Key Takeaways

- Powerlifting is a sport that consists of lifting as much weight as possible on the squat, bench press, and deadlift for a single repetition (of each exercise).

- Although many people think powerlifting only helps you gain strength, it’s also an outstanding way to build muscle if you follow an effective powerlifting routine.

- Keep reading to learn how powerlifting competitions work, how to train for powerlifting, and to get a free powerlifting training plan!

Powerlifting has become more and more popular in the past few decades, and you’ve probably heard many different things about this sport.

Let’s start with the obvious stuff.

When most people think of powerlifting, they think of someone like Eddie Hall, one of the strongest men in the world:

In other words, most people associate powerlifting with being big and strong, but not very lean or “aesthetic.” (Granted, Hall is a strongman, not a powerlifter, but this observation still holds true).

There’s even an old joke in the fitness world that goes, “If you can’t get lean enough for bodybuilding, you can always try powerlifting.”

Many people who are new to powerlifting also fear getting injured.

For example, they see videos like this . . .

And assume that powerlifting is about as good for your health as making out with a table saw.

Finally, there’s the less common but still prevalent idea that most powerlifters are just fit guys and gals with freakishly good genetics for pushing and pulling heavy things, and if you don’t have these Kryptonian DNA then there’s not much point in giving powerlifting a go.

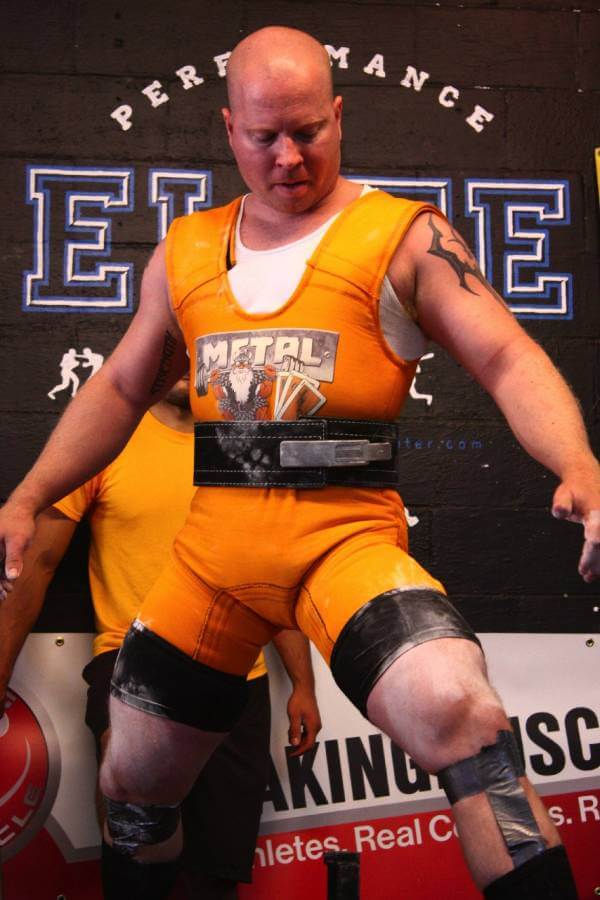

For example, if you saw this guy on the street you probably wouldn’t assume he could squat in the mid 500s, deadlift over 600, and bench over 300 pounds . . .

. . . but he can:

So, if you have a lot of conflicting emotions about whether or not you should try powerlifting, I understand.

Once you take a closer look at what powerlifting really is, though, you’ll quickly realize the truth:

- It’s not about getting as big and strong as possible regardless of how much fat you gain.

- It’s not dangerous compared to most sports when done properly.

- It’s not reserved for the freakishly strong genetic elite.

In fact, the reality of powerlifting is that . . .

- It’s one of the single best ways to gain muscle and strength

- It’s an outstanding sport for both beginner and advanced lifters, and everyone in between.

- It’s one of the healthiest and safest ways to stay in shape, assuming you follow a well-designed program and use proper technique.

The bottom line is that if you’re new to lifting weights or an old hand who’s interested in getting as strong as possible, you want to learn about powerlifting.

Let’s start by defining exactly what this sport is.

What Is Powerlifting?

Powerlifting is a sport that consists of lifting as much weight as possible on the squat, bench press, and deadlift for a single repetition (rep).

That is, you work up to the heaviest possible weight you can for a single rep of the squat, then the bench press, then the deadlift.

You perform all three of these exercises at a powerlifting “meet,” where you take turns with other lifters to see who can lift the most weight on these exercises.

Here’s how a powerlifting meet works:

- All of the competitors are divided into different weight classes based on their body weight the day before or of the meet (depending on the rules of that particular competition) and their sex.

The cutoffs for different weight classes vary depending on what powerlifting federation is in charge of the competition you take part in, but in general they work in ~20-pound increments for men and ~10-pound increments for women.

For example, here are the weight class cutoffs for USA Powerlifting and the International Powerlifting Federation:

| Men | Women |

| <117 pounds | <95 pounds |

| <130 pounds | <104 pounds |

| <146 pounds | <126 pounds |

| <163 pounds | <139 pounds |

| <183 pounds | <159 pounds |

| <205 pounds | <185 pounds |

| <231 pounds | >185 pounds |

| <265 pounds | |

| >265 pounds |

You always compete in the weight class above your actual weight on the day of or before the competition (depending on what the organizers decide). For instance, I’m a 180-pound guy, so I would complete in the 183-pound weight class. If I were 185-pounds, I’d compete in the 205-pound weight class, because I’d be too heavy to compete in the 183-pound weight class.

- Each lifter gets three attempts to lift as much weight as possible on the squat, bench press, and deadlift, for a total of nine attempts (three per exercise).

- In a pre-arranged order, everyone in a particular weight class makes their first attempt at the squat. Once everyone is finished with their first attempt, they make their second attempt in the same order, and so on and so forth until everyone has made three attempts at the squat.

- Next, the process is repeated for the bench press, and then finally for the deadlift.

- Most lifters start with a weight that’s slightly lower than their goal for the day and attempt to build up to a new best one-rep max by their third attempt.

For example, if I was gunning for a new squat PR of 455 pounds, my attempts might look something like this :

Squat Attempt #1: 405 pounds

Squat Attempt #2: 435 pounds

Squat Attempt #3: 455 pounds

- Three judges observe each lift, and they each judge whether or not the competitor completed the lift with proper technique. If a judge believes the lifter did complete the lift with proper technique, they turn on a white light. If a judge believes the lifter didn’t complete the lift with proper technique, they turn on a red light.

- If a competitor gets two or more white lights, the lift counts toward their score. If someone gets two or more red lights, the lift doesn’t count toward their score.

- At the end of the meet, the best single rep of each competitor’s squat, bench press, and deadlift is added together, which represents their powerlifting total—or their best squat, bench press, and deadlift combined.

- The person with the highest total in each weight class wins.

For example, let’s say you went to a powerlifting meet and achieved the following:

Squat

First Attempt: 355 pounds

Second Attempt: 375 pounds

Third Attempt: 400 pounds

Bench Press

First Attempt: 250 pounds

Second Attempt: 275 pounds

Third Attempt: 300 pounds

Deadlift:

First Attempt: 425 pounds

Second Attempt: 450 pounds

Third Attempt: 475 pounds

Remember, you only add up the best attempt for each exercise, so in this case you would add up the following:

Squat: 400 pounds

Bench Press: 300 pounds

Deadlift: 475 pounds

Here’s what the math looks like:

400 + 300 + 475 = 1,175 pounds

Thus, your total for this meet would be 1,175 pounds.

Now, let’s say you got two red lights on your third attempt of the deadlift. In this case, your third attempt of 475 pounds would be disqualified, and thus you would use your second attempt when calculating your total.

Thus, your results would look like this:

Squat: 400 pounds

Bench Press: 300 pounds

Deadlift: 450 pounds

And the math would look like this:

400 + 300 + 450 = 1,150 pounds

All powerlifting competitions follow this basic format, but there are many divisions of powerlifting which allow you to use more or less equipment to aid your lifting.

In the raw division, you’re allowed to use a belt, squat shoes, wrist wraps, and knee and elbow sleeves, but no other equipment. Many people consider this the most “pure” kind of powerlifting, since you only use a bare minimum of equipment to aid your lifts.

Here’s what a lifter in the raw division typically looks like:

In the classic raw division, you’re allowed to use everything from the raw division as well as knee wraps, which allow you to lift slightly more weight.

Here’s what a lifter competing in the classic raw division typically looks like:

In the single or double ply divisions, you’re allowed to use everything from the classic raw division as well as specialized weightlifting suits that are either one layer (single ply) or two layers (double ply) thick. These suits allow you to lift significantly more weight than you would be able to otherwise.

Here’s what a powerlifting suit for squatting and deadlifting looks like:

And here’s what a powerlifting suit for bench pressing looks like:

Most people new to powerlifting compete in the raw division because it requires the least equipment, but there’s nothing wrong with competing in other divisions, too.

There are also strict rules regarding how you perform each exercise.

- For the squat, you have to do a barbell back squat.

You can position the bar however you want on your back—up on your traps or down across your shoulder blades—but you can’t put it across the front of your shoulders like a front squat, and you can’t do single leg squats. You also have to do full range of motion squats, which means your hip bone is slightly below your knee cap when you’re at the bottom of each rep, like this:

View this post on Instagram

- For the bench press, you have to do a flat barbell bench press.

You can hold the bar as wide or narrow as you like or with a thumbless or normal grip, but you can’t do a reverse grip bench press, incline bench press, or dumbbell bench press. You also have to bring the bar all the way down until it touches your chest and have to keep your feet in contact with the floor and your butt in contact with the bench throughout the entire rep, like this:

View this post on Instagram

- For the deadlift, you have to do either a conventional or sumo barbell deadlift.

Which one you choose just comes down to personal preference. Regardless of which style you choose, you have to lift the bar until your back is more or less perpendicular to the floor and the bar can’t go any higher without lifting it with your arms or leaning backward, like this:

View this post on Instagram

Typically, powerlifters spend the bulk of their training time practicing the “big three”—the squat, bench press, and deadlift. They do most of their sets in the 1-to-5 rep range, resting anywhere from 2 to 10 minutes between sets, or as long as they require to fully recover before the next set. (A common joke in the powerlifting word is, “If it’s over 5 reps, it’s cardio.”)

Most powerlifters also do a few “accessory” exercises to aid their main lifts, such as Romanian deadlifts, Bulgarian split squats, incline bench press, and so forth.

Powerlifters also tend to plan and even periodize their training months in advance, working on building muscle and strengthening weak points several months before a competition, and working on getting as strong as possible on the squat, bench press, and deadlift as they approach the competition.

Powerlifting is often confused with Olympic weightlifting, but they’re very different sports.

Olympic lifting involves lifting as much weight overhead as possible using two different exercises: the snatch and the clean and jerk.

We don’t need to get into the nitty gritty details, but the long and short of Olympic weightlifting is that it’s a much more technical sport than powerlifting that requires a great deal more coordination and balance, and is judged by very different rules.

Summary: Powerlifting is a sport that involves lifting as much weight as possible for a single repetition of the squat, bench press, and deadlift in a single day. You get three attempts to lift as much weight as possible for each exercise, and your best attempt for each one is added together to give you your powerlifting total.

Can You Build Muscle with Powerlifting?

Many people believe that lifting heavy weights is only for getting stronger or competing in a sport like powerlifting, whereas lifting lighter weights for more repetitions is better for building muscle.

While there’s a kernel of truth to this idea, it’s mostly wrongheaded.

You see, the truth is you can build muscle effectively using a wide variety of rep ranges, including both very few (3 to 5) and very many (15 to 20) reps per set.

A good example of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at City University of New York.

The scientists split 20 resistance-trained men aged 20 to 31 years old into two groups:

- Group one performed 3 sets of 8 to 12 reps with 90 seconds of rest between each set for all of their exercises. This was the “hypertrophy” group.

- Group two performed 7 sets of 2 to 4 reps with 3 minutes of rest between each set for all of their exercises. This was the “strength training” group.

Everyone performed a 3-day per week push pull legs workout routine that involved the flat and incline bench press and machine flye, wide- and close-grip lat pulldown and seated cable row, and barbell squat, leg press, and leg extension.

The scientists adjusted the participants’ training so that both groups lifted about the same amount of total weight (sets x reps x weight) each week. They also continually increased everyone’s weights so that they were reaching muscular failure on every set and getting stronger week to week.

Before and after the study, the scientists measured the participant’s one-rep max for the bench press and squat, and measured their biceps thickness with ultrasound as a proxy for muscle growth.

All of the participants followed this workout routine for eight weeks. By the end of the study, both groups’ biceps had grown 13%, with no difference between the two groups.

Group two, though, added 25 pounds to their bench and 60 pounds to their squat, whereas group one only added 18 pounds to their bench and 48 pounds to their squat.

When this study came out, the pro-powerlifting crowd touted it as definitive proof that powerlifting is just as good for building muscle as bodybuilding-style training. And it does sort of show that—the group doing low reps gained just as much muscle and more strength than the group doing high reps.

On the other hand, there are a few other aspects of this study that should give you pause before you start using low reps and heavy weights for all of your training:

- Group one, the high-rep group, finished their workouts in about 17 minutes, whereas group two, the low-rep group, finished their workouts in 70 minutes. From a time efficiency standpoint, the higher rep group won.

- The differences in strength gains weren’t all that significant between the groups, and the difference in squat strength wasn’t statistically significant, either.

- Everyone in the low-rep group felt like they’d been thrown down a stairwell by the end of the study. To quote the lead author of the study, Brad Schoenfeld, “Almost all of them complained of sore joints and general fatigue, and the two dropouts from this group were because of joint-related injury (and these routines were highly supervised with respect to form, so we took every precaution for safety). On the other hand, the HT [hypertrophy] group all felt they could have worked substantially harder and done more volume.”

So, what are you supposed to make of all of this?

Well, first of all, it does indicate that you can effectively build muscle with powerlifting-style training. It also indicates powerlifting leads to greater strength gains over time than bodybuilding.

That said, this study also shows that doing all of your sets with low reps and heavy weights is a recipe for burnout, injury, and a lot of waiting around in the gym between sets.

This is why most powerlifters carefully plan their training in such a way that they’re splitting their training between lighter weights and higher reps and heavier weights and lower reps. The heavier weight, low rep training helps them gain strength, and the lower weight, higher rep training helps them do more volume and build more muscle without burning themselves out.

This way, they get the best of both worlds.

You’ll get an example of what this kind of program looks like in a moment.

The bottom line is that you can build muscle with powerlifting, but you’ll make better progress over time if you also incorporate lighter weight, higher rep sets into your training.

Summary: Powerlifting is highly effective for building muscle, but you also want to do some of your sets with lighter weights and higher reps to reduce the risk of getting burned out or injured.

Is Powerlifting Dangerous?

Many people think powerlifting is inherently dangerous, and I understand why.

When you compare squatting, bench pressing, and deadlifting gargantuan amounts of weight to other forms of exercise, like jogging, cycling, or calisthenics, weightlifting looks more like a death wish than a discipline.

Ironically, though, research shows that it’s actually one of the safest kinds of exercise you can do . . . when it’s done properly.

Proof of this comes from a review study conducted by scientists at Bond University that involved 20 different studies on injury rates from sports such as bodybuilding, strongman, Crossfit, and powerlifting.

The scientists found that on average, powerlifters suffered only one injury per 1,000 hours of training.

To put that in perspective, if you spend five hours per week weightlifting, you could go almost four years without experiencing any kind of injury whatsoever.

The scientists also noted that most of the injuries tended to be minor aches and pains that didn’t require any type of special treatment or recovery protocols. In most cases, they were fit as a fiddle after some rest.

Now, as we move into more intense and technical types of weightlifting, like CrossFit, Olympic weightlifting, and powerlifting, the injury rate rose, but not nearly as much as you might think. These activities produced just 2 to 4 injuries per 1,000 hours of training.

For comparison, sports like ice hockey, football, soccer, and rugby have injury rates ranging from 6 to 260 per 1,000 hours, and long-distance runners can expect about 10 injuries per 1,000 hours of pavement pounding.

In other words, you’re about 6 to 10 times more likely to get hurt playing everyday sports than hitting the gym for some heavy weightlifting—and that goes for powerlifting, too.

If you want to learn more about your risk of getting injured from lifting weights, and what you can do to avoid getting injured, read this article:

How Dangerous Is Weightlifting? What 20 Studies Have to Say

Summary: You’re much less likely to get injured powerlifting than you are compared to participating in most other sports, and most of the injuries people get from powerlifting tend to be minor and heal quickly.

How to Train for Powerlifting

Poke around on Google, Reddit, and weightlifting blogs and forums, and you’ll find enough powerlifting programs to make your head spin.

Some people say you should stick with something minimal like Starting Strength until that stops working.

Others say you should use the most challenging program you can tolerate, such as Sheiko, Smolov, Westside Barbell, or the Bulgarian method.

Read further, and you’ll find many other training programs pieced together by lifters over the years, such as Mad Cow, PHAT, GZCL, and others.

And then, of course, almost every high-level powerlifter has a proprietary training program for sale, too.

Which one should you choose?

Well, instead of reviewing each and every program and weighing the pros and cons, it’s better to look at the underlying principles that make all good powerlifting programs tick. Then, once you have these taped, it’s much easier to pick and choose which powerlifting programs are worth trying.

Here are the three principles shared by all good powerlifting programs:

- Specificity

- Progressive overload

- Recovery

(This is an oversimplification and there are many facets of powerlifting we could go over, but these are the biggies).

Specificity refers to training in a way mimics what you’ll do in competition as closely as possible. In powerlifting, this means spending the lion’s share of your time in the gym doing a lot of heavy squatting, bench pressing, and deadlifting.

Why? Well, no matter how much other exercises might help your powerlifting total, nothing is going to move the needle like squatting, bench pressing, and deadlifting.

For example, getting really strong on front squats is a great way to build your quads, but it’s not going to improve your back squat as much as back squatting. Barbell rows are a great back exercise, but they won’t help your deadlift as much as deadlifting. And although dumbbell bench press is a phenomenal chest exercise, it won’t improve boost your bench press as much as bench pressing.

Not only is exercise specificity important, but rep range specificity matters, too. Your strength is largely specific to the rep ranges you practice the most in your training, so you want to spend a good chunk of your training time working in lower rep ranges. This is especially true for your squat, bench press, and deadlift, as the whole point of powerlifting is getting as strong as possible for a single rep of all of these exercises.

Progressive overload refers to increasing the amount of tension your muscles produce over time, and the most effective way to do this is by progressively increasing the amount of weight that you’re lifting.

In other words, the key to gaining muscle and strength isn’t doing a laundry list of different exercises, balancing on a BOSU ball, or seeing how much you can sweat on everything in the gym, and this is particularly true in powerlifting.

The key to getting stronger and building muscle is forcing your muscles to work harder over time. This is exactly what you do when you gradually force them to handle heavier and heavier weights and do more sets.

Recovery, also sometimes referred to as fatigue management, refers to strategically incorporating rest into your training program in a way that allows you to adapt to your workouts and become stronger over time.

This is one of the most underrated aspects of proper training not just for powerlifting, but for any sport. Perhaps the number one mistake made by newbie lifters is doing too much, too soon, and either getting burnt out, injured, or simply progressing slower than they should.

Proper recovery encompasses . . .

- Eating enough calories and protein

- Getting enough sleep

- Allowing time for each muscle group to mostly recover before training it again

- Incorporating deloads and planned time off every few months

If you get these three things right, then you’re going to be ahead of 90% of people who are interested in powerlifting.

I’ve trained in many, many different sports and known many highly successful athletes, and one of the cardinal rules they all eventually learn is that to make progress, you have to take your rest just as seriously as your training.

Understanding all three of these principles also makes it much easier to pick an effective powerlifting program that’s right for you.

For example, an extremely high-volume powerlifting program like Smolov can work well for an experienced lifter who can tolerate large volumes, but it’s generally going to be far, far too much progressive overload and too little recovery for a beginner.

Likewise, a simple, low-volume strength training program like Starting Strength could provide the right mix of specificity, progressive overload, and recovery for a beginner, but would likely be far too easy for an experienced powerlifter.

Once you grasp these principles, you can see why the “best” powerlifting program for someone else might not be the best one for you.

The best powerlifting program for you depends on your goals, your training experience, your ability to recover from your workouts, and your preferences.

Summary: To be successful at powerlifting, you have to spend the majority of your time practicing the squat, bench press, and deadlift, you have to focus on getting as strong as possible on a single repetition of all of these exercises, and you have to rest enough to effectively recover from your workouts.

What’s the Best Powerlifting Program for You?

If you’re reading this article, I’m going to assume that you’re relatively new to powerlifting or strength training on the whole.

In that case, I recommend you stick to the following guidelines when setting up your powerlifting training. These come from Eric Helms, PhD, who’s a powerlifting and bodybuilding coach, drug-free powerlifter and bodybuilder, and member of the Legion Scientific Advisory Board.

In terms of training frequency, or how often you train the squat, bench press, and deadlift, Eric recommends most beginners train each lift two to three times per week. This lets you practice these lifts often enough to quickly improve your skill, while still allowing plenty of time for recovery.

In terms of volume, or sets per week, Eric recommends you aim for around 10 to 20 sets each of squatting, bench pressing, and deadlifting per week.

In terms of rep ranges, Eric recommends you do about 60 to 80% of your sets in the 1-to-6-rep range and about 20 to 40% of your sets in the 6-to-15-rep range.

In terms of rest periods, Eric recommends you rest as long as you need to between sets to ensure you’ve fully recouped your strength and can exert maximum effort on the next set.

And in terms of intensity, Eric recommends you do all of your sets about 0 to 5 reps from failure. In general, you’ll take your squat, bench press, and deadlift about 1 to 3 reps shy of failure, and your accessory exercises 2 to 5 reps shy of failure.

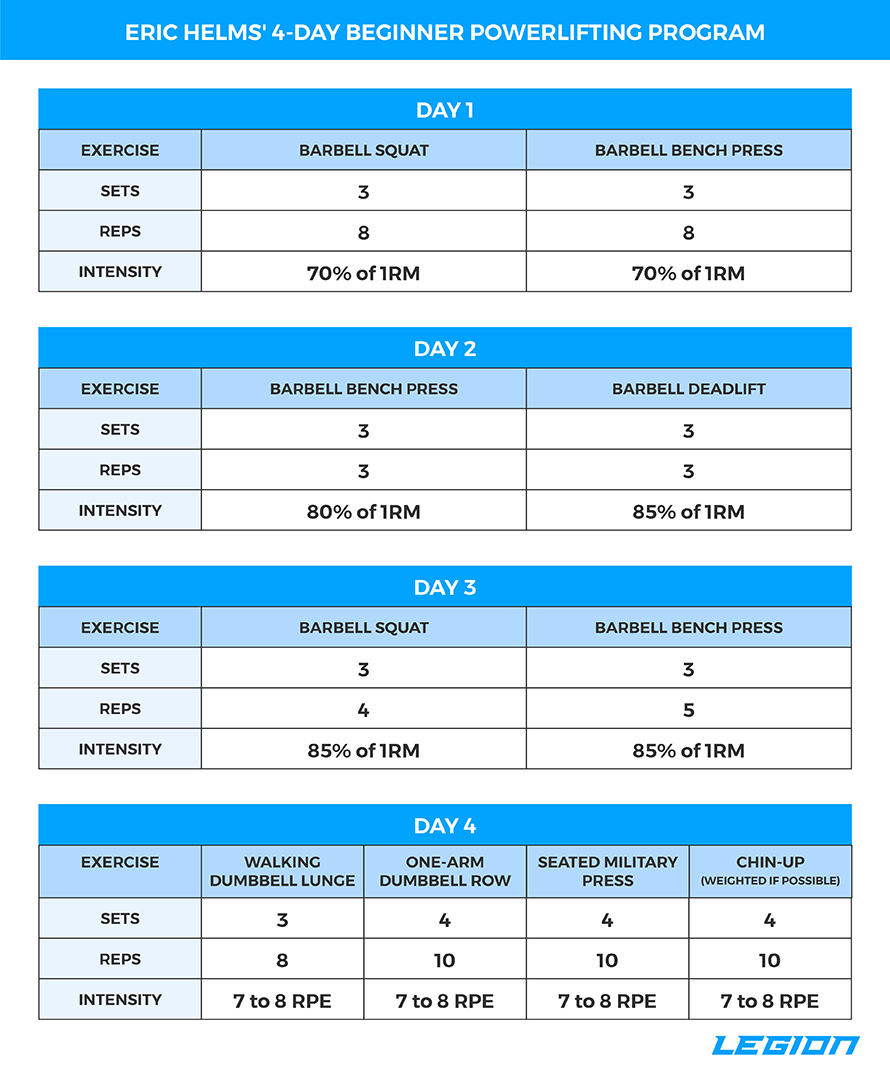

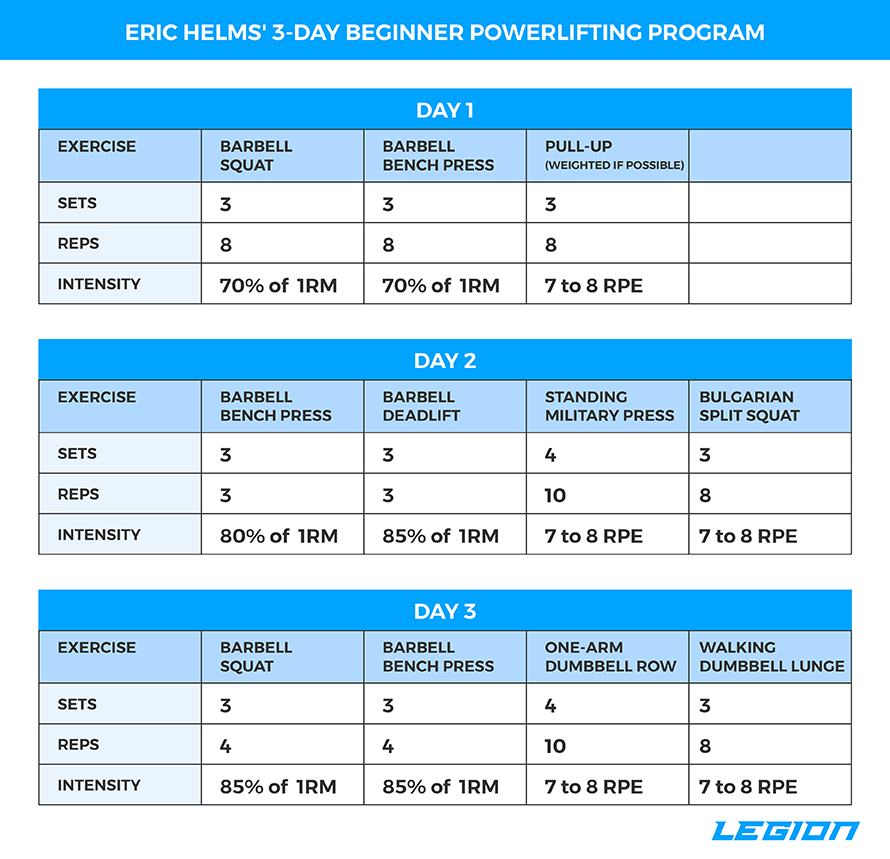

There are many good powerlifting programs to choose from, but one that fits these guidelines particularly well also comes from Eric’s book, the Muscle and Strength Training Pyramid.

Eric includes both a 3-day and a 4-day per week novice powerlifting program in the book.

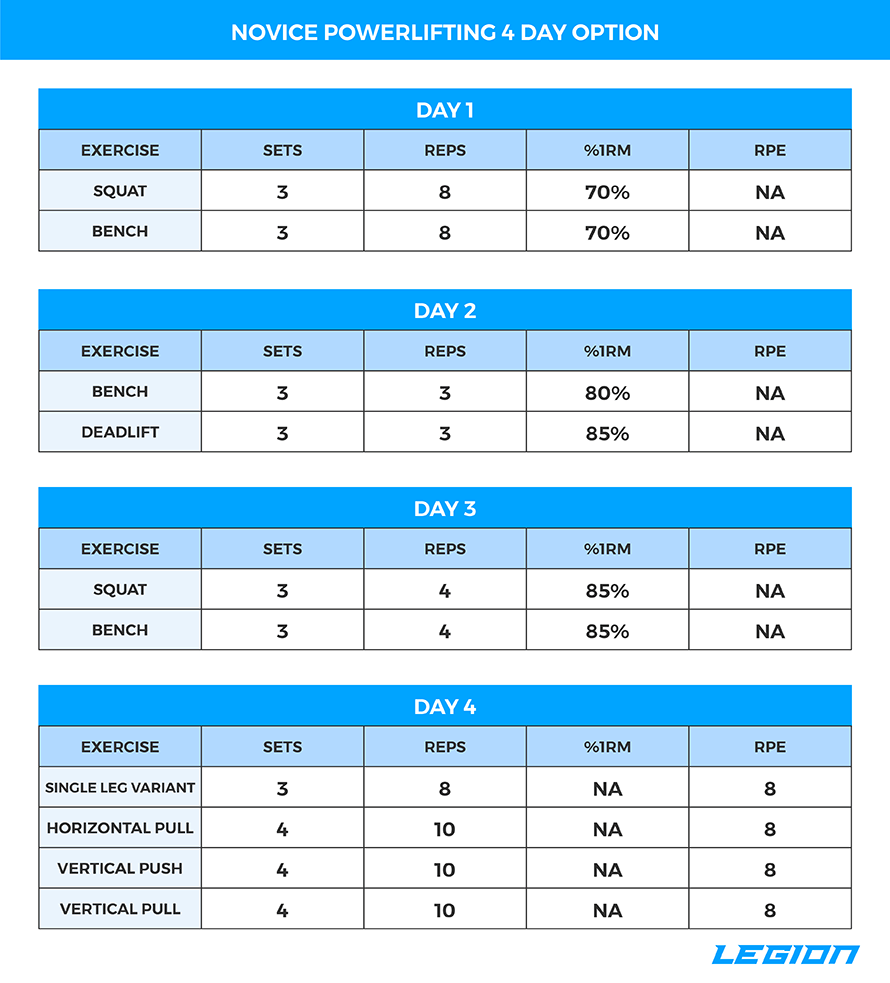

Here’s the 4-day per week plan, which is what I recommend you follow if you have the time:

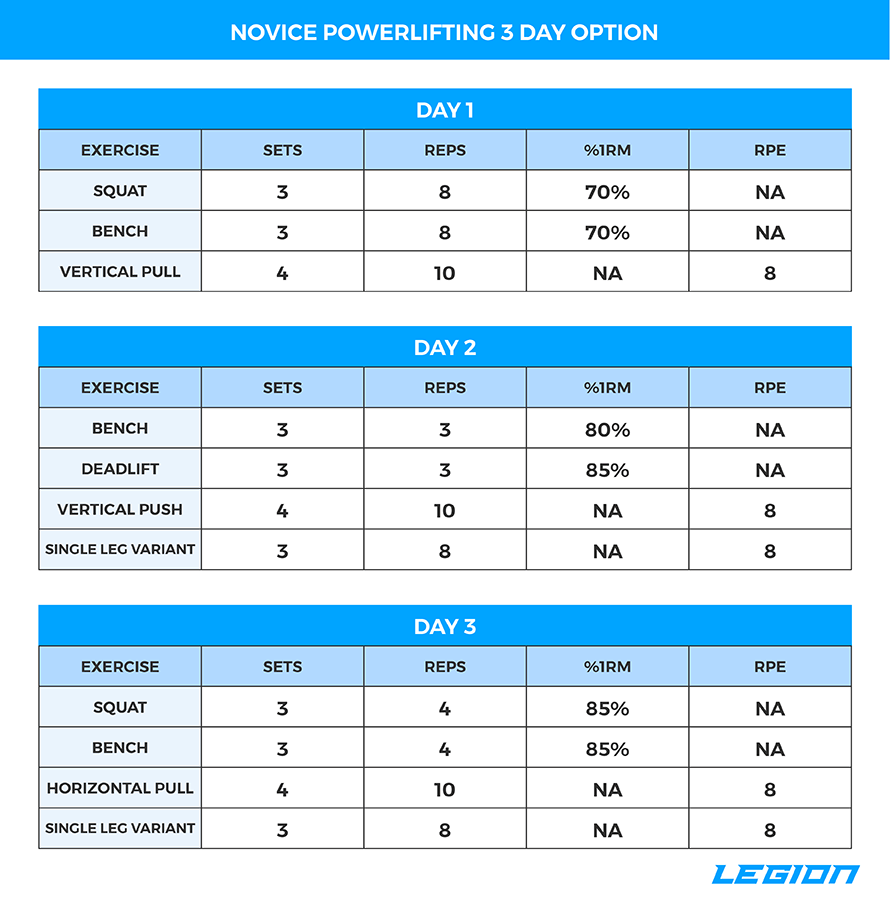

And here’s the 3-day per week plan, which is a good option if you’re on a time-crunched schedule:

A few notes on how to set up this program:

A few notes on how to set up this program:

- Eric intentionally left some of the exercise recommendations open-ended. For example, the “SL Variant” on day 4 of the 4-day per week plan stands for a single-leg variant of the squat. You could do Bulgarian split squats, dumbbell lunges, single-leg barbell squats, or whatever you like. As long as it’s a single-leg compound exercise that’s similar to a squat, it’s fair game.

- Eric provided two different ways of measuring your exercise intensity: % of 1RM and RPE.

It’s worth spending a moment to understand these two concepts, as they’re used in many powerlifting programs.

A one-rep max is the maximum amount of weight you can lift for a single repetition of a given exercise through a full range of motion with proper technique. Knowing your one-rep max helps you maintain optimal workout intensity (and thereby achieve optimal results).

Once you know your one-rep max, you can decide how much weight to use in your workouts based on a percentage of that number. For example, on Day One of Eric’s 4-day per week plan, you’re doing squats with 70% of your one-rep max. If your one-rep max is 300 pounds, that means you’ll be squatting with 210 pounds. (300 x 70% = 210).

Read this article to learn more about how to use your one-rep max in your training:

A Simple and Accurate One-Rep Max Calculator (and How to Use it)

The problem with using percentages of your one-rep max, though, is that calculating and tracking your one-rep max for some exercises isn’t very practical. For example, estimating a one-rep max for an isolation exercise like the barbell curl is tricky and often prone to error. As isolation exercises like this also aren’t as critical to your success as a powerlifter, it’s also not as important to use a fancy percentage-based progression system like it is for your squat, bench press, and deadlift.

This is where RPE comes in handy. RPE stands for rating of perceived effort, and it’s a subjective measurement of how hard an exercise feels at the end of a set, usually on a scale of 1 to 10.

For example, on Day Four of Eric’s powerlifting program, all of your exercises should be done with a 7 to 8 RPE. Thus, by the end of each set, you should feel like you’re working at about a 7 or 8 on a scale of 1 to 10 in terms of effort.

If you’re having trouble determining how much weight you should use according to RPE, here’s a little exercise to help:

At the end of a set, just before re-racking your weights, ask yourself, “If I absolutely had to, how many more reps could I have gotten with good form?”

A 7 to 8 RPE means you should be able to get at least two to three more reps with good form if you absolutely had to.

If you don’t think you could have gotten at least two to three more reps, then you should lower the weight by 10 pounds for that exercise on the next set. If you think you could have gotten four or more reps, increase the weight by 10 pounds for that exercise on the next set.

In this way, you can use RPE to add or subtract weight for certain exercises based on how you feel.

Read this article to learn more about how to use RPE in your training.

This Is the Best Guide to the RPE Scale on the Internet

With that out of the way, here’s how I generally like to set up Eric’s 4-day per week novice powerlifting program:

And here’s how I usually go about setting up Eric’s 3-day per week novice powerlifting program:

Let’s go over a few more notes on how to do this program.

Warm up before each workout.

Before your first set of your first exercise of each workout, make sure you do a thorough warm-up.

A warm-up accomplishes several things:

- It helps you troubleshoot your form and “groove in” proper technique (which is particularly important when you’re learning a new exercise).

- It can significantly boost your performance, which can translate into more muscle and strength gain over time.

In weightlifting, a warm-up consists of doing one or two light sets of an exercise, followed by one or two heavier sets until you’re using a weight that’s about 70% as heavy as the heaviest weight you’ll use that day for that particular exercise.

Here’s how to warm up properly:

Do several warm-up sets with the first exercises for each of the muscle groups you’re training in that day’s workout.

For example, in Day One workout of the 4-day workout routine, your first exercise is the barbell squat, which primarily trains your legs, hips, and back. The next exercise is the bench press, which primarily trains your chest, arms, and shoulders. Thus, squatting isn’t going to do a great job of warming up the muscles involved in bench pressing, so it makes sense to do two separate warm-ups: one before you start your heavy sets of squatting, and one before you start your heavy sets of bench pressing.

Here’s what this would look like:

Barbell Squat

Warm-up

Set 1

Set 2

Set 3

Barbell Bench Press

Warm-up

Set 1

Set 2

Set 3

Now, let’s say you’re doing seated military press on Day Four of the 4-day workout routine. In this case, you’ve already warmed up for your one-arm dumbbell rows, which train many of the same muscle groups (indirectly), so you probably won’t benefit much by doing another warm-up before your sets of barbell military press.

Here’s the protocol you’re going to follow for the workouts in this article:

- Estimate roughly what weight you’re going to use for the three sets of your first exercise (this is your “hard set” weight). Let’s say you’re doing barbell squats on Day One of the 4-day workout routine for this example.

- Do 10 reps with about 50 percent of your hard set weight, and rest for a minute or two.

- Do 10 reps with the same weight at a slightly faster pace, and rest for a minute or two.

- Do 4 reps with about 70 percent of your hard set weight, and rest for a minute or two.

Then, do all three of your hard sets for your barbell squats, and then repeat the same warm-up procedure for your barbell bench press, before doing all three hard sets of bench press.

If you want to learn more about the importance of a proper warm-up and how to warm up for different workouts, check out this article:

The Best Way to Warm Up For Your Workouts

Try to do no more than two workouts in a row before taking a rest day.

For example, many people like to set up their 4-day workout routine like this:

Monday: Day 1

Tuesday: Day 2

Wednesday: Rest

Thursday: Day 3

Friday: Day 4

Saturday: Rest

Sunday: Rest

And their 3-day workout routine like this:

Monday: Day 1

Tuesday: Rest

Wednesday: Day 2

Thursday: Rest

Friday: Day 3

Saturday: Rest

Sunday: Rest

This ensures you get enough recovery between each workout to progress over time.

Try to add weight to every exercise every time you train.

You won’t necessarily do this every time you set foot in the gym and you don’t want to sacrifice good technique to increase the weight, but you should be adding weight to every exercise over time.

Make sure you eat enough food.

If you want to gain strength and muscle as quickly as possible, then you need to eat enough calories to recover from your workouts. If you don’t, you simply won’t progress as fast as you should.

Read this article to learn how many calories you should eat:

How Many Calories You Should Eat (with a Calculator)

Deload every 3 to 6 weeks, depending on how you feel.

If you’re eating enough calories, sleeping enough, and staying one or two reps shy of failure, but still feeling beat up and sore, take a deload. If you’re feeling good and progressing on most of your exercises, keep going.

Read this article to learn how to deload:

How to Use Deloads to Gain Muscle and Strength Faster

The Bottom Line on Powerlifting

Powerlifting is a sport that consists of lifting as much weight as possible on the squat, bench press, and deadlift for a single repetition.

In a powerlifting meet, lifters take turns lifting as much weight as they can on the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Whoever is able to lift the most weight on these three exercises wins the meet.

Many people believe that lifting heavy weights is only for getting stronger or competing in a sport like powerlifting, lifting lighter weights for more repetitions is better for building muscle.

The truth is that heavy, low-rep weightlifting, like powerlifting, is an extremely effective way to build muscle. The downside is that this kind of training also tends to be harder on your body, which is why most powerlifters supplement their heavy, low-rep training with lighter, higher-rep training.

Although many people think powerlifting is inherently dangerous, the reality is that it’s one of the safest forms of exercise you can do, when done properly.

There are many good powerlifting programs to choose from, but they all follow three basic principles:

- Specificity

- Progressive overload

- Recovery

The right mix of these principles depends on your goals, how long you’ve been training, what you enjoy, and how well you recover from powerlifting-style workouts.

If you’re new to powerlifting, both Eric Helms’ 4-day per week and 3-day per week novice powerlifting programs are outstanding places to start.

Warm up before each workout, allow sufficient rest between your workouts, try to add weight to every exercise week to week, make sure you eat enough food, and deload every 3 to 6 weeks, and you’ll get stronger and stronger.

Happy lifting!

What’s your take on powerlifting? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Fradkin AJ, Zazryn TR, Smoliga JM. Effects of warming-up on physical performance: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(1):140-148. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c643a0

- Gabriel DA, Kamen G, Frost G. Neural adaptations to resistive exercise: Mechanisms and recommendations for training practices. Sport Med. 2006;36(2):133-149. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636020-00004

- Schoenfeld BJ, Ratamess NA, Peterson MD, Contreras B, Sonmez GT, Alvar BA. Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(10):2909-2918. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480

- Videbæk S, Bueno AM, Nielsen RO, Rasmussen S. Incidence of Running-Related Injuries Per 1000 h of running in Different Types of Runners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med. 2015;45(7):1017-1026. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0333-8

- Moore IS, Ranson C, Mathema P. Injury Risk in International Rugby Union: Three-Year Injury Surveillance of the Welsh National Team. Orthop J Sport Med. 2015;3(7). doi:10.1177/2325967115596194

- Spinks AB, McClure RJ. Quantifying the risk of sports injury: A systematic review of activity-specific rates for children under 16 years of age. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(9):548-557. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.033605

- Keogh JWL, Winwood PW. The Epidemiology of Injuries Across the Weight-Training Sports. Sport Med. 2017;47(3):479-501. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0575-0

- Schoenfeld BJ, Ratamess NA, Peterson MD, Contreras B, Sonmez GT, Alvar BA. Effects of different volume-equated resistance training loading strategies on muscular adaptations in well-trained men. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(10):2909-2918. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000480

- Burd NA, West DWD, Staples AW, et al. Low-Load High Volume Resistance Exercise Stimulates Muscle Protein Synthesis More Than High-Load Low Volume Resistance Exercise in Young Men. Lucia A, ed. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12033. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012033