Key Takeaways

- Many people say that eating more of your calories at night slows down weight loss, whereas eating more calories in the morning speeds up weight loss.

- The vast majority of studies show that skipping breakfast or eating most of your calories in the evening doesn’t cause weight gain or interfere with weight loss one bit.

- Keep reading to learn exactly how eating at night affects your metabolism, ability to lose weight, hunger levels, and more!

Poke around online for weight loss tips, and you’ll invariably come across the idea that you shouldn’t eat at night.

Why?

Proponents of this idea usually claim that your metabolism doesn’t work as well at night, and thus any calories you eat are more likely to be stored as fat instead of being burned for energy.

Sounds … kind of scien-y-ish … but is it true?

Does your metabolism really slow down as the day drags on?

Are calories eaten in the evening inherently more fattening than calories eaten in the morning?

Can eating more calories in the morning and fewer calories in the evening really help you lose weight?

You’ll learn the answers to all of these questions in this article.

You’ll learn exactly why people think eating at night makes you gain weight, what really causes weight gain (hint: it’s not eating at night), and what science actually says about how late-night eating affects your metabolism.

Let’s get to it!

Why Do People Think Eating at Night Makes You Gain Weight?

For years, personal trainers, weight loss gurus, and Internet (not) doctors have claimed that your metabolism is fastest early in the morning and gradually slows throughout the day before bottoming out in the evening.

Thus, they claim, you should eat more calories in the morning and fewer calories in the evening to avoid fat gain.

This idea is summed up in the old saw that states, “Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper.”

Is this true, though?

Does your body really burn fewer calories in the evening?

And if so, does this mean eating more calories in the evening will make you gain more body fat?

Before we go any further, let’s first define what metabolism means.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines metabolism as follows:

The chemical processes that occur within a living organism in order to maintain life.

Two kinds of metabolism are often distinguished: constructive metabolism, or anabolism, the synthesis of the proteins, carbohydrates, and fats that form tissue and store energy; and destructive metabolism, or catabolism, the breakdown of complex substances and the consequent production of energy and waste matter.

In other words, when we say metabolism, what we mean is the body’s ability to use various chemical processes to produce, maintain, and break down various substances, and to make energy available for cells to use.

So, what does it mean to have a slow or fast metabolism?

These distinctions refer to what’s known as your body’s metabolic rate, which is the total amount of energy the body uses in a single day to perform the many functions involved in metabolism.

Generally, when people speak of your metabolism, they’re talking about your basal metabolic rate (BMR), which is how many calories your body requires to stay alive (not including physical activity).

Thus, when someone says your metabolism is “slow,” they generally mean your BMR is lower than normal, and if they say your metabolism is “fast,” they mean your BMR is higher than normal.

So, is it true that your metabolism (BMR) naturally slows throughout the day?

Well, no.

What’s more, even if it did, this wouldn’t make eating at night more fattening than eating earlier in the day.

Why not?

First of all, research conducted by scientists at the USDA shows that BMR doesn’t change significantly while you sleep, much less in the evening hours before you sleep. That is, your BMR is the same in the morning, afternoon, evening, and even while you sleep.

In fact, some research conducted by scientists at Columbia University shows that in people who are a healthy weight, BMR actually increases slightly while you sleep.

Second, let’s play Devil’s advocate and say that your metabolism does slightly decrease throughout the day. Would this even matter?

No, it wouldn’t.

The reason for this is that your body fat stores are dictated by what’s known as energy balance, which can be expressed by this simple equation:

Energy In – Energy Out = Energy Balance

When Energy In exceeds Energy Out over a period of time, you’re consuming more calories than you’re burning, which means you’re maintaining a calorie surplus. When you stay in a calorie surplus for days, weeks, and months, you gain body fat.

The reverse is also true.

When Energy Out exceeds Energy In over a period of time, you’re consuming fewer calories than you’re burning, which means you’re maintaining a calorie deficit. When you stay in a calorie deficit for days, weeks, and months, you lose body fat.

Here’s the kicker:

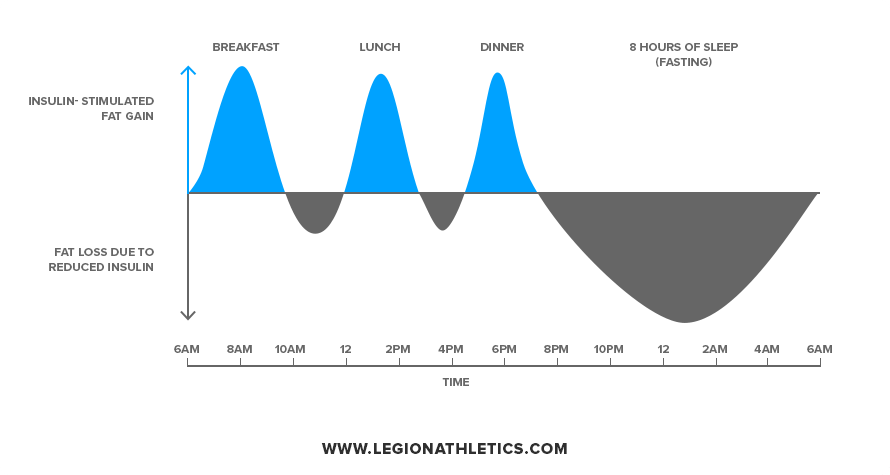

After every meal, your body burns some calories for immediate energy and stores some in the form of body fat (researchers refer to this as the post-prandial state). After your body finishes digesting your meal, it relies on body fat stores to meet its energy needs until the next meal (researchers call this the post-absorptive state).

You switch between these two states throughout the day, gaining a little fat here, losing some there, and for most people, these little ebbs and flows in fat gain even out by the end of the day. That is, although you gain fat after meals and lose it between meals, the net result is a wash.

Here’s a chart that illustrates this nicely:

The blue portions are the periods where your body has excess energy due to food having been eaten. The gray portions are the periods when the body has no energy left from food and thus has to burn fat to stay alive.

You can think of your body fat stores like a checking account. Every time you eat a meal, you make a deposit, and every time you go a few hours between meals (including when you sleep), you make a withdrawal.

Whether or not you gain weight, then, depends on whether or not you’re making more deposits or withdrawals over time. When you make those deposits or withdrawals throughout the day is irrelevant.

So long as your average calorie intake over a period of time is more or less equal to your average calorie expenditure over a period of time, you’ll stay the same weight no matter when you eat those calories throughout the day.

(Oh, and if you feel confused about how many calories you should eat to reach your goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz to learn exactly what diet is right for you.)

Finally, here’s one more reason to ignore this malarkey about your metabolism slowing down in the evening: if you work out in the evening, you’ll burn far more calories than you would in the morning.

In other words, even if your BMR decreased throughout the day, and if this resulted in more fat gain in the evening, you could work around this issue by intentionally working out in the evening.

Not that this matters, since your metabolism most definitely doesn’t slow down in the evening, but it’s another needle in the balloon of “eating at night makes you gain weight no matter what.”

The bottom line is that your BMR hums along at more or less the same pace at all times, which makes perfect sense when you think about it. Your brain, liver, kidneys, and other organs (which are responsible for the majority of your BMR) need just as much energy from 9 to 10 p.m. as they do from 9 to 10 a.m., after all.

Summary: Your metabolism isn’t slower in the evening than it is in the morning, and even if it was, calories eaten at night still wouldn’t be more fattening than calories eaten earlier in the day.

What Science Really Says About Eating at Night

So, you know your metabolism doesn’t really slow down in the evening, and you know that calories eaten at night aren’t inherently more fattening than calories eaten earlier in the day.

In other words, weight gain and weight loss still boils down to calories in versus calories out.

And at this point you may be wondering, are there any benefits to eating less at night?

Well, some studies suggest there might be.

Specifically, some research shows that eating more calories earlier in the day may help increase what’s known as the thermic effect of food, or how many calories your body burns digesting the calories you consume.

The best example of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at the University of Lubeck, where researchers split sixteen healthy, non-obese participants into two groups:

1. A large-breakfast group that consumed the majority of their total daily calories at breakfast and had a moderate size lunch and a small dinner.

Specifically, they consumed 69 percent of their calories at breakfast, 20 percent at lunch, and 11 percent at dinner.

2. A large-dinner group that consumed the majority of their total daily calories at dinner and had a moderate size lunch and a small breakfast.

Specifically, they consumed 11 percent of their calories at breakfast, 20 percent at lunch, and 69 percent at dinner.

Both groups followed this protocol while under strict supervision in a lab. They consumed the same number of calories and the same amount of protein, carbs, and fat, and didn’t exercise during the study.

The only difference between the two groups was whether they ate the majority of their calories in the morning or the evening.

The researchers measured the participant’s energy expenditure before and after both breakfast and dinner on each day of the study, and then averaged the results to see which eating schedule produced the highest TEF over the course of the study.

They also took various blood samples from the participant’s throughout the day to measure their blood sugar, insulin, and other hormones, and measured the participant’s level of hunger and desire for sweets before each meal and several hours after dinner.

The result?

The large-breakfast group experienced over twice as much TEF as the large-dinner group, which would work out to around 50 to 100 calories per day.

The large-breakfast group was also less hungry during the day and had fewer cravings for sweets five hours after breakfast and immediately before dinner than the large-dinner group.

In the large-dinner group, hunger actually increased after breakfast (remember, they were eating a very small breakfast) and only declined significantly after dinner. In the large-breakfast group, hunger declined significantly after breakfast, leveled off throughout the day, and then declined further after dinner.

So, what to make of these results?

First of all, this study shows that eating a large breakfast may increase your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) more than eating a large dinner. Over time, this could lead to more weight loss while eating the same number of calories overall.

Second, this study indicates you may experience less hunger and cravings throughout the day if you eat a hearty breakfast.

Before you rejigger your meal plan, though, it’s worth considering a few caveats.

First, if you’re already eating a large breakfast, then it’s not clear if eating even more calories earlier in the day will have additional benefits.

For example, if you’re already eating 800 calories in the morning, it’s not clear if eating 1,200 or 1,500 might help you burn proportionately more calories via TEF than if you ate those calories in the evening.

Second, this study wasn’t really a true apples to apples comparison between the TEF of breakfast and dinner.

We don’t need to get into the nitty gritty details of the study design, but the long story short is that TEF was reported in terms of a percentage increase from baseline—not total number of calories burned.

The reason this matters is because the large-breakfast group was consuming most of their calories after an overnight fast, which means their baseline TEF levels would be near rock bottom. The large-dinner group, though, was eating most of their calories after already eating breakfast and lunch, which means their TEF was probably elevated slightly to begin with.

Thus, it’s possible the reason the large-dinner group experienced a smaller relative increase in TEF is because their TEF levels were already higher to begin with.

Think of it this way: imagine you’re already driving at 30 miles per hour (mph), and then you accelerate to 60 mph (increasing your speed by 30 mph). Then, another driver who’s parked nearby accelerates to 60 mph (increasing their speed by 60 mph).

Who’s going faster?

Neither of you! You’re going the same speed, but the other driver experienced a larger percentage increase in their speed than you.

It’s possible the same thing happened in this study—TEF was already higher in the large-dinner group, and thus the percentage increase was smaller than that of the large-breakfast group.

Here’s what this all means: it’s possible that both groups actually burned the same absolute number of calories from TEF, but the large-breakfast group simply experienced a larger percentage increase in calorie burning after eating their morning meal.

Another limitation to this study is that the participants weren’t exercising, which means we don’t know if the results would apply to people who exercise regularly. Research shows that exercise may increase TEF regardless of when you eat, and it also has positive effects on appetite, which could have affected the results.

Finally, it’s also possible that the reason the large-dinner group experienced less TEF is that they weren’t used to eating such a large dinner.

Another study conducted by scientists at the University of Nottingham found that following a consistent meal schedule can boost TEF and following an irregular meal schedule can decrease TEF. Thus, it’s possible that once the people in the large-dinner group became accustomed to eating more of their calories in the evening, they would have experienced just as much TEF as the large-breakfast group.

There’s another reason to doubt eating in the morning is inherently better than eating in the evening:

This popular strategy usually involves skipping breakfast and eating most of your calories later in the day, and research shows it’s just as effective at promoting weight loss as diets that include breakfast.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at Kennesaw State University had twenty-six young, active men maintain a high-protein, calorie-restricted diet and follow a strength training program for four weeks. Half of the participants consumed all of their calories from around noon to eight p.m. (skipping breakfast, basically), and the other half followed a normal meal schedule.

After four weeks, both groups lost the same amount of fat, gained the same amount of strength and muscle, and experienced the same level of hunger throughout the study.

Other studies on intermittent fasting conducted by scientists at Texas Tech University and the University of Sydney have found more or less the same thing: eating breakfasting doesn’t improve weight loss, and skipping breakfast and eating more calories in the evening doesn’t interfere with weight loss.

Just to drive a few more nailed into this coffin, two other studies, one conducted by scientists at the University of Chieti and one conducted by scientists at the University of São Paulo found that obese people who ate all of their calories for breakfast, all of their calories for dinner, or spread their calories across multiple meals throughout the day, all lost the same amount of weight.

So, what does this all mean?

Eating more calories in the morning might increase energy expenditure and decrease cravings, but these effects don’t seem to be significant (and may not exist at all or at least in all situations).

All in all, how much you eat over the long-term is going to have a much larger effect on your body composition than when you eat.

More specifically …

- Eating more calories in the morning instead of the evening won’t make you lose weight by itself—you have to maintain a calorie deficit to lose weight.

- If you’re already in a calorie deficit, eating more calories in the morning may help you burn a few more calories per day and feel less hungry, but it’s still not clear how effective this strategy really is (or if it works at all).

- If you’re eating enough calories to maintain your weight, eating more calories in the evening won’t make you gain weight.

Summary: Eating more calories in the morning may slightly increase energy expenditure and reduce hunger, but it’s still not clear how effective this strategy really is (or if it works at all). Most studies show that when you eat your calories doesn’t matter when it comes to weight loss.

The Bottom Line on Eating at Night

Although many people believe their metabolisms slow down throughout the day and that calories eaten at night are inherently more fattening than calories eaten in the morning, this isn’t true.

Your metabolism (really, your BMR), is more or less the same at all times of the day. Even if your BMR dropped in the evening, calories eaten at night wouldn’t magically become more fattening.

The only way to gain weight is to maintain a calorie surplus over time, and when you eat those calories throughout the day is more or less irrelevant as far as your body is concerned.

Although a few studies have shown that eating more calories in the morning may slightly boost metabolic rate, there are a few problems with this research that makes it hard to say how effective this strategy really is.

Moreover, the vast majority of studies have shown that skipping breakfast altogether or eating more calories in the evening has no impact on weight or fat loss.

That is, people who eat most (or even all) of their calories in the evening lose just as much weight as people who eat more or all of their calories in the morning.

So, circling back to the original question: does eating at night make you gain weight?

No, absolutely not.

Eating too many calories over time makes you gain weight, which is why controlling your calorie intake is the single most important thing you can do to lose weight or avoid weight gain.

If you want to learn more about how your calorie intake influences your body composition and how to control your calorie intake to lose weight, maintain your weight, or build muscle, check out these articles:

How Many Calories You Should Eat (with a Calculator)

This Is the Best Macronutrient Calculator on the Net

The Definitive Guide to Effective Meal Planning

How to Lose Weight Faster in 5 Simple Steps

The Ultimate Guide to Bulking Up (Without Just Getting Fat)

What’s your take on late-night eating? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Jakubowicz, D., Barnea, M., Wainstein, J., & Froy, O. (2013). High Caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity, 21(12), 2504–2512. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20460

- Morris, C. J., Garcia, J. I., Myers, S., Yang, J. N., Trienekens, N., & Scheer, F. A. J. L. (2015). The human circadian system has a dominating role in causing the morning/evening difference in diet-induced thermogenesis. Obesity, 23(10), 2053–2058. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21189

- Lee, S. J., & Kim, Y. M. (2013). Effects of exercise alone on insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in obese youth. Diabetes and Metabolism Journal, 37(4), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2013.37.4.225

- Dorling, J., Broom, D. R., Burns, S. F., Clayton, D. J., Deighton, K., James, L. J., King, J. A., Miyashita, M., Thackray, A. E., Batterham, R. L., & Stensel, D. J. (2018). Acute and chronic effects of exercise on appetite, energy intake, and appetite-related hormones: The modulating effect of adiposity, sex, and habitual physical activity. In Nutrients (Vol. 10, Issue 9). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091140

- Farshchi, H. R., Taylor, M., & Macdonald, I. A. (2004). Decreased thermic effect of food after an irregular compared with a regular meal pattern in healthy lean women. International Journal of Obesity, 28(5), 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802616

- Richter, J., Herzog, N., Janka, S., Baumann, T., Kistenmacher, A., & Oltmanns, K. M. (2020). Twice as High Diet-Induced Thermogenesis After Breakfast vs Dinner On High-Calorie as Well as Low-Calorie Meals. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 105(3). https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz311

- Snijders, T., Res, P. T., Smeets, J. S., van Vliet, S., van Kranenburg, J., Maase, K., Kies, A. K., Verdijk, L. B., & van Loon, L. J. (2015). Protein Ingestion before Sleep Increases Muscle Mass and Strength Gains during Prolonged Resistance-Type Exercise Training in Healthy Young Men. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(6), 1178–1184. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.208371

- Res, P. T., Groen, B., Pennings, B., Beelen, M., Wallis, G. A., Gijsen, A. P., Senden, J. M. G., & Van Loon, L. J. C. (2012). Protein ingestion before sleep improves postexercise overnight recovery. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 44(8), 1560–1569. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31824cc363

- Groen, B. B. L., Res, P. T., Pennings, B., Hertle, E., Senden, J. M. G., Saris, W. H. M., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2012). Intragastric protein administration stimulates overnight muscle protein synthesis in elderly men. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 302(1). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00321.2011

- Scheer, F. A. J. L., Hilton, M. F., Mantzoros, C. S., & Shea, S. A. (2009). Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(11), 4453–4458. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0808180106

- Jakubowicz, D., Barnea, M., Wainstein, J., & Froy, O. (2013). High Caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity, 21(12), 2504–2512. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20460

- Reid, K. J., Baron, K. G., & Zee, P. C. (2014). Meal timing influences daily caloric intake in healthy adults. Nutrition Research, 34(11), 930–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2014.09.010

- Garaulet, M., Gómez-Abellán, P., Alburquerque-Béjar, J. J., Lee, Y. C., Ordovás, J. M., & Scheer, F. A. J. L. (2013). Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. International Journal of Obesity, 37(4), 604–611. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.229

- Sofer, S., Eliraz, A., Kaplan, S., Voet, H., Fink, G., Kima, T., & Madar, Z. (2011). Greater weight loss and hormonal changes after 6 months diet with carbohydrates eaten mostly at dinner. Obesity, 19(10), 2006–2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.48

- Reid, K. J., Baron, K. G., & Zee, P. C. (2014). Meal timing influences daily caloric intake in healthy adults. Nutrition Research, 34(11), 930–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2014.09.010

- BA, S., I, C., JC, S., & WPT, J. (2004). Diet, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutrition, 7(1a), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2003585

- Hand, G. A., Shook, R. P., Paluch, A. E., Baruth, M., Crowley, E. P., Jaggers, J. R., Prasad, V. K., Hurley, T. G., Hebert, J. R., O’Connor, D. P., Archer, E., Burgess, S., & Blair, S. N. (2013). The energy balance study: The design and baseline results for a longitudinal study of energy balance. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 84(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.816224

- Romieu, I., Dossus, L., Barquera, S., Blottière, H. M., Franks, P. W., Gunter, M., Hwalla, N., Hursting, S. D., Leitzmann, M., Margetts, B., Nishida, C., Potischman, N., Seidell, J., Stepien, M., Wang, Y., Westerterp, K., Winichagoon, P., Wiseman, M., & Willett, W. C. (2017). Energy balance and obesity: what are the main drivers? Cancer Causes and Control, 28(3), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-017-0869-z

- Baron, K. G., Reid, K. J., Horn, L. Van, & Zee, P. C. (2013). Contribution of evening macronutrient intake to total caloric intake and body mass index. Appetite, 60(1), 246–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.026

- Baron, K. G., Reid, K. J., Kern, A. S., & Zee, P. C. (2011). Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity, 19(7), 1374–1381. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.100

- Nonino-Borges, C. B., Martins Borges, R., Bavaresco, M., Suen, V. M. M., Moreira, A. C., & Marchini, J. S. (2007). Influence of meal time on salivary circadian cortisol rhythms and weight loss in obese women. Nutrition, 23(5), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2007.02.007

- Sensi, S., & Capani, F. (1987). Chronobiological aspects of weight loss in obesity: Effects of different meal timing regimens. Chronobiology International, 4(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528709078532

- Seimon, R. V., Roekenes, J. A., Zibellini, J., Zhu, B., Gibson, A. A., Hills, A. P., Wood, R. E., King, N. A., Byrne, N. M., & Sainsbury, A. (2015). Do intermittent diets provide physiological benefits over continuous diets for weight loss? A systematic review of clinical trials. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 418, 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.014

- Tinsley, G. M., Forsse, J. S., Butler, N. K., Paoli, A., Bane, A. A., La Bounty, P. M., Morgan, G. B., & Grandjean, P. W. (2017). Time-restricted feeding in young men performing resistance training: A randomized controlled trial†. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2016.1223173

- Stratton, M. T., Tinsley, G. M., Alesi, M. G., Hester, G. M., Olmos, A. A., Serafini, P. R., Modjeski, A. S., Mangine, G. T., King, K., Savage, S. N., Webb, A. T., & Vandusseldorp, T. A. (2020). Four Weeks of Time-Restricted Feeding Combined with Resistance Training Does Not Differentially Influence Measures of Body Composition, Muscle Performance, Resting Energy Expenditure, and Blood Biomarkers. Nutrients, 12(4), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041126

- Farshchi, H. R., Taylor, M., & Macdonald, I. A. (2004). Decreased thermic effect of food after an irregular compared with a regular meal pattern in healthy lean women. International Journal of Obesity, 28(5), 653–660. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802616

- Dorling, J., Broom, D. R., Burns, S. F., Clayton, D. J., Deighton, K., James, L. J., King, J. A., Miyashita, M., Thackray, A. E., Batterham, R. L., & Stensel, D. J. (2018). Acute and chronic effects of exercise on appetite, energy intake, and appetite-related hormones: The modulating effect of adiposity, sex, and habitual physical activity. In Nutrients (Vol. 10, Issue 9). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091140

- Denzer, C. M., & Young, J. C. (2003). The effect of resistance exercise on the thermic effect of food. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(3), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.13.3.396

- Richter, J., Herzog, N., Janka, S., Baumann, T., Kistenmacher, A., & Oltmanns, K. M. (2020). Twice as High Diet-Induced Thermogenesis After Breakfast vs Dinner On High-Calorie as Well as Low-Calorie Meals. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 105(3). https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz311

- Morris, C. J., Garcia, J. I., Myers, S., Yang, J. N., Trienekens, N., & Scheer, F. A. J. L. (2015). The human circadian system has a dominating role in causing the morning/evening difference in diet-induced thermogenesis. Obesity, 23(10), 2053–2058. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21189

- Zhang, K., Sun, M., Werner, P., Kovera, A. J., Albu, J., Pi-Sunyer, F. X., & Boozer, C. N. (2002). Sleeping metabolic rate in relation to body mass index and body composition. International Journal of Obesity, 26(3), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801922

- Seale, J. L., & Conway, J. M. (1999). Relationship between overnight energy expenditure and BMR measured in a room-sized calorimeter. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600685