Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of barbell squat: the high-bar and the low-bar squat.

These names have nothing to do with the equipment you’re using—both involve a standard barbell—but instead refer to where you hold the barbell on your back while squatting.

To wit, the high-bar squat has the bar 2 to 3 inches higher on your shoulders than the low-bar squat.

Although this is a subtle change, it’s enough to modify the mechanics of the exercise so that they feel like very different exercises. This, in turn, has led many people to wonder which kind of squatting is better for gaining muscle and strength.

The long story short is that both styles of squatting have pros and cons for different people and goals, but neither is necessarily “better” or “worse” for everyone.

In this article, you’ll learn what the high-bar and low-bar squats are, how to do them with proper form, and when you should use one versus the other.

Table of Contents

+

The High-Bar vs. Low-Bar Squat

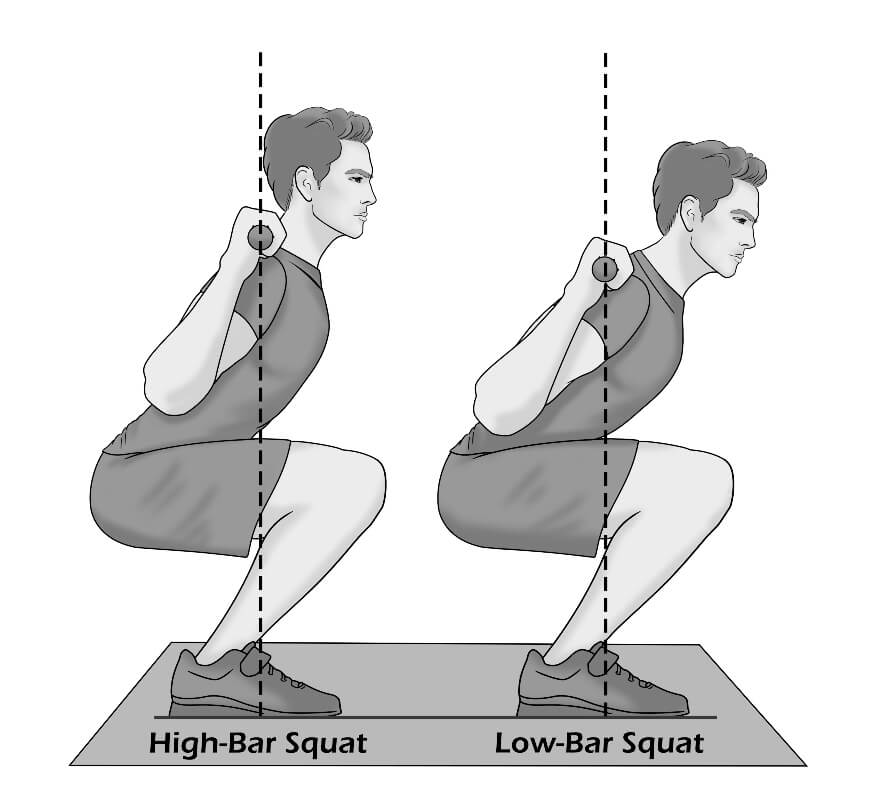

The high-bar squat has the bar resting directly on the upper trapezius muscles, whereas low-bar squat has the bar resting between the upper traps and rear deltoids (about 2 to 3 inches lower down your back).

Here’s what this difference looks like:

The primary difference you’ll notice while squatting, aside from where the bar presses into your back, is that your torso remains more upright and your knees travel farther forward in the high-bar squat than in the low-bar squat.

Here’s what this looks like:

You may also be wondering, why not place the bar somewhere between these two points? A medium-bar position?

The reason for this is that your back has two anatomical “notches” where you can securely position a barbell: one on top of your traps (the high-bar position) and one on top of your rear deltoids and shoulder blades (the low-bar position). Aside from these two points, there are no other secure places to hold the barbell on your back.

You can try and put the bar somewhere between the high- and low-bar positions, but you’ll probably find that it just slides down to the low-bar position after a few reps.

Anyway, some people claim that this difference in torso angle between the high-bar and low-bar squat drastically changes the muscles that are trained by each variation. Specifically, what you’ll typically hear is that the high-bar squat preferentially trains your quads, whereas the low-bar squat emphasizes your lower-back and glute muscles.

You’ll also notice that you can probably squat 5 to 10% more weight using the low-bar position instead of the high-bar position. This has led many people to think that the low-bar squat is better for gaining muscle because it allows you to use heavier weights.

And almost all of this is twattle.

First, let’s address the faulty idea that high-bar squats are better at training your quads and low-bar squats are better at training your glutes and lower-back. Evidence against this idea comes from a study published by scientists in the Journal of Human Kinetics, which found that muscle activation of the quads, glutes, hamstrings, and spinal erectors was identical in well-trained weightlifters using both the high-bar and low-bar squat positions.

That is, both squat variations trained all of the relevant muscle groups equally.

Other research has found similar results when comparing muscle activation during the front and back squat and when using full (“ass-to-grass”) and parallel squats.

Basically, so long as you’re squatting with heavy weights relatively close to failure and using proper squat technique, all squat variations train your quads, glutes, hamstrings, and lower-back muscles about equally.

So, if muscle activation is the same during the high- and low-bar squat, why can most people lift more weight in the low-bar position?

This is because the low-bar squat position puts you in a slightly more mechanically advantageous position for squatting heavy loads than the high-bar squat position. Although your muscles produce the same amount of force during both styles of squatting, the low-bar position is a little more efficient at using that force to move the barbell.

Think of it this way: Although two cars might produce the same horsepower (force), the one with better gearing will be able to pull heavier loads. So it is with the squat—you can think of the low-bar squat as having slightly better “gearing” for moving the barbell.

The important thing to remember, though, is that the absolute amount of weight on the bar isn’t what makes your muscles grow. Instead, it’s the amount of tension you force your muscles to produce, and research shows that the high- and low-bar squats both produce about the same amount of tension in your muscle fibers (technically, activation, which is a decent proxy).

Thus, both kinds of squatting (and front squats, for that matter), are all roughly equal in terms of their ability to build muscle.

This isn’t to say that everyone can benefit from both styles of squatting equally, though.

Should You High-Bar or Low-Bar Squat?

If you’re like me, and you have fairly average limb lengths, mobility, looks, intelligence . . . *begins sobbing quietly* . . . and you just want to get stronger, build muscle, and stay healthy, then it doesn’t matter what style of squatting you do. You can stick entirely to high- or low-bar squatting or do a combination of both—do whatever suits your druthers.

That said, if you’re a bit of an anatomical anomaly or you have more specific goals, then you may want to be strategic about which kind of squat you choose.

You may prefer the low-bar squat position if . . .

- You have long femurs. In this case, the low-bar squat position will likely make it more comfortable for you to reach parallel (the point at which your thigh is parallel to the floor).

- You want to lift as much weight as possible or compete in powerlifting. In most cases, people can lift about 5 to 10% more in the low-bar position, which makes it a better choice for most powerlifters.

- You have poor ankle, knee, or hip mobility, which can make high-bar squatting uncomfortable.

- You’re bored with high-bar squatting and want to try something new.

And you may prefer the high-bar squat position if . . .

- You have limited shoulder or wrist mobility. This can make it difficult to get your hands in the proper position during the low-bar squat.

- Your lower-back hurts when low-bar squatting. The low-bar squat requires a more aggressive forward lean, making the high-bar squat more comfortable for some people. That said, both styles of squatting still place a lot of stress on your back, so you may want to try front squatting instead, which places even less stress on your back (or, you know, take some time of squatting to let your back heal).

- You’re bored with low-bar squatting and want to try something new.

Some people also report that they don’t feel as “tight” or secure while high-bar squatting, but this is mostly just a matter of practice. After a few weeks of high-bar squatting this should no longer be an issue.

Personally, I like to use both variations in my workouts. If I’m squatting once per week, I’ll usually focus on either the high-bar or the low-bar position for at least 12 to 16 weeks before switching to the other style. If I’m squatting twice per week, I’ll often squat high-bar one day and low-bar the other day.

In the main, it doesn’t matter whether you use a high or low-bar squat position. Both are equally effective for building muscle and strength, and the only reason to use one over the other is due to anatomical differences, personal preference, or to compete in powerlifting.

There’s one rider to the above point that has to do with working programming: Whatever style of squatting you choose, make sure you do it at least once per week for at least 8 to 12 weeks, preferably longer. The reason for this is that constantly switching back and forth between high and low bar squats every week makes it difficult to master either style, which reduces how much weight you can use and thus how much muscle you build.

And if you really can’t decide which style you want to try first, start with the low-bar position. It’ll let you use slightly heavier weights, so why not give it a whirl first?

Scientific References +

- E R Helms, P J Fitschen, A A Aragon, J Cronin, & B J Schoenfeld. (n.d.). Recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: resistance and cardiovascular training - PubMed. Retrieved July 15, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998610/

- PD, C., AW, C., DG, S., & CE, W. (1998). A comparison of strength and muscle mass increases during resistance training in young women. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 77(1–2), 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/S004210050316

- B, C., AD, V., BJ, S., C, B., & J, C. (2016). A Comparison of Gluteus Maximus, Biceps Femoris, and Vastus Lateralis Electromyography Amplitude in the Parallel, Full, and Front Squat Variations in Resistance-Trained Females. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 32(1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1123/JAB.2015-0113

- JC, G., MD, T., GM, G., & JW, C. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(1), 284–292. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E31818546BB

- Tillaar, R. van den, & Helms, E. (2020). Comparison of Muscle Activation and Kinematics in 6-RM Squatting with Low and High Barbell Placement. Journal of Human Kinetics, 74(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.2478/HUKIN-2020-0021