If you lift weights, you’ve probably gotten used to stiff, sore muscles.

Strangely, though, this stiffness and soreness often appears several hours or even days after your workouts.

This is known as delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS).

Just about everyone who works out with intensity experiences it, and some people even like it.

Others think it means their muscles are growing, others dislike it and try to avoid it, and others just suck it up and more or less ignore it.

So, is DOMS beneficial, harmful, or benign?

In other words, should you try to promote it, avoid it, or ignore it?

Well, the short answer is that it generally hurts your progress more than it helps, it doesn’t help you build muscle, and you shouldn’t change your training to promote DOMS.

That said, you probably will experience DOMS at one time or another if you’re following an effective workout plan, so you shouldn’t shy away from it either.

Ready for the longer answer?

Let’s start by defining delayed-onset muscle soreness.

- What Is Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)?

- What Causes DOMS?

- How Can You Prevent and Reduce DOMS?

- Can You Work Out When You Have DOMS?

- The Bottom Line on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness

Table of Contents

+What Is Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)?

Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is a dull aching pain that develops several hours after exercise, and typically peaks around 24 to 72 hours after a workout and disappears after four to seven days.

Typically, DOMS only hurts when you’re moving, such as when you’re standing, walking, stretching, or working out.

DOMS isn’t fundamentally different from regular muscle soreness. The only differences are that it develops hours or days after the workout instead of during or immediately after and it tends to be more painful.

At its worst, DOMS can make it difficult to use the affected muscles at all.

For example, it’s not uncommon for weightlifters, runners, or soccer players to have trouble walking for several days after a DOMS-inducing workout.

Most of the time, though, it’s a minor annoyance that shouldn’t significantly interfere with your workouts.

DOMS is often confused with muscle fatigue, but they aren’t the same thing.

Although both of these phenomena can be uncomfortable, muscle fatigue is caused by different factors.

As you’ll learn in a moment, DOMS is caused by muscle damage, and muscle fatigue is caused by either a buildup of metabolic “waste products” from muscle contraction, or a decrease in the ability of a nerve fiber to force a muscle to contract.

Most of the time, muscle fatigue manifests itself as exhaustion—the feeling you get after a long run. You aren’t exactly sore or in pain, but it feels like your batteries have been drained.

We don’t need to get into the nitty gritty of how fatigue occurs (which is still being furiously debated), but the bottom line is that it’s caused by different factors than delayed onset muscle soreness.

Summary: Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is a is a dull aching pain that develops several hours after exercise, and typically peaks around 24 to 72 hours after a workout and disappears after four to seven days.

What Causes DOMS?

DOMS has perplexed people for over a century, after first being described in 1902 by an MIT professor named Theodore Hough, who deduced that it was “ . . . fundamentally the result of ruptures within the muscle.”

Over 100 years later, his hypothesis still holds water.

Researchers aren’t exactly sure what causes DOMS, but the most promising theory is still the one put forth by Hough.

Delayed-onset muscle soreness is most likely due to small tears—called microtrauma—inside muscle cells. In other words, DOMS is caused by muscle damage.

To understand delayed onset muscle soreness on a deeper level (har har), you first have to understand how muscles contract.

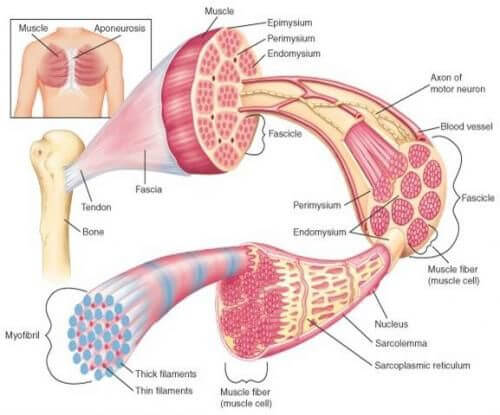

You can think of muscles like a living rope. Like rope, they’re made of extremely small fibers that are bound together in larger and larger bundles.

The largest bundle is the muscle, which typically attaches two bones in the body and pulls them together.

The next smallest bundle is the fascicle, which is a bundle of muscle fibers, aka muscle cells or myocytes.

The next smallest bundle is the myofibril, which makes up muscle cells.

And finally, myofibrils are made of the two smallest fibers in a muscle: actin and myosin.

These last two fibers are what drive muscle contraction throughout the body.

Here’s what the whole system looks like:

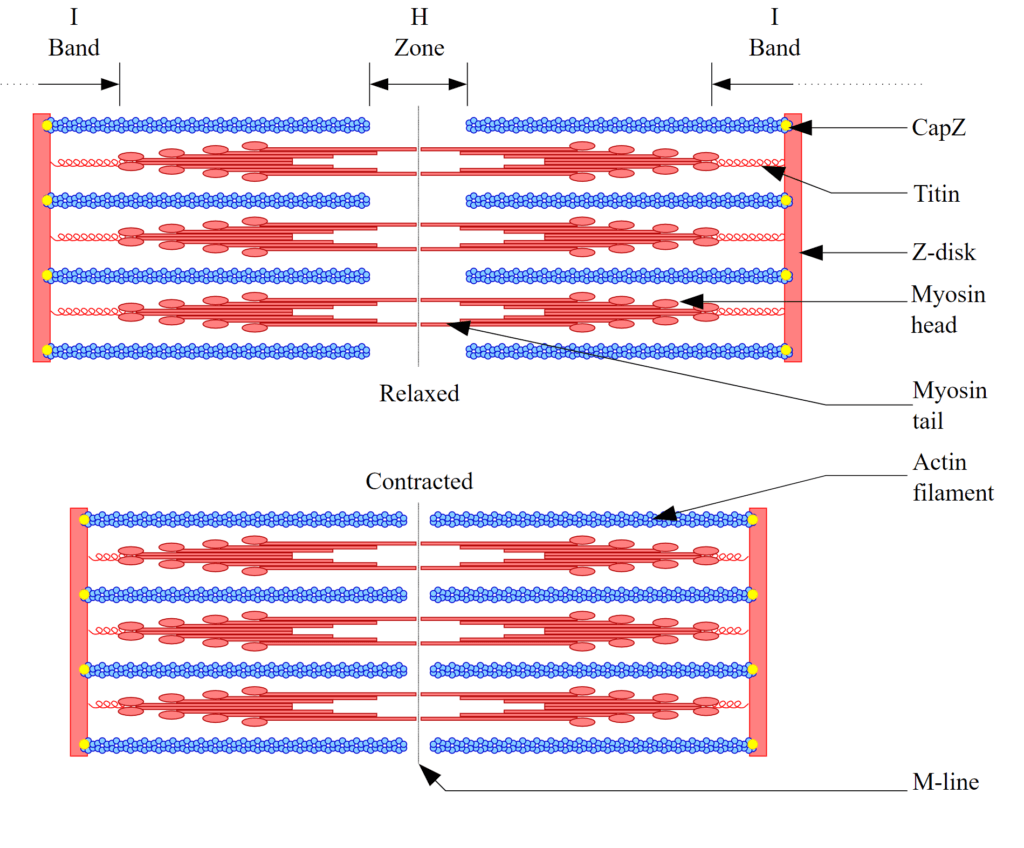

Actin and myosin fibers run parallel to one another throughout a myofibril, like this:

In this case, the blue fibers are actin and the red fibers are myosin.

When the brain tells a muscle fiber to contract, the myosin fibers tug on the actin fibers, causing them to “slide” up the actin fibers.

Here’s an excellent demonstration of what this looks like:

When the brain signals the muscle to relax, the myosin fibers “let go” of the actin fibers, allowing the myosin fibers to slide by the actin fibers, which causes muscle relaxation.

Muscle damage occurs when the myosin and actin fibers are pulled apart when they’re trying to hold onto one another. In some cases, researchers think the actin filaments may get uprooted from where they’re normally anchored inside the muscle, like a tendon snapping off of a bone.

Research also shows that a certain kind of exercise known as eccentric exercise causes the most muscle damage. Eccentric exercise is any kind of exercise that stretches a muscle while it’s contracting.

Take the biceps curl, for example.

When you raise the weight upward, your biceps muscle is undergoing concentric contraction, which doesn’t cause much of any muscle damage.

When you lower the weight toward the ground, though, the biceps muscle is undergoing eccentric contraction, because it’s still contracting as the weight pulls on the muscle.

This causes much more muscle damage than a concentric contraction, which is why eccentric training causes much more DOMS than concentric training.

The same thing occurs when you run downhill. Your hamstrings and quadriceps are contracting while being stretched, which causes a massive amount of muscle damage. Downhill running is so effective in this regard that it’s often used to cause muscle damage in studies.

Luckily, this damage isn’t permanent. The body has complex, robust, and efficient systems for quickly repairing damaged muscle fibers, which is why DOMS goes away after about a week at most.

This theory doesn’t explain everything, though.

For one thing, why wouldn’t the soreness kick in right after the damage occurred?

Scientists aren’t sure, but one popular explanation is that this damage impairs the muscle cells’ ability to process nutrients like calcium, which causes a buildup of other compounds like histamines, prostaglandins, and potassium in the muscle.

This triggers an inflammatory reaction, which causes delayed onset muscle soreness.

This process may take several hours, which is why delayed onset muscle soreness typically becomes apparent 12 to 24 hours after the workout.

That said, this is just a hypothesis, and researchers still aren’t entirely sure what the root cause of delayed-onset muscle soreness is.

Scientists do know what doesn’t cause DOMS, though.

Some people say that delayed-onset muscle soreness is caused by a buildup of lactic acid in the body, but this has been repeatedly disproven since the 1980s.

There are a few reasons this theory doesn’t hold up to scientific scrutiny:

- You can produce large amounts of lactic acid during a workout and then experience no DOMS.

- Lactic acid is almost entirely cleared from the muscle an hour after the workout, so it makes no sense that soreness would be highest almost a day later.

- Lactic acid is an important source of fuel for muscles during intense exercise, and new research shows it probably doesn’t even contribute to fatigue, much less soreness.

Summary: DOMS is caused by damage to muscle cells during a workout, and workouts that cause more muscle damage also typically cause more DOMS.

How Can You Prevent and Reduce DOMS?

The only surefire way to avoid DOMS is to never lift weights, and that’s obviously a non-starter for us fitness folk.

Ironically, the next best solution is to lift weights consistently.

Remember that the primary driver of DOMS is muscle damage. When you’re new to lifting weights or you’ve taken a long break (more than two weeks), your body becomes more susceptible to muscle damage from lifting weights.

This is why DOMS and muscle soreness in general tends to be worst when you start lifting weights for the first time or after a long break, and why it gets less and less severe the longer you lift weights.

In fact, the people who tend to endure the least DOMS are generally the most muscular, strongest, most experienced lifters.

So, if you want to minimize your chances of getting DOMS in the first place, lift weights consistently.

Even if you lift weights consistently, you can still get DOMS if you make a significant change to your workout program (switching from low reps to high reps, for example), but this DOMS is typically never as bad as it is when you first start lifting weights.

Assuming you’re already dealing with DOMS, what’s the best delayed-onset muscle soreness treatment?

Well, there are a handful of strategies that might help take the edge off, but the two most effective are:

Time and active rest.

First of all, there’s not much you can do to get rid of DOMS once it’s already sunk its hooks into you, so you just have to deal with it for a few days before your muscles recover. The good news is that this only takes a few days, and you’ll typically feel a lot better after three days.

Second, there’s some evidence that active rest, also known as active recovery, may help make DOMS disappear faster than complete rest.

That is, DOMS may go away faster if you do some light exercise instead of sitting on your butt on the couch.

If you want to try this technique, do some easy exercise like walking, swimming, cycling, rowing, or any other kind of low-impact activity when you aren’t lifting weights. You could also do higher reps and lighter weight, but cardio typically works better than weightlifting for active recovery.

Summary: The best way to avoid DOMS is to lift weights consistently, and the best way to reduce DOMS is to rest and do some light activity like walking, swimming, or cycling.

Can You Work Out When You Have DOMS?

Even though your muscle fibers are likely damaged if you’re sore, you can still have productive workouts when dealing with DOMS.

Whether or not you workout when you have DOMS depends on how bad the soreness is.

On the one hand, if you have trouble walking up stairs or getting out of bed in the morning, chances are good that you aren’t going to have very productive workouts.

What’s more, research shows that moderate to extreme muscle soreness can reduce the ability of your muscles to contract forcefully, which of course decreases your performance in the gym.

On the other hand, you might be surprised how little mild soreness interferes with your workouts.

There have been many times when I thought I was too sore to train, only to have a great workout.

In many cases, I still felt sore during my warmups, but once I started using heavier weights the soreness went away. I don’t know why this is, but I’ve found that you quickly forget about muscle soreness when you’re throwing around heavy weights.

So, if you’re a kinda sore and unsure if you can workout, go to the gym, warm up, and do at least one set. If it’s very uncomfortable, your RPE is way higher than it should be, and you have trouble maintaining good form, call it a day and wait until the soreness subsides before training that muscle group again.

If you feel good, your RPE isn’t too high, and you can maintain good form during your first heavy set, continue as you normally would.

Summary: You can still have a productive workout even if you’re sore, so in most cases you should be able to keep training even if you’re dealing with DOMS.

The Bottom Line on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness

Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is a dull aching pain that develops several hours after exercise, and if you lift weights, you’ll experience it at one time or another.

It’s typically most severe when you first start lifting weights, start lifting weights after a long break, or after you make a significant change to your workout routine.

Scientists have been studying DOMS for over a century, and while they still aren’t entirely sure what causes it, most evidence shows that muscle damage is the culprit.

Eccentric exercise, which involves lowering a weight or stretching a muscle while it’s contracting (like downhill running) tends to cause the most muscle damage and thus the most DOMS.

The best way to avoid DOMS is to train consistently.

You’ll almost certainly gets DOMS after you start a new workout program, especially one that causes a lot of muscle damage like running or lifting weights. After this initial “break-in” period, though, you shouldn’t experience much DOMS as long as you train a few times per week.

The only exception to this rule is if you make a significant change in your training program, which can also cause DOMS.

If you’re already dealing with DOMS, the best thing you can do is some light activity. While it won’t make a huge difference, easy cardio tends to help make DOMS go away faster than sitting around doing nothing.

What do you think about delayed-onset muscle soreness? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Ament W, Verkerke GJ. Exercise and fatigue. Sports Med. 2009;39(5):389-422. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939050-00005

- Noakes TD. The Limits of Human Endurance: What is the Greatest Endurance Performance of All Time? Which Factors Regulate Performance at Extreme Altitude? In: ; 2007:255-276. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-75434-5_20

- Brandner CR, Warmington SA. Delayed onset muscle soreness and perceived exertion after blood flow restriction exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(11):3101-3108. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001779

- Cheung K, Hume PA, Maxwell L. Delayed onset muscle soreness: Treatment strategies and performance factors. Sport Med. 2003;33(2):145-164. doi:10.2165/00007256-200333020-00005

- Schwane JA, Watrous BG, Johnson SR, Armstrong RB. Is Lactic Acid Related to Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness? Phys Sportsmed. 1983;11(3):124-131. doi:10.1080/00913847.1983.11708485

- Proske U, Morgan DL. Muscle damage from eccentric exercise: Mechanism, mechanical signs, adaptation and clinical applications. J Physiol. 2001;537(2):333-345. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00333.x

- Zourdos MC, Henning PC, Jo E, et al. Repeated Bout Effect in Muscle-Specific Exercise Variations. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(8):2270-2276. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000856

- Hough T. ERGOGRAPHIC STUDIES IN MUSCULAR FATIGUE AND SORENESS. J Boston Soc Med Sci. 1900;5(3):81-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19971340. Accessed September 9, 2019.

- Dupuy O, Douzi W, Theurot D, Bosquet L, Dugué B. An evidence-based approach for choosing post-exercise recovery techniques to reduce markers of muscle damage, Soreness, fatigue, and inflammation: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2018;9(APR). doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00403

- Fernandes JFT, Lamb KL, Twist C. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage and Recovery in Young and Middle-Aged Males with Different Resistance Training Experience. Sports. 2019;7(6):132. doi:10.3390/sports7060132

- Menzies P, Menzies C, McIntyre L, Paterson P, Wilson J, Kemi OJ. Blood lactate clearance during active recovery after an intense running bout depends on the intensity of the active recovery. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(9):975-982. doi:10.1080/02640414.2010.481721

- Gulick DT, Kimura IF, Sitler M, Paolone A, Kelly JD. Various treatment techniques on signs and symptoms of delayed onset muscle soreness. J Athl Train. 1996;31(2):145-152. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16558388. Accessed September 9, 2019.

- Cheung K, Hume P a, Maxwell L. Treatment Strategies and Performance Factors. Sport Med. 2003;33(2):145-164. doi:10.2165/00007256-200333020-00005