Key Takeaways

- The reason exercise doesn’t always help people lose weight is because people often use it as a license to overeat—not because exercise makes you uncontrollably hungry.

- Research shows that exercise helps you stay fuller on less food, lose fat faster, and preserve or even gain muscle while losing fat.

- If you combine strength training and a small amount of cardio with proper dieting principles, you’ll get much better results than if you were to focus on diet or exercise alone.

“Exercise won’t make you thin.”

“Exercise won’t help you lose weight.”

“You shouldn’t exercise to lose weight.”

Headlines like these are popping up more and more nowadays.

Open up the articles and you’ll find they all tell more or less the same story:

You go for a 30-minute run and burn 300 calories.

You pat yourself on the back, and reward yourself by eating a granola bar, a banana, and a handful of nuts.

Little do you know, though, you just ate even more calories than you burned, putting you back at square one.

Or, maybe your mistake isn’t entirely mindless. You come back from your run so hungry that you can’t help but scarf down a pint of Ben & Jerry’s.

The idea is that the calories you burn from exercise are always perpetually offset by an increase in hunger and a decrease in your ability to resist eating tasty food.

Is that true, though?

Science says, no.

The long story short is that the right kind and amount of exercise can make it easier to lose weight (and fat in particular), if you combine it with proper dieting principles.

The reason exercise has gotten such a bad rap isn’t because science has proven it’s worthless.

It’s because people are going about it the wrong way.

In this article, you’ll learn the 3 most common reasons people think exercise is useless for weight loss (and why they’re wrong) and how to use exercise to lose weight the right way.

Let’s start by debunking 3 popular myths surrounding exercise and weight loss.

The Top 3 Myths About Exercise and Weight Loss

There are 3 main reasons people say exercise doesn’t help you lose weight:

- Exercise just makes you overeat.

- Exercise only helps you lose weight by burning calories.

- Exercise doesn’t burn enough calories to make any difference in weight loss.

There’s a tiny grain of truth to all of these ideas, but at bottom, they’re more wrong than right.

Let’s start with number 1.

Exercise Weight Loss Myth #1

“Exercise just makes you overeat.”

We all know the story:

Exercise burns calories, which makes you hungry, which makes you eat too many calories, which equals one big waste of time and energy.

How true is that idea, though?

Is overeating after a workout a biological inevitability, or just a result of poor decisions?

Part of the answer comes to us from a study conducted by scientists at Loughborough University who wanted to see how exercise affected hunger and hunger-related hormones.

On separate occasions (spaced at least a week apart), researchers had everyone visit the lab and complete the following protocols:

- Run on the treadmill at an easy pace for about an hour.

- Run on the treadmill at a fast pace (breathing hard, but not flat-out) for about half an hour.

- Refrain from exercise (the control).

The researchers also made sure everyone burned the same number of calories during both workouts and had everyone track their food intake the day before each test, so that everyone was in the same size calorie deficit. (Except of course the control group, which didn’t exercise but did track their food intake).

Three hours after each protocol, everyone was provided with a meal based on their body size (bigger people ate more calories).

The researchers took several measurements right after the workout and at various intervals over the next few hours: they asked everyone to rate how hungry they felt after eating and took blood measurements of the hormone ghrelin, which tends to rise as people become more hungry.

If it’s true that exercise makes you overeat, then you’d expect that everyone who ran would feel significantly more hungry and have higher levels of ghrelin than the people who didn’t run.

What happened?

The runners were significantly less hungry and had lower ghrelin levels.

In other words, working out made them less likely to overeat.

Another test conducted by the same team decided to see if changing the duration of the workout might have a different effect.

They had another group of people run for 45 minutes or 90 minutes under the same conditions and took all of the same tests.

Once again, everyone felt less hungry and had lower ghrelin levels for hours after the workout.

It’s worth noting that some studies have shown that exercise increases ghrelin levels and food intake after a workout. On the whole, though, the majority of research shows that people don’t fully compensate for the calories they burn during a workout by overeating afterward.

In other words, they might eat slightly more throughout the day after a tough workout, but they still wind up burning more calories than they consume.

What’s going on here?

If you’re burning calories, it makes sense that your body would make you eat more to make up for the difference, right?

The missing piece of the puzzle seems to be that our hunger-controlling machinery seems to be more accurate when we maintain a higher overall energy expenditure.

The exact mechanisms are beyond the scope of this article, but the long story short is that exercise improves people’s ability to match their appetite to their true energy needs.

For example, let’s say that you normally burn 2,500 calories per day at your sedentary office job.

Over the past few months, you’ve been eating when you’re hungry and averaging about 3,000 calories per day, and it’s easy for you to eat 3,500+ calories per day without thinking about it.

If you were to raise your activity levels and burn 3,000 calories a day, though, it’s likely that your body would adjust its hunger-controlling machinery so that you’d be satisfied eating 3,000 calories per day.

And if you’re more satisfied after eating the same number of calories, it’s going to be easier to stick to a low-calorie diet.

This doesn’t work equally well for everyone, which is why some people eat significantly less after exercise and others eat more.

If you look at the majority of evidence, though, exercise seems to be a net positive when it comes to hunger control and weight loss.

To further back this up, many studies have shown that people who exercise at least 30 minutes per day have a significantly easier time maintaining their weight without tracking calories.

It’s not because burning those additional 200 to 300 calories per day let’s them eat whatever they want while staying lean.

It’s because exercise makes them feel more full on less food.

The fact remains, though, that there are plenty of people out there who are overweight and exercise constantly.

Does exercise just not work for them, or is there more to the story?

Let’s find out.

The Real Reason People Overeat After Exercise

In recent years, many people have claimed that willpower is a limited resource.

This leads the “exercise doesn’t work” crowd to claim that you should spend your limited willpower on restricting your calorie intake instead of working out.

It turns out, though, that this false dilemma might be part of the problem.

New research shows that if we choose to believe our capacity for willpower is unlimited, we can manage far more self discipline than if we believe our willpower is finite.

To illustrate this point, scientists at the University of Maastricht conducted a study in which they gave participants a challenge of controlling their facial expressions while viewing upsetting video clips.

One group of participants was told that the exercise would be energizing, while the other was told that it would be draining.

After viewing the videos, all participants squeezed a handgrip as hard as they could.

The result? The former group performed noticeably better.

Further proof that you can significantly change both your diet and exercise habits without running out of willpower comes from research conducted by scientists at Stanford University.

The researchers split 200 people into 3 groups that would be coached over the phone to:

- Eat healthier

- Exercise more

- Eat healthier and exercise more simultaneously

Everyone improved, but only the group that tried to eat healthier and exercise more at the same time was still maintaining their behaviors when the researchers called them again 12 months later.

So, why doesn’t it always work like this in real life? Why is it often so difficult for people to stick to a diet and exercise plan?

No one knows for sure, but here are 3 possible reasons:

- Many people who want to lose weight start exercising in combination with a highly restrictive, very low-calorie diet. It’s not necessarily the hour-long run that made people want to pillage the fridge afterward. It’s the fact that they were also eating 1,200 calories per day for the week prior.

- Nothing motivates people like results, and you’re going to get the best results if you eat properly and exercise more. Focusing on diet or exercise alone is always going to produce worse results and be less motivating than focusing on both.

- Other research suggests that if we look at exercise as a means to burn calories, then we’re more likely to look at it as a “license” to overeat later. If we look at exercise as something inherently enjoyable and beneficial, though, this isn’t the case.

These problems are compounded by the fact that people think they’re burning several hundred (or thousand) calories more than they really are during exercise, which makes it easier to rationalize overeating later.

For example, it’s not uncommon for people to claim they’re eating several hundred calories per day while burning several thousand calories from exercise without losing weight.

What happens if you actually measure their calorie intake and expenditure, though?

That’s what a team of scientists at Columbia University did in study on obese people who claimed to be eating less 1,200 calories per day without losing weight for 6 months.

When they measured everyone’s food intake, energy expenditure, and body composition under controlled, scientific conditions, they found two interesting results:

- Most people in the study were burning over 2,500 calories per day—without exercise—simply due to moving around such large bodies.

- They reported eating 1,000 to 1,600 calories per day, when in reality they were eating 2,000 to 2,300 calories per day.

- Most people thought they were burning 50% more calories from exercise than they really were.

- On a meal-to-meal basis, most people underestimated how much they ate by about 20%.

- The people who were the worst at estimating their energy expenditure and intake were also the most likely to struggle with losing weight.

The fact is that most people have no clue how many calories exercise actually burns. One popular example is the myth that Michael Phelps ate 12,000 calories per day to fuel his rigorous training regimen.

As he clarified later in his autobiography, that was a hoax his teammates created as a joke. His actual calorie intake was about what you’d expect for someone training 4 to 6 hours per day: around 5 to 6 thousand calories per day.

Sure, that’s a lot of food, but not anything close to what many people think.

At bottom, exercise doesn’t “make” people overeat by sapping their willpower or making them hungry.

The reason some people overeat after exercise is because they view it as a means to burn calories, and then overestimate how many calories they’ve burned and how many calories they can reward themselves with later.

In other words, it’s a choice, not an biological inevitability.

Recommended Reading:

Exercise Weight Loss Myth #2

“Exercise only helps you lose weight by burning calories.”

It’s often assumed that the only way exercise helps you lose weight is by burning calories.

As a result, people fixate on the kinds of exercise that they think burn the most calories or that allow them to measure how many calories they’re burning.

In other words, cardio.

So they put in the hours on the spin bike, elliptical, and stairmaster, restrict their calories, and sure enough—they lose weight.

They aren’t happy with the results, though.

Instead of getting the lean, muscular, defined look they wanted, they wound up “skinny fat,” like this:

These people shouldn’t be ashamed of their bodies, but these aren’t the physiques most people would want after years of hard work.

So, what did they get wrong?

If they’re like most people, they fell into the all-to-common trap of assuming that exercise is just a tool to burn more calories.

The truth is that exercise does something much more important—it improves your body composition.

Body composition represents how much of your body is composed of muscle, fat, minerals, and other compounds.

There are several models of determining body composition, but you can simplify it into 2 categories:

- Fat mass. This is simply all of the fat in your body.

- Fat-free mass (FFM). This is everything that isn’t fat: muscle, bone, blood, organs, water, glycogen, and the rest.

The single biggest mistake people make when trying to get in shape is conflating weight loss with fat loss.

Your goal isn’t necessarily to lose weight. It’s to reduce your fat mass and (depending on your goals) maintain or gain muscle mass.

Burning more calories can help us with the first part of this equation, but it does little in the way of preserving or building our muscle.

This is where exercise becomes an essential part of your weight loss plan.

Specifically, heavy, compound strength training.

It’s better than workout machines, “pump” classes, bodyweight exercises, Yoga, Pilates, and everything else you can do to improve your body composition.

What do I mean by “heavy compound” strength training, though?

By “heavy,” I mean that you should work primarily with weights in the range of 70 to 80% of your one-rep max (1RM) or 7 to 9 relative perceived exertion (RPE), which includes weights that you can do 6 to 10 reps with before failing.

And by “compound,” I mean that you should focus your efforts on exercises that train several major muscle groups, like the squat, deadlift, and bench press.

This kind of training is far superior for maintaining and gaining muscle mass than anything else you can do, which is the key role of exercise when losing weight.

Training this way doesn’t just help you build more muscle—it can also help you lose fat faster.

Although heavy strength training may not leave you in the same sweaty, heart-pounding, breathless mess as high-rep, low-weight workouts or cardio, it still burns about as many calories. This is mainly due to what’s known as the “afterburn effect,” which is the rise in metabolic rate that occurs between sets and after your workout as your body recovers.

To give you an idea of how this works, let’s review a study conducted by scientists at Ball State University that had two groups of women perform two different training protocols:

- One group did high-rep, low-weight, superset style training with minimal rest between sets.

- The other group followed a periodized strength training routine with most of the reps around 70 to 90% of their 1RM.

After 12 weeks, both groups lost about 20 pounds (meaning the workouts burned about the same number of calories), but the group that did heavy strength training gained 3 times more muscle (7 pounds versus 2 pounds) and lost over twice as much body fat.

Want to know what that looks like in the real world?

Here are a few people who’ve followed this “strength training first” approach to weight loss:

These people didn’t focus on exercise as a way to burn calories. Instead, they focused on exercise as a way to gain and preserve muscle while maintaining a calorie deficit (which we’ll cover in a moment).

This is why dismissing exercise as a means to lose weight is misguided.

Sure, cardio often doesn’t burn as many calories as people think. And yes, trying to lose weight by only burning more calories is often a recipe for failure.

That doesn’t mean that all forms of exercise are useless for weight loss. Throwing the baby out with the bathwater and all that.

If you use the right kind of exercise, not only will you lose weight faster, you’ll also improve your body composition, muscle definition, and whole-body strength, which is the key to building a body you can be proud of.

You’ll learn exactly how to use strength training and small amounts of cardio to get the body you want at the end of this article.

Recommended Reading:

Exercise Weight Loss Myth #3

“Exercise doesn’t burn enough calories to make any difference in weight loss.”

It’s true that exercise doesn’t burn as many calories as many believe.

In fact, our total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) is mostly comprised of these 3 factors:

1.Basal metabolic rate (BMR) which is the amount of energy we burn at rest.

This is the minimum amount of energy we need to expend to stay alive, and usually accounts for around 60 to 80% of our daily energy expenditure.

2. Daily non-exercise activity.

This includes all forms of movement that aren’t formal exercise.

Things like walking to the office, getting up to go to the bathroom, or even bouncing your legs can burn a surprising number of calories throughout the day.

3. Digesting food.

This is known as the thermic effect of food (TEF), and it accounts for about 10 to 15% of your TDEE.

Add those 3 things together, and you’re left with about 10% of your TDEE coming from formal exercise.

The idea is that because your diet accounts for 100% of your “calories in,” and exercise only accounts for such a small fraction of your “calories out,” that it isn’t important in the grand scheme of things.

You don’t need to burn that many more calories every day to significantly speed up weight loss, though.

A pound of body fat contains about 3,500 calories of energy. To lose a pound of body fat, then, you need to create a daily calorie deficit of around 3,500 calories per week (in reality it never works out this perfectly, but it’s a good rule of thumb).

For example, let’s say someone needs 3,000 calories per day to maintain their weight.

They’re currently eating 2,500 calories per day which gives them a weekly calorie deficit of about 3,500 calories. Sure enough, they’ve been losing about a pound per week. They decide to add an extra 30 minutes of exercise to their daily routine, burning an additional 300 calories per day.

Now we’re at a daily calorie deficit of 800 calories per day or 5,600 calories per week, which works out to around 1.6 pounds of weight loss per week.

Over the course of 2 months, just restricting calories would lead to around 8 pounds of fat loss, while restricting calories and doing a modicum of exercise would lead to around 13 pounds of fat loss.

Which results would you rather have?

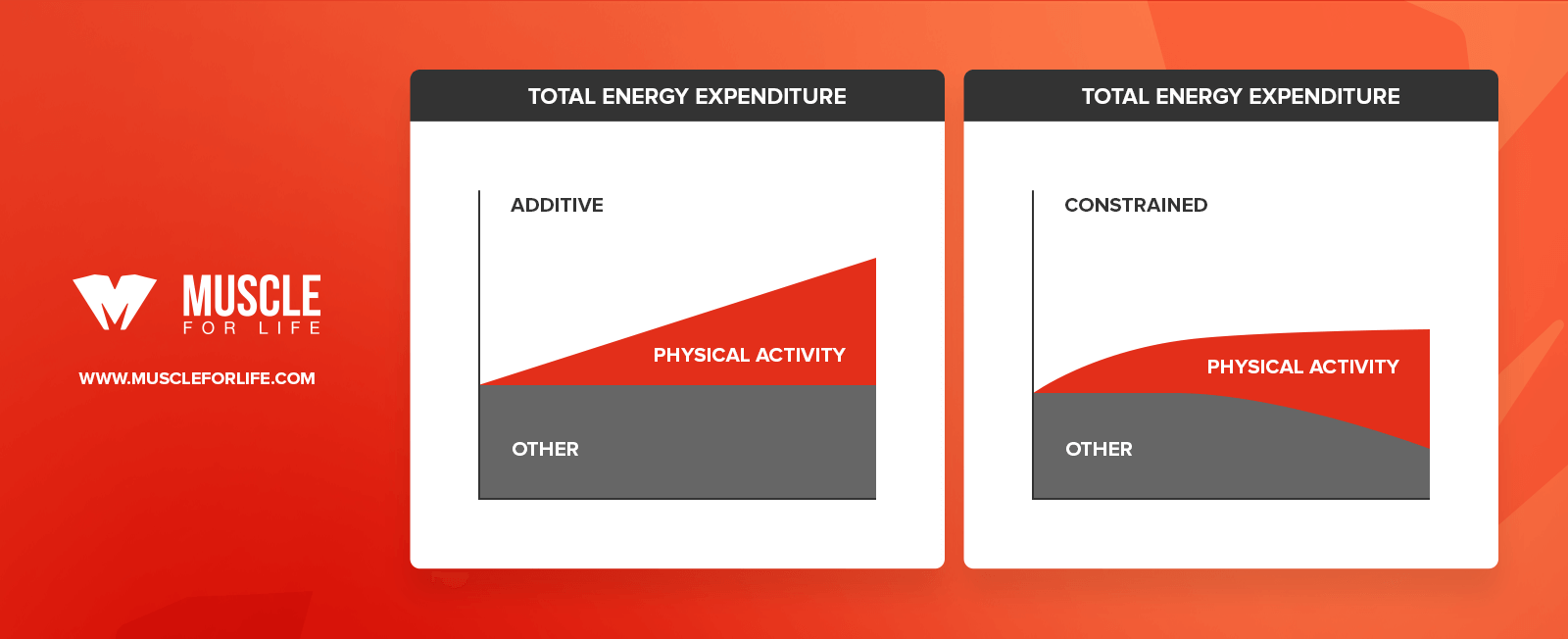

Now, something the exercise naysayers are quick to point out is that this “additive” model of energy balance isn’t entirely accurate.

Your body seems to have an internal limit on how many calories it wants to expend per day. It’s fine with burning slightly more calories than you burn, but if stray too far from this norm it deploys countermeasures to reduce your energy expenditure from other non-exercise activities.

That is, there’s a point of diminishing returns where burning more calories doesn’t translate into a proportional increase in your rate of weight loss.

This was demonstrated in a study conducted by scientists at City University of New York, which looked at how different levels of daily exercise affected people’s total daily energy expenditure in the real world.

The researchers had 332 people drink a substance known as “doubly-labeled water,” which allowed them to very accurately estimate how many calories these people were burning as they went about their daily routines.

They also had everyone wear an activity monitor to see how much they exercised every day.

Then, after 8 days, they looked at all of the data and determined how many calories everyone burned per day, and how many of those calories were burned through formal exercise versus other physical activity.

Here’s what it looked like when they graphed the numbers:

According to the traditional view of exercise, any additional physical activity you do on top of your normal activities should be “additive.” That is, the more you exercise, the more calories you burn.

What the researchers discovered, though, was that past a certain level of formal exercise, most people compensated by burning fewer calories throughout the rest of the day. In other words, their bodies “constrained” how many total calories they burned from all kinds of activity.

Does this mean exercise is useless for weight loss, though?

Not at all.

People who did a moderate amount of exercise still burned hundreds more calories per day than their sedentary peers.

In this case, a “moderate” amount of exercise worked out to about 30 to 60 minutes of exercise per day.

Here’s what this might look like in the real world.

Let’s say you’re already burning 600 calories per day from exercise.

You up your exercise levels so that you’re burning 900 calories per day, but you subconsciously offset some of those additional 300 calories burned by sitting more, fidgeting less, and taking the elevator instead of the stairs.

These little changes reduce your non-exercise calorie expenditure by around 100 calories per day, cutting your 900 calories burned to 800 calories burned.

Is that the most efficient way to burn calories?

No.

Does it mean exercise is useless, though?

No.

Even if you compensate by burning a little less energy throughout the rest of the day, if you’re still burning a few hundred calories more than you would otherwise, you’re going to lose weight faster. Period.

In the next section of this article, you’re going to learn exactly how much exercise you should do to lose weight, what kind of strength training plan you should follow to lose weight, and how to guarantee you get results by following proper dieting principles.

Recommended Reading:

The Right Way to Use Exercise to Lose Weight

Over the years, I’ve tried many different weight loss diets and training regimens.

Some have worked better than others, and over time, I’ve been able to glean enough workable principles and insights and then organize them into an extremely effective and efficient weight loss regimen.

With this regimen, you can lose about a pound of fat per week (more if you’re overweight, slightly less if you’re lean looking to get really lean) while preserving—or possibly even gaining—muscle.

Even better, you won’t have to struggle with hunger and cravings, your energy levels won’t crash, and you won’t have to do more than 6 to 8 hours of exercise per week (or about an hour a day).

In other words, you’ll get all of the benefits of exercise for weight loss with few or none of the downsides.

Here’s how you do it:

- Follow a meal plan.

- Do lots of heavy, compound strength training.

- Strategically use cardio to burn fat faster.

Let’s learn more about each.

1. Follow a meal plan.

Here’s one thing the exercise naysayers get right:

Regardless of how much or how intensely you exercise, it’s very easy to accidentally eat more calories than you expend.

The fact is that if you don’t put in the time to measure and manage your calorie intake, you’re always going to struggle to lose weight.

The absolute easiest way to fix this problem is to follow a meal plan.

There are many ways to meal plan, but here’s the one I’ve found most effective:

- Learn how many calories and grams of protein, carbohydrate, and fat (macronutrients) you need to eat every day to lose weight. (Don’t know how? Read this.)

- Create a single day’s worth of meals that meets your calorie and macro targets, and follow that plan every day.

- When you get tired of eating something in your plan—whether a simple snack or multifaceted meal like dinner—swap it for something else with the same amount of calories and macros.

This way you can have as much or little variety as you’d like (tip: reducing variety makes for an easier dieting experience), while also tightly regulating your food intake.

Don’t worry, either—this process isn’t difficult or time-consuming. You get to eat foods you actually like, so you don’t feel restricted, and it only takes 10 or 15 minutes.

If you want to learn how to build a meal plan that’s guaranteed to help you lose body fat, then you want to check out this article:

Once you have your diet taped, it’s time to focus on exercise for fat loss.

2. Do lots of heavy, compound strength training.

When it comes to losing fat, not weight, you can’t beat heavy, compounds strength training.

As we covered earlier, it …

- Helps preserve and build muscle.

- Increases energy expenditure.

- Increases your feeling of fullness after meals.

You can use any well-designed strength training program to accomplish these goals, but a good place to start is the push pull legs routine.

It trains every major muscle group in your body, allows plenty of time for recovery, and only takes 3 to 5 hours per week (depending on how many days you want to train).

Check out this article to learn how to set it up:

3. Strategically use cardio to burn fat faster.

The best way to include cardio in a weight loss regimen is to do as little as needed to reach your desired rate of weight loss and stay fit, and no more.

For best results do . . .

- At least two low- to moderate-intensity cardio workouts per week of 20-to-40 minutes each.

- One HIIT workout per week if you enjoy it.

- No more than 2-to-3 hours of cardio per week.

- Cardio and weightlifting on separate days. If that isn’t possible, lift weights first and try to separate the two workouts by at least 6 hours.

Although you’ll often hear fitness gurus tout HIIT as the most effective kind of cardio for fat loss, this isn’t true. Moderate-intensity, steady-state cardio is just as good at fat-burning, easier to recover from, and doesn’t sap your motivation or energy as much as HIIT, which is why I recommend you do it for the majority of your cardio workouts.

The Bottom Line on How to Use Exercise to Lose Weight

It’s become popular to say that exercise won’t help you lose weight.

The truth, though, is that exercise helps most people feel more full on less food, lose more fat instead of muscle, and can significantly speed up fat loss.

To get these benefits, though, you need to follow these 3 steps:

- Follow a meal plan

- Do lots of heavy, compound strength training

- Strategically use cardio to burn fat faster.

Do that, and you’ll lose fat, build or maintain muscle, and get the body you want faster than you would if you didn’t exercise.

P.S. Want to learn more about how to set up a strength training program for fat loss? Check out these articles to learn how:

→ The 12 Best Science-Based Strength Training Programs for Gaining Muscle and Strength

What’s your take on exercising helping with weight loss? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Tomiya, S., Kikuchi, N., & Nakazato, K. (2017). Moderate Intensity Cycling Exercise after Upper Extremity Resistance Training Interferes Response to Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength Gains. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 16(3), 391. /pmc/articles/PMC5592291/

- E R Helms, P J Fitschen, A A Aragon, J Cronin, & B J Schoenfeld. (n.d.). Recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: resistance and cardiovascular training - PubMed. Retrieved August 26, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998610/

- Alonso-Alonso, M., Woods, S. C., Pelchat, M., Grigson, P. S., Stice, E., Farooqi, S., Khoo, C. S., Mattes, R. D., & Beauchamp, G. K. (2015). Food reward system: current perspectives and future research needs. Nutrition Reviews, 73(5), 296. https://doi.org/10.1093/NUTRIT/NUV002

- DA, S. (2008). Insights into energy balance from doubly labeled water. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 32 Suppl 7, S72–S75. https://doi.org/10.1038/IJO.2008.241

- H, P., R, D.-A., LR, D., J, P.-R., P, B., TE, F., EV, L., RS, C., DA, S., & A, L. (2016). Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans. Current Biology : CB, 26(3), 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CUB.2015.12.046

- EJ, D., KA, K., JA, D., AS, A., KD, K., & DB, A. (2015). Predicting adult weight change in the real world: a systematic review and meta-analysis accounting for compensatory changes in energy intake or expenditure. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 39(8), 1181–1187. https://doi.org/10.1038/IJO.2014.184

- KR, W. (2013). Physical activity and physical activity induced energy expenditure in humans: measurement, determinants, and effects. Frontiers in Physiology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPHYS.2013.00090

- Westerterp, K. R. (2004). Diet induced thermogenesis. Nutrition & Metabolism 2004 1:1, 1(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-1-5

- Lam, Y. Y., & Ravussin, E. (2016). Analysis of energy metabolism in humans: A review of methodologies. Molecular Metabolism, 5(11), 1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MOLMET.2016.09.005

- JO, M., NA, R., BC, N., LA, G., JS, V., K, D., JA, B., AL, G., SA, M., SJ, F., K, H., RU, N., & WJ, K. (2001). Low-volume circuit versus high-volume periodized resistance training in women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(4), 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200104000-00019

- E, C., NC, Y., & B, M. (2017). Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss. Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 8(3), 511–519. https://doi.org/10.3945/AN.116.014506

- Duren, D. L., Sherwood, R. J., Czerwinski, S. A., Lee, M., Choh, A. C., Siervogel, R. M., & Chumlea, W. C. (2008). Body Composition Methods: Comparisons and Interpretation. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology (Online), 2(6), 1139. https://doi.org/10.1177/193229680800200623

- F, B., WH, S., J, S., E, B., R, T., NJ, R., & F, ten H. (1989). Eating, drinking, and cycling. A controlled Tour de France simulation study, Part I. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 10 Suppl 1(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2007-1024952

- SW, L., K, P., ER, B., M, P., H, D., E, O., H, W., S, H., DE, M., & SB, H. (1992). Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. The New England Journal of Medicine, 327(27), 1893–1898. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199212313272701

- ML, I., BE, A., & JM, C. (2001). Estimation of energy expenditure from physical activity measures: determinants of accuracy. Obesity Research, 9(9), 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/OBY.2001.68

- Werle, C. O. C., Wansink, B., & Payne, C. R. (2014). Is it fun or exercise? The framing of physical activity biases subsequent snacking. Marketing Letters 2014 26:4, 26(4), 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11002-014-9301-6

- King, A. C., Castro, C. M., Buman, M. P., Hekler, E. B., Urizar, G. G., Jr., & Ahn, D. K. (2013). Behavioral Impacts of Sequentially versus Simultaneously Delivered Dietary Plus Physical Activity Interventions: the CALM Trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 46(2), 157. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12160-013-9501-Y

- Martijn, C., Tenbült, P., Merckelbach, H., Dreezens, E., & De Vries, N. K. (2002). Getting a grip on ourselves: Challenging expectancies about loss of energy after self-control. Social Cognition, 20(6), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1521/SOCO.20.6.441.22978

- Swift, D. L., Johannsen, N. M., Lavie, C. J., Earnest, C. P., & Church, T. S. (2014). The Role of Exercise and Physical Activity in Weight Loss and Maintenance. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 56(4), 441. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PCAD.2013.09.012

- NA, K., K, H., AP, H., NM, B., RE, W., E, B., P, C., G, F., C, G., M, H., C, M., & JE, B. (2012). Exercise, appetite and weight management: understanding the compensatory responses in eating behaviour and how they contribute to variability in exercise-induced weight loss. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(5), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSM.2010.082495

- King, N. A., Hopkins, M., Caudwell, P., Stubbs, R. J., & Blundell, J. E. (2007). Individual variability following 12 weeks of supervised exercise: identification and characterization of compensation for exercise-induced weight loss. International Journal of Obesity 2008 32:1, 32(1), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803712

- C, M., L, M., & H, T. (2008). A review of the effects of exercise on appetite regulation: an obesity perspective. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 32(9), 1337–1347. https://doi.org/10.1038/IJO.2008.98

- NA, K., PP, C., M, H., JR, S., E, N., & JE, B. (2009). Dual-process action of exercise on appetite control: increase in orexigenic drive but improvement in meal-induced satiety. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(4), 921–927. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.2009.27706

- D, S. (2010). Exercise, appetite and appetite-regulating hormones: implications for food intake and weight control. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 57 Suppl 2(SUPPL. 2), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000322702

- Vatansever-Ozen, S., Tiryaki-Sonmez, G., Bugdayci, G., & Ozen, G. (2011). The Effects of Exercise on Food Intake and Hunger: Relationship with Acylated Ghrelin and Leptin. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 10(2), 283. /pmc/articles/PMC3761859/

- Church, T. S., Martin, C. K., Thompson, A. M., Earnest, C. P., Mikus, C. R., & Blair, S. N. (2009). Changes in Weight, Waist Circumference and Compensatory Responses with Different Doses of Exercise among Sedentary, Overweight Postmenopausal Women. PLoS ONE, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0004515

- Melanson, E. L., Keadle, S. K., Donnelly, J. E., Braun, B., & King, N. A. (2013). Resistance to exercise-induced weight loss: compensatory behavioral adaptations. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 45(8), 1600. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0B013E31828BA942

- Müller, T. D., Nogueiras, R., Andermann, M. L., Andrews, Z. B., Anker, S. D., Argente, J., Batterham, R. L., Benoit, S. C., Bowers, C. Y., Broglio, F., Casanueva, F. F., D’Alessio, D., Depoortere, I., Geliebter, A., Ghigo, E., Cole, P. A., Cowley, M., Cummings, D. E., Dagher, A., … Tschöp, M. H. (2015). Ghrelin. Molecular Metabolism, 4(6), 437. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MOLMET.2015.03.005

- DR, B., M, M., LK, W., R, P., JA, K., AE, T., & DJ, S. (2017). Acute effect of exercise intensity and duration on acylated ghrelin and hunger in men. The Journal of Endocrinology, 232(3), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-16-0561