There’s a reason why most people are turned off by “healthy eating.”

Namely, it sucks.

Depending on whom you listen to, you’re likely to hear things like…

- No grains

- No dairy

- No meat

- No eggs

- No sugar

- No snack foods

And if your response is “no thanks”…I understand.

Many people’s idea of “eating healthy” can be quite expensive as well.

Some “gurus” would have you believe that anything less than a (high-priced) 100% organic diet is going to turn your insides into a cancerous swamp.

Unfortunately, all this nonsense is denying people the immense benefits and enjoyment that can come from a truly healthy, well-balanced diet.

Benefits like weight loss, muscle growth, mood enhancement, better sleep, better energy levels, and much, much more.

And, just to make myself clear, by “healthy, well-balanced diet,” I mean one that includes all the foods you actually like, including wheat, dairy, sugar, and red meat.

That’s what this article is going to be all about: the real science of healthy eating, and why it’s not just for ascetics and people with eating disorders.

So, let’s start with the worst “healthy eating” myth out there:

That you have to “eat clean to get lean.”

The Truth About Healthy Eating and Weight Loss

The cult of “clean eating” is more popular than ever these days.

I’m all for eating nutritious (“clean”) foods for the purposes of supplying our bodies with essential vitamins and minerals, but eating nothing but these foods guarantees nothing in the way of weight loss.

The truth is you can be the cleanest eater in the world and still be weak and skinny fat.

Why?

Because, when it comes to body composition (how much muscle and body fat you have), how much you eat is more important than what.

Claiming that one food is “better” than another for losing or gaining weight misses the forest for the trees.

Foods don’t have any special properties that make them better or worse for weight loss or weight gain.

What they do have, however, are varying amounts of potential energy as measured in calories, and various macronutrient breakdowns.

These two factors are what make certain foods more conducive to weight loss or gain than others.

Generally speaking, foods that are “good” for weight loss are those that are relatively low in calories but high in volume (and thus satiating).

Examples of such foods are lean meats, whole grains, many fruits and vegetables, and low-fat dairy.

These types of foods also provide an abundance of micronutrients, which is especially important when you’re dieting to lose weight.

Foods conducive to weight gain are the opposite: high in calories and lower in volume and satiety.

These foods include the obvious like caloric beverages, snack foods, fast food, candy, and other sugar-laden goodies, but quite a few “healthy” foods fall into this category as well, such as:

- Oils

- Bacon

- Butter

- Low-fiber fruits

- Whole fat dairy products

- Fatty meats

- Avocado

Don’t think that means you can’t lose weight eating foods more suitable to gaining weight and vice versa, though.

A rather extreme example of the former is a simple experiment carried out by Professor Mark Haub from Kansas University.

Mr. Haub lost 27 pounds in 2 months on a diet of protein shakes, Twinkies, Doritos, Oreos, and Little Debbie snacks, and you could do exactly the same if you wanted to (not that you should though, and I’ll explain more on this soon).

Think of it this way:

You can only “afford” so many calories every day, whether dieting to lose fat or gain muscle, and you have to watch how you “spend” them.

When you want to lose weight, you want to spend the majority of your calories on foods that allow you to hit your daily calorie and macronutrient targets without struggling with hunger and cravings.

When you want to gain weight, however, you have quite a few more calories to spend every day. And that means you can “afford” to eat a much wider variety of foods.

That said, I’m not a fan of the hordes of “IIFYMers” that are on a quest to get shredded eating as much processed junk food as possible.

Remember that our bodies need more than just protein, carbs, and fat to function properly.

They also need myriad vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients that we can only get from relatively unprocessed foods like fruits and vegetables.

Here’s a good rule of thumb:

If you get the majority (~80%) of your calories from relatively unprocessed, nutrient-dense foods, you can fill the remaining 20% with your favorite dietary sins and be healthy, muscular, and lean.

How to Create a Healthy Eating Plan

Now that we’ve addressed the most important and controversial aspect of healthy eating (weight loss), let’s take a step back and look at dieting as a whole and how to create meal plans that give us the healthy, lean, and muscular body that we want.

Every year, a rash of new weight loss diets and theories hits the bookstores, magazine stands, blogs, and airwaves, and they all have one thing in common:

The assertion that theirs is the One True Way.

The Paleo hordes say you should eat like your ancient cave-dwelling ancestors. The anti-carbers demand you sacrifice yourself to ketogenic dieting. The quacks swear by “cleanses” and “detoxes” and “biohacking” and other nonsense.

You can fool away months and years this way, defecting from one ideology to another with little to show for it.

Well, the “secret they’re not telling you” about dieting is it’s rather boring, really. It doesn’t have a sexy hook or powerful “unique selling proposition.”

It does have this, though:

The truth is simple. And workable. For everyone. Every time.

Thomas Edison once said that “opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.”

Dieting is like that.

Suckers are drawn to the lure of shiny shortcuts and magic powders and potions, but the real opportunity lies along the road less traveled.

And that road is well worn but long and narrow. It requires patience and vigilance, but it also guarantees you’ll arrive at your destination.

So, here’s where it begins:

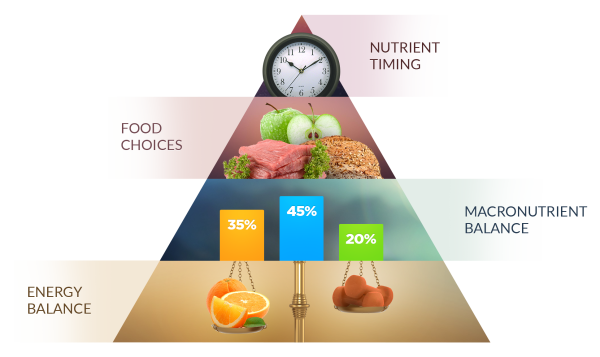

Let’s look at each of the layers in detail.

Energy Balance

Energy balance is at the bottom because it’s the overarching principle of dieting.

This is the one that dictates your weight gain and loss more than anything else, which in turn dictates much of your health.

Energy balance is simply the relationship between the energy you feed your body and the energy it expends.

Yes, I’m talking about calories in vs. calories out, but don’t worry–we’re going to go beyond that.

For now, though, here’s what you need to understand:

- Meaningful weight loss requires you to burn more energy than you eat.

- Meaningful weight gain requires the opposite: burn less energy than you eat.

If you’re shaking your head, thinking I’m drinking decade-old Kool-Aid, answer me this:

Why has every single controlled weight loss study conducted in the last 100 years…including countless meta-analyses and systematic reviews…concluded that energy balance alone dictates weight loss and gain?

Why have bodybuilders been using this knowledge for over a century now to systematically reduce and increase body fat levels as desired?

And why does every new brand of “calorie denying” that pops up on bookshelves fail to gain acceptance in the weight loss literature?

The bottom line is this:

A century of metabolic research has proven, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that energy in vs. energy out is the basic mechanism that regulates fat loss and gain.

There are extenuating circumstances that cause the body to respond abnormally to caloric deficits and surpluses (mainly medical issues and medications), but in the vast majority of people, energy balance alone tells you everything you need to know about why they can’t lose or gain weight.

Now, at this point, you’re probably wondering how many calories you should be eating based on your body and goals.

Check out this article to find out.

Macronutrient Balance

I promised we’d go deeper than “a calorie is a calorie,” and this is the first layer.

Macronutrients are any of the nutritional components of the diet that are required in relatively large amounts, such as protein, carbohydrate, fat, and minerals such as calcium, zinc, iron, magnesium, and phosphorous.

When we’re talking diet, however, “macros” usually refers to just protein, carbs, and fat.

Macros are important because we don’t want to just gain and lose weight.

We want to optimize our body composition, and when that’s the goal, how we balance our macros matters nearly as much as how many calories we eat.

The macronutrient that matters most is protein.

Your carbs and fat can be all over the place without completely derailing you, but eating too little protein is the cardinal sin of dieting for us health and fitness folk.

This is because protein most determines how well you gain and preserve muscle, which most determines how your body looks and, in many ways, how it feels and functions as well.

Simply put: the more muscle you have, the better.

Read this article to learn more about how to properly set up your macros for gaining muscle and losing fat.

Food Choices

As you now know, your food choices have little impact on your body composition.

You can lose weight and gain muscle eating junk food so long as your calories and macros are set up properly.

That’s why food choices are given short shrift by many “flexible dieters” and other people that understand the fundamentals of energy and macronutrient balance.

Well, just because you can eat a nutritionally bankrupt diet and be lean and muscular doesn’t mean you should.

You see, there’s a reason why people that eat higher amounts of fruits and vegetables are, on the whole, healthier and more likely to live longer, disease-free lives than those who don’t eat enough.

One of the reasons eating enough fruits and vegetables is so beneficial is the essential vitamins and minerals they provide.

However, another lesser-known reason is they can also contain other types of phytonutrients that confer a variety of health benefits.

Two good examples of this are sulforaphane and anthocyanins, which are found mainly in broccoli and blueberries, respectively.

They are known to have a variety of beneficial health effects but are not found on food labels, which focus only on essential nutrients vital to life.

“Nonvital” phytonutrients like these, however, are one of the major reasons why a multivitamin can’t completely replace a vegetable-rich diet.

This is why healthy eating includes a wide variety of plants and vegetables, ranging from dark, leafy greens to onions and garlic to cruciferous vegetables and more.

Now, it can be argued that being lean and muscular and exercising regularly negates many of the deleterious effects of a nutritionally weak diet, but why use that as an excuse to eat poorly when you can have the best of both worlds?

That is, why not reap the immense benefits from both “healthy dieting” and exercise?

This is why I recommended earlier that you get at least 80% of your daily calories from nutritious foods and, if you’d like, fill the rest with “goodies.”

For example, I get the majority of my calories from foods like these:

- Avocados

- Greens (chard, collard greens, kale, mustard greens, spinach)

- Bell peppers

- Brussels sprouts

- Mushrooms

- Baked potatoes

- Sweet potatoes

- Banana & berries

- Low-fat yogurt

- Eggs

- Seeds (flax, pumpkin, sesame, and sunflower)

- Beans (green, black, garbanzo, kidney, navy, pinto)

- Almonds, pecans, cashews, peanuts

- Barley, oats, quinoa, brown rice

- Halibut, cod, tilapia, sea bass, tuna

- Lean beef, lamb, venison

- Chicken, turkey

And if I’m in the mood for something sweet, chocolate, ice cream, cookies, and/or muffins are my go-tos.

Nutrient Timing

Generally speaking, when you eat your food doesn’t matter.

So long as you’re managing your energy and macronutrient balances properly and getting the majority of your calories from nutritious foods, meal timing and frequency aren’t going to help your hinder your results.

You can eat three or seven meals per day. You can eat a huge breakfast or skip it and start eating at lunch. You can eat carbs whenever you like.

That said, if you’re serious about weightlifting, there are a few caveats:

- There’s a fair amount of evidence that eating protein before and after weightlifting workouts can help you build muscle and strength over longer periods of time.

- There’s also evidence that post-workout carbohydrate intake, and high-carbohydrate intake in general, can help as well, mainly due to insulin’s anti-catabolic effects.

So, if you’re lifting weights regularly, I do recommend you have 30 to 40 grams of protein before and after your workouts.

30 to 50 grams of carbohydrate before a workout is great for boosting performance and 1 gram per kilogram of bodyweight is enough for post-workout needs.

How to Eat Healthy on a Budget

You don’t have to blow through half your paycheck every week to eat healthy.

In fact, eating junk food can be more expensive in the short term and is certainly more expensive in the long term when you consider the costs of poor health.

So, in this section of the article, I want to share with you a variety of simple ways eat healthy foods without breaking the bank.

How to Eat High-Quality Protein on a Budget

Here are my favorite healthy, inexpensive sources of protein:

Eggs

Eggs one of the best all-around sources of protein, with about 6 grams per egg, and are also a great source of healthy fats.

They also have several health benefits such as reducing the risk of thrombosis, and raising blood concentrations of two powerful antioxidants, lutein and zeaxanthin.

Some people avoid eggs to avoid the cholesterol they contain, but both epidemiological and clinical research has shown it doesn’t increase the risk of heart disease.

With an average price of about $1.60 per dozen, eggs offer a lot of nutrition at a great price.

Chicken Breast

There’s a reason why us fitness folk eat so much chicken: it’s cheap, extremely high in protein, and low in fat and thus calories.

One of the downsides to chicken is it’s much higher in omega-6 fatty acids than omega-3s (contributing to the imbalance prevalent in Western diets), but this can be addressed by supplementing with a good fish oil or regularly eating fatty fish like salmon, tuna, trout, herring, sardines, or mackerel.

A pound of chicken breast has about 100 grams of protein and will cost you about $3.50.

Packaged/Canned Salmon

There are many types of salmon that you can buy, ranging from Atlantic to Chinook to chum, from coho to pink to sockeye, and each variety can be a rather different experience.

Furthermore, the texture and fullness of flavor vary based on whether the fish was wild caught or farm raised, and fresh salmon is quite different from the packaged variety.

Though “wild caught” sounds like the healthier alternative, the science is ambiguous.

In terms of nutritional profiles, few significant differences exist between wild-caught and farm-raised fish.

Wild-caught trout, for example, have more calcium and iron than their farm-raised counterparts, which offer more vitamin A and selenium. Farmed and wild-caught rainbow trout, however, are nearly identical in terms of nutrients.

In many cases, farm-raised fish offer significantly more of those all-important omega-3 fatty acids mentioned earlier.

Farmed Atlantic salmon, for instance, provide more omega-3s than wild-caught Atlantic salmon.

The presence of contaminants in wild-caught versus farm-raised fish is also less of a concern than many have made it out to be.

A 2004 study made waves when it reported that levels of potentially carcinogenic chemicals (PCBs) in farmed fish were ten times higher than in their wild-caught brethren.

What the headlines didn’t say, though, is the amount of PCBs present was still less than 2% of the amount considered dangerous.

Further studies have found similar levels of contaminants in farm-raised and wild-caught fish.

The issue of environmental impact of farmed and wild-caught fish is also murky, as both involve unsustainable practices.

The Seafood Watch program sponsored by the Monterey Bay Aquarium is one of the best sources of information on the specific concerns impacting different types of fish.

Salmon contains about 22 grams of protein and 12 grams of fat per 4-ounce serving, and costs about $7 per pound.

It also has remarkably low levels of mercury, which means you can eat it as frequently as you’d like without risking your health.

Low-Fat Cottage Cheese

You can buy a ½-cup serving of low-fat cottage cheese for less than a dollar, and you get 14 grams of protein and only 1 gram of fat.

I think it tastes great with just a dash of salt and pepper, but also like it with fruit like pineapple or berries.

And if you like to get creative in the kitchen, check out these killer cottage cheese recipes.

Protein Powder

Protein powder is generally thought of as a “luxury supplement,” but it can be a cost-efficient source of protein.

For example, if you head over to www.truenutrition.com and build a 100% whey isolate with natural chocolate flavoring and stevia sweetener, it will cost you about $12 per pound.

How to Eat High-Quality Carbs on a Budget

Regular intake of nutritious carbs is associated with a reduced risk of chronic disease.

Here are some of my favorite choices:

Oatmeal

Like cottage cheese, oatmeal can be enjoyed simply or can be transformed into a variety of meals.

One cup of dry steel cut oats packs just over 50 grams of carbs, 10 grams of protein, and 6 grams of fat.

You can buy oats in bulk for about $1 per pound, and it’s a great source of soluble fiber, which is one of the reasons research shows it can reduce levels of LDL (“bad”) cholesterol.

Beans

Beans are a fantastic source of carbs as well as potassium, calcium, folic acid, and fiber.

Boil them up and they make a great side to any protein dish, and they also make terrific soups, dips, and other culinary delights.

One cup of beans contains about 40 grams of carbs, 15 grams of protein, and 1 gram of fat, and you can buy them for about $1 to 1.50 per pound.

Rice

Rice is the source of more than 1/5th of all calories consumed by humans, and accordingly is one of the world’s most important crops.

It’s dirt cheap—about $2 per pound—and one cup provides close to 45 grams of carbs, 5 grams of protein, and 2 grams of fat.

While there’s nothing wrong with white rice per se, brown rice is lower on the glycemic index and contains nearly four times the fiber as white rice, and contains more vitamins, minerals, and other beneficial micronutrients as well.

This helps explain why research has shown that whole grains like brown rice can reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes whereas refined grains like white rice can increase it. In the end, though, the difference are small.

White Potato

Potatoes are often vilified as “unhealthy,” but this is nonsense.

One potato serving provides 6.6 grams of dietary fiber and more than 20% of your RDA of vitamin C, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and manganese.

Furthermore, potatoes contain a number of compounds that improve heart health.

In addition to being high in potassium, which several studies have associated with a reduced risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, potatoes are also great sources of chlorogenic acid and kukoamines, both of which can help prevent high blood pressure.

Potatoes are also great for weight loss because they are highly filling.

A study on how filling various foods are identified potatoes as the most satiating out of a list of 40 common foods.

Thus, it’s no surprise that further research has found that eating potatoes during a meal can reduce overall calorie consumption compared to pasta or white rice.

And the best part? The price.

Potatoes cost about $0.60 per pound, which yields close to 95 grams of carbs, 10 grams of protein, and less than 1 gram of fat.

Quinoa

Most people think quinoa is a grain, but it’s actually a seed.

And it might be hard to pronounce (keen-wah), but it’s tasty, cheap (about $3 to 4 per pound), and highly nutritious.

One cup of cooked quinoa contains 40 grams of carb, 8 grams of protein, 5 grams of fiber, 58% of your daily manganese requirements, 30% of your magnesium RDA, 28% of your phosphorus needs, and more than 10% of your daily RDA of folate, copper, iron, zinc, potassium, and vitamins B1, B2, and B6.

It’s even got small amounts of calcium, niacin, vitamin E, and omega-3 fatty acids, too.

Seeds are also naturally free of gluten, making quinoa a good choice for people with celiac disease or gluten intolerance.

Sweet Potato

Prepare sweet potatoes correctly and they can be almost indulgent, and they’re also full of vitamin A, B, and other micronutrients.

One cup of mashed sweet potato provides you with about 60 grams of carbs, 4 grams of protein, and less than 1 gram of fat.

At a paltry cost of about $1 per pound, you can’t afford to leave the sweet potato out of your diet.

Fruit

You really can’t go wrong with fruit.

My favorite choices are strawberry, grapes, apples, banana, and orange, which are full of a variety of antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, and (in some cases) fiber.

All range between $0.60 and $1.50 per pound as well, so it’s easy to work into your budget.

The Bottom Line on Healthy Eating

Healthy eating doesn’t have to be an ordeal.

You don’t have to hew to dogmatic diets or constantly choose between what “should” and “want” to eat.

All you really have to do is two things:

- Regulate your caloric and macronutrient intake according to your goals.

- Eat many more nutritious foods than non-nutritious ones.

And if you really want to be a shining paragon of health, exercise regularly as well.

Yes, these are “restrictions” in that you probably can’t live off of gas station food and be healthy, but they’re not asking much of you, either.

If you ask me, as far as dieting goes, it’s as good as it gets.

What’s your take on healthy eating? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- J, E., Y, H., F, L., S, W., & V, S. (2007). Food intake and plasma ghrelin response during potato-, rice- and pasta-rich test meals. European Journal of Nutrition, 46(4), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00394-007-0649-8

- S H Holt, J C Miller, P Petocz, & E Farmakalidis. (n.d.). A satiety index of common foods - PubMed. Retrieved July 6, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7498104/

- IJ, O., EA, S., MJ, T., & CJ, H. (2015). The effect of chlorogenic acid on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Human Hypertension, 29(2), 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/JHH.2014.46

- PK, W., & J, H. (2014). Health effects of sodium and potassium in humans. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 25(1), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0000000000000033

- Q, S., D, S., RM, van D., MD, H., VS, M., WC, W., & FB, H. (2010). White rice, brown rice, and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(11), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHINTERNMED.2010.109

- TM, W., SM, T., AL, G., J, B.-M., AM, D., V, H., B, L., BA, T., R, D., & PJ, W. (2010). Physicochemical properties of oat β-glucan influence its ability to reduce serum LDL cholesterol in humans: a randomized clinical trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(4), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.2010.29174

- AW, B., P, P., J, M.-P., VM, F., T, P., P, M., & JC, B.-M. (2008). Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk--a meta-analysis of observational studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(3), 627–637. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/87.3.627

- Hites, R. A., Foran, J. A., Carpenter, D. O., Hamilton, M. C., Knuth, B. A., & Schwager, S. J. (2004). Global Assessment of Organic Contaminants in Farmed Salmon. Science, 303(5655), 226–229. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1091447

- AP, S. (2002). The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie, 56(8), 365–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00253-6

- Mutungi, G., Ratliff, J., Puglisi, M., Torres-Gonzalez, M., Vaishnav, U., Leite, J. O., Quann, E., Volek, J. S., & Fernandez, M. L. (2008). Dietary Cholesterol from Eggs Increases Plasma HDL Cholesterol in Overweight Men Consuming a Carbohydrate-Restricted Diet. The Journal of Nutrition, 138(2), 272–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/138.2.272

- FB, H., MJ, S., EB, R., JE, M., A, A., GA, C., BA, R., D, S., FE, S., FM, S., CH, H., & WC, W. (1999). A prospective study of egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women. JAMA, 281(15), 1387–1394. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.281.15.1387

- EF, G., TA, W., SC, H., R, V., PA, S., G, H., & RJ, N. (2006). Consumption of one egg per day increases serum lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations in older adults without altering serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(10), 2519–2524. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/136.10.2519

- HJ, C., HS, H., DS, L., & HJ, P. (2003). Effects of proteins from hen egg yolk on human platelet aggregation and blood coagulation. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 26(10), 1388–1392. https://doi.org/10.1248/BPB.26.1388

- L, F., TE, M., S, K., & JO, H. (2007). Long-term low-calorie low-protein vegan diet and endurance exercise are associated with low cardiometabolic risk. Rejuvenation Research, 10(2), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1089/REJ.2006.0529

- Wang, X., Ouyang, Y., Liu, J., Zhu, M., Zhao, G., Bao, W., & Hu, F. B. (2014). Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ, 349. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.G4490

- RR, W. (2006). The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 84(3), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/84.3.475

- GA, H., RP, S., AE, P., M, B., EP, C., JR, J., VK, P., TG, H., JR, H., DP, O., E, A., S, B., & SN, B. (2013). The energy balance study: the design and baseline results for a longitudinal study of energy balance. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 84(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.816224

- SC, W. (1972). Physiologic versus cognitive factors in short term food regulation in the obese and nonobese. Psychosomatic Medicine, 34(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197201000-00007