The dumbbell bench press is an upper-body exercise that involves lying on a bench and pressing dumbbells over your chest.

Like the barbell bench press, it trains all of your “pushing” muscles and allows you to handle heavy weights safely and progress regularly, which means it’s ideal for building muscle and gaining strength.

It also has a few advantages over the barbell bench press that make it worth periodically including in your workout routine.

In this article, you’ll learn what the dumbbell bench press is, how it compares to the barbell bench press, the benefits of the flat dumbbell bench press, how to dumbbell bench press with proper form, the best dumbbell bench press alternatives, and more.

Table of Contents

+

What Is the Dumbbell Bench Press?

The dumbbell bench press, or “flat dumbbell bench press,” is an upper-body free-weight exercise that involves lying on your back on a flat bench and pressing dumbbells above your chest.

The dumbbell bench press is identical to the barbell bench press in terms of technique, except you use dumbbells instead of a barbell.

Dumbbell vs. Barbell Bench Press

The flat barbell bench press is widely considered to be the best exercise for gaining chest muscle and pressing strength, and this is largely true.

You can lift 17% more weight when you bench press with a barbell than when you use dumbbells, which makes it one of the most effective ways to progressively overload your chest muscles.

That said, the dumbbell bench press is no slouch in this regard.

Research shows that the dumbbell bench press activates your pecs slightly more than the barbell bench press, which at least partially makes up for the fact you can’t lift as much weight.

That’s why it’s best not to think in terms of barbell or dumbbell bench press, and instead think in terms of barbell and dumbbell bench press (which is the approach I use in my best-selling fitness books Bigger Leaner Stronger for men, and Thinner Leaner Stronger for women).

Benefits of the Dumbbell Bench Press

1. It helps you train your muscles through a full range of motion.

Multiple studies show that muscles grow more when trained through a full range of motion, especially if they’re stretched as well.

The downside of the barbell bench press is that your range of motion is limited by the bar. That is, you have to stop each rep when the bar touches your chest, even though you could probably lower your hands a few more inches without a problem.

You don’t have that restriction when using dumbbells. This means you can train your muscles through a greater range of motion and stretch your pecs more thoroughly in each rep.

That isn’t to say the dumbbell bench press is superior to the barbell bench press, though. Your pecs get plenty stretched in the barbell bench press if you use proper form, and as we’ve already seen, the barbell bench press allows you to lift more weight than the dumbbell version, which is generally better for muscle and strength gain.

All in all, it’s best to use the dumbbell bench press as an accessory exercise to the barbell bench press, and you should include both in your program if you want to maximize chest growth.

2. It helps to correct muscle imbalances.

In the dumbbell bench press, both sides of your body must lift the same amount of weight independently.

This is beneficial because it helps you identify and correct muscle and strength imbalances because one side can’t “take over” or “pick up slack” from the other, which often happens in the barbell bench press.

3. It helps you to train around injuries.

Dumbbell exercises allow your limbs to move more freely than many barbell exercises, which enables you to slightly alter your movements to avoid pain.

For example, your wrists are locked in the same position during the barbell bench press. But during the dumbbell bench press, you can rotate them into a more comfortable position.

This is particularly helpful when trying to “train around” an injury, such as a wrist sprain, shoulder niggle, or elbow tendinitis.

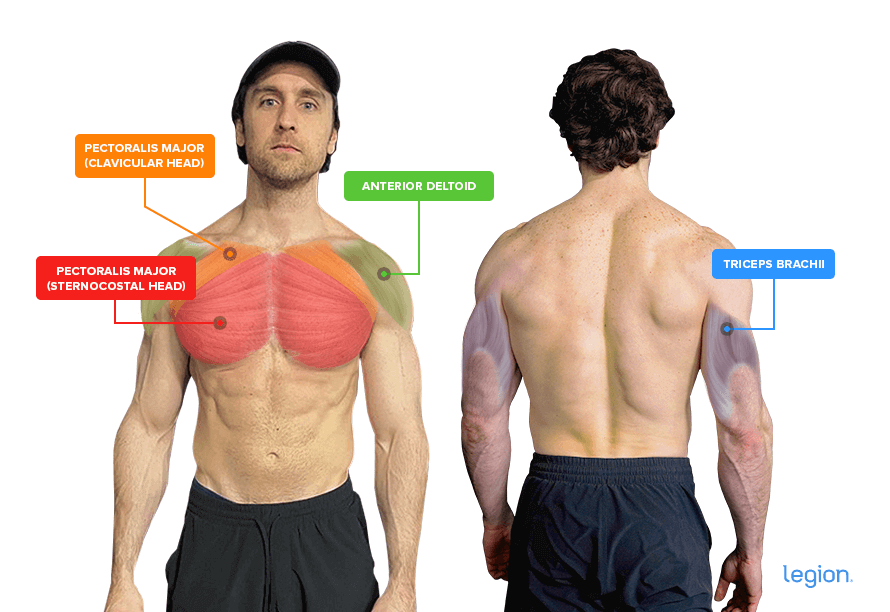

Dumbbell Bench Press: Muscles Worked

The dumbbell bench press trains all of your upper-body “pushing” muscles, including the . . .

- Pectoralis major (both the sternocostal and clavicular heads)

- Anterior deltoid

- Triceps brachii

Here’s what the muscles worked by the dumbbell press look like on your body:

How to Dumbbell Bench Press

The best way to learn proper dumbbell bench press form is to break it into three parts: set up, press, and descend.

1. Set Up

Grab a dumbbell in each hand, sit on a flat bench, and rest the dumbbells on your thighs.

Lie back and hoist the dumbbells up by giving them a nudge with your thighs so that you hold them on either side of your chest.

Arch your back slightly, plant your feet on the floor, raise your chest, and tuck your shoulder blades down and squeeze them together. A good cue is to think of pulling your shoulder blades into your back pockets like this:

2. Press

Press the dumbbells toward the ceiling. As they rise, allow the weights to drift closer together (some people like to touch them at the top of each rep, but this isn’t necessary). At the top of the rep your elbows should be almost locked and the dumbbells should be 1-to-2 inches apart or barely touching.

Keep your shoulder blades “down and back,” your elbows about 6-to-12 inches from your torso, your lower back slightly arched, your butt on the bench, and your feet on the floor.

3. Descend

Reverse the movement and lower the dumbbells to either side of your chest.

You should feel a deep stretch in your pecs and the handles of the dumbbells should be in line with your nipples.

The Best Dumbbell Bench Press Alternatives

1. Single-Arm Dumbbell Bench Press

The main benefits of the one-arm dumbbell bench press are it allows you to focus on each side of your body separately, which helps you develop a greater “mind-muscle connection.” It also trains your core muscles, which have to work hard to prevent your body from twisting.

Because the one-arm dumbbell bench press is inherently unstable, though, you have to significantly reduce the amount of weight you lift, which limits the muscle-building potential of the exercise.

2. Dumbbell Floor Press

The dumbbell floor press is a dumbbell bench press variation that involves lying on the floor instead of a bench. This shortens the exercise’s range of motion (you can’t lower your elbows as far as you do in the regular dumbbell bench press because they run into the floor) and makes it less effective at training your pecs.

That said, it is effective for training your triceps, which are largely responsible for “locking out” your elbows at the top of each rep, and it’s a viable dumbbell bench press variation if you don’t have access to a bench.

3. Alternating Dumbbell Bench Press

The main reason for doing the alternating dumbbell bench press is that the arm that isn’t pressing gets a short rest between each rep, which should hypothetically allow you to use slightly heavier weights or do an extra couple of reps.

The downside of this exercise is that even when your arms are “resting” they’re still supporting the weight, so you may find that you fatigue sooner with this approach.

The alternating dumbbell bench press also requires more coordination and balance than the regular dumbbell bench press, which means some people find it difficult to perform correctly.

FAQ #1: Dumbbell Press vs. Bench Press: Which is better?

Neither exercise is better or worse than the other. Both exercises train the same muscles to a similar degree, so you can use them interchangeably in your workouts.

The benefits of the dumbbell bench press are that it allows you to train through a larger range of motion, which is beneficial for muscle growth, and it may be more comfortable for some people.

One drawback of the dumbbell bench press is that it doesn’t allow you to lift as much weight as the barbell bench press, which means the barbell variation is superior for gaining absolute strength.

Of course, there’s no reason to choose just one. The best solution for most people is to include both exercises in your program.

This is how I personally like to organize my training, and it’s similar to the method I advocate in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

FAQ #2: Are there accurate dumbbell bench press standards to aim for?

One rule of thumb you’ll often hear for a good dumbbell bench press standard is that you should be able to dumbbell bench press 80% of your barbell bench press (that’s including both dumbbells).

For example, if you barbell bench press 200 pounds, you should be able to dumbbell bench press 160 pounds (80 pounds in each hand).

If you don’t do much barbell bench pressing, though, then use these guidelines instead:

Dumbbell bench press standards for men:

- Beginner: 0.6 times your body weight

- Intermediate: 0.9 times your body weight

- Advanced: 1.2 times your body weight

Dumbbell bench press standards for women:

- Beginner: 0.3 times your body weight

- Intermediate: 0.5 times your body weight

- Advanced: 0.7 times your body weight

Note: With these standards, “Beginner” refers to anyone who’s been consistently training for 6-to-12 months, “Intermediate” refers to anyone who’s been consistently training for 1-to-3 years, and “Advanced” refers to anyone who’s been consistently training for more than 3 years. All strength standards refer to the minimum total weight (both dumbbells’ weight combined) you should be able to press for a single rep (one-rep max).

FAQ #3: Is it possible to make a dumbbell vs. barbell bench press weight comparison?

It’s difficult to make a precise dumbbell to barbell bench press conversion, but you can estimate your max barbell bench press weight based on your max dumbbell bench press weight using the results of a study conducted by scientists at Sogn og Fjordane University College.

In this study, the researchers found that, on average, people could lift just under 20% more weight on the barbell bench press than they could on the dumbbell bench press.

This means that if you could do one rep on the dumbbell bench press with dumbbells weighing 80 pounds each (160 pounds total), you’ll likely be able to do one rep on the barbell bench press with around 200 pounds.

Scientific References +

- Saeterbakken, A. H., van den Tillaar, Ro., & Fimland, M. S. (2011). A comparison of muscle activity and 1-RM strength of three chest-press exercises with different stability requirements. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(5), 533–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.543916

- Farias, D. D. A., Willardson, J. M., Paz, G. A., Bezerra, E. D. S., & Miranda, H. (2017). Maximal Strength Performance and Muscle Activation for the Bench Press and Triceps Extension Exercises Adopting Dumbbell, Barbell, and Machine Modalities Over Multiple Sets. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(7), 1879–1887. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001651

- Bloomquist, K., Langberg, H., Karlsen, S., Madsgaard, S., Boesen, M., & Raastad, T. (2013). Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(8), 2133–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-013-2642-7

- Kubo, K., Ikebukuro, T., & Yata, H. (2019). Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2019 119:9, 119(9), 1933–1942. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-019-04181-Y

- Pinto, R. S., Gomes, N., Radaelli, R., Botton, C. E., Brown, L. E., & Bottaro, M. (2012). Effect of range of motion on muscle strength and thickness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(8), 2140–2145. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E31823A3B15

- McMahon, G. E., Onambélé-Pearson, G. L., I. Morse, C., Burden, A. M., & Winwood, K. (2013). How Deep Should You Squat to Maximise a Holistic Training Response? Electromyographic, Energetic, Cardiovascular, Hypertrophic and Mechanical Evidence. Electrodiagnosis in New Frontiers of Clinical Research. https://doi.org/10.5772/56386

- Saeterbakken, A. H., van den Tillaar, Ro., & Fimland, M. S. (2011). A comparison of muscle activity and 1-RM strength of three chest-press exercises with different stability requirements. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(5), 533–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.543916

- BaJ, J. S., Baker, S., Davies, B., Cooper, S. M., Wong, D. P., Buchan, D. S., Kilgoreker, L., Davies, B., Cooper, S. M., Wong, D. P., Buchan, D. S., & Kilgore, L. (n.d.). Strength and body composition changes in recreationally strength-trained individuals: comparison of one versus three sets resistance-training programmes. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24083231/