Key Takeaways

- Your main goal during your first few weeks back in the gym should be to train just enough to improve your muscle’s ability to resist soreness, and to improve your technique.

- To do this, you’ll want to train with relatively light weights, low volumes, a variety of rep ranges, and a higher than normal frequency.

- Keep reading to learn exactly what your workouts should look like and to get a free four-week training program to ease back into weightlifting!

So, here we are, hopefully closing in on the end of These Perilous Quarantimes.

Restaurants are opening, stonks are rising, and . . . at long last . . . gyms are unlocking their doors.

And that means a few things to us fitness folk:

- If you’ve been slogging through bodyweight workouts, and the idea of doing another set of pushups instead of bench press makes you want to huff paint and chew someone’s face off, your salvation is nigh.

- If you were lucky enough to snag some dumbbells or other exercise equipment before this thing went down (or were #dedicated enough to sell one of your kidneys in return for said exercise equipment), then you’ll be well-prepared to jump back into your old routine.

- And either way, you can look forward to a heaping bowl of good ‘ol fashioned muscle soreness, something you may not have experienced since your newbie gains days.

I’m talking stabbed in the thighs with a rusty butter knife . . . pecs bludgeoned by Sauron’s mace . . . spinal erectors so tender you could sell them at Outback Steakhouse . . . kind of sore.

And that’s not so good.

While muscle soreness can be a fun novelty, in a strange, masochistic sort of way, you actually want to avoid it as much as possible when getting back into a workout routine.

Why?

Because muscle soreness makes it difficult to train with heavy weights, or at all, which means it’ll take you even longer to regain any muscle and strength you lost during the lockdown.

So, how should you ease back into weightlifting when your gym reopens?

How should you adjust your workouts to minimize muscle soreness?

How long will it take until you can return to your old routine?

You’ll learn the answers to all of these questions in this article.

The short answer is that you want to train just enough to help your muscles become resistant to muscle soreness and improve your technique, but not so much that you cause significant muscle damage.

The longer answer? Keep reading to find out!

- Should You Go Back to the Gym When it Opens?

- How Fast Do You Lose Muscle and Strength After You Stop Lifting?

- How to Get Back into Weightlifting After a Break

- The Legion 4-Week Retraining Program

- The Bottom Line on How to Get Back Into Weightlifting

Table of Contents

+Should You Go Back to the Gym When it Opens?

This primarily depends on your health.

If you have any symptoms of COVID-19 or other respiratory diseases, or think you may have been recently exposed to someone who has the virus, stay home.

You may be familiar with a rule of thumb known as the “neck check,” which states that so long as your symptoms are above your neck, it’s safe to start working out again.

That is, as long as your symptoms are limited to your head—runny nose, sore throat, watery eyes, etc.—you can start training, but if your symptoms are below your neck—like a deep chest cough—you should rest until you’re better.

There’s very little scientific evidence supporting the “neck check,” but it’s been used by athletes for many years to good effect.

That said, you shouldn’t depend on the neck check right now.

Unless you’ve been tested and you’re sure you don’t have COVID-19, err on the side of safety, and to stay home at least until your symptoms are gone. Not only is this the right thing to do for the people around you and society at large, it also reduces the chances your gym will be shut down.

And what if you’ve tested positive for COVID-19 or think you might have COVID-19? When can you go back to training?

Two studies conducted by scientists at Royal Brompton Hospital and the Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute offer some helpful guidelines:

- If you’ve tested positive for COVID-19 or think you have COVID-19, don’t exercise for at least ten days while you see how your body responds to the illness (most people will have mild to no symptoms).

- Then, rest for at least another week or two, even if your symptoms are gone. This is partly to ensure you’re fully recovered, and partly to minimize the spread of the disease.

One of these papers recommends you see a doctor after recovering from COVID-19, while the other doesn’t list this as a recommendation.

It’s probably fair to say that if you’re particularly worried about how the virus may have affected your health, go see a doctor. If you’ve been symptom free for at least a week or two and don’t feel the need to visit a doctor, you probably don’t need to.

And what if you have COVID-19-like symptoms, but you test negative?

The authors of these two studies say you should still follow the same guidelines as if you do have COVID-19, which is probably sound advice. After all, even if you don’t have COVID-19, you could always have another respiratory illness like the flu, so it’s still a good idea to play it safe and stay away from the gym a little longer.

And finally, what if you don’t have COVID-19, and you’re worried about getting it from the gym?

This is obviously a personal choice that depends on your health and risk tolerance, but at this point, it’s fair to say that most healthy, relatively young to middle-aged people, don’t have much to worry about.

For example, a recent study conducted by scientists at Indiana State University found that the infection fatality rate—the total number of people who die after testing positive for COVID-19—was just 0.58%.

What’s more, the study also found that 45% of the people who were infected experienced no symptoms at all.

Although this study didn’t look at how the infection fatality rate changed based on age, the vast majority of these deaths were likely among the elderly (70+) and infirm, as has been the case more or less around the world.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), as of May 28, 2020, only 2,057 people in the United States under the age of 44 have died after having been diagnosed with COVID-19, accounting for just 2.5% of all COVID-related deaths in the U.S.

Even then, this doesn’t tell the whole story, as many of these people likely had pre-existing illnesses and health complications (obesity, diabetes, etc.), so it’s likely the actual mortality rate is much, much lower among healthy people.

While you obviously don’t want to get COVID-19 if you can avoid it, your risk of developing severe symptoms or dying if you’re a young, healthy, active person, is vanishingly low.

Still, it’s always possible you could pass the disease on to someone else who isn’t so robust, so it’s still worth taking measures to avoid catching the disease.

A few of these precautions include:

- Washing your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before and after going to the gym

- Trying to go to the gym during off-peak hours, such as the early morning, late morning, or late evening

- Maximizing your physical distance from other people in the gym (six feet is a good minimum, more is better)

Summary: If you’re healthy, symptom free, and haven’t knowingly been exposed to someone with COVID-19 in the past week or so, you can safely return to the gym once it opens.

How Fast Do You Lose Muscle and Strength After You Stop Lifting?

“I’ve definitely lost something,” a friend of mine told me as he kneaded his biceps, after returning from a week-long Christmas vacation. “I need to get back in the gym.”

Most of us can relate.

After not lifting weights for just a few days or weeks, many people say they look and feel smaller and weaker. You know, something like this . . .

And although a few weeks off won’t make you look this frail, your muscles will probably look a bit smaller and you’ll probably feel a bit weaker after just a week or two away from the gym.

But does that mean you’re really losing muscle?

And what if you’ve been doing home workouts? Surely that must have at least reduced the amount of muscle you’ve lost?

The truth is that your body holds on to muscle and strength remarkably well even if you stop lifting weights completely, and it’s unlikely you lost much of any muscle during the lockdown if you kept doing home workouts.

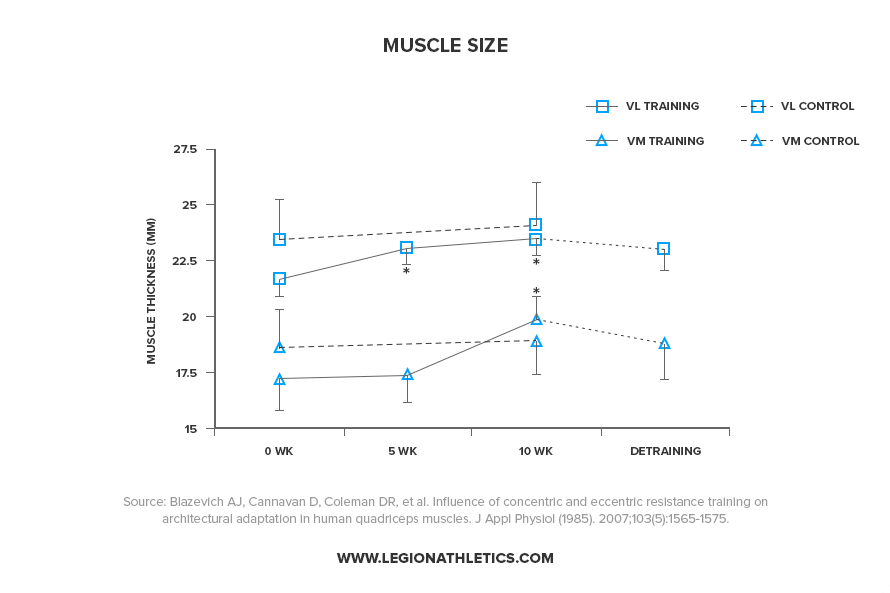

One of the best examples of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at Brunel University. In this case, the researchers had 33 untrained young men and women lift weights for 10 weeks, and then stop exercising for three months.

The researchers measured the participants’ leg muscle size and strength at various points throughout the study:

- Before beginning the weightlifting program

- After 5 weeks of weightlifting

- After 10 weeks of weightlifting

- After three months of no weightlifting or formal exercise

The result?

Although the participants did lose some of their strength and muscle gains after three months of not lifting weights, they didn’t lose as much as you might think.

Take a look at this graph:

As you can see, the participants gained muscle mass during the first 10 weeks of the study while they were lifting weights, and began losing muscle when they stopped lifting.

But here’s where things get interesting: after three months of no lifting whatsoever, their muscles were still about the same size as they were after five weeks of weightlifting.

That is, they only lost about five weeks’ worth of muscle gain after three freaking months of not lifting weights.

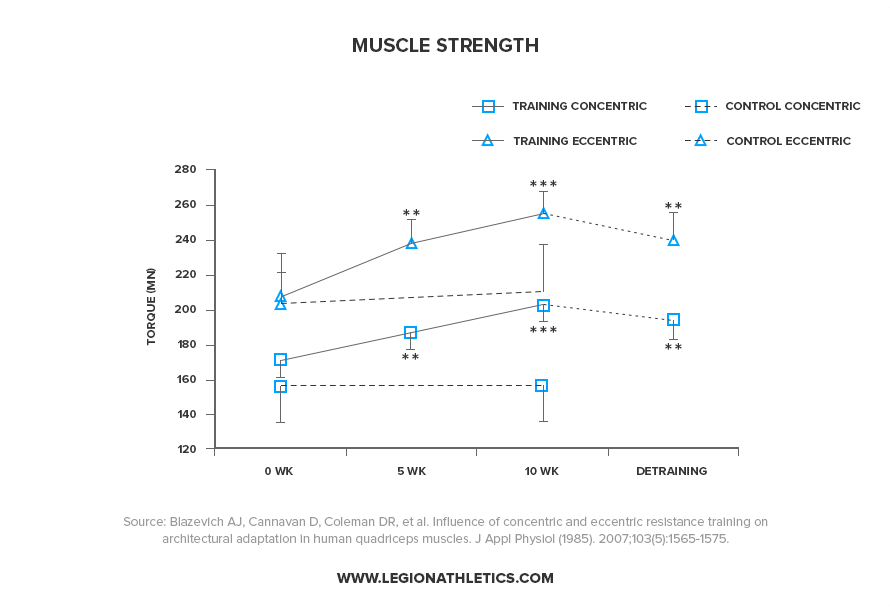

The researchers found the same result when they looked at strength:

Once again, the participants lost about five weeks’ worth of strength gains after three months of not lifting weights.

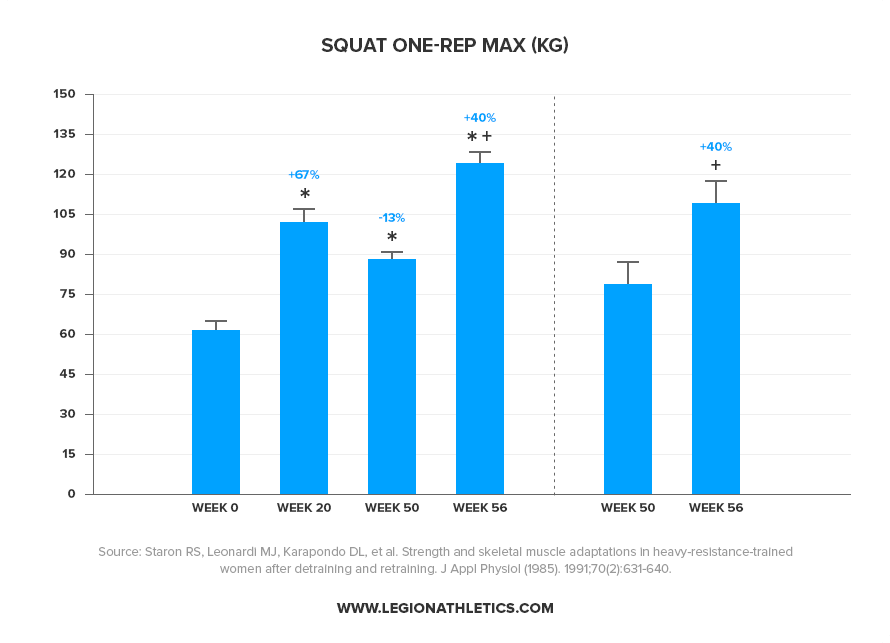

Scientists from Ohio University found similar results in another study on women. In this case, the researchers had six young, untrained women lift weights for 20 weeks, stop lifting weights for 30 weeks, and then lift weights again for 6 weeks.

This way, the researchers could not only measure how much muscle and strength the participants lost when they stopped weightlifting, but also how much they were able to gain back after they resumed training.

The researchers measured the participants’ muscle size and strength throughout the study, so they could see how the phases of training, detraining, and retraining affected their results.

Here’s what happened to their squat strength:

After 20 weeks of weightlifting, their strength shot up 67%.

After 30 weeks of no weightlifting, it went down 13% (relative to where they were after 20 weeks of weightlifting).

And after another 6 weeks of weightlifting, it shot up another 40% (again, relative to where they were after their break from weightlifting).

In other words, despite not lifting weights for nearly eight months, these ladies only lost a small fraction of their squat strength. What’s more, they not only regained what they lost after just a few weeks, but they set new PRs along the way.

The same thing was true when the researchers looked at their muscle fibers under a microscope.

Their muscle fibers grew significantly bigger after lifting weights for 20 weeks, shrunk a little after 30 weeks of not lifting weights, and grew bigger than ever after 6 more weeks of weightlifting.

The bottom line:

It takes a lot longer to lose muscle and strength than most people realize.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that all of the people in these studies were beginners, which means their bodies were hyperresponsive to the effects of resistance training. The closer you are to your genetic potential for strength and muscle mass, the more effort it takes to maintain and keep making progress.

Read: Everything You Should Know About Newbie Gains, According to Science

Thus, if these people were well-trained weightlifters, they probably would have noticed a larger decrease in muscle and strength after taking several months away from the gym.

How much?

Well, there aren’t any long-term detraining studies (the technical term for taking a break from training) on well-trained weightlifters, so we don’t know for sure. One study on 20 male weightlifters found they didn’t lose any muscle after a two-week break from weightlifting, but we don’t know what would have happened after four, eight, or more weeks without training.

Based on the research we do have, though, it seems unlikely they would have lost enough muscle to see a significant difference in their appearance.

There’s something else you should know about all of these studies: these people weren’t lifting weights or doing any kind of formal exercise for months at a time.

Research shows you can maintain strength and muscle with only a fraction of the effort it takes to gain them in the first place. If you were doing any kind of bodyweight, band, or dumbbell/kettlebell workouts over the past few months, you probably didn’t lose much of any strength or muscle to speak of.

Read: The Best Home Workout Routines for When You Can’t Go to the Gym

So, it’s impossible to predict exactly how much muscle you’ll lose when not lifting weights, and this can be greatly influenced by your activity levels, whether or not you do some kind of weightlifting or none at all, your diet, and other factors.

Assuming you do lose some muscle and strength during your break, though, how long will it take to regain them?

Once again, there aren’t any studies on well-trained athletes to help us answer this question, but Dr. Mike Zourdos, a professor of exercise science at Florida Atlantic University, powerlifter, writer, and coach, estimates that it takes about half as long to regain your lost strength and muscle as it did to lose it.

That is, if you take 4 to 6 months off, you’ll probably need to take 2 to 3 months to get back to where you were.

Based on my experience, that’s a reasonable guess.

So, circling back to the original question, how fast do you lose muscle and strength, and how quickly can you regain them?

If you completely stop weightlifting, you’ll probably lose very little muscle or strength even after a month or two.

If you train even a little bit, even if it’s suboptimal (bodyweight training, etc.), you probably won’t lose much of any muscle or strength for many months.

And even if you do lose muscle and strength after a hiatus from heavy weightlifting, you’ll gain back that muscle pretty fast—probably in a matter of weeks.

Okay okay, you might be thinking, that’s cool and all, but when I look in the mirror, I can see I’m smaller. What has your high-falutin science got to say about that?

Quite a bit!

You see, it’s entirely possible that you have lost muscle size since you stopped lifting weights, but it’s not because you lost actual muscle tissue.

Instead, what you’re probably seeing is a decrease in muscle glycogen levels. Glycogen is a form of carbohydrate that’s stored in muscle cells for energy, and each gram of glycogen is stored with three to four grams of water.

Thus, 100 grams of glycogen is stored with around 300 to 400 grams of water.

Working out greatly increases your muscles’ ability to store glycogen, and when you stop working out, your muscles’ glycogen levels drop precipitously (along with the extra water attached to that glycogen).

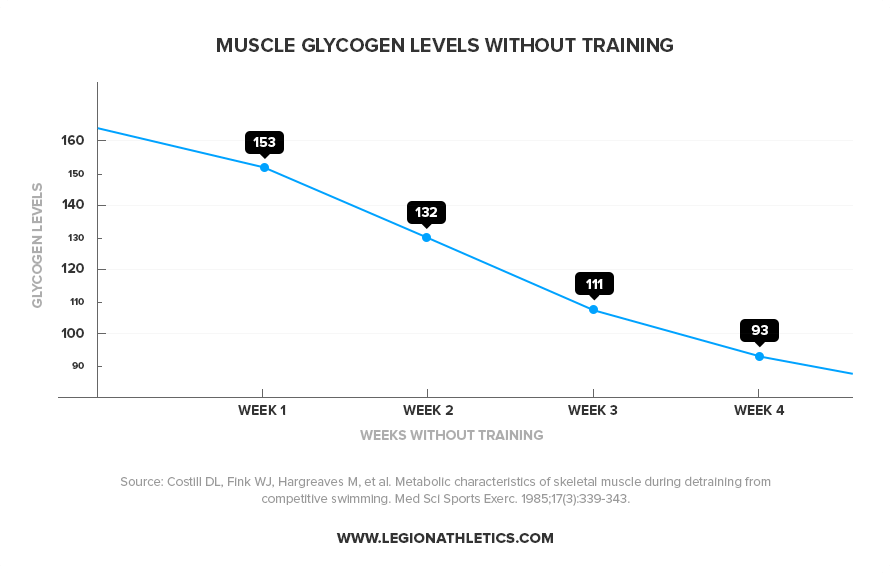

For example, take a look at this graph from a study conducted by scientists at Ball State University on well-trained swimmers:

After just one week of not training, the athlete’s muscle glycogen levels dropped 20%, and they were nearly 50% lower after a month of not working out.

Every little decrease in glycogen stores slightly decreases the size and appearance of your muscles, which is why detraining makes your muscles look and feel smaller.

In other words, it’s totally normal for your muscles to look a bit smaller after a break from weightlifting. Assuming you’ve only taken a short break from weightlifting, this is most likely due to a decrease in glycogen stores, not due to actual muscle loss.

What’s more, when you start training again, your glycogen stores will rise and your muscles will swell to their former, larger size.

Finally, there’s one more big caveat to all of this: your diet has a major impact on your ability to maintain muscle during a break from training.

If you’re severely restricting calories or not eating enough protein while taking a break from weightlifting, you’ll lose far more muscle than if you were to follow a moderate calorie deficit or eat enough to maintain your weight and sufficient protein.

Likewise, if you want to regain muscle and strength as fast as possible when you return to the gym, you’ll want to eat enough to maintain your weight or a slight surplus, and sufficient protein.

Read: This Is the Best Macronutrient Calculator on the Net (Updated 2020)

Alright, enough dwelling on the past.

No more talk of how much muscle or strength you may or may not have lost and what you could have done to prevent it.

Gyms are reopening, which means it’s time to look to the future!

Let’s talk about how you should train when you’re back in the gym.

Summary: You only start to lose muscle and strength after several weeks of not training, and you can probably avoid losing any muscle or strength by doing home workouts, eating at maintenance or in a slight calorie deficit, and eating sufficient protein. You’ll regain most of the muscle and strength you lost in a few weeks after you begin lifting again.

How to Get Back into Weightlifting After a Break

When returning to the gym, your first inclination will be to jump back into your old workout routine.

This is probably a bad idea.

First and foremost, your muscles have become much more sensitive to the effects of weightlifting, which comes with pros and cons.

On the one hand, you’ll quickly gain back any strength and muscle you may have lost. On the other hand, it also means your muscles will be far more susceptible to muscle damage, and you’ll get a lot more sore after your workouts.

This is true even if you’ve been doing home workouts, because heavy barbell training produces much more tension in your muscles and thus causes significantly more muscle damage and soreness.

Read: Do You Actually Want Sore Muscles? (Does It Mean Muscle Growth?)

What’s more, your technique on the compound lifts like the squat, bench press, deadlift, and overhead press, will be rusty, increasing the risk of injury and limiting how much you can lift.

And finally, you probably won’t progress any faster by diving back into your old workout routine than if you were to ease back into heavy barbell training for two reasons:

- As you learned a moment ago, your muscles will be primed to get bigger and stronger, and in the beginning, you won’t have to train that hard or that heavy to make rapid progress.

- Muscle soreness from your first few workouts will likely interfere with your ability to add weight and improve your technique, and it may even force you to skip a few workouts.

In the final analysis, then, the cons of jumping back into your old weightlifting routine far outweigh the pros.

So, what should you do instead?

During your first few weeks back in the gym, your primary goal should be to train in a way that prepares your muscles for heavy weightlifting and improves your technique.

That is, you’ll want to gradually reintroduce your muscles to strength training and work on improving your squat, bench press, deadlift, and military press form. After a few weeks of this kind of training, you can safely and productively transition back into your old workout routine.

Here’s how you’ll want to train during your first month back in the gym:

Use 50 to 80% of your one-rep max for your compound exercises.

Thanks to a phenomenon known as the repeated bout effect, your muscles become significantly more resistant to damage from strength training after just a few workouts.

This is why you got so incredibly sore after weightlifting when you were new to strength training, but stopped getting sore after the first few weeks.

Here’s something many people don’t know: you don’t have to train all that heavy or hard to reap the benefits of the repeated bout effect.

That is, training with relatively light weights will protect your muscles from damage caused by heavy weightlifting. For example, in one study, scientists from National Taiwan Normal University split 24 untrained young men into two groups:

Group one performed a workout using just 10% of their maximum voluntary strength (that is, about a 1 out of 10 in terms of intensity on a scale from 1 to 10). They trained almost every major muscle group in the body, including the biceps, triceps, chest, quads, hamstrings, calves, las, abs, and spinal erectors.

Then, two days later, everyone returned to the lab and performed another workout using 80% of their maximum strength, training all of the same muscles.

In this way, the first workout acted as a kind of introductory workout for the harder session two days later.

Before and after both workouts, the researchers measured the participants’ muscle damage and soreness in a variety of ways, including blood tests for markers of muscle damage, subjective ratings of muscle soreness, and how hard each person could contract their muscles.

Group two performed a workout using 80% of their maximum voluntary strength, but didn’t perform any kind of easier training before their workout. The researchers took all of the same measurements as they did for group one, and then compared them.

The result?

Group one experienced significantly less muscle soreness and a smaller decrease in strength than group two after their workout with heavier weights.

Here’s the coolest part:

The participants in group one didn’t experience a significant increase in muscle soreness or decrease in strength after their introductory workout with light weights.

By performing an easy workout with light weights, the participants in group one were able to protect their muscles from muscle damage when they used heavy weights just two days later. That is, their muscles “overreacted” to a relatively easy workout by becoming much more resistant to muscle damage and soreness caused by a difficult workout.

What does this mean for you?

You’ll want to use lighter weights for your first few weeks back in the gym. This will cause very little muscle damage or soreness, but will greatly reduce the amount of muscle damage and soreness you experience when you start using heavier weights again.

How light should your weights be?

Well, the people in this study were completely untrained, which means they were much more sensitive to muscle damage than people who have some weightlifting experience, like you probably do. Even if you’ve been taking a break for a few months, you’ll still be more resistant to muscle damage than someone who’s never lifted weights before.

This is especially true if you’ve been doing home workouts during the lockdown. Thus, you’ll probably want to use heavier weights than the people in this study to better prepare your muscles for the demands of heavy weightlifting.

Here’s how much weight I recommend you use in your workouts during your first week back in the gym:

- Use about 50% of your one-rep max (1RM) on your compound exercises.

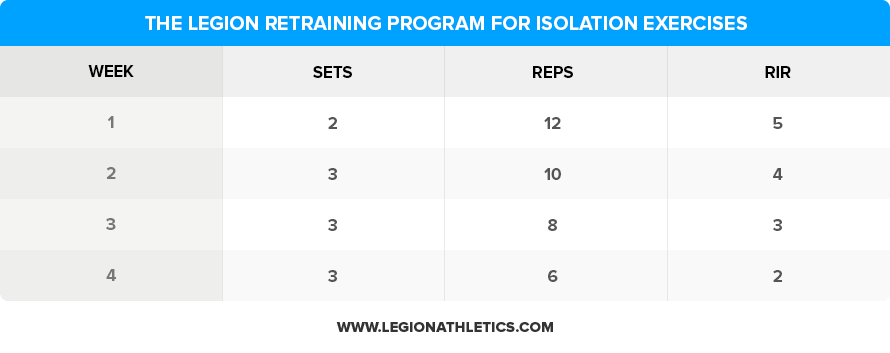

- Use 5 reps in reserve (RIR) on your isolation exercises.

In case you aren’t familiar with the concept, RIR indicates how many more reps you could do in a set if you absolutely had to.

If you’re like most experienced weightlifters, this is how you talk about your weightlifting sets. After a set of hard barbell curls, for instance, you might say, “Man, that was a grinder—I had maybe one rep left in the tank,” which would be an RIR of 1.

Thus, an RIR of 5 means you could do five more reps if you absolutely had to.

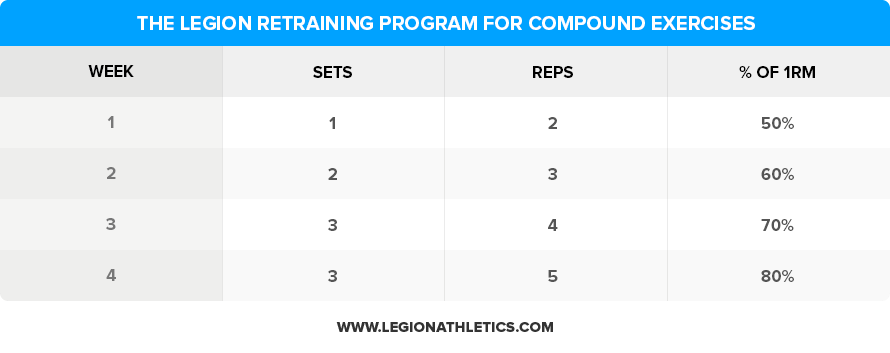

After your first week back in the gym, you’ll bump up the intensity of your compound exercises to 60% of your 1RM, and the intensity of your isolation exercises to 4 RIR. On week three, you’ll use 70% of 1RM for your compound exercises and a 3 RIR for your isolation exercises. And on week four, you’ll use 80% of your 1RM on compound exercises and 2 RIR on isolation exercises.

Do 1 to 3 sets per compound exercise and 2 to 3 sets per isolation exercise.

How many sets you do in each workout (your workout volume) also determines how much muscle damage and soreness your workouts cause.

And, like intensity, you don’t need to do much volume to help protect your muscles from damage and soreness.

Moreover, doing relatively short, low-volume workouts is also a great way to improve your weightlifting technique. When you’re only doing a handful of sets, you never get fatigued enough for your form to start falling apart, and thus the overall quality of your reps tends to be higher.

As your body grows accustomed to weightlifting again, you’ll also want to gradually increase your workout volume to make your workouts more challenging. (Gradually increasing your volume like this is also the best way to prevent overuse injuries).

Here’s the plan:

- During your first week back in the gym, do just one set per compound exercise and two sets per isolation exercise.

- During your second week in the gym, do two sets per compound exercise and three sets per isolation exercise.

- During your third and fourth weeks in the gym, do three sets for all of your compound and isolation exercises.

This ensures muscle damage, soreness, and fatigue never get out of hand, reduces your risk of injury, and helps you rapidly improve your weightlifting technique.

Do 2 to 5 reps per set on your compound exercises.

Just as doing too many sets in a single workout can cause excess muscle damage, soreness, and fatigue, doing too many reps in each set can produce a similar effect.

This is mainly true of compound exercises like the squat, bench press, deadlift, and overhead press, where high-rep sets tend to be disproportionately damaging and fatiguing.

Low-rep sets are also ideal for improving your technique, because they allow you to get in lots of quality repetitions with minimal fatigue.

All of this is why I recommend you only do sets of 2 to 5 reps on your compound exercises during your first month back in the gym.

And what about your isolation exercises?

You could use low or high reps for your isolation exercises, but I recommend you start by using higher reps and progress to using lower reps.

Why?

- Using a variety of rep ranges is likely better for muscle growth.

- Many isolation exercises (like dumbbell side raises and lat pulldowns) are better suited to higher reps than lower reps.

- It adds some enjoyable variety to your training.

- It exposes your muscles to multiple rep ranges, which ensures you’re well prepared for whatever program you decide to follow after your first month back in the gym.

Specifically, I recommend you begin your first week back in the gym by doing 12 reps per set for your isolation exercises, then 10 reps per set on week two, 8 reps per set on week three, and 6 reps per set on week four.

Squat and bench press twice per week and deadlift and military press once per week.

Your workout frequency refers to how many times per week you train a particular muscle group or exercise.

Normally, a good rule of thumb for maximizing muscle growth is to train each muscle group at least twice per week, and a good rule of thumb for maximizing strength gains is to train each compound exercise you want to improve at least once per week.

That said, one of the best ways to get better at any movement, whether it’s swinging a golf club, swimming laps, or squatting a heavy barbell, is to practice frequently.

And remember, one of your goals during your first month back in the gym is to improve your weightlifting technique as quickly as possible. Not only will this help you get back to lifting heavy weights, it will also reduce your risk of injury.

So, during your first few weeks back in the gym, I recommend you bench and squat twice per week and deadlift and military press once per week.

The reason I recommend you deadlift only once per week, is because it’s the least technically demanding of the three lifts and tends to cause more muscle damage, soreness, and fatigue, all of which you want to minimize.

The reason I recommend you military press once per week, is it doesn’t allow you to move as much weight as the bench press, and it’s generally not as important to most people.

Squatting and bench pressing, though, are more technically demanding, tend to be less tiring, and are responsible for the lion’s share of your whole-body muscle and strength gains.

Once your squat, bench press, deadlift, and military press technique is back up to snuff and you’re no longer getting sore after your workouts, you can switch back to your regular workout routine.

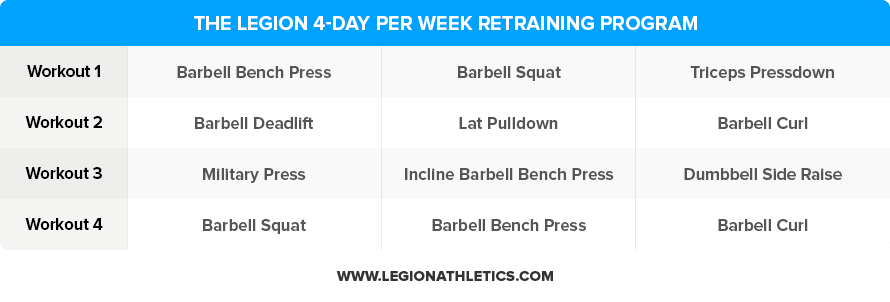

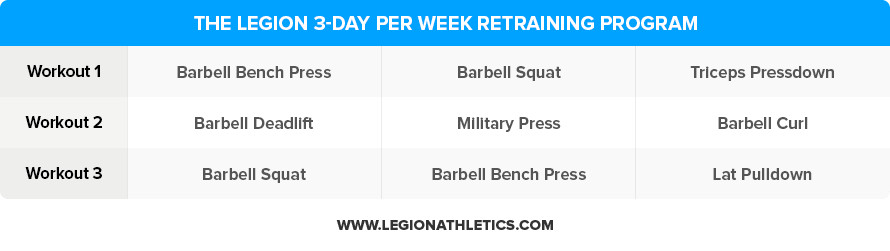

The Legion 4-Week Retraining Program

Let’s quickly recap the key tenets of this program:

- Use 50 to 80% of your one-rep max for your compound exercises.

- Do 1 to 3 sets per compound exercise and 2 to 3 sets per isolation exercise.

- Do 2 to 5 reps per set on your compound exercises.

- Squat and bench press twice per week and deadlift and military press once per week.

Here’s the general outline of what your sets, reps, and intensity should look like for your compound and isolation exercises:

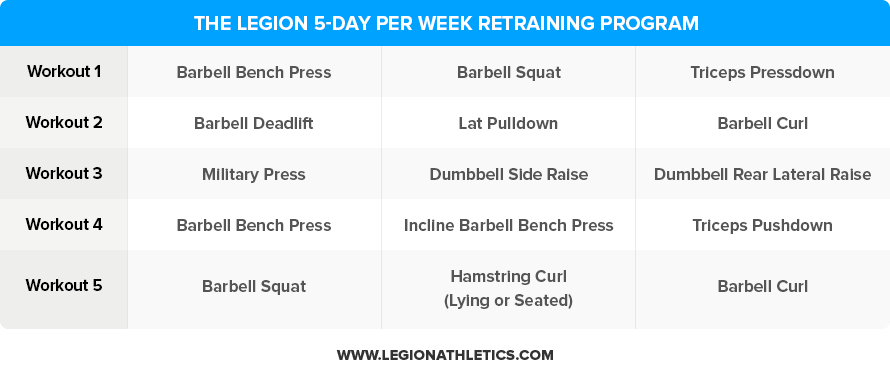

I’m also going to give you three different workout routines, depending on whether you want to train three, four, or five times per week.

Here they are:

And a few more notes on how to get the most out of these programs . . .

Warm up before each workout.

Before your first set of your first exercise of each workout, make sure you do a thorough warm-up.

A warm-up accomplishes several things:

- It helps you troubleshoot your form and “groove in” proper technique (which is particularly important when you’re relearning an exercise).

- It can significantly boost your performance, which can translate into more muscle and strength gain over time.

In weightlifting, a warm-up consists of doing one or two light sets of an exercise, followed by one or two heavier sets until you’re using a weight that’s about 70% as heavy as the heaviest weight you’ll use that day for that particular exercise.

Here’s how to warm up properly:

Do several warm-up sets with the first exercises for each of the muscle groups you’re training in that day’s workout.

For example, in Workout 1 in the 5-day workout program outlined in this article, your first exercise is the barbell bench press, which trains your chest, triceps, and shoulders.

Thus, warming up for the barbell bench press will also warm up all of the muscles trained by the triceps pressdown, but not the barbell squat.

So, in this case, you can do a few warm-up sets for your barbell bench press, then your hard sets, and then you’d warm up for the barbell squat and do your hard sets for that exercise. Then, you can do your triceps pressdowns without any additional warm-up sets (since the muscles trained in this exercise will still be warmed up after the bench press).

Here’s the protocol you’re going to follow for the workouts in this article:

- Estimate roughly what weight you’re going to use for your three sets of flat barbell bench press (this is your “hard set” weight).

- Do 10 reps with about 50 percent of your hard set weight, and rest for a minute.

- Do 10 reps with the same weight at a slightly faster pace, and rest for a minute.

- Do 4 reps with about 70 percent of your hard set weight, and rest for a minute.

Then, do all of the hard sets prescribed for that exercise.

Now, you may be wondering, do you really need to warm up for your workouts for the first two weeks of this program? After all, you’re only using 50 to 60% of your 1RM.

Well, no, you don’t, but it’s probably still a good idea.

I recommend you do a modified warm-up with only two sets. Do one set with just the bar, and then one set with about 70% of the weight I’ll be using that day.

For example, if I’m working up to 160 pounds for my bench press (about 50% of my 1RM), I might do one warm-up set with just the bar (45 pounds), and then one warm-up set with 115 pounds.

Once you enter Week 3 of this program, though, you’ll want to follow the normal warm-up protocol.

If you want to learn more about the importance of a proper warm-up and how to warm up for different workouts, check out this article:

Rest 3 to 4 minutes in between each set.

This will give your muscles enough time to fully recoup their strength so you can give maximum effort each set.

If you want to learn more about how long you should rest between sets, check out this article:

Read: How Long Should You Rest Between Sets to Gain Muscle and Strength?

Switch to a different strength training program after four weeks.

This retraining program is meant to do exactly that . . . help you retrain your muscles so you’re ready to follow a more challenging workout routine again.

Although you can stick with this routine, you’ll make faster progress by following one with more volume, intensity, and exercise variety.

If you’re looking for a workout routine that will help you build muscle, get stronger, and lose fat, check out these articles:

⇨ The 12 Best Science-Based Strength Training Programs for Gaining Muscle and Strength

⇨ The Definitive Guide on How to Build a Workout Routine

⇨ The Definitive Guide to the “Push Pull Legs” Routine

⇨ This Is The Last Upper Body Workout You’ll Ever Need

⇨ This Is the Last Lower Body Workout You’ll Ever Need

⇨ How to Get a Bigger and Stronger Chest in Just 30 Days

⇨ How to Get Bigger and Stronger Legs in Just 30 Days

⇨ How to Get Bigger and Stronger Biceps in Just 30 Days

⇨ How to Get Bigger and Stronger Shoulders in Just 30 Days

The Bottom Line on How to Get Back Into Weightlifting

Although you may feel significantly smaller and weaker after the lockdown, you probably didn’t lose much of any muscle or strength to speak of.

Research shows that even if you quit weightlifting completely, you still retain most of your strength and muscle mass several months later. What’s more, if you did home workouts during the quarantine, you probably didn’t lose any of your gains.

That said, even if you trained at home, your muscles are likely much more susceptible to damage and soreness caused by heavy weightlifting.

As a result, you want to gradually ease back into barbell training.

During your first few weeks back in the gym, your primary goal should be to train in a way that prepares your muscles for heavy weightlifting and polishes your technique.

To that end, here’s what you should do:

- Use 50 to 80% of your one-rep max for your compound exercises.

- Do 1 to 3 sets per compound exercise and 2 to 3 sets per isolation exercise.

- Do 2 to 5 reps per set on your compound exercises.

- Squat and bench press twice per week and deadlift and military press once per week.

Follow one of the programs in this article for just four weeks, and you should have no trouble transitioning back into your old workout routine (or a new, more challenging one!).

What do you think about getting back to training? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Pope, Z. K., Benik, F. M., Hester, G. M., Sellers, J., Nooner, J. L., Schnaiter, J. A., Bond-Williams, K. E., Carter, A. S., Ross, C. L., Just, B. L., Henselmans, M., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Longer interset rest periods enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy in resistance-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(7), 1805–1812. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001272

- Fradkin, A. J., Zazryn, T. R., & Smoliga, J. M. (2010). Effects of warming-up on physical performance: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(1), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c643a0

- Gabriel, D. A., Kamen, G., & Frost, G. (2006). Neural adaptations to resistive exercise: Mechanisms and recommendations for training practices. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 36, Issue 2, pp. 133–149). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636020-00004

- Nosaka, K., Sakamoto, K., Newton, M., & Sacco, P. (2001). How long does the protective effect on eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage last? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(9), 1490–1495. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200109000-00011

- Huang, M. J., Nosaka, K., Wang, H. S., Tseng, K. W., Chen, H. L., Chou, T. Y., & Chen, T. C. (2019). Damage protective effects conferred by low-intensity eccentric contractions on arm, leg and trunk muscles. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(5), 1055–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04095-9

- Connolly, D. A. J., Reed, B. V., & McHugh, M. P. (2002). The repeated bout effect: Does evidence for a crossover effect exist? Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 1(3), 80–86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3967433/

- D L Costill, W J Fink, M Hargreaves, D S King, R Thomas, R. F. (n.d.). Metabolic Characteristics of Skeletal Muscle During Detraining From Competitive Swimming - PubMed. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3160908/

- Bob Murray1 and Christine Rosenbloom2. (n.d.). Fundamentals of glycogen metabolism for coaches and athletes. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6019055/

- S N Kreitzman 1, A Y Coxon, K. F. S. (n.d.). Glycogen Storage: Illusions of Easy Weight Loss, Excessive Weight Regain, and Distortions in Estimates of Body Composition - PubMed. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1615908/

- Bickel, C. S., Cross, J. M., & Bamman, M. M. (2011). Exercise dosing to retain resistance training adaptations in young and older adults. In Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (Vol. 43, Issue 7, pp. 1177–1187). Med Sci Sports Exerc. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318207c15d

- Hwang, P. S., Andre, T. L., McKinley-Barnard, S. K., Morales Marroquín, F. E., Gann, J. J., Song, J. J., & Willoughby, D. S. (2017). Resistance Training–Induced Elevations in Muscular Strength in Trained Men Are Maintained After 2 Weeks of Detraining and Not Differentially Affected by Whey Protein Supplementation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(4), 869–881. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001807

- Staron, R. S., Leonardi, M. J., Karapondo, L., Malicky, E. S., Falkel, J. E., Hagerman, F. C., & Hikida, R. S. (1991). Strength and skeletal muscle adaptations in heavy-resistance-trained women after detraining and retraining. Journal of Applied Physiology, 70(2), 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1991.70.2.631

- Blazevich, A. J., Cannavan, D., Coleman, D. R., & Horne, S. (2007). Influence of concentric and eccentric resistance training on architectural adaptation in human quadriceps muscles. Journal of Applied Physiology, 103(5), 1565–1575. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00578.2007

- Phelan, D., Kim, J. H., & Chung, E. H. (2020). A Game Plan for the Resumption of Sport and Exercise After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection. JAMA Cardiology. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2136