my programs don’t have anything in the way of supersets, drop sets, giant sets, and the like, or nontraditional training protocols like super-slow training, super-fast training, and so forth.

Thus, you’d think that I would toss rest-pause sets into the same bucket.

Not so, though. Rest-pause sets get my stamp of approval.

They’re an old school powerlifting method for breaking through plateaus, and research shows that it’s an effective way to increase size and strength, especially in experienced weightlifters.

We’ll get into the details of exactly how to do it later in this article, but at its core, rest-pause training is very simple:

You take a set to muscle failure (or just short of it), rest for a short period, do another set to near-failure, followed by a short rest and another set, and so on.

That’s it.

Why does it work, you wonder? Why can it help you gain muscle and strength faster?

Well, to answer that, we have to start by talking about why muscles grow bigger and stronger…

The Simple Science of Muscle Growth

There are three primary “pathways” to stimulate muscle growth:

1. Progressive Tension Overload

Progressive tension overload refers to increasing tension levels in the muscle fibers.

The most effective ways to do this are increasing intensity (the amount of weight you’re lifting) and volume (the number of reps you’re doing) over time.

That is, the best ways to overload your muscles are adding weight to the bar and making them do more work.

You see, muscles adapt quickly to strength training, and to keep improving, they have to be consistently exposed to increased tension levels through the addition of weight and/or reps.

This is why, as a natural weightlifter, if you want to keep getting bigger, you’re going to have to keep getting stronger.

It’s also partly why most studies on hypertrophy (muscle growth) have found the best results when people use heavier weights, usually at least 60% of their 1-rep max.

2. Muscle Damage

When you lift weights, your muscle cells deform and stretch, which causes small tears that must be repaired.

Our bodies don’t just repair muscle fibers to their previous state, either–they make them stronger and more resilient, able to better deal with such stresses in the future.

This is why, over time, it takes more and more overload to damage your muscle cells, which is why you have to keep making your workouts more and more challenging.

3. Cellular Fatigue

There are two basic dimensions to the functional capabilities of muscle.

1. How fully and forcefully it can contract.

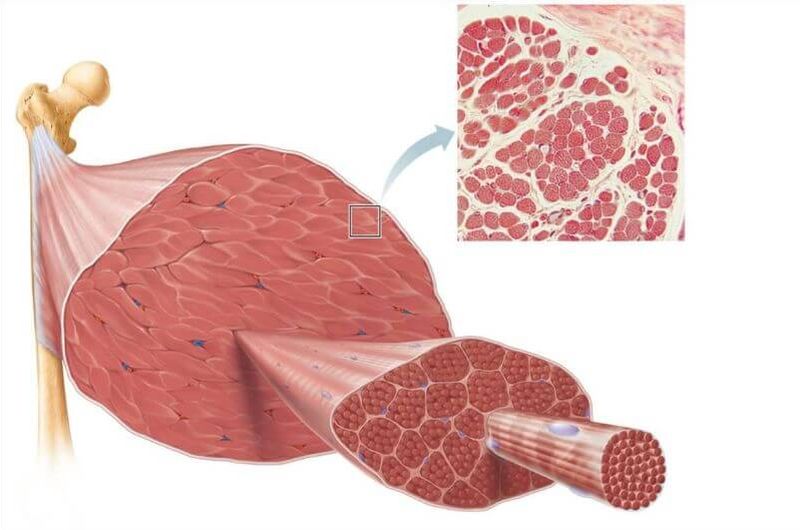

A muscle is comprised of many muscle fibers, which are comprised of many muscle cells.

Here’s how it looks:

Now, when a muscle is called upon to contract, the more individual muscle fibers that fire, and the harder they contract, the stronger that muscle will be.

One of the benefits of heavy weightlifting is it forces muscles to recruit as many muscle fibers and contract them as hard as possible.

This helps you more thoroughly overload your muscles and thereby increase muscle growth.

2. How many times it can contract before failing.

In many ways, muscle cells are like little engines.

They can only produce so much force–they only have so much natural “horsepower”–and can only do so much work until “redlining.”

In other words, it can only move so much weight and do so many repetitions of a movement before quitting.

Now, when a muscle cell “redlines,” it triggers a cascade of signals that lead to adaptations that increase muscle endurance and, to a degree, muscle size.

As you repeat this process over time, your muscle cells continue to adapt, and it takes more work for them to reach complete fatigue.

If you’re an experienced weightlifter, your muscles normally don’t reach this level of fatigue until close to the end of the workout (and it can take quite a bit of work to get there).

So, now that you understand the basic physiology of muscle growth, let’s see how rest-pause training fits in.

At bottom, rest-pause training helps you build muscle faster because it “pre-exhausts” your muscles, allowing you to push them to near-failure several times per set.

To stick with the engine metaphor, it allows you to “redline” your muscles under a moderate load more frequently, which, as you’ll see, can significantly impact muscle gain.

And, just as important, it allows you to do these things without much increasing the likelihood of overtraining.

Let’s take a minute to unpack all of this.

You’ve probably heard that the main triggers for muscle growth are only tapped in the last few reps of your sets–the grinders that light your muscle bellies on fire.

That’s not exactly true, but it’s not wholly off-base, either.

You see, one of the easiest ways to ensure you continue to overload, damage, and fatigue your muscles is to frequently push them to muscle failure, where you simply can’t get another rep, or close to it (one rep shy).

When you do this, you create much higher levels of muscle activation than with easier sets, which positively influences muscle building.

That’s why regularly pushing your muscles to the point failure, or just shy of it, is a very important aspect of gaining muscle and strength.

Now, with a normal weightlifting set, you only reach this point at the very end, after you’ve already done several reps.

Thus, if you wanted to increase the number of times your muscles taste failure in a workout, you’d need to do more sets and a lot more reps.

This is well and fine, but you can only do so many reps per major muscle group per week before your body falls behind in recovery and overtraining symptoms set in.

(And this is especially true if you’re emphasizing heavy, compound weightlifting in your workouts like a good little mensch.)

The beauty of rest-pause sets are they allow you to reach muscle failure several times in one set without greatly increasing workout volume.

Essentially, they’re a way to expose your muscles to powerful muscle-building stimuli more frequently without causing more muscle damage than your body can effectively repair.

Another big advantage of rest-pause sets is they’re a safe and time-effective way to increase workout volume (the number of reps you do in a workout).

You see, once you have a bit of weightlifting experience under your belt, increasing volume is a straightforward way to gain muscle mass.

If you make your muscles do more work over time, they’ll get bigger and stronger.

The problem with this is unless you’re on drugs or have unlimited free time, it’s difficult to keep adding volume to your workouts without spending your life in the gym or getting injured.

Rest-pause sets solve both of these problems.

They take far less time than traditional sets and because they involve lighter weights than your normal sets, the additional volume doesn’t put the same amounts of stress on your joints and nervous system.

For example, in one study, athletes who used rest-pause training were able to finish the same amount of volume 17 times faster. Muscle activation was also 13% higher on average using rest-pause training.

Another interesting fact was that the people doing rest-pause sets were able to lift just as efficiently after their workout as the people who had used longer rest periods.

In other words, rest-pause training helped them do more reps and achieve higher levels of muscle activation in less time, and without significantly higher levels of fatigue.

Rest-Pause Training 101

There are several popular styles of rest-pause training, but they all follow the same game plan:

- You start with an “activation set,” where you push your muscles to failure, or close to it.

- You rest for a short period, and do another mini-set.

- You repeat #2 until you can no longer match the reps from your first mini-set.

For example, let’s say you’re going to do some rest-pause sets with your biceps curls.

You start with a set of, let’s say, 12 reps, which is your activation set. You then rest 10 seconds, and do another set with the same weight, this time getting 5 reps.

You then repeat the process several times, resting 10 seconds and repping out until, after several sets, you can’t get 5–you can only get 3.

That’s the end of the rest-pause sets for that exercise.

Here’s what it might look like written down in your workout log:

30 x 12

Rest 10 seconds

30 x 5

Rest 10 seconds

30 x 5

Rest 10 seconds

30 x 5

Rest 10 seconds

30 x 3

Done

That’s the gist of it, but as I mentioned earlier, there are different ways to specifically program it.

Let’s look at two of the most popular methods.

The Doggcrapp Training Style of Rest-Pause Training

Doggcrapp Training, named after the online screen name of its creator, bodybuilder Dante Trudel, is a high-frequency, low-volume bodybuilding program that focuses on heavy weights, intense stretching, and rest-pause training.

In Doggcrapp Training, the rest-pause sets look like this:

- You start with a weight that you can do for 6 to 8 reps (around 75 to 80% of 1-rep max), and stop about one rep shy of failure.

- You then rest for 25 to 30 seconds and do another set of as many reps as possible, again stopping just short of failure.

- This is followed by a third and final set, which you push to absolute failure.

That’s it (as far as the rest-pause sets go, at least).

The Myo-Reps Style of Rest-Pause Training

Myo-Reps has been continually refined and updated since 2006 by bodybuilding coach Borge Fagerli.

It’s one of the most scientifically supported forms of rest-pause training, which has garnered it quite an “underground” following among competitive bodybuilders.

Here’s how it works:

1. You start light, picking a weight that you can do for 9 to 20 reps.

If you’re new to rest-pause training, you’ll want to go with about 30% of your 1-rep max. If you’re not, 40 to 50% should work well.

2. Take your first set to the point where you’re 1 to 2 reps shy of failure.

Fagerli also recommends that you reduce the range of motion slightly so that you aren’t locking out at the top or bottom of the lift.

The purpose of this is to keep the muscle under constant tension.

3. Rack the weight, and rest for 3 to 5 deep breaths.

One breath = in and out, so about 6 to 15 seconds.

4. Do another set of 3 to 5 reps, stopping a rep or two short of failure, rack the weight for 3 to 5 breaths, and repeat.

5. Stop when you hit 3 to 5 mini-sets or you lose one rep from the initial mini-set.

For example, all these would be correct:

Set 1: 20 reps

Mini-Sets: 4, 4, 4, 3

Set 1: 22 reps

Mini-Sets: 3, 3, 3, 3, 3

Set 1: 18 reps

Mini-Sets: 5, 4

And these would be incorrect:

Set 1: 20 reps

Mini-Sets: 4, 4, 3, 3

Set 1: 22 reps

Mini-Sets: 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3

Set 1: 18 reps

Mini-Sets:

5, 4, 3, 2

Getting Started with Rest-Pause Training

Rest-pause training is most effective when it’s worked into/around a well-designed workout program.

It’s not something you want to do exclusively or even too much, as it’s easy to burn yourself out if you get too zealous with it.

A good place to start is plugging rest-pause sets into your isolation exercises and accessory work, which should be at the end of your workouts, after your main lifts (which require a lot more energy).

For example, if you’re training back and start with a few sets of deadlifts and barbell rows and then move on to one-arm dumbbell rows and pullups, you would do your rest-pause sets with the dumbbell rows and/or pullups.

In time, you can increase the difficulty of your rest-pausing training by doing rest-pause sets with your bigger lifts, too.

When you do, though, you need to be very strict on form. Rest-pause training works because it fatigues the muscles far more than you’re used to, which is good for muscle growth, but also means that it puts you a higher risk of injury.

In terms of which method of rest-pause training to use, try both and see what you like most. I prefer Doggcrap’s method for compound lifts and Myo-Reps for isolation work.

The Bottom Line on Rest-Pause Training

If you’re a complete beginner (six months or less of consistent weightlifting), then this really isn’t for you…yet.

You’re better off sticking to a simpler, more traditional strength and bodybuilding programs like my Bigger Leaner Stronger program for men or Thinner Leaner Stronger program for women.

If, however, you’re an experienced weightlifter and you feel stuck or just want to see how your body responds to something new, rest-pause sets are worthwhile.

What are your thoughts on rest-pause training? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below.

Scientific References +

- Jùrgen Gieβsing, James Fisher, James Steele, Frank Rothe, Kristin Raubold, & Björn Eichmann. (n.d.). The effects of low-volume resistance training with and without advanced techniques in trained subjects - PubMed. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25303171/

- Marshall, P. W. M., Robbins, D. A., Wrightson, A. W., & Siegler, J. C. (2012). Acute neuromuscular and fatigue responses to the rest-pause method. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 15(2), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.08.003

- Burd, N. A., Holwerda, A. M., Selby, K. C., West, D. W. D., Staples, A. W., Cain, N. E., Cashaback, J. G. A., Potvin, J. R., Baker, S. K., & Phillips, S. M. (2010). Resistance exercise volume affects myofibrillar protein synthesis and anabolic signalling molecule phosphorylation in young men. Journal of Physiology, 588(16), 3119–3130. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192856

- Lamont, H. S., Cramer, J. T., Bemben, D. A., Shehab, R. L., Anderson, M. A., & Bemben, M. G. (2011). Effects of a 6-week periodized squat training with or without whole-body vibration upon short-term adaptations in squat strength and body composition. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(7), 1839–1848. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e7ffad

- Wernbom, M., Augustsson, J., & Thomeé, R. (2007). The influence of frequency, intensity, volume and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 37, Issue 3, pp. 225–264). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737030-00004

- Rasmussen, B. B., & Phillips, S. M. (2003). Contractile and nutritional regulation of human muscle growth. In Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews (Vol. 31, Issue 3, pp. 127–131). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003677-200307000-00005

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2013). Is there a minimum intensity threshold for resistance training-induced hypertrophic adaptations? In Sports Medicine (Vol. 43, Issue 12, pp. 1279–1288). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0088-z

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. In Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Vol. 24, Issue 10, pp. 2857–2872). J Strength Cond Res. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

- Marshall, P. W. M., Robbins, D. A., Wrightson, A. W., & Siegler, J. C. (2012). Acute neuromuscular and fatigue responses to the rest-pause method. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 15(2), 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.08.003