For many weightlifters, squats are the ultimate lower-body exercise.

During a set of heavy squats, it feels as though every muscle in your legs has to work in concert to lift the weight.

Is this true, though?

Some argue that, despite how hard squats seem, the exercise mainly trains the quads and glutes but does little for the hamstrings.

Furthermore, they claim that allowing your hamstrings to contribute to the squat makes the exercise more challenging. This, they say, is because your hamstrings work against your quads, preventing you from straightening your knees.

Does squatting work your hamstrings?

Or does using your hamstrings hinder squats?

Get evidence-based answers in this article.

Hamstring Anatomy

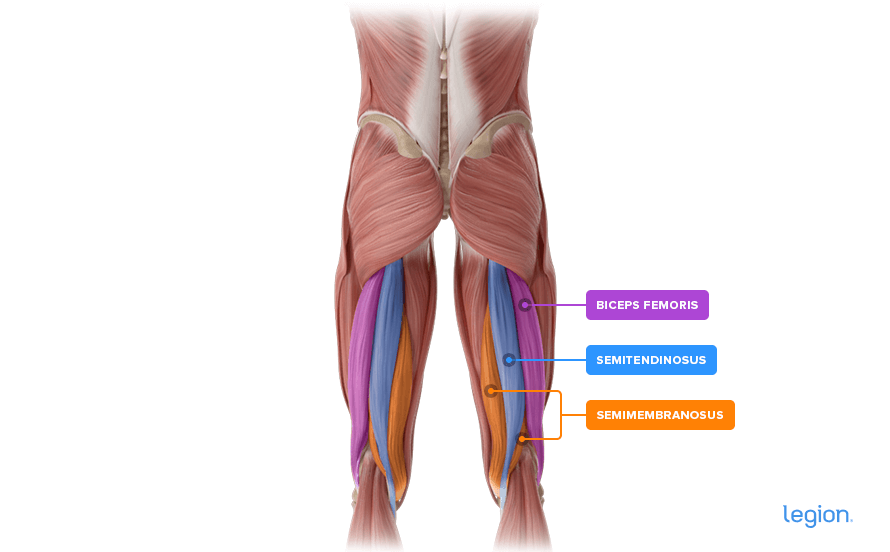

The hamstrings are a group of three muscles on the back of your thigh: The semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and the biceps femoris. Here’s how they look:

They’re biarticular, which means they cross two joints: The knee and hip. As such, the hamstrings contribute to movement at both the knees and hips.

Specifically, they’re responsible for knee flexion (bending your knees) and hip extension (moving your torso away from your thighs).

Do Squats Workout Your Hamstrings?

Many dub the squat the “king of exercises” because no other exercise simultaneously trains as many muscle groups across your entire body.

However, research shows they’re probably not as effective at training the hamstrings as many weightlifters believe.

Hamstring Activation in the Squat

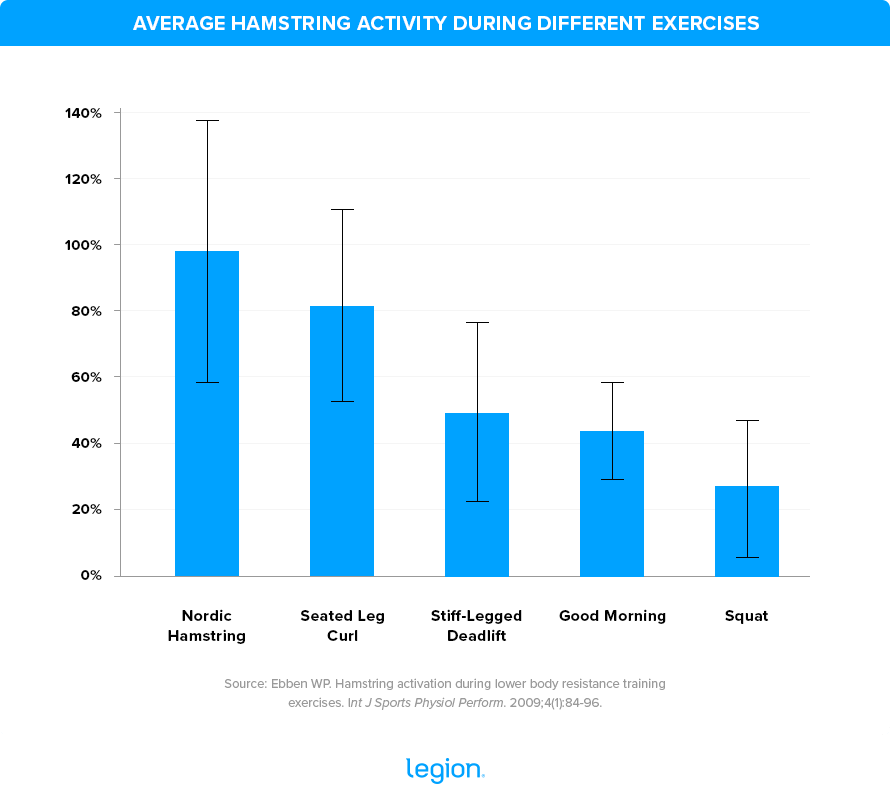

In a study published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, scientists measured leg muscle activity while athletes performed the following exercises:

- Barbell back squat

- Stiff-legged deadlift

- Single-leg stiff-legged deadlift

- Good morning

- Seated leg curl

- Nordic hamstring curl

The results showed that the hamstrings were least activated in the squat. This isn’t too surprising, given that the other exercises are specific hamstring exercises. However, according to these results, squats probably don’t activate the hamstrings enough to spur growth:

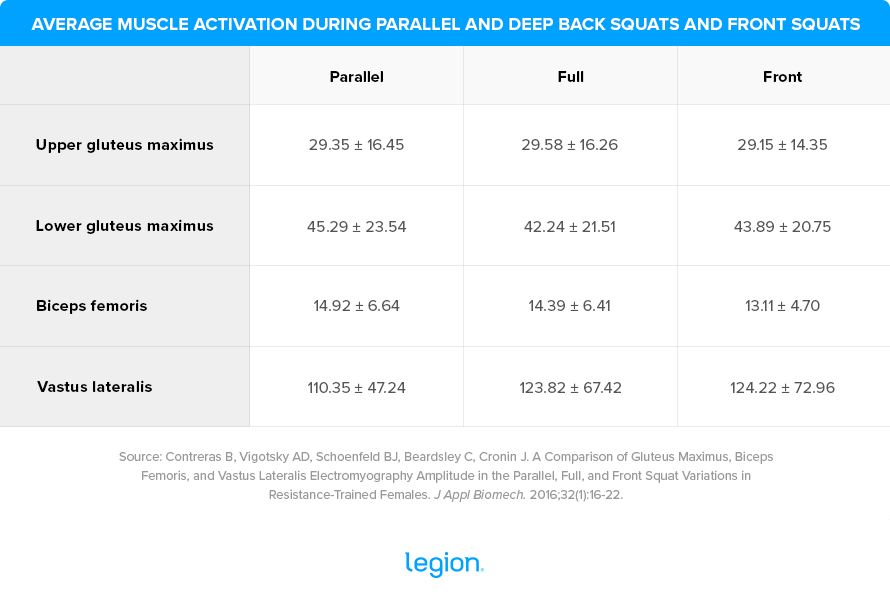

Similarly, a study conducted by scientists at Auckland University of Technology found that back and front squats elicited little hamstrings activation, especially compared to how much they trained the quads and glutes.

Note the difference between biceps femoris (a hamstring muscle) and vastus lateralis (a quad muscle) activation in this table from the study:

A common counter to this evidence is that while “shallow” squats might not sufficiently train your hamstrings, deep, full-range-of-motion squats (where you lower your body until your hips joints are below your knee joints) do.

Although some evidence suggests this may be true, other studies (including the study from the Auckland University of Technology above) show deep squats still aren’t enough to train your hamstrings effectively.

Another rejoinder is that muscle activation data only paints a partial picture. That is, it’s possible that hamstring activity is low in the squat, but that doesn’t mean you won’t grow big, strong hamstrings from squatting.

Fortunately, we can use research to analyze this claim as well . . .

Do Your Hamstring Muscles Grow From Squats?

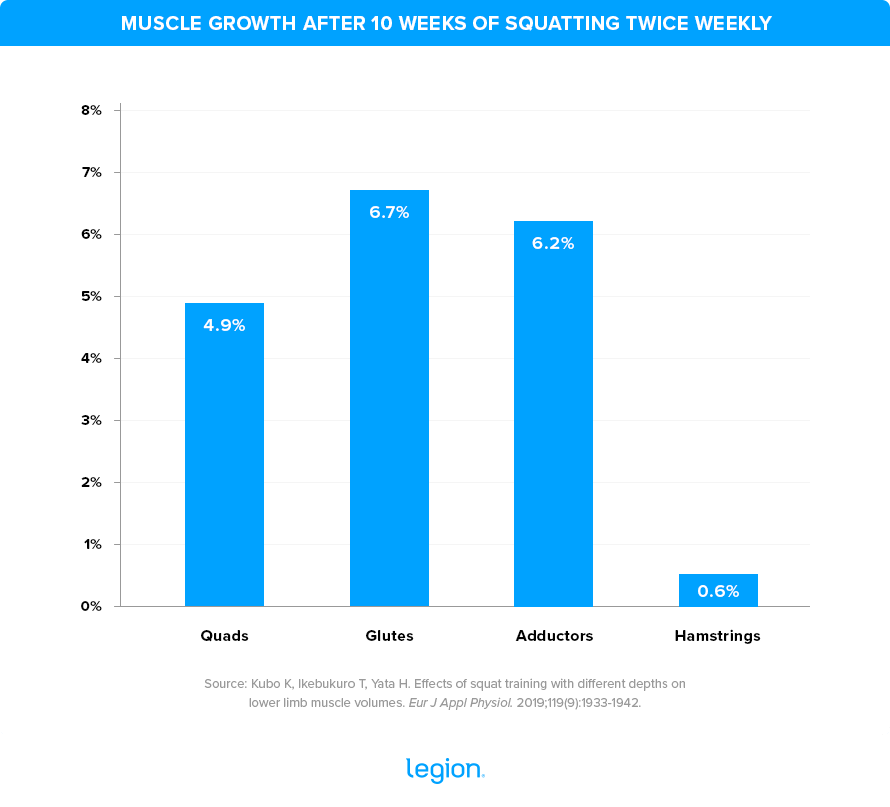

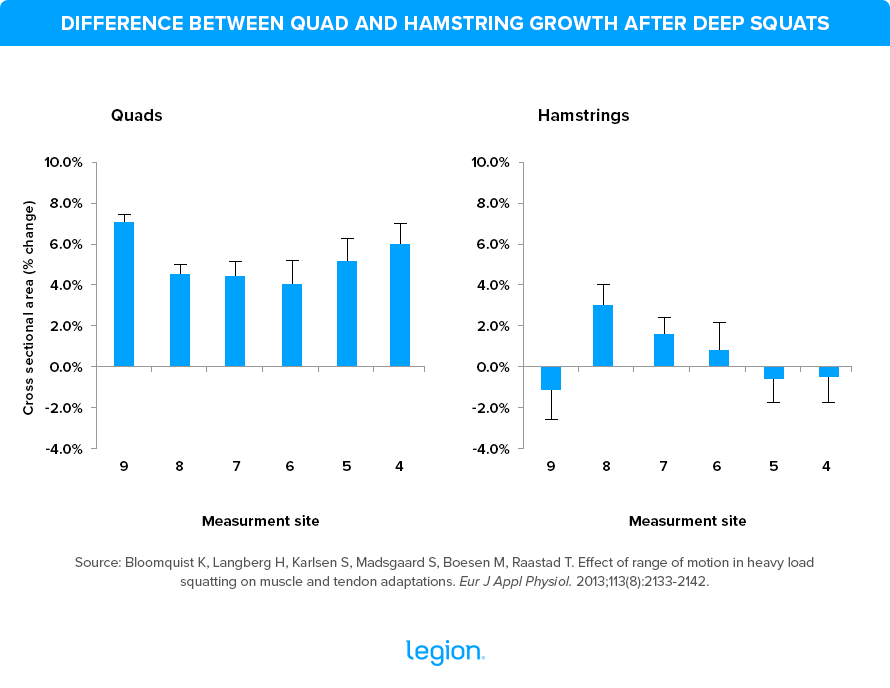

In a study published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology, weightlifters did 3 sets of 8 reps of squats twice weekly for 10 weeks, progressively adding weight as they grew stronger.

The researchers used MRI to measure muscle volume at the beginning and end of the squat training program and found that squats caused significant growth in the quads, glutes, and hip adductors (the muscles on the inside of your thighs that bring your legs together), but had minimal impact on the hamstrings.

Here’s a graph to illustrate:

In another study published in the same journal, researchers at Copenhagen University Hospital found that weightlifters following a 12-week squat training program saw a ~4-to-7%-increase in quad size but only a ~1-to-3%-increase in hamstring size:

In other words, squats are an excellent exercise for building beefy quads, glutes, and hip adductors, but they contribute minimally to hamstring growth.

The Hamstrings’ Role in the Squat

Many weightlifters believe that the hamstrings’ piddling contribution to the squat is a bad thing.

They think that if they can better leverage their hamstrings while squatting, they’ll be able to lift more weight.

While this is reasonable logic, it’s actually incorrect.

As we’ve already seen, the hamstrings cross your hip and knee joints and work to flex your knees and extend your hips. Thus, contracting the hamstrings pushes your hips forward in the squat (yay!) and bends your knees (boo!).

In other words, heavily involving your hamstrings in the squat makes squatting more challenging because they directly oppose the quads, which already have their work cut out straightening your knees.

To prevent your muscles from “fighting” against each other, your body preferentially recruits monoarticular muscles (those that only cross a single joint), such as the vasti muscles of the quads and the glutes.

Your body does this because these muscles work to straighten your knee and push your hips forward without inhibiting your ability to stand up (unlike the hamstrings).

How to Train Your Hamstring Optimally

Squatting may not be enough to train your hamstrings, but the following exercises are ideal for gaining hamstring strength and size:

- Deadlift

- Romanian Deadlift

- Leg Curl

- Nordic Hamstring Curl

- Good Morning

And if you want a training program that includes exercises like these, check out Mike’s fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger is right for you or if another strength training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Conclusion

Squats remain a top-tier exercise for training several major muscle groups across your entire body, especially your quads and glutes.

Nevertheless, squats aren’t the best exercise for training your hamstrings.

Therefore, including hamstring exercises in your training is essential for avoiding lower-body strength and size imbalances. Some good options are deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, leg curls, Nordic hamstring curls, and good mornings.

Scientific References +

- Ebben, William P. “Hamstring Activation during Lower Body Resistance Training Exercises.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, vol. 4, no. 1, Mar. 2009, pp. 84–96, https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.4.1.84.

- Contreras, Bret, et al. “A Comparison of Gluteus Maximus, Biceps Femoris, and Vastus Lateralis Electromyography Amplitude in the Parallel, Full, and Front Squat Variations in Resistance-Trained Females.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics, vol. 32, no. 1, 2016, pp. 16–22, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26252837, https://doi.org/10.1123/jab.2015-0113.

- ESCAMILLA, RAFAEL F. “Knee Biomechanics of the Dynamic Squat Exercise.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 33, no. 1, Jan. 2001, pp. 127–141, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200101000-00020.

- Cabral, Lissiane Almeida, et al. “Muscle Activation during the Squat Performed in Different Ranges of Motion by Women.” Muscles, vol. 2, no. 1, 12 Jan. 2023, pp. 12–22, https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles2010002. Accessed 14 Feb. 2023.

- ISEAR, JEROME A., et al. “EMG Analysis of Lower Extremity Muscle Recruitment Patterns during an Unloaded Squat.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 29, no. 4, Apr. 1997, pp. 532–539, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199704000-00016. Accessed 24 Feb. 2021.

- Jensen, Randall. “The Commons Hamstring Electromyographic Response of the Back Squat at Different Knee Angles during Eccentric and Concentric Phases Recommended Citation Jensen, RL. Hamstring Electromyographic Response of the Back Squat at Different Knee Angles during Eccentric and Concentric Phases.” Hamstring Electromyographic Response of the Back Squat at Different Knee Angles during Eccentric and Concentric Phases, vol. 1, 2000, pp. 158–161, commons.nmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=facwork_conferencepapers. Accessed 11 Jan. 2020.

- Bloomquist, K., et al. “Effect of Range of Motion in Heavy Load Squatting on Muscle and Tendon Adaptations.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 113, no. 8, 20 Apr. 2013, pp. 2133–2142, link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00421-013-2642-7, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-013-2642-7.

- Kubo, Keitaro, et al. “Effects of Squat Training with Different Depths on Lower Limb Muscle Volumes.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, 22 June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04181-y.

- Bryanton, Megan A., et al. “Quadriceps Effort during Squat Exercise Depends on Hip Extensor Muscle Strategy.” Sports Biomechanics, vol. 14, no. 1, 2 Jan. 2015, pp. 122–138, https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2015.1024716.