When most people think of glute exercises, they think of barbell squats, deadlifts, and hip thrusts.

And while there’s no denying that these are great exercises for developing your derriere, they also require a level of skill, coordination, and strength that can be daunting if you’re new to weightlifting.

If you fall into this camp, the glute bridge is a better place to start.

That’s because the glute bridge is easier to learn, allows you to start with your body weight and progress slowly, and can be performed anywhere without the need for gym equipment.

Just because it’s more beginner-friendly doesn’t mean you can get away with using slipshod technique, though. Like any exercise, if you want to make the glute bridge as safe and effective as possible, you have to learn proper glute bridge form.

In this article, you’ll learn everything you need to know about how to do a glute bridge, including what a glute bridge is, the main glute bridge benefits, which muscles are worked by the glute bridge, the best glute bridge variations, and more.

What Is a Glute Bridge?

The glute bridge, also known as the “hip bridge” or the “butt bridge,” is a lower-body exercise that primarily trains the glutes.

There are several variations of the glute bridge that involve using equipment like the barbell glute bridge, dumbbell glute bridge, and banded glute bridge, but the most common (and the one we’ll focus on in this article) is the bodyweight glute bridge.

Glute Bridge vs. Hip Thrust

Many people think the glute bridge and the hip thrust are interchangeable.

While these two exercises are alike in that they both involve extending your hips (increasing the distance between your thighs and belly), there are some important differences.

The hip thrust is performed using a bench and a barbell, which means it’s easy to progressively overload, but you need access to a gym or well-stocked home gym if you want to perform it correctly.

The glute bridge, on the other hand, is a bodyweight exercise that requires no equipment and very little space. This makes it a better option for people who are new to weightlifting and don’t have the strength to add external resistance, are training around an injury, or are working out in a hotel or home gym and don’t have much space or equipment available.

Glute Bridge: Benefits

1. It effectively trains your glutes.

Most people have weak glutes because they spend too much time sitting on them rather than using them.

And when your glutes are weak, you rely more heavily on other muscles near to the glutes to help you move, which changes how your lower-body muscles function and could lead to pains, strains, and injuries.

(Although you’ll often hear people say that sitting is particularly bad for your glutes, it’s really inactivity on the whole that’s to blame for these ailments.)

What’s more, having weak glutes compromises your performance on exercises where your glutes are highly involved, like the squat and deadlift, and any sport that requires hip extension, including running, jumping, climbing, throwing, sidestepping, and landing.

Thus, strengthening your glutes helps you avoid many common aches and pains (particularly knee and lower-back pain) and perform better in almost every sport.

The glute bridge effectively trains and strengthens the glutes, which helps keep you pain- and injury-free and performing at your best.

(Oh, and it might make you more attractive, too.)

2. It’s easy to learn.

When it comes to glute exercises, most people think of proven glute builders like the back and front squat, Romanian deadlift, and hip thrust.

And while it’s true that these are among the best exercises for developing your glutes, they’re not always a great place to start if you’re new to weightlifting. That’s because people who are new to strength training often don’t have the requisite level of strength and skill to perform these exercises safely and effectively.

The glute bridge trains the glutes and hamstrings in a similar way to the barbell exercises above, but it’s easier to learn and allows you to start with just your body weight and build strength over time. This makes it ideal for people who are just getting started with weightlifting and/or don’t want to go to a gym (yet!).

3. It’s highly adaptable.

There are many bodyweight glute bridge and weighted glute bridge variations you can do, including the . . .

- Single-leg glute bridge

- Banded glute bridge

- Dumbbell glute bridge

- Barbell glute bridge

- Smith machine glute bridge

. . . so no matter how you like to train or what equipment you have available, you can almost always find an effective glute bridge variation to include in your workouts.

More about how to do these variations soon!

Glute Bridge: Muscles Worked

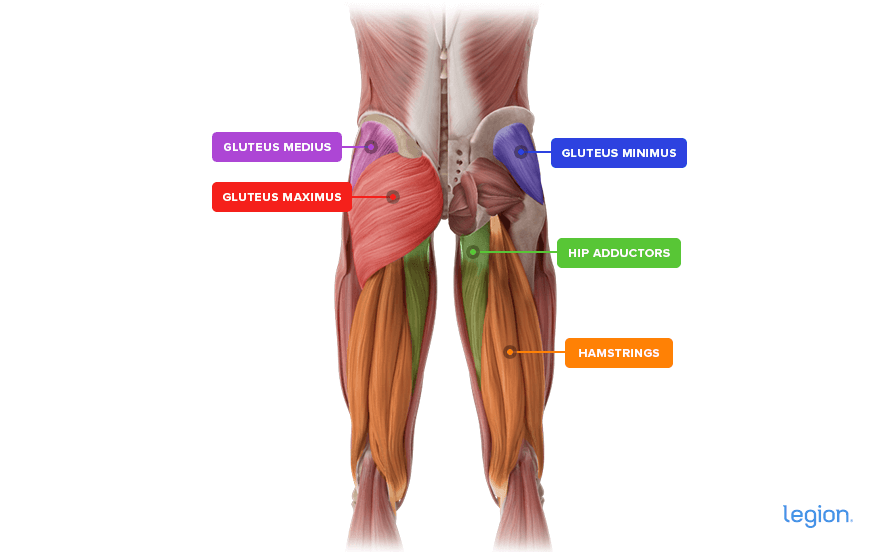

The main muscles worked in the glute bridge are the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus, the hamstrings, and the hip adductors.

Here’s how those muscles look on your body:

How to Do the Glute Bridge

The best way to learn how to do a glute bridge is to break the exercise up into three parts: set up, thrust, and descend.

Step 1: Set Up

Lie on your back on the floor with your arms by your sides and your palms facing toward the floor, then place your feet 15-to-18 inches apart about 6-to-12 inches from your butt and point your toes slightly outward (research shows placing your feet like this makes the exercise more effective at training your glutes).

Step 2: Thrust

Lift your butt off the floor by pressing your shoulders and heels into the floor. As you thrust your hips toward the ceiling, push your knees out in the same direction as your toes. Continue thrusting your hips upward until your butt, hips, and knees form a straight line and your shins are vertical.

Step 3: Descend

Reverse the movement and return to the starting position. This is a mirror image of what you did during the thrust. Lower your body under control, and once your glutes touch the floor, begin the next rep.

The Best Glute Bridge Variations

1. Single-Leg Glute Bridge

The single-leg glute bridge, also known as the “one-leg glute bridge,” “one-legged glute bridge,” or “SL glute bridge,” is a more advanced version of the regular glute bridge that requires you to lift your entire body weight using just one leg at a time. This makes the single-leg glute bridge useful for identifying and evening out any size or strength imbalances you might have.

Tip: Research shows that you can increase the amount of work your glutes have to do in the single-leg glute bridge by bringing your heel closer to your butt while performing the exercises (6-to-8 inches works well for most people).

2. Barbell Glute Bridge

The barbell glute bridge is an excellent glute bridge variation because it allows you to safely and effectively increase the weight you lift over time, which is one of the best ways to maximize the muscle-building effects of weightlifting.

3. Banded Glute Bridge

The banded glute bridge is a good alternative to the bodyweight glute bridge when you want to make the exercise harder, but don’t have access to a gym (when traveling, for example). To set up the glute bridge with band, sit on the floor and lay a resistance band across your lap and pin each end of the band to the floor on either side of your body using something heavy (like weight plates or dumbbells). Then, lie back and perform the exercise the same way you would perform the regular glute bridge.

4. KAS Glute Bridge

The KAS glute bridge looks similar to the hip thrust, but it’s performed with a much shorter range of motion. Although some people prefer this because it allows them to “isolate” the glutes, most studies show that longer ranges of motion are better for muscle growth, which means you’re probably better off with the barbell glute bridge or hip thrust. That said, the KAS glute bridge is a viable alternative to the barbell glute bridge if you’re looking for ways to change up your routine.

5. Static Glute Bridge Abduction

The static glute bridge abduction is a more advanced variation of the bodyweight glute bridge that involves wrapping a resistance band around your thighs and performing “hip abduction” (moving your thighs outward, away from the midline of your body), which increases the amount of work your glutes have to do.

To perform static glute bridge abduction, wrap a resistance band in a loop around your thighs, then get set up as you would for the bodyweight glute bridge. Thrust your hips toward the ceiling until your butt, hips, and knees form a straight line. This is the starting position. To perform a rep, squeeze your glutes and push your thighs outward against the resistance of the band, then allow your thighs to move back toward each other and return to the starting position.

6. Glute Bridge March

The glute bridge march (or “marching glute bridge”) is a bodyweight glute bridge variation that allows you to train each side of your body independently, which means it’s good for identifying and evening out any muscle imbalances you might have. Unlike most other glute bridge variations, however, the glute bridge march requires ample balance and coordination, which means it might not be suitable if you’re very new to strength training.

7. Elevated Glute Bridge

The elevated glute bridge involves performing a glute bridge with your feet elevated one-to-two feet off the floor on a stable box or bench. This makes it more difficult than the regular glute bridge, which means it’s a good variation to use once the regular glute bridge becomes too easy.

8. Dumbbell Glute Bridge

The dumbbell glute bridge (or “db glute bridge”) is the same as the barbell glute bridge, only instead of using a barbell you use a dumbbell. Doing the glute bridge with a dumbbell is a good option if you’re working out in a hotel or home gym and don’t have a barbell available, or if you’re new to weightlifting and want to start out with a weight that’s lighter than a barbell.

9. Glute Bridge Hold

The glute bridge hold involves getting into position to perform a regular glute bridge, thrusting your hips toward the ceiling until your butt, hips, and knees form a straight line and your shins are vertical, holding this position for 5-to-10 seconds, then lowering your butt to the ground and repeating.

Performing the glute bridge with an “isometric” hold at the top of each rep increases the time your glutes are “under tension,” which makes it more challenging than the regular glute bridge and may increase its muscle-building effects. That said, the glute bridge hold likely isn’t as effective as performing weighted glute bridge variations, so you should only use it when you’re just starting out or have no equipment available.

10 . Smith Machine Glute Bridge

The Smith machine glute bridge probably isn’t quite as effective at developing your glutes as other weighted glute bridge variations, but it’s a workable alternative if you don’t have access to a barbell, dumbbell, resistance band, or glute bridge machine. It can also be a viable option if you’re training around an injury or you simply don’t want to do the barbell version.

The Best Glute Bridge Workouts

If you want to maximize muscle growth, research shows that it’s best to train your muscles in different ways, from different directions, and at different angles.

Thus, a proper “glute bridge workout” should also include other exercises that train your glutes and other lower body muscles, such as your quads, hamstrings, and calves.

Here are two example glute bridge workouts: one that requires a barbell and one that uses just your body weight.

The Best Weighted Glute Bridge Workout

- Barbell Back Squat: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Barbell Glute Bridge: 3 sets of 8-to-10 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Romanian Deadlift: 3 sets of 8-to-10 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Single-Leg Glute Bridge: 3 sets of 10-to-20 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

The Best Bodyweight Glute Bridge Workout

- Bodyweight Bulgarian Split Squat: 3 sets of 10-to-20 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Single-Leg Glute Bridge: 3 sets of 10-to-20 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Bodyweight Squat: 3 sets of 10-to-20 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

- Elevated Glute Bridge: 3 sets of 10-to-20 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

And if you want more workouts like these, as well as a diet plan that’ll help you build muscle, lose fat, and get healthy, check out my best-selling fitness books Bigger Leaner Stronger for men, and Thinner Leaner Stronger for women.

Scientific References +

- Achalandabaso-Ochoa, A., Aibar-Almazán, A., Martínez-Amat, A., Pecos-Martín, D., Vidal-Aragón, G., Calderón-Corrales, P., Acuña, Á., & Gallego-Izquierdo, T. (2020). Effects of a Gluteal Muscles Specific Exercise Program on the Vertical Jump. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH17155383

- Presswood, L., Cronin, J., Keogh, J. W. L., & Whatman, C. (2008). Gluteus medius: Applied anatomy, dysfunction, assessment, and progressive strengthening. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 30(5), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0B013E318187F19A

- Wagner, T., Behnia, N., Ancheta, W. K. L., Shen, R., Farrokhi, S., & Powers, C. M. (2010). Strengthening and neuromuscular reeducation of the gluteus maximus in a triathlete with exercise-associated cramping of the hamstrings. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 40(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.2519/JOSPT.2010.3110

- Barbalho, M., Coswig, V., Souza, D., Serrão, J. C., Hebling Campos, M., & Gentil, P. (2020). Back Squat vsHip Thrust Resistance-training Programs in Well-trained Women. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(5), 306–310. https://doi.org/10.1055/A-1082-1126/ID/R7619-0030

- Lee, S., Schultz, J., Timgren, J., Staelgraeve, K., Miller, M., & Liu, Y. (2018). An electromyographic and kinetic comparison of conventional and Romanian deadlifts. Journal of Exercise Science and Fitness, 16(3), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JESF.2018.08.001

- Behrens, M. J., & Simonson, S. R. (2011). A comparison of the various methods used to enhance sprint speed. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 33(2), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0B013E318210174D

- Achalandabaso-Ochoa, A., Aibar-Almazán, A., Martínez-Amat, A., Pecos-Martín, D., Vidal-Aragón, G., Calderón-Corrales, P., Acuña, Á., & Gallego-Izquierdo, T. (2020). Effects of a Gluteal Muscles Specific Exercise Program on the Vertical Jump. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH17155383

- Bartlett, J. L., Sumner, B., Ellis, R. G., & Kram, R. (2014). Activity and functions of the human gluteal muscles in walking, running, sprinting, and climbing. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 153(1), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/AJPA.22419

- Plummer, H. A., & Oliver, G. D. (2014). The relationship between gluteal muscle activation and throwing kinematics in baseball and softball catchers. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318295D80F

- Houck, J. (2003). Muscle activation patterns of selected lower extremity muscles during stepping and cutting tasks. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology : Official Journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology, 13(6), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1050-6411(03)00056-7

- Struminger, A. H., Lewek, M. D., Goto, S., Hibberd, E., & Blackburn, J. T. (2013). Comparison of gluteal and hamstring activation during five commonly used plyometric exercises. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 28(7), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CLINBIOMECH.2013.06.010

- Khayambashi, K., Ghoddosi, N., Straub, R. K., & Powers, C. M. (2016). Hip Muscle Strength Predicts Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Male and Female Athletes: A Prospective Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(2), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546515616237

- Added, M. A. N., Freitas, D. G. de, Kasawara, K. T., Martin, R. L., & Fukuda, T. Y. (2018). STRENGTHENING THE GLUTEUS MAXIMUS IN SUBJECTS WITH SACROILIAC DYSFUNCTION. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 13(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.26603/ijspt20180114

- Singh, D. (n.d.). Ideal female body shape: role of body weight and waist-to-hip ratio - PubMed. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7833962/

- Kang, S. Y., Choung, S. D., & Jeon, H. S. (2016). Modifying the hip abduction angle during bridging exercise can facilitate gluteus maximus activity. Manual Therapy, 22, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MATH.2015.12.010

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- Bloomquist, K., Langberg, H., Karlsen, S., Madsgaard, S., Boesen, M., & Raastad, T. (2013). Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(8), 2133–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-013-2642-7

- Kubo, K., Ikebukuro, T., & Yata, H. (2019). Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(9), 1933–1942. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-019-04181-Y

- McMahon, G. E., Morse, C. I., Burden, A., Winwood, K., & Onambélé, G. L. (2014). Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318297143A

- Schwanbeck, S., Chilibeck, P. D., & Binsted, G. (2009). A comparison of free weight squat to Smith machine squat using electromyography. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(9), 2588–2591. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181B1B181

- Barakat, C., Barroso, R., Alvarez, M., Rauch, J., Miller, N., Bou-Sliman, A., & De Souza, E. O. (2019). The Effects of Varying Glenohumeral Joint Angle on Acute Volume Load, Muscle Activation, Swelling, and Echo-Intensity on the Biceps Brachii in Resistance-Trained Individuals. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 7(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/SPORTS7090204