Every day, more and more people are realizing the power of the barbell front squat.

It’s one of the all-time best lower-body exercises, it strengthens your core and back and improves your mobility, and it’s much easier to learn than it appears.

Many casual gymgoers avoid the front squat, though, because to them, it looks like a painfully awkward way to strangle yourself with a barbell.

That’s understandable.

The front squat does feel awkward and even a little painful at first, and you’re likely to question the wisdom of holding a heavy barbell against your gullet.

Learn proper front squat form, though, and you’ll soon find that the exercise isn’t nearly as dangerous or intimidating as it might seem.

Once you ingrain good front squat technique, the bar, arm, and wrist positions become comfortable and the movement becomes simple and smooth—and you’ll reap the benefits.

This article is going to help get you there.

Table of Contents

+

What Is a Front Squat?

The front squat is a lower-body exercise similar to the back squat.

What makes the front squat different from the back squat is where you position the bar. In the front squat, the bar lies across the front of your shoulders and is held in place against the base of your throat by your hands.

Shifting the weight from the back to the front of your body makes the exercise feel different and changes which muscles you emphasize.

Front Squat: Benefits

1. It trains several major muscle groups.

Most people think of the front squat as a leg exercise.

While it’s true that the front squat trains every major muscle group in your legs, research shows that it effectively trains several other major muscle groups across your entire body, including your glutes, back, shoulders, and abs.

2. It’s easier on your knees and back.

Research shows that the front squat places considerably less compressive forces on your knees and lower back than the back squat, which makes it a particularly good alternative to back squats for people who have knee or back issues.

3. It may improve athletic performance.

Studies show that people who have a strong front squat perform better in tests designed to measure athletic performance.

While this may be correlative rather than causative, there’s reason to believe that building a strong front squat will improve your performance in sports that require speed, agility, and power.

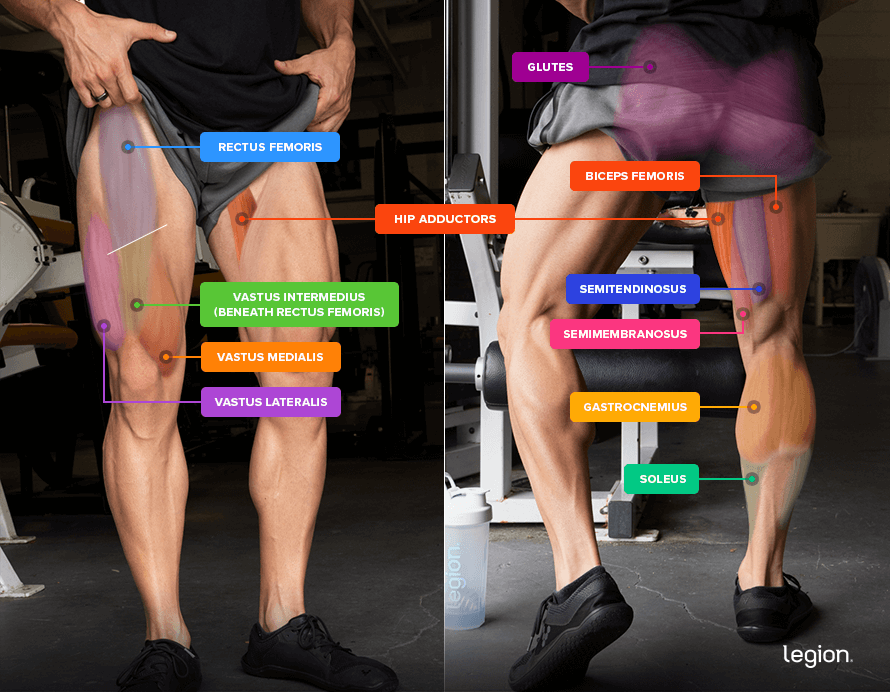

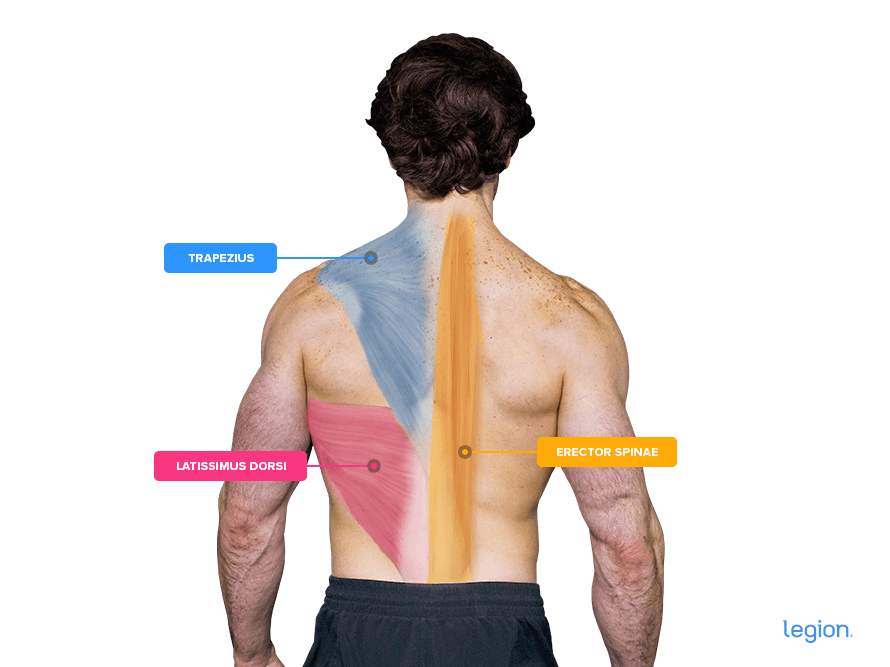

Front Squat: Muscles Worked

The front squat trains almost every major muscle group in your lower body, and many of the main muscle groups in your back.

Specifically, the muscles worked by the front squat include . . .

It also trains the shoulders and abs to a lesser degree, too.

Here’s how the main muscles worked by the front squat look on your body:

How to Front Squat with Proper Form

The best way to learn how to do a front squat is to split the exercise up into three parts: set up, descend, and squat.

Step 1: Set Up

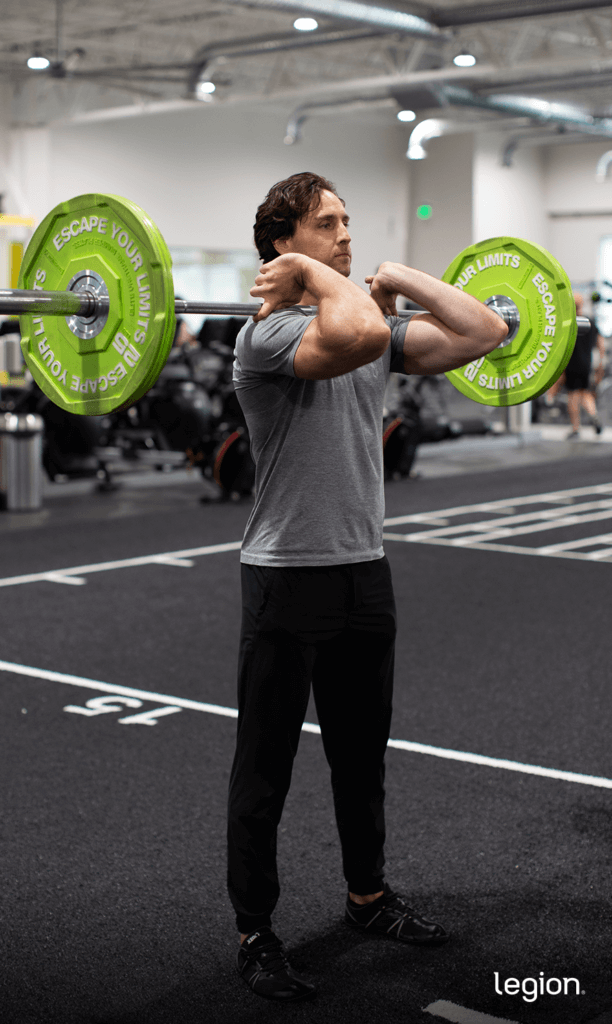

Position a barbell in a squat rack at about the height of your collarbone, like this:

Next, grip the bar.

There are numerous front squat grips you can use, but the two most common methods are wrapping all four fingers of each hand around the bar (full grip) and wrapping one, two, or three fingers around the bar (partial grip).

Most people don’t have the wrist mobility to take a full front squat grip, so I recommend you use a partial grip, like this:

This may seem unsafe, but when performed correctly, the bar’s weight rests on your shoulders, and your fingers just keep it from sliding forward.

To take a front squat grip (partial or full), first take hold of the bar while it’s in the rack with a shoulder-width grip and your palms facing away from you.

Step closer to the bar so that it presses against the front of your shoulders and push your elbows up and out in front of the bar.

For most people this will put the bar right at the base of the throat (it should almost feel like it’s choking you—almost).

Then lift the bar out of the rack, take one or two steps backward with both feet, and position your feet just outside of shoulder-width with your toes pointed slightly outward.

Here’s what you should look like:

Step 2: Descend

Take a deep breath into your belly, fix your gaze on a spot about 10 feet in front of you, and sit straight down. Remember to keep your back straight, elbows up, and push your knees out in the same direction as your toes.

The biggest mistake people make during the descent is letting their elbows drop. This causes the bar to slide forward on your shoulders, causing your upper back to round, and making it much more difficult to squat. A good cue to prevent this is to imagine trying to “touch the ceiling with your elbows.”

The second biggest mistake people make is letting their knees cave in toward one another. To avoid this, think about pushing the floor apart as you descend.

Keep descending until the crease of your hip (the point where your thigh meets your pelvis) is one-to-two inches below the tops of your knees.

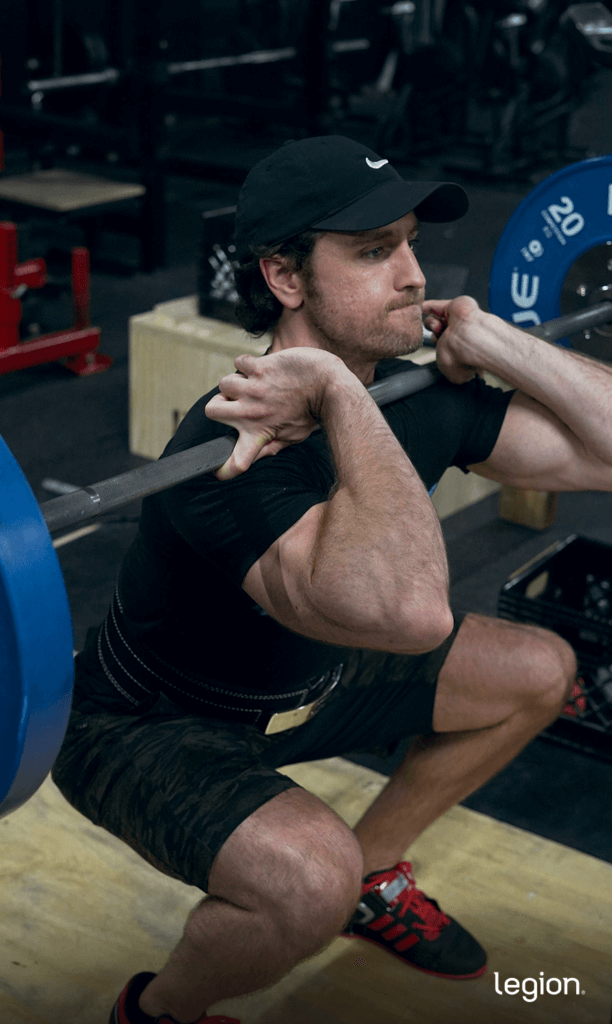

Here’s how you should look at the bottom of the front squat:

Step 3: Squat

Keeping your elbows up and back straight, stand up and return to the starting position. This is a mirror image of what you did during the descent.

The biggest mistake people make during this phase is relaxing one part of their body, like their upper back, core, or shoulders.

Thus, remember to keep everything tight during the ascent. Don’t relax your upper back, shoulders, or hands.

It’s also common for many people to let their upper back tilt forward as they begin to ascend, forcing them onto their tippy-toes and wasting energy. A good cue for countering this is to think about “pushing off your heels.” This helps keep the bar centered over your midfoot throughout the squat.

Here’s how it should look when you put all the pieces together:

The Best Front Squat Workout for Strength and Hypertrophy

Here’s an effective leg workout that prioritizes the front squat and also includes other exercises that train all of your lower-body muscles:

- Barbell Front Squat: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Romanian Deadlift: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Leg Press: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Hamstring Curl: 3 sets of 8-to-10 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

FAQ #1: Front squat vs. Back squat: Which is better?

Neither exercise is better or worse than the other. Although both exercises feel quite different, they train the same muscles to a similar degree, so you can use them interchangeably in your workouts.

One benefit of the front squat over the back squat, however, is that the front squat puts less pressure on your knees and lower back, which means it might be a better option than the back squat if you have knee or lower-back pain.

Of course, there’s no reason to choose just one. The best solution for most people is to include both exercises in your program.

A good way to do this is to include the back squat in your program for 8-to-10 weeks of training, take a deload, then replace the back squat with the front squat for the following 8-to-10 weeks of training.

Then, you can either continue alternating between the exercises every few months like this or stick with the one you prefer.

This is how I personally like to organize my training, and it’s similar to the method I advocate in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about how to schedule your workouts, how often you should train, and what exercises you should do to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

FAQ #2: What are the best front squat variations and front squat alternatives?

There are several front squat variations worth knowing:

- Dumbbell front squat

- Kettlebell front squat

- Zombie front squat

- Smith machine front squat

- Landmine front squat

The dumbbell front squat (sometimes referred to as the “DB front squat”) involves holding a dumbbell in each hand and resting one end of each dumbbell on your shoulders. Here’s what it looks like:

The dumbbell front squat works well if you don’t have a barbell (as during home workouts), but you’ll generally get more mileage out of the barbell variation.

The kettlebell front squat (or “double kettlebell front squat”) is exactly the same as the dumbbell front squat, except you hold a kettlebell in each hand instead of a dumbbell. Since the handles are oriented differently, the kettlebells will also lie across the backs of your forearms. Here’s what it looks like:

You can think of the dumbbell and kettlebell front squat as interchangeable—do whatever one you have equipment for.

The zombie front squat is a modified version of the front squat. Instead of using a regular front squat grip, you rest the bar across your shoulders and hold your arms straight out in front of your body (just like a zombie might walk in a movie). Here’s how it looks:

The main benefit of the zombie front squat is it teaches you to keep your back upright because if you don’t, the barbell will roll off your shoulders. It also works well for people who can’t perform the conventional front squat due to poor wrist or shoulder mobility.

Unfortunately, you can’t lift as much weight with the zombie front squat as you can with the front squat, making the exercise less effective for gaining muscle and strength.

The Smith machine front squat is the same as the regular front squat, only instead of using a barbell, you use a Smith machine. Here’s what it looks like:

The Smith machine front squat probably isn’t quite as effective at developing your lower-body muscles as the regular front squat, but it’s a workable front squat variation if you don’t have access to a barbell, you’re working around an injury, or you simply don’t want to do the barbell version.

Finally, the landmine front squat is a front-loaded squat alternative that involves placing one end of the barbell in a landmine attachment. This means the bar travels in a natural arc as you squat the weight up. Here’s how it looks:

The landmine front squat feels more comfortable and stable for some people than the regular front squat, which requires more wrist and shoulder mobility and full-body balance and coordination. However, the biggest drawback of the landmine front squat is it can be difficult to get the barbell into position once the weights get heavy.

FAQ #3: How do I keep my wrists from hurting while front squatting?

Two ways:

- Practice

- Use a partial grip

First, most people find that the awkward front squat hand position becomes much more comfortable after their first four or five workouts. This isn’t because the tendons are “lengthening” or the nerves as “deadending” or any other such piffle—you’re just getting used to a new and unfamiliar sensation.

The same thing is true if you find it painful to rest the barbell on your shoulders. While this is uncomfortable at first, you quickly get used to it.

Second, I highly recommend you use a partial grip instead of a full grip if you experience wrist pain or discomfort. This takes much of the stress off your wrists, makes it easier to maintain proper technique throughout every rep, and is just as secure as a full grip.

If after weeks of trying you still feel uncomfortable using a full or partial grip, you can switch to a “front squat cross grip” like this:

Many people find the cross-arm front squat variation more comfortable, but it’s also less stable, and thus limits how much weight you can lift.

Scientific References +

- Yavuz, H. U., Erdağ, D., Amca, A. M., & Aritan, S. (2015). Kinematic and EMG activities during front and back squat variations in maximum loads. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(10), 1058–1066. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.984240

- Krause Neto, W., Soares, E. G., Vieira, T. L., Aguiar, R., Chola, T. A., Sampaio, V. de L., & Gama, E. F. (2020). Gluteus Maximus Activation during Common Strength and Hypertrophy Exercises: A Systematic Review. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 19(1), 195. /pmc/articles/PMC7039033/

- Bautista, D., Durke, D., Cotter, J. A., Escobar, K. A., & Schick, E. E. (2020). A Comparison of Muscle Activation Among the Front Squat, Overhead Squat, Back Extension and Plank. International Journal of Exercise Science, 13(1), 714. /pmc/articles/PMC7241624/

- Gullett, J. C., Tillman, M. D., Gutierrez, G. M., & Chow, J. W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(1), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E31818546BB

- Peeni, M. H. (n.d.). The Effects of the Front Squat and Back Squat on Vertical Jump The Effects of the Front Squat and Back Squat on Vertical Jump and Lower Body Power Index of Division 1 Male Volleyball Players and Lower Body Power Index of Division 1 Male Volleyball Players BYU ScholarsArchive Citation BYU ScholarsArchive Citation. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd

- Hori, N., Newton, R. U., Andrews, W. A., Kawamori, N., Mcguigan, M. R., & Nosaka, K. (2008). Does performance of hang power clean differentiate performance of jumping, sprinting, and changing of direction? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(2), 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318166052B

- Bird, S. P., & Casey, S. (2012). Exploring the front squat. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34(2), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0B013E3182441B7D

- Schwanbeck, S., Chilibeck, P. D., & Binsted, G. (2009). A comparison of free weight squat to Smith machine squat using electromyography. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(9), 2588–2591. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181B1B181