Key Takeaways

- Periodization is a method of organizing your training that involves emphasizing different aspects of your fitness at different times.

- Most periodization systems are best suited to intermediate and advanced weightlifters, not beginners.

- A simple way to periodize your training is to gradually increase intensity (load) and decrease volume (sets or reps) as you move through training period, deload, and repeat.

Periodization is a hotly debated topic in many weightlifting circles.

It’s also a muddled one that’s hard to navigate unless you already have quite a bit of specialized knowledge.

For starters, it’s hard to find a consistent, simple definition of what periodization even means.

Some say it means changing your rep ranges every so often. Others say it means taking planned deloads. Others still say it means continually changing your exercises.

And regardless of how it’s defined, there’s often a debate as to its merits.

One school of thought claims periodization isn’t a fundamental component of effective training, like progressive overload, but instead an advanced tactic for scaling the final summit of your genetic potential, in the same vein as supersets, rest-pause sets, blood flow restriction, and the like.

According to another line of thinking, however, more or less everyone should be following a periodized workout plan, and if you aren’t, you’re missing out.

Who’s right?

The short answer is periodization is a valuable technique for lifters of all stripes and ability levels, and you should include at least some form and degree of it in your training.

That said, most periodization systems are best suited to intermediate and advanced weightlifters, not beginners.

And in this article, you’ll learn why, including . . .

- What periodization is

- Why people periodize their training

- Whether you should periodize your training

- The best kinds of periodization

- An easy and effective way to use periodization to gain muscle and strength faster

- And more

Let’s begin.

What Is Periodization?

Periodization refers to how you organize your training over time, typically leading up to a competition or an attempt to set a new personal record.

At bottom, periodization splits your training into different periods (hence the word) in which you focus on different aspects of your fitness.

For example, if you’re preparing for a powerlifting meet, you want to focus on heavy, low-rep compound training in the month or two before the competition, so your muscles are primed for the demands of the meet.

Read: The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide to Powerlifting (With a Free Training Plan!)

The month or two before that, however, you might do lighter, higher-rep training, with more accessory exercises to strengthen the same muscles you use to squat, bench press, and deadlift.

Hence, your training would be periodized, as you’d be working in different rep ranges on different exercises over two to four months as you focus on different goals.

While there are many theories on the best way to periodize your weightlifting, the most viable ones are all based on a few simple principles:

1. Your training involves progressive overload in the form of more weight, sets, or reps (with weightlifting), or faster pacing, longer distances, more complex movements, less rest, or some other method in other activities.

2. Your training shifts from less specific to more specific as you progress through the plan. With weightlifting, since competitions involve lifting very heavy weights for single reps, this principle generally means progressing from lighter weights and higher reps (less specific to the sport) to heavier weights and lower reps (more specific).

3. Your training includes planned breaks to allow for additional rest and recovery.

When used correctly, this approach allows you to thread the needle between stress and recuperation, by providing enough stimulus in the way of volume and weight to keep progressing, but not so much as to court injury, overtraining, or burnout.

This is why athletes of all stripes, including bodybuilders, powerlifters, gymnasts, cyclists, runners, swimmers, basketball, football, and soccer players, and even golfers, handball players, and surfers, use periodization in their training.

Summary: Periodization refers to how you organize your training over time, and periodized training involves spitting your training into different periods in which you focus on different aspects of your fitness.

How Does Periodization Work?

To understand how periodization works, it helps to grasp a bit of its history, which stretches back to research conducted in the early 1950s by a Hungarian endocrinologist named Hans Selye.

Selye developed a theory about how we respond to stress known as the general adaptation syndrome, which states that the body responds to stress—including exercise—in three phases:

- Alarm, where the body initially responds to the stressor (increased heart rate, stress hormones, etc.).

- Adaptation, where the body recovers and gets stronger if given enough rest.

- Exhaustion, where the body fails to recover and gets weaker because of too little rest.

As an athlete or someone who just hopes to get more jacked, you want to repeatedly alarm your body and then allow it to adapt, while staying away from the exhaustion phase.

Inspired by Selye’s findings, Russian physiologist Leo Matveyev began analyzing the training programs of successful and unsuccessful Soviet athletes from the 1952 and 1956 Summer Olympics. He found that either deliberately or accidentally, the most successful athletes in a variety of sports trained according to the principles of Selye’s theory.

They pushed themselves to become stronger, faster, and more skilled, often to the limits of their ability, and then reduced training intensity or volume to allow for more rest and recovery.

Additionally, their training was planned in undulating cycles of first honing the fundamentals and then focusing on competition-specific workouts.

Matveyev organized and codified these practices, creating a system we now know as linear periodization. With weightlifters, this approach called for increasing intensity and decreasing volume as they approached their competitions, with planned breaks throughout to avoid overtraining.

Matveyev’s system was adopted across the USSR and East Germany to great effect—these countries quickly became the dominant forces in Olympic lifting and many other sports, and they stayed on top for the next several decades.

Although later systems of periodization implement these principles in slightly different ways, virtually all have their origin in Matveyev’s work. In most cases, training is broken up into three distinct phases or periods.

1. First, you have the longest phase, the macrocycle, which is a long-term view centered around preparing for a particular event or improving body composition or physical conditioning.

For recreational weightlifters, this generally means setting a new personal record or gaining muscle or losing fat.

Macrocycles can last anywhere from a few months to several years, depending on the activity, individual, and goals. In bodybuilding, they typically last three to six months (around the length of a typical lean bulking or cutting cycle).

2. The second longest phase is the mesocycle, which focuses on developing a particular skill or quality (muscle growth, strength, etc.).

A mesocycle usually lasts one to four months, so in bodybuilding, there are often a couple of mesocycles within each macrocycle.

3. The shortest phase is the microcycle, and it’s typically defined as a several-day period of vigorous training followed by a short period of lighter training or rest.

For example, you might train five days per week and take two days off, which would be a seven-day microcycle. A microcycle normally comprises a week’s worth of training, but some people use shorter or longer microcycles.

Summary: Periodization refers to how you organize your training over time, and generally involves creating plans that revolve around macrocycles, mesocycles, and microcycles.

Why Do People Periodize Their Training?

The main reason people periodize their training is it helps them make faster, more consistent progress than with non-periodized training.

To understand why, you have to understand how most people get on in their weightlifting journey.

When they first begin, progress is easy, and especially if they’re following a well-designed workout routine. They simply show up to the gym a few times per week, get a couple more reps or lift a little more weight than the last time, eat halfway intelligently, and get bigger and stronger.

It can go like this for the first six months or even longer, and during this period, there’s often no need for deloading or taking special precautions to avoid getting injured.

There are two reasons for this “honeymoon phase”:

- When you’re new to weightlifting, your body is primed to gain muscle and strength quickly.

- The weights you’re lifting often aren’t heavy enough to pose any major risk of injury.

These “newbie gains” only last for so long, however, and eventually come to an end, and you enter your intermediate phase.

At this point, progress slows dramatically and the risks of poor technique and programming rise as well as the likelihood of hitting a plateau where you simply aren’t gaining any muscle or strength to speak of anymore.

Many people who get their first case of the ruts respond by simply training harder. They train to failure more often. They do more sets. They try harder exercise variations and rep schemes.

This can lift them out of the doldrums, but it also starts to take its toll on their body in the form of achy joints and tendons, weakened motivation, impaired sleep, and other symptoms related to overtraining.

Other people respond to a plateau by complacency. They keep showing up to the gym but just go through the motions, maybe adding a little weight when they feel good and removing a little when they don’t.

This allows them to maintain much of the muscle and strength they’ve gained, but more or less halts any further progress.

Periodization is an effective way to avoid these pitfalls.

Summary: Periodization balances training and recovery in a way that allows you to make consistent progress without getting stuck, injured, overtrained, or burned out.

Does Periodization Help You Gain Muscle and Strength?

Yes, but how you should go about it will depend on how experienced of a weightlifter you are.

For instance, if you’re new to lifting, all you need is a simple, linear style of periodization that has you striving to gain reps and add weight to the bar each week for a couple months or so before deloading and repeating.

Two good examples of this kind of training are my Bigger Leaner Stronger program for men and my Thinner Leaner Stronger program for women.

In these programs, you work within specific rep ranges, take hard sets to within a rep or two of technical failure, push to gain reps over your previous week’s workouts, add weight to the bar (or dumbbells) when you reach the top of your rep range, and deload and change up your exercises every 8 weeks.

Simple, straightforward, and powerfully effective, as evidenced by the hundreds of success stories from men and women of all ages and circumstances.

For example, check these guys and gals out . . .

These people (and many others) are living proof you don’t need a complicated periodization plan to get fantastic results in the gym. In fact, many people have used Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger for years before having to change things up.

Remember: When you’re a beginner, your body is so primed to build muscle that basic programming is all you need to maximize muscle growth. More advanced forms of training, including periodization, would simply be a distraction.

After your first year or two of that style of training, however, the game changes, and a more complex periodization plan makes more sense.

Good evidence of this is a study conducted by scientists at Appalachian State University that analyzed fifteen studies comparing periodized training programs to non-periodized programs. The researchers found that in thirteen out of the fifteen cases, people got stronger or improved their performance more with a periodized training plan versus a non-periodized one.

What’s more, the two studies that found periodization didn’t improve performance were shorter than the others and involved inexperienced trainees, who are the least likely to benefit from periodized training.

A meta-analysis conducted by scientists at the University of Alabama also supports these findings. The researchers reviewed eighteen studies from 1988 to 2015 on periodized and non-periodized training and strength gain.

After examining eighty-one datasets from these papers, the scientists concluded that “ . . . the magnitude of improvement in 1RM [one-rep max] following periodized resistance training was greater than non-periodized resistance training.”

In other words, on average, people who followed a periodized training plan got stronger than those who didn’t.

Finally, another piece of evidence in favor of periodization comes from an unpublished meta-analysis of just about every study on periodization and strength gain in the literature, conducted by Greg Nuckols.

After parsing through twenty-seven studies on the matter, Nuckols concluded that on average, periodized training plans helped people gain strength 22% faster than non-periodized plans.

He also addressed several studies whose abstracts seemed to show periodization isn’t helpful for gaining strength.

In almost every case, the scientists agreed periodized training leads to more strength gain and performance enhancement in most sports.

What they questioned were the most effective ways to use and study periodization and measure its benefits. Their disagreements were regarding the technical details of periodization, not its fundamental merits.

Another claim you may have heard is that periodization is good for improving strength, but not muscle growth. This isn’t entirely off base, but it isn’t exactly correct, either.

It’s true that most of the studies on periodization show it’s more effective for gaining strength than muscle, but most of these studies also only lasted four to eight weeks.

Because you can gain strength faster than muscle, this isn’t enough time for the muscle-building benefits of periodization to manifest in a statistically significant way—especially considering how slowly intermediate and advanced weightlifters gain muscle.

Read: Is Getting Stronger Really the Best Way to Gain Muscle?

For example, let’s say periodization can increase muscle gain by up to 10% over non-periodized training and that subjects in an eight-week study could gain 2.5 pounds of muscle with periodized training and about 2.25 pounds without periodization.

In most cases, that difference wouldn’t be statistically significant, but over enough time, it would add up to a real advantage.

There’s also a good reason to believe periodization would indeed increase muscle gain.

In fact, we’ve already discussed it: As you become a more experienced weightlifter, the most reliable way to gain muscle is to get stronger.

And as we know that periodization can boost strength gain, it’s reasonable to assume it can boost muscle growth, too.

Summary: Research shows periodization improves strength gain over time, and it probably increases muscle growth as well.

What Kind of Periodization Is Best?

There are many ways to periodize your workouts, and many opinions on which is best.

Some people say classic linear periodization is all we need. Others say undulating periodization is better. And still others say methods like block periodization, reverse linear periodization, or conjugate periodization is the clear winner.

Who’s right? Before we get into that, let’s define the most popular periodization systems out there.

- Linear periodization involves increasing intensity (weight) and usually reducing volume (sets) over the course of a macrocycle.

- Reverse linear periodization is like linear periodization, except each macrocycle starts with heavier weights and less volume and progresses to lighter weights and more volume.

- Undulating periodization involves changing the weights, reps, and sets you use day to day or week to week, but not the exercises.

- Block periodization focuses on a handful of exercises for one mesocycle (generally a month or two).

- Conjugate periodization involves changing your exercises, weights, reps, and sets day to day or week to week. This is similar to undulating periodization, but more haphazard.

Each of these systems also involves increasing the weights lifted over time, usually according to a regular pattern, like every workout or week, for instance.

So which method is the best? None of them.

First, although they have different names and protocols, they’re more alike than different in that each follows the same three principles you learned earlier:

- Progressive overload in the form of more weight, sets, or reps.

- Increasing specificity as you progress through the plan by moving from lighter weights and higher reps to heavier weights and lower reps or vice versa.

- Planning breaks to allow for rest and recovery.

Second, each method has inherent advantages and disadvantages, so instead of wedding yourself to one, it’s probably best to use a mix of different styles. And that’s not just my opinion, either—there’s strong evidence that mixing different periodization techniques is optimal for strength and muscle gain.

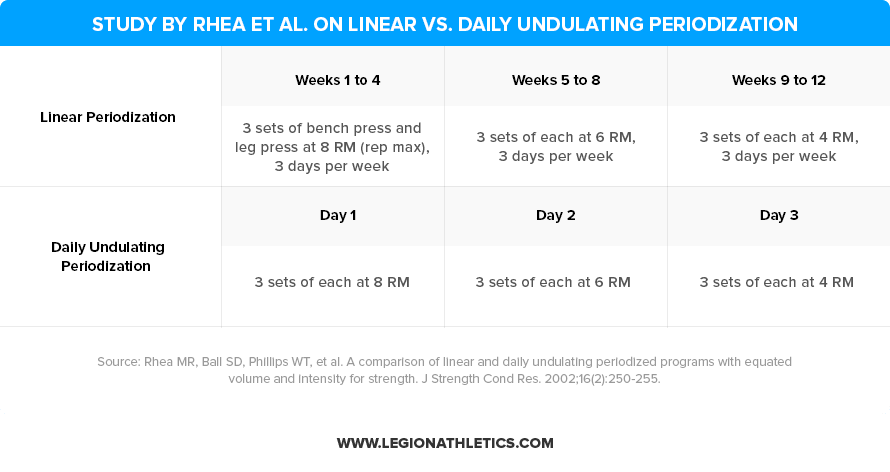

In a study conducted by scientists at Arizona State University, twenty 21-year-old weightlifters with an average of five years training experience were split into two groups:

- Group one followed a traditional linear periodization workout plan, which involved increasing intensity and decreasing volume throughout the study.

- Group two followed a daily undulating periodization plan, with a mix of high-intensity, low-rep and low-intensity, high-rep training throughout the week.

The scientists ensured both groups did the same number of reps and sets and the same exercises with the same technique, and they tested everyone’s bench press and leg press one-rep maxes before and after the twelve-week study.

Here’s what the two training plans looked like:

That is, everyone trained with weights between 80 and 90 percent of their one-rep max on each exercise, but group one spent a month at 80 percent, a month at 85 percent, and a month at 90 percent, whereas group two cycled through the different intensities each week.

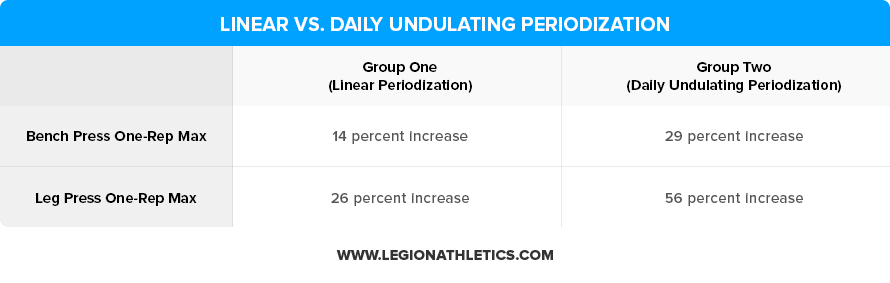

The results:

Group two gained nearly twice as much strength as group one, despite doing the same amount of work and spending the same amount of time in the gym.

The takeaway from this study and several others like it is varying your rep ranges over a shorter period produces better results than over a longer period. It’s not entirely clear why this is, but research suggests that training in different rep ranges stimulates different muscle-building mechanisms in the body. Therefore, by only training one rep range for long periods of time, you may fail to activate other “pathways” for muscle and strength gain.

So, should you reprogram your training to ensure you’re rotating through rep ranges every week? Not necessarily.

Remember—the participants in the study we just reviewed only did two exercises: The bench press and leg press. Most workout routines will involve more exercises, and unless you’re following a fairly high-frequency powerlifting program, you won’t be doing the same exercises more than once or twice per week.

For example, in the first week of the five-day routine of the Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger program, you bench press on day one (usually Monday), military press on day three (usually Wednesday), and incline bench press on day five (usually Friday).

If you were to follow the same daily undulating periodization plan as in the above study, you’d work with 80 percent of your one-rep max on the bench press, 85 percent on the military press, and 90 percent on the incline bench press.

I don’t like this setup for a couple of reasons:

1. You’re changing your exercises as well as your intensity and rep ranges, which adds complexity to your programming and is unlikely to improve your results.

The point of varying your rep ranges is to stimulate your muscles in different ways. You can accomplish the same thing with different exercises, but doing both at the same time is overkill.

As a general rule, I want my programming to be as simple as possible (or no more complicated than it needs to be), and changing rep ranges, intensities, and exercises throughout the week adds an unnecessary layer of complexity.

2. Some exercises don’t lend themselves to high- or low-rep training.

For example, most people find that anything above ten reps on the deadlift with heavy weight is grueling, if not dangerous, but not on the bench press. Similarly, a heavy set of five reps of dumbbell side raises is all kinds of awkward, whereas heavy biceps curling is perfectly viable.

Dumbbell exercises also rarely jibe with low rep ranges. For example, although you can do triples on the seated dumbbell overhead press with about 90 percent of your one-rep max, it’s difficult to get the dumbbells into position and potentially dangerous as you approach technical failure.

The bottom line on daily undulating periodization is this: it can work well if you’re doing the same exercises multiple times a week, like the people in the study mentioned were, but otherwise, there are better options.

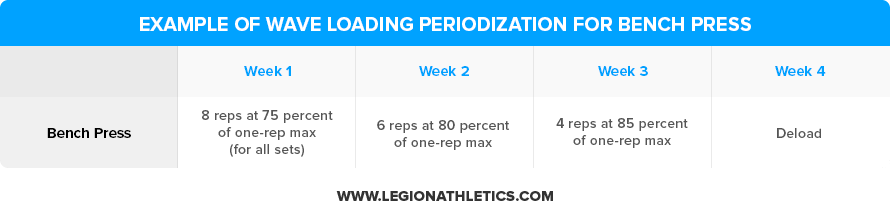

What I prefer most is referred to as weekly undulating periodization. Instead of changing your rep ranges and exercises throughout the week, you change one or both from one week to the next. For instance, here’s how you might use weekly undulating periodization with your bench press.

This approach has you increasing weight and reducing reps each week, which gives you the benefits of undulating periodization while also being easy to plan and track.

It gives you a different challenge to look forward to each week, as well, which can help keep your training interesting.

Another key element to effective periodization is ensuring you’re getting stronger. The weights you’re handling should go up from one macrocycle to the next, even if it’s just a slight increase.

My favorite way of accomplishing this is known as wave loading, which involves increasing the amount of weight you’re lifting over the course of a mesocycle or macrocycle (or both), punctuated by periodic reductions in intensity or volume to enhance recovery.

My favorite way of accomplishing this is known as wave loading, which involves increasing the amount of weight you’re lifting over the course of a mesocycle or macrocycle (or both), punctuated by periodic reductions in intensity to enhance recovery.

Practically speaking, all you need to do to accomplish this is to increase your training weights for the various exercises you do regularly from 2.5 to 10 pounds every mesocycle.

Here’s an example of wave loading over the course of three mesocycles.

Let’s say you’re going to use weekly undulating periodization for a 4-week mesocycle, and you start week 1 benching 225 pounds for 3 sets of 8 reps.

Then, on week 5—at the start of your second mesocycle—you’d use 230 or 235 pounds for 3 sets of 8 reps.

And then, in the first week of your third mesocycle, you’d use anywhere from 240 to 245 pounds for 8 reps, and so on.

In this way, you’re gradually increasing your training intensity over time, which is one of the best ways to continue building muscle when your newbie gains are long since gone.

This is how the Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger program is designed (you learn all about wave loading in chapter nineteen).

Many effective periodized training plans also involve swapping out exercises.

For instance, substituting low-bar back squats for high-bar back squats, or barbell bench press for dumbbell bench press, or standing military press for seated military press.

There are several reasons this is a good idea:

1. It reduces your risk of getting a repetitive strain injury, which results from repeating the same motion until your joints cry uncle. By rotating through similar exercises, however, you can reduce your chances of developing nagging pains.

2. It makes your workouts more interesting.

You know by now that as an intermediate or advanced weightlifter, progress is slow and hard-won. You might spend six months to add only 10 pounds to a one-rep max or a few reps with your previous year’s training weights.

Periodically focusing on different exercises won’t change this—your strength and physique will still only improve in small increments—but you’ll find it’s more enjoyable to work on, let’s say, your back squat for three months and then your front squat for three months than to grind away at one or the other for six months straight.

3. It’s probably better for strength and muscle gain.

Research shows that training a muscle group with multiple exercises may be more effective for gaining muscle and strength, likely because it better stimulates every portion of the muscle fibers.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at the University of Sao Paulo found using a combination of exercises to train the leg muscles produced more hypertrophy than doing the same amount of volume with squats alone.

In this case, they found that workouts consisting of the squat, leg press, deadlift, and lunge produced significantly more strength and muscle gain than the same amount of volume of just squats, and particularly in the hamstrings, which are less involved than the quads in the squat.

The same goes for most other muscle groups: spreading your volume over several exercises is generally more beneficial than doing a bunch of one or two exercises.

The evidence is light, but it’s also supported by the fact that most successful bodybuilders and powerlifters have been doing this for decades now.

The key to effective exercise substitution is to approach it strategically, not willy-nilly, based on how you feel or what you see other people doing in the gym.

A good rule of thumb is switching only to exercises that directly train the same muscles and swapping every eight to twelve weeks. This way, you give yourself enough time to become proficient at those exercises and make progress before replacing them.

I like to take this one step further and use slightly different rep ranges for my compound and isolation exercises because, as you know, some exercises don’t play nice with certain rep ranges.

For instance, the dumbbell side raise, dip, and skull crusher are often uncomfortable and strangely difficult in sets of less than 5 or so reps, and the squat, deadlift, and military press are often uncomfortable and strangely difficult in sets of more than 10 reps.

Many people also experience joint pain when doing heavy isolation exercises like the side raises, curls, and triceps pushdowns, and significant form breakdown when doing higher-rep squats, deadlifts, and military presses.

This is why I generally recommend you use slightly higher reps for your isolation exercises and slightly lower reps for your compound exercises (more on how to do this in a moment).

So, while there’s no single “best” kind of periodization for everyone, an ideal approach for most intermediate to advanced lifters is this:

- Use weekly undulating periodization to gradually increase the intensity and decrease the volume of your workouts throughout each mesocycle.

- Gradually increase your average intensity throughout your macrocycle by increasing your training weights at the start of each new mesocycle.

- Use slightly lower reps for your compound exercises and slightly higher reps for your isolation and accessory exercises.

Summary: There’s no single “best” kind of periodization, but most people do well with a system that gradually increases workout intensity and reducing workout volume week to week, and that uses slightly different rep ranges for compound and isolation exercises.

The Easiest Way to Use Periodization to Gain Muscle and Strength

First of all, if you’re new to lifting weights, you don’t need to use a fancy periodization system.

Instead, you just need a well designed workout routine that has you add weight or reps every week and deload every 6 to 8 weeks or whenever you hit a plateau.

Something like my Bigger Leaner Stronger program for men or Thinner Leaner Stronger program for women will be perfect for you.

Eventually, however, a simple, straightforward program like BLS or TLS won’t be enough to keep making progress. For most people, this occurs sometime in their second year of proper training.

For these people, a slightly more advanced periodization system is in order, and I recommend weekly undulating periodization.

I also recommend you use two slightly different methods of periodizing your compound and isolation exercises.

There are a couple reasons for this:

- Compound exercises are responsible for most of your strength and muscle gain, so you want to give them special attention in your programming.

- You can generally train with heavier weights more comfortably on compound exercises than isolation exercises.

- Compound exercises are easier to add weight to because most involve a barbell, which you can add anywhere from 2.5 to 10 pound. Most isolation exercises involve dumbbells, however, which move up in 10-pound increments (5 pounds per dumbbell)unless you have microplates.

Now, some people only periodize their compound exercises (because they matter the most), and don’t bother periodizing their isolation work.

This isn’t a major mistake, but I think isolation exercises are worth periodizing as well because slightly better increases in strength on these exercises can still add up to significantly more muscle over time.

My philosophy is if an exercise is worth doing at all, it’s worth doing as optimally as possible, and periodization helps accomplish this.

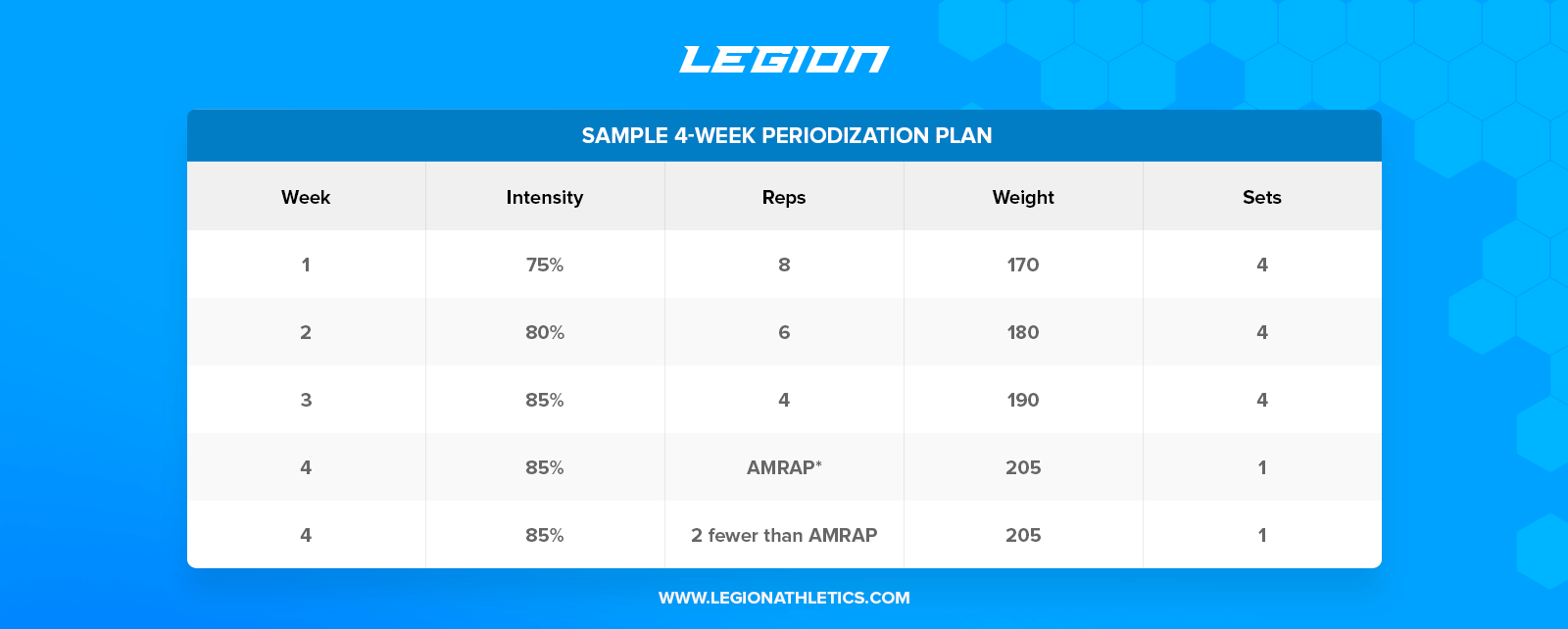

So, here’s the periodization system I recommend you use to periodize your compound exercises:

1. Each mesocycle should last 4 weeks, with the 4th week being a deload.

2. Do one to two compound exercises per workout and 3 to 4 sets per exercise.

3. Start your first week with 75% of your 1RM and do 8 reps per set.

This will have you ending each set roughly two reps shy of technical failure, which corresponds to an ~8 on an RPE scale.

4. Each week, increase the intensity by 5% and reduce each set by two reps.

For example, on week 2 you should be using 80% of your 1RM and doing 6 reps per set.

5. Continue increasing the weight and reducing the reps in this fashion for a total of 3 weeks.

6. On the 4th week, do just two sets with 85% of your 1RM.

On the first set, do what’s called an AMRAP set, which stands for “As Many Reps As Possible.”

This means you take this set to technical failure—doing as many reps as you can before your form starts to break down.

Then, on the second set, use the same weight and aim for two fewer reps than your first set (two reps shy of technical failure).

7. Use a 1RM calculator to calculate new estimated 1RMs based on how many reps you got on your AMRAP sets.

For instance, if you started a mesocycle with a 225-pound 1RM on the bench press and then got 8 reps with 190 pounds on your AMRAP set, your new 1RM would be 235 pounds.

8. Calculate your working weights for your next mesocycle based on your new estimated 1RMs.

Continuing with the above example, your new bench press 1RM of 235 pounds would mean you’d start your mesocycle with 175 pounds on the bar (75% of 235 is 176, and I like to round to the nearest 5-pound increment).

Let’s say, however, that you only got 6 reps with 190 pounds on your AMRAP set, putting your new estimated 1RM at 220 pounds. In this case, you’d start your next mesocycle with 165 pounds on the bar.

And here’s a quick illustration of this approach to periodization for someone whose estimated bench press 1RM is 225 pounds:

Now, for periodizing your isolation exercises, here’s the system I recommend:

1. Do two to three isolation exercises per workout and three to four sets per exercise.

2. At the beginning of each mesocycle (week 1), pick a weight you can do 10 to 12 reps with, while staying 1 to 2 reps shy of technical failure.

3. Try to add weight or reps every week using double progression.

That is, work with a given weight to gain reps and once you hit the top of your prescribed rep range, bump up the weight. Rinse and repeat.

4. On week four, do two sets per exercise.

For these sets, stick with your 10-to-12-rep weights and take your first set to technical failure and your second set to two reps shy of technical failure.

5. In the next mesocycle, reduce the high and low ends of your rep range by two reps.

In other words, aim for 8 to 10 reps per set for all of your isolation exercises in your next mesocycle.

6. On week eight, do two sets per exercise.

For these sets, stick with your 8-to-10-rep weights and take your first set to technical failure and your second set to two reps shy of technical failure.

7. In the next mesocycle, reduce the high and low ends of your rep range by two reps (to 6 to 8 reps per set).

8. On week twelve, do two sets per exercise.

For these sets, stick with your 6-to-8-rep weights and take your first set to technical failure and your second set to two reps shy of technical failure.

And then the entire cycle repeats anew.

You go back to doing 10 to 12 reps per set for your isolation exercises with weights that keep you 1 to 2 reps shy of technical failure, and these weights should be getting slightly heavier over time.

Here’s how this might look with dumbbell side raises over the course of a couple macrocycles:

Mesocycle 1

35 x 10 to 12 reps

Mesocycle 2

40 x 8 to 10 reps

Mesocycle 3

45 x 6 to 8 reps

Mesocycle 4

40 x 10 to 12 reps

Mesocycle 5

45 x 8 to 10 reps

Mesocycle 6

50 x 6 to 8 reps

Mesocycle 7

45 x 10 to 12 reps

Mesocycle 8

45 x 8 to 10 reps

In this way, you’re still progressing in weight on all of your isolation exercises over time, but at a slower pace than your compound exercises.

(And in case you’re wondering why mesocycle #8 is starting with the same weight as #5, it’s to illustrate that you won’t necessarily be able to increase the weight on every exercise every macrocycle).

A couple other notes on how to make this periodization system work better for you:

1. Feel free to swap exercises every 8 weeks.

You don’t need to change your exercises if you’re making good progress, but it’s a good idea if you’re getting bored, your joints are starting to complain, or you’ve hit a plateau.

I recommend you stick with exercises similar to those used in your previous mesocycle, though. For example, you could do front squats instead of back squats or high-bar squats instead of low-bar squats, and instead of barbell curls, you could do dumbbell curls.

2. Lower your estimated 1RM(s) if you’re consistently missing reps.

If you find yourself regularly failing to hit your prescribed number of reps in your workouts, reduce the estimated 1RM for the exercises you’re struggling with by 5%.

For example, if you get four reps on week two when you should get six, and it’s not due to something obvious like a bad night’s sleep, undereating, or a particularly stressful day at work, reduce your estimated 1RM by 5%.

This will usually be enough to put your reps back where they should be, but if it’s not, feel free to shave another 5% off your estimated 1RM.

Unless you’re cutting, if you need to reduce your estimated 1RM by more than 10% in the middle of a mesocycle, chances are good you either overestimated your 1RM or are making other mistakes such as undereating, undersleeping, or overtraining (usually through additional activities outside of the gym).

If you are cutting, however, you may need to reduce your 1RMs several times as you lose more and more fat, as a calorie deficit significantly impairs muscle and strength gain and post-workout recovery.

The Bottom Line on Periodization

Periodization is a method of organizing your training that involves emphasizing different aspects of your fitness at different times.

The main reason people periodize their training programs is it allows you to effectively balance stress and recovery. You gradually push yourself closer and closer to your limits before backing off and giving yourself time to recover and grow.

In this way, periodization can help you gain muscle and strength faster.

The “best” kind of periodization for you depends mostly on how experienced of a weightlifter you are.

If you’re new to lifting weights, a simple linear periodization system is all you need to optimize strength and muscle gain.

One practical way to do this is working with a handful of good exercises and trying to add weight or reps to the bar (or dumbbell) every week for several weeks, followed by a deload.

This style of periodization is what you’ll find in my Bigger Leaner Stronger program for men and Thinner Leaner Stronger program for women, and it typically works gangbusters for the first year or two.

Eventually, however, it’s worth exploring more advanced periodization strategies like weekly undulating periodization and wave loading.

When used properly, these two methods can produce significantly better results than standard linear periodization for intermediate and advanced weightlifters and be just as effective as more complex styles of periodization.

In fact, with the plan I’ve given you in this article, you should be able to keep getting bigger and stronger for the many years to come.

***

This article is from the second edition of my bestselling fitness book for experienced weightlifters, Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger, which is now live everywhere you can buy books online. Click here to learn more.

What do you think of periodization? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. In Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Vol. 11, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Bryanton, M. A., Carey, J. P., Kennedy, M. D., & Chiu, L. Z. F. (2015). Quadriceps effort during squat exercise depends on hip extensor muscle strategy. Sports Biomechanics, 14(1), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2015.1024716

- Fonseca, R. M., Roschel, H., Tricoli, V., De Souza, E. O., Wilson, J. M., Laurentino, G. C., Aihara, A. Y., De Souzaleão, A. R., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2014). Changes in exercises are more effective than in loading schemes to improve muscle strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(11), 3085–3092. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000539

- Prestes, J., Frollini, A. B., de Lima, C., Donatto, F. F., Foschini, D., de Cássia Marqueti, R., Figueira, A., & Fleck, S. J. (2009). Comparison between linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training to increase strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research / National Strength & Conditioning Association, 23(9), 2437–2442. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c03548

- Kiely, J. (2018). Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0823-y

- Afonso, J., Nikolaidis, P. T., Sousa, P., & Mesquita, I. (2017). Is empirical research on periodization trustworthy? A comprehensive review of conceptual and methodological issues. In Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (Vol. 16, Issue 1, pp. 27–34). Journal of Sport Science and Medicine. http://www.jssm.org

- Kiely, J. (2012). Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: Evidence-led or tradition-driven? In International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance (Vol. 7, Issue 3, pp. 242–250). Human Kinetics Publishers Inc. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242

- Kiely, J. (2018). Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0823-y

- Williams, T. D., Tolusso, D. V., Fedewa, M. V., & Esco, M. R. (2017). Comparison of Periodized and Non-Periodized Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 47, Issue 10, pp. 2083–2100). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0734-y

- Pugliese, L., Porcelli, S., Bonato, M., Pavei, G., La Torre, A., Maggioni, M. A., Bellistri, G., & Marzorati, M. (2015). Effects of manipulating volume and intensity training in masters swimmers. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 10(7), 907–912. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2014-0171

- Lorenz, D., & Morrison, S. (2015). CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIODIZATION OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR THE SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPIST. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 10(6), 734–747. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26618056

- Jackson, M. (2014). Evaluating the Role of Hans Selye in the Modern History of Stress. In Stress, Shock, and Adaptation in the Twentieth Century. University of Rochester Press. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26962615

- Kiely, J. (2018). Periodization Theory: Confronting an Inconvenient Truth. Sports Medicine, 48(4), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0823-y

- Bernards, J., Blaisdell, R., Light, T. J., & Stone, M. H. (2017). Prescribing an annual plan for the competitive surf athlete: Optimal methods and barriers to implementation. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 39(6), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000335

- Manchado, C., Cortell-Tormo, J. M., & Tortosa-Martínez, J. (2018). Effects of two different training periodization models on physical and physiological aspects of elite female team handball players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(1), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002259

- Kim, K.-J., Chung, J.-W., Song, H.-S., Lim, S.-T., & Min, S.-K. (2016). Effects of Long Term Periodization Training in Korean Male Elite Golfers. Journal of The Korean Society of Living Environmental System, 23(2), 243. https://doi.org/10.21086/ksles.2016.04.23.2.243

- Mallo, J. (2012). Effect of block periodization on physical fitness during a competitive soccer season. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 12(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2012.11868583

- Hoffman, J. R., Ratamess, N. A., Klatt, M., Faigenbaum, A. D., Ross, R. E., Tranchina, N. M., Mccurley, R. C., Kang, J., & Kraemer, W. J. (2009). Comparison between different off-season resistance training programs in division III American college football players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181876a78

- Pliauga, V., Lukonaitiene, I., Kamandulis, S., Skurvydas, A., Sakalauskas, R., Scanlan, A. T., Stanislovaitiene, J., & Conte, D. (2018). The effect of block and traditional periodization training models on jump and sprint performance in collegiate basketball players. Biology of Sport, 35(4), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2018.78058

- Hellard, P., Avalos-Fernandes, M., Lefort, G., Pla, R., Mujika, I., Toussaint, J. F., & Pyne, D. B. (2019). Elite swimmers’ training patterns in the 25 weeks prior to their season’s best performances: Insights into periodization from a 20-years cohort. Frontiers in Physiology, 10(APR). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00363

- Kenneally, M., Casado, A., & Santos-Concejero, J. (2018). The effect of periodization and training intensity distribution on middle-and long-distance running performance: A systematic review. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 13(9), 1114–1121. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2017-0327

- Rønnestad, B. R., Ellefsen, S., Nygaard, H., Zacharoff, E. E., Vikmoen, O., Hansen, J., & Hallén, J. (2014). Effects of 12 weeks of block periodization on performance and performance indices in well-trained cyclists. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 24(2), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12016

- Lacordia, R., Godoy, E., Vale, R., Sposito-Araujo, C., & Dantas, E. (2011). Periodized training programme and technical performance of age-group gymnasts. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 6(3), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.3.387

- Zourdos, M. C., Jo, E., Khamoui, A. V., Lee, S. R., Park, B. S., Ormsbee, M. J., Panton, L. B., Contreras, R. J., & Kim, J. S. (2016). Modified daily undulating periodization model produces greater performance than a traditional configuration in powerlifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(3), 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001165

- Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. (2009). In Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (Vol. 41, Issue 3, pp. 687–708). https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

- Kiely, J. (2012). Periodization paradigms in the 21st century: Evidence-led or tradition-driven? In International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance (Vol. 7, Issue 3, pp. 242–250). Human Kinetics Publishers Inc. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.7.3.242