Box squats are an effective and knee-friendly alternative to traditional squats.

They’re beneficial because they “groove in” proper squat technique, develop explosive strength, and help you overcome strength plateaus.

In this expert guide, you’ll learn what box squats are, how to do a box squat with proper form, the benefits of box squats, which muscles they work, common mistakes to avoid, the best alternatives, and more.

Table of Contents

+

What Are Box Squats?

The box squat is a variation of the regular squat, which involves squatting down until you’re sitting on a box positioned behind you, and then standing back up.

It has two main uses:

- Novice weightlifters: For beginners, box squats are great for learning proper squat form. The box guides them to squat to the right depth and helps with balance.

- Experienced weightlifters: Advanced weightlifters incorporate box squats to refine their technique. The pause at the bottom of each rep also helps build the power needed to push through the hardest part of the squat—the point at which you begin to stand up from the bottom position, known as the “hole.”

How to Do a Box Squat with Proper From

Follow these steps to learn how to do a box squat with proper form:

1. Set up

Position a barbell in a squat rack at mid-chest height and place a sturdy knee-high box or bench 1-to-2 feet behind the rack.

Step under the bar, pinch your shoulder blades together, and rest the bar directly above the bony ridges on the bottom of your shoulder blades.

Lift the bar out of the rack, take a step or two backward, position your heels 1-to-3 inches from the box, and place your feet slightly wider than shoulder-width apart with your toes pointed slightly outward.

2. Descend

Take a deep breath into your stomach, push your chest out, brace your core, and sit down by bending at the knees and hips at the same time. Continue sitting down until your butt is on the box.

3. Squat

Drive through your feet to stand up and return to the starting position. This mirrors what you did during the eccentric phase (the descent).

Here’s how it should look when you put it all together:

The Benefits of Box Squats

Here are the three main benefits of box squats:

1. They’re gentler on your knees.

Thanks to the mechanics of the box squat, your shins remain more upright, and your knees bend less than with other types of squat, which reduces the stress on your knees.

Despite this, studies show that box squats are just as effective as regular, free squats for training your legs.

2. They help you refine squat technique.

Box squats help you refine your technique in three ways:

- They ensure your squat depth is correct on each rep, improving your technique’s consistency.

- They teach you to maintain an upright upper body, which helps you learn to balance correctly while squatting.

- They prevent the over-reliance on your “stretch reflex.” In other words, when you separate the lowering and lifting phases of the exercise by sitting on a box, you reduce your ability to use momentum, which helps you develop the control and coordination to squat properly.

3. They help you overcome plateaus.

Box squats are a powerful tool for overcoming strength plateaus because they allow you to strengthen the point of the exercise where you’re weakest—getting “out of the hole.” By coming to a dead stop at the bottom of each rep, they help you develop explosive strength, which is crucial for improving your overall squat performance.

Box squats also force you to use proper, efficient technique, which helps you progress through periods of stagnation.

Moreover, box squats boost your confidence when lifting heavy weights. Since you need to control the weight for longer, it helps you overcome the fear of squatting with heavy loads.

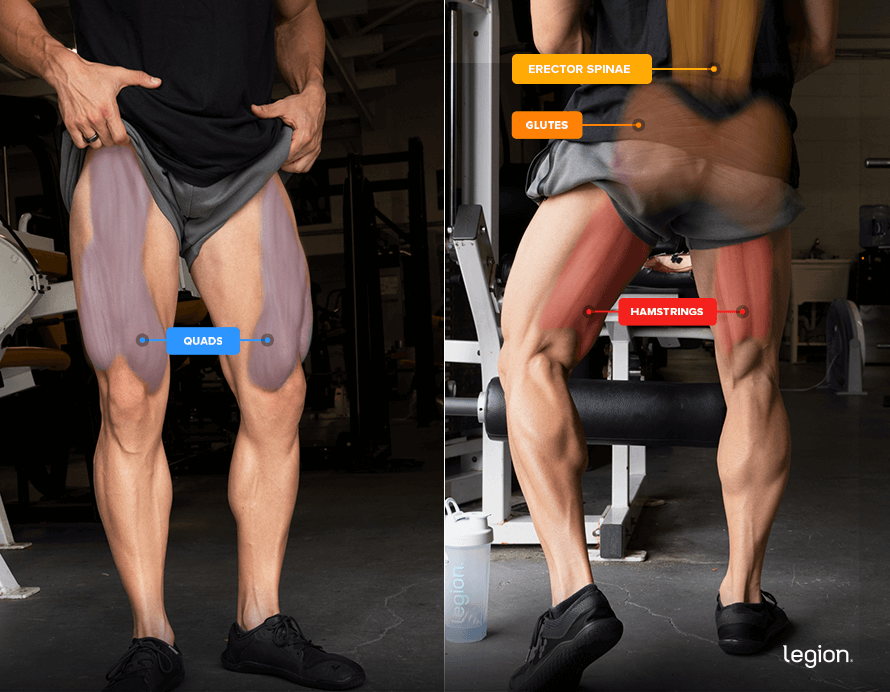

Muscles Worked by Box Squats

Box squats primarily train the quads and the posterior chain (the muscles on the back of your body), especially the lower back, hamstrings, and glutes.

They also work the abs and calves to a lesser degree.

Here’s how the main muscles worked by box squats look on your body:

Common Box Squat Mistakes

1. “Bouncing” off the box.

The problem: Some weightlifters mistakenly think that by rapidly descending in the box squat, you can “bounce” or “rebound” off the box to make lifting the weight easier. However, doing so reduces the exercise’s effectiveness, makes maintaining proper form more challenging, and increases your risk of injury.

The fix: To prevent bouncing, control your descent and pause when you sit on the box, stopping all momentum. Then, ensure you’re balanced and stable before standing up.

2. Using a box that’s too high or too low.

The problem: Using an inappropriately tall box can greatly reduce the exercise’s effectiveness and, in some scenarios, may increase your risk of injury.

The fix: Use a box that’s the right height for your physical abilities and fitness goals. For example, if you have knee issues, experiment with boxes taller than knee height to find one that allows you to train your legs without discomfort.

Conversely, choose a box below knee height to increase your squat strength through the lowest point of each rep. This will allow you to train through the most challenging range of motion, improving your squat performance.

3. Pausing for too long.

The problem: While a brief pause is beneficial for developing explosive strength and learning control, an extended pause can disrupt the exercise’s flow and reduce its effectiveness. It can also lead to unnecessary strain on the lower back.

The fix: Aim for a brief pause of about a second. This is enough to eliminate momentum, but not so long that you risk form breakdown or injury.

The Best Box Squat Variations and Alternatives

1. Low Box Squat

The low box squat involves sitting on a box lower than knee height. This increases the exercise’s range of motion, engaging the glutes and hamstrings to a greater degree.

The increased challenge and extended range of motion make the low box squat an ideal choice for those looking to get stronger out of the hole.

2. High Box Squat

In the high box squat, you squat onto a box higher than knee height, shortening the exercise’s range of motion and further reducing the stress on the knees.

The high box squat is beneficial for those who need a less challenging squat variation or have mobility or injury considerations.

3. Dumbbell Box Squat

The dumbbell box squat is a viable variation if you only have access to dumbbells. That said, you can lift more weight on the barbell box squat than the dumbbell box squat, making the barbell version better for gaining muscle and strength.

4. Bodyweight Box Squat

The bodyweight box squat is an ideal starting point for beginners because it allows you to practice squatting form without added resistance.

5. Bulgarian Split Squat

The Bulgarian split squat is a highly effective squat variation that’s kinder to the knees than regular squats, making it an excellent choice for those with knee issues.

6. Step-Up

Similarly to the box squat, the dumbbell step-up is an outstanding exercise for the entire lower body.

Moreover, the dumbbell step-up doesn’t require you to lift heavy weights to reap the benefits of the exercise, which means it’s kinder to your bones and joints than other squat variations.

7. Goblet Box Squat

The box goblet squat is an effective exercise for training your entire lower body, particularly your quads. Because you hold the weight in your hands rather than across your shoulders, it’s also easier on your back and knees than other squat variations.

FAQ #1: Why do powerlifters do box squats?

Powerlifters do box squats because they help build explosive strength, especially from the bottom of the squat. They also help improve squatting technique and can target specific weak points in your squat.

FAQ #2: Do you sit during a box squat?

Yes, you briefly sit on the box in the box squat. You lower yourself until your butt touches the box, pause for a beat to stop all momentum, and then stand back up.

You should keep the pause short, though—anything more than a second or so is too long and may increase the odds your form will break down. The goal of the pause is to eliminate momentum, not to take a rest.

FAQ #3: Is a box squat harder than a regular squat?

Squatting onto a box can be harder than a regular squat because starting the ascent from a dead stop requires more control and strength. It also removes the natural “bounce” that helps in regular squats, making your muscles work harder.

That said, you can typically squat more than you can box squat, which minimizes the difference.

Scientific References +

- Swinton, Paul A., et al. “A Biomechanical Comparison of the Traditional Squat, Powerlifting Squat, and Box Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 7, July 2012, pp. 1805–1816, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3182577067.

- Fry, Andrew C., et al. “Effect of Knee Position on Hip and Knee Torques during the Barbell Squat.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, vol. 17, no. 4, 1 Nov. 2003, pp. 629–633, journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/2003/11000/Effect_of_Knee_Position_on_Hip_and_Knee_Torques.1.aspx.

- McBride, Jeffrey M, et al. “Comparison of Kinetic Variables and Muscle Activity during a Squat vs. a Box Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 24, no. 12, Dec. 2010, pp. 3195–3199, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181f6399a. Accessed 13 Mar. 2020.

- Caterisano, Anthony, et al. “The Effect of Back Squat Depth on the EMG Activity of 4 Superficial Hip and Thigh Muscles.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 16, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2002, pp. 428–432, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12173958/.

- Kubo, Keitaro, et al. “Effects of Squat Training with Different Depths on Lower Limb Muscle Volumes.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 119, no. 9, 22 June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04181-y.

- Jones, Margaret T, et al. “Effects of Unilateral and Bilateral Lower-Body Heavy Resistance Exercise on Muscle Activity and Testosterone Responses.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 4, Apr. 2012, pp. 1094–1100, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e318248ab3b.

- DeFOREST, Bradley A., et al. “Muscle Activity in Single- vs. Double-Leg Squats.” International Journal of Exercise Science, vol. 7, no. 4, 2014, pp. 302–310, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27182408/.

- MACKEY, ETHAN R., and BRYAN L. RIEMANN. “Biomechanical Differences between the Bulgarian Split-Squat and Back Squat.” International Journal of Exercise Science, vol. 14, no. 1, 1 Apr. 2021, pp. 533–543, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8136570/.

- Simenz, Christopher J., et al. “Electromyographical Analysis of Lower Extremity Muscle Activation during Variations of the Loaded Step-up Exercise.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 12, Dec. 2012, pp. 3398–3405, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3182472fad.

- Selseth, Angie, et al. “Quadriceps Concentric EMG Activity Is Greater than Eccentric EMG Activity during the Lateral Step-up Exercise.” Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, vol. 9, no. 2, May 2000, pp. 124–134, https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.9.2.124. Accessed 9 May 2021.

- Krause Neto, Walter , et al. Gluteus Maximus Activation during Common Strength and Hypertrophy Exercises: A Systematic Review. Mar. 2020.

- Collins, Kyle S., et al. “Differences in Muscle Activity and Kinetics between the Goblet Squat and Landmine Squat in Men and Women.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. Publish Ahead of Print, 2 Aug. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000004094.