Key Takeaways

- If you take a week or two away from the gym, you probably won’t lose strength or muscle mass.

- If you take more than three weeks off, you’ll lose at least a little bit of strength and muscle, but you’ll regain it quickly when you start lifting again.

- You can maintain your strength and muscle mass by lifting weights at least once per week.

When you first got into fitness, everything you read and everyone you spoke to said consistency is king.

The more you put into your workout routine, the more you get out of it. There are no shortcuts or free lunches. You learn, you hustle, and hustle, and hustle, until…finally…you get the body you want.

Don’t have time? You just don’t want it enough.

Don’t feel like going to the gym? Same thing–suck it up.

Don’t want to lift heavy? Have fun staying small.

And, no stranger to hard work, you meet the challenge every step of the way. You give 110% to your training. Every day…week…month…and year.

So far, things have gone as you envisioned. You’re bigger, leaner, and stronger than you’ve been in a while, and you don’t want the party to end.

But, what if it does have to end, at least for a little while?

What happens if you have to take a few days, a week, or even a month away from the gym?

You’ve always heard that, “If you don’t use it, you lose it,” and the second you stop lifting weights, your muscles enter a slow, steady state of decay. The longer you spend out of the gym, the smaller, weaker, and softer you’ll be at the end of your hiatus.

How true is that idea, though?

After months or years of lifting weights, do your muscles really shrink that quickly?

Well, the long story short is that yes, if you take a long enough break from lifting weights, you will lose muscle and strength. The good news, though, is that it takes much longer than most people realize, and you’ll rebuild muscle much faster than it took to gain it in the first place.

In this article, you’ll learn how long it really takes to lose muscle and strength when you stop lifting weights, what you can do to maintain your progress when you take time off, and what to expect when you get back in the swing of things.

Let’s jump right in.

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

How Fast Will You Lose Muscle If You Stop Working Out?

To understand what happens to your muscles when you stop training, we need to look at how your body responds to physical stressors on the whole.

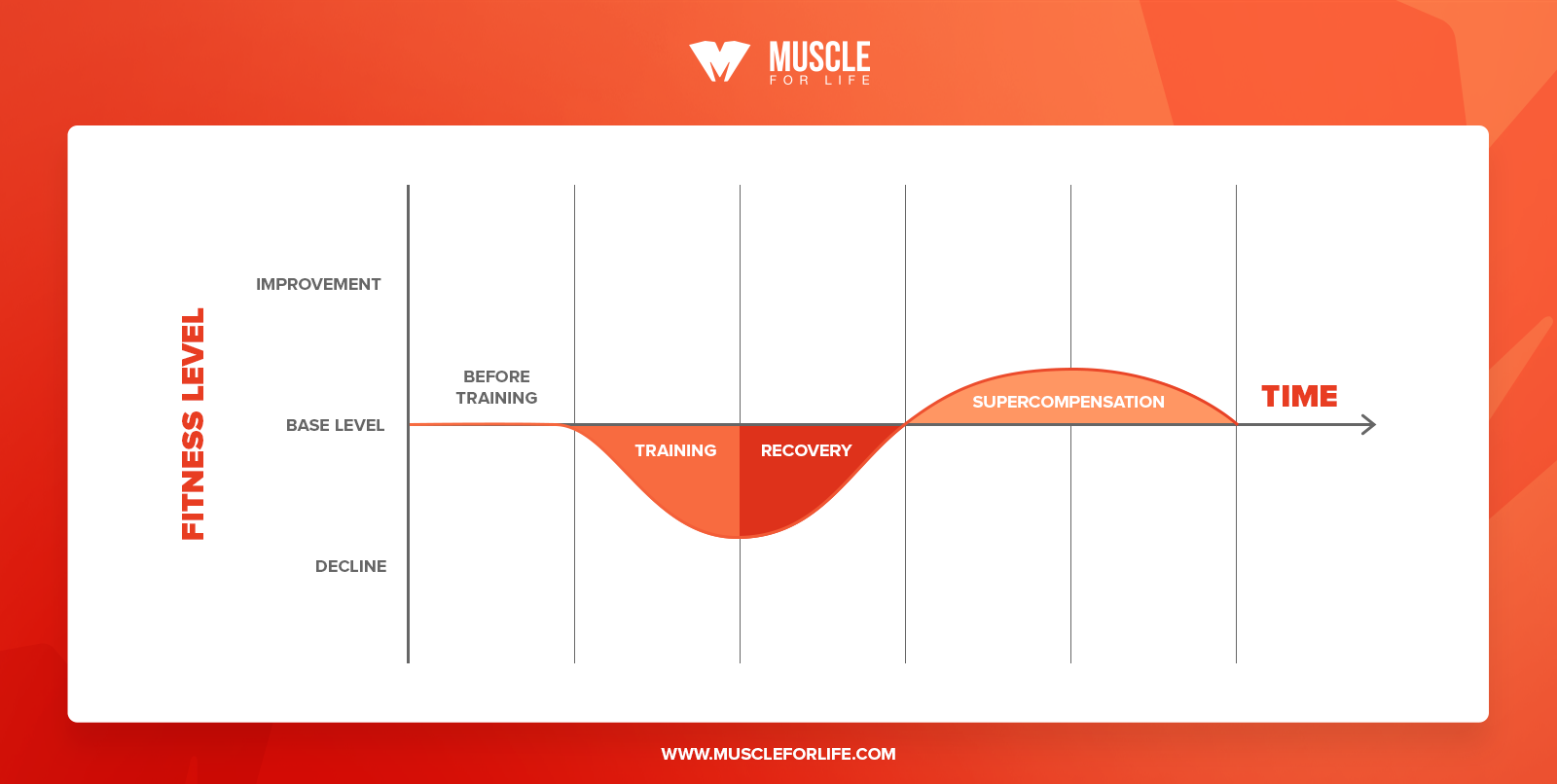

The basic theory of adaptation goes like this:

- Provide a stimulus (lift weights).

- Remove the stimulus (allow for rest and recovery).

- Adapt to deal with the next stimulus better (gain muscle and strength).

This cycle is what allows you to build muscle, get stronger, increase speed, agility, endurance, technique, and so forth. (This process is a bit of an oversimplification, but it’s more or less what’s going on).

Here’s how it looks visually:

As long as you keep providing an adequate stimulus, followed by enough recovery, then you’ll keep getting bigger, stronger, faster, and fitter.

In regards to weightlifting, this really boils down to the concept of progressive overload.

Progressive overload refers to the process whereby you gradually increase the stimulus over time to match your body’s new, higher level of ability. On the flip side, if you keep using the same weight week-after-week, it will cease to be an effective stimulus.

Now, there are multiple ways to practice progressive overload. You can do more reps, sets, exercises, or a combination of all three, but the single most effective method is to add weight to your compound exercises over time.

In short, you need to get as strong as possible on the key lifts like the squat, bench press, deadlift, and overhead press.

This will produce the highest levels of tension in the muscles, which is the strongest stimulus for muscle hypertrophy.

So, the long and short of building muscle is to hit the weights hard and heavy, allow yourself to recover, rinse and repeat.

Obviously, this doesn’t go on forever, though.

There’s a point where the demands of your workouts will outpace your body’s ability to repair itself, which is where a deload can come in handy. After getting some R&R though, you’ll keep making progress.

Now, what happens if you follow the opposite path? Instead of gradually increasing the stimulus with progressive overload, you take an extended break from training. What happens if you completely remove the stimulus for several weeks or months?

I mean…we know what happens in our heads–we wither away until, after a few weeks, we look like we don’t even lift–but what happens physiologically?

Well, not as much as you’ve probably been led to believe.

Building muscle is a slow, costly process, and once gained your body doesn’t let it disappear so easily.

Most studies show that muscle loss doesn’t begin until after two or three weeks of complete detraining. That is, no weightlifting or formal exercise of any kind.

That’s a far cry from the idea that you start to lose muscle after a matter of days.

What’s more, these studies may have overestimated muscle loss because of the tools they used to measure body composition.

Typically, scientists only measure total lean body mass (LBM), that is, everything in your body that isn’t fat. If your LBM goes down, then it’s generally assumed that you’ve lost muscle.

Muscle isn’t the only thing that contributes to your lean body mass, though.

Glycogen, a kind of carbohydrate, is largely stored in muscle and contributes to its overall size. Every gram of glycogen is stored with an additional three to four grams of water, and together, the added glycogen and water can increase muscle volume by about 16%.

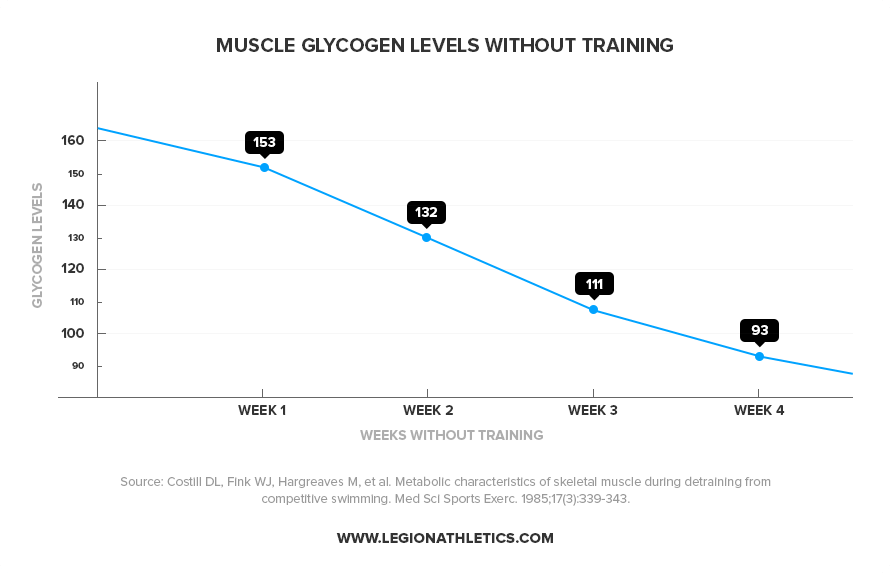

When you stop training, one of the first things that happens is there’s a drop in muscle glycogen levels.

After only one week of detraining, your muscle glycogen levels can drop by 20%, and after four weeks your glycogen levels are close to half of what they normally are.

Here’s what this looks like:

This drop in water and glycogen can cause muscle volume to shrink about 10 percent over the course of a month. This loss of lean mass returns quickly when people start lifting weights and eating more carbs.

So, even though studies have shown lean mass starts to disappear after about two or three weeks, it may take slightly longer for you to lose actual muscle.

Take four, five, or six weeks off, though, and your chances of muscle loss increase dramatically.

The good news is that when you start lifting weights again, you can expect to gain size and strength faster than you did the first time around.

This isn’t just gym lore, either, it’s a scientifically verified phenomenon known as “muscle memory.”

The answer to this enigma begins with an interesting fact about muscle cells themselves: they’re much larger than most other cells, and one of the few multinuclear cells in the body. That is, they don’t contain just one nucleus but many.

As you overload your muscles with resistance training, new nuclei are added to the muscle cells, which then allows them to grow larger. In fact, the number of nuclei within the muscle fibers is one of the most important factors that regulates muscle size.

It turns out that while an extended break from the gym clearly results in smaller, weaker muscles, the new nuclei added during the training period are retained for at least 3 months of inactivity. Some evidence shows that these new nuclei are never lost, meaning that strength training permanently alters the physiology of muscle fibers.

This was demonstrated in a 2013 study from researchers at the University of Tokyo.

The researchers had two groups of people lift weights for a total of 24 weeks. One group trained continuously throughout the whole study. The other group trained for six weeks, took three weeks off, trained for another 6 weeks, took another 3 weeks off, and then finished with 6 solid weeks of training.

The result?

Both groups gained the same amount of muscle by the end of the study.

Now, it’s likely that if the latter group kept this up for months and years, they’d gradually fall behind, but it does indicate a few extended breaks from weightlifting aren’t going to completely ruin your progress.

So all things considered, here’s what we can say:

You can safely take a week or two break from lifting weights without losing muscle mass.

After three weeks, you may lose some muscle, but not enough to notice any difference in your appearance.

At the 4-week mark, chances are good that you’ll gradually lose muscle until you start lifting weights again. Once you start working out, though, you’ll likely regain muscle faster than when you first started training.

This assumes, though, that you aren’t taking breaks like this every few months. If you spend a quarter of the year out of of the gym, you aren’t going to make the same kind of progress as someone who only takes one extended break per year from the gym.

This is also assuming that you’re eating enough calories and protein. Your energy balance and macronutrient intake can have a significant impact on your ability to maintain muscle mass, and if you’re in a calorie deficit and not eating enough protein, you will lose muscle.

How Fast Will You Lose Strength?

If you’ve ever taken a week off from training before, then you’ve probably noticed that your first few workouts back are awkward.

You can’t seem to get the movement right, the weights are more wobbly than usual, and you just feel weaker.

So, it stands to reason that you are weaker, right?

Not necessarily.

One of the largest and most extensive reviews on this topic found that experienced weightlifters can maintain their strength after a three week break from lifting. It took a full five or six weeks for their strength to decline.

This timeline also holds true for beginners. People new to weightlifting can take three weeks away from the gym without losing strength. There’s even some evidence that beginners can maintain the strength gains from a single week of training after two weeks off.

So, why do you feel so ungainly after a few days away from the gym?

Well, pure strength (your ability to recruit muscles as hard as possible, in the right order), is only part of what goes into moving heavy weights.

Your technique is more fickle. After a week or two away from the gym, you may need a few workouts to remember the little nuances of your form, like where you put your hands when you squat, how you setup during bench press, how you position your feet during military press, and so forth.

For example, if you start unconsciously using a different stance when you deadlift after a few weeks away from the gym, you’ll probably feel weaker for a workout or two. After you shake off the rust with a few workouts, you’ll be back to hitting your previous numbers.

A good rule of thumb is that you can maintain your strength for 2 or 3 weeks, but after that you’ll slowly get weaker. When you start lifting again, though, you’ll probably gain strength faster than you did when you first started lifting (for the reasons given earlier).

How to Maintain Your Muscle and Strength

So, you’re going to have to take a few weeks away from the gym, and you want to hold onto whatever gains you can.

As you now know, you could take a few weeks completely off without any major consequences.

If you’re willing to put in just a modicum of effort, though, then you can maintain your muscle and strength for several months without a problem.

This process isn’t nearly as hard as you might think.

There are just three steps:

- Eat enough to maintain your weight.

- Eat enough protein.

- Stay active.

1. Eat enough to maintain your weight.

Your body’s ability to build and maintain muscle is strongly affected by how much you eat.

You see, you feed your body so much energy every day and it burns so much through activity. The relationship between these quantities is known as energy balance.

If you eat more calories than you burn, you’re going to be in a calorie surplus. This is helpful when you want to build muscle, but it also results in fat gain.

If you burn more calories than you consume, you’re going to be in a calorie deficit. This is necessary for losing fat, but it also impairs your ability to synthesize muscle proteins and reduces anabolic and increases catabolic hormone levels.

The net result is that when you eat less, your body just can’t rebuild and grow muscle tissue as effectively.

That’s the price of admission for losing body fat, but it’s not what you want if you’re taking several weeks off from training.

One of the strongest stimuli for muscle growth is strength training, which is why you can lose fat and build muscle while dieting if you also lift weights. Take away that stimulus, though, and you’ll increase your chances of muscle loss if in a calorie deficit.

So, if you have to take a few weeks away from the gym you’ll maintain more muscle if you eat enough calories every day to maintain your weight. This is known as your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE).

To find your TDEE, check out this article:

2. Eat enough protein.

Second to eating enough calories, your next highest priority is eating enough protein every day.

Both calorie restriction and weightlifting increase your body’s requirement for dietary protein, which is why you’ll typically maintain more muscle while dieting if you eat at least a gram of protein per pound of body weight.

Now, since you’re going to be eating your TDEE and abstaining from the gym, you don’t need to eat as much protein as you would while bulking or cutting.

In this case, you can maintain your muscle mass by eating around 0.6 to 0.8 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day. Other research indicates higher intakes might be better, though, and the costs of eating slightly too much protein are less than eating too little.

Another benefit of eating more protein is that it’s more satiating than carbs or fat. If you tend to overeat when you stop lifting, this may help keep your appetite in check.

So, a good rule of thumb is to eat 0.8 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight per day while taking time off from the gym.

You could probably get away with eating slightly less than that, but that’s a good starting place for most.

If you want to learn exactly how much protein you should eat to improve your body composition, check this out:

3. Stay active.

Strength training isn’t the only kind of exercise that can maintain muscle mass.

In fact, daily activities like walking, washing dishes, carrying groceries, and the like provide more of a muscle building stimulus than most realize.

If you stop lifting weights but maintain your daily activity levels, you can hold onto muscle reasonably well.

What happens if you completely veg out, though?

Well, one of the fastest and most reliable ways to lose muscle is to move as little as possible. In cases where people are completely immobilized, they can lose 5 to 10 percent of their muscle mass in two weeks.

All those small daily movements add up to a decent muscle building stimulus, and when you remove that stimulus, the result is rapid muscle loss.

Now, even if you make an effort to be as slothful as possible, you probably won’t lose that much muscle. Even walking from the couch to your fridge will provide a small stimulus for muscle growth.

At bottom, though, the more active you are the better you’ll maintain muscle mass during your break.

And if you’re going to take off more than four weeks from the gym, it’s worth making an effort to do at least one structured workout per week.

That’s enough to hold onto your gains for eight weeks before things start to go downhill, or with about a third of the volume that it takes to build muscle.

So, if you need to take more than a month or two off, try to lift weights at least once a week.

The Bottom Line on How Long it Takes to Lose Muscle

Contrary to what you may have heard, you won’t lose muscle or strength if you take a week or two off from the gym.

It takes a while to build muscle, and it doesn’t just disappear the second you stop lifting.

Take more than three weeks off, though, and you will probably lose some strength and muscle.

The good news is that once you start lifting again, you’ll gain muscle in less time than it took to build it in the first place.

The single most common mistake people make when they stop lifting weights is to completely let go of the reigns–they stop doing any kind of exercise, eat whatever they please, and generally become as indolent as possible.

Don’t do that.

Instead, maintain your hard work with these three steps:

- Eat enough to maintain your weight.

- Eat enough protein.

- Stay active (and lift weights at least once a week if you take more than a month off).

Do that, and you should have no trouble maintaining your strength and muscle mass.

What’s your take on losing muscle from not working out? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Helms ER, Aragon AA, Fitschen PJ. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11(1):20. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Bickel CS, Cross JM, Bamman MM. Exercise dosing to retain resistance training adaptations in young and older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1177-1187. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318207c15d

- Tavares LD, de Souza EO, Ugrinowitsch C, et al. Effects of different strength training frequencies during reduced training period on strength and muscle cross-sectional area. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(6):665-672. doi:10.1080/17461391.2017.1298673

- Glover EI, Phillips SM, Oates BR, et al. Immobilization induces anabolic resistance in human myofibrillar protein synthesis with low and high dose amino acid infusion. J Physiol. 2008;586(24):6049-6061. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160333

- Jones SW, Hill RJ, Krasney PA, O’Conner B, Peirce N, Greenhaff PL. Disuse atrophy and exercise rehabilitation in humans profoundly affects the expression of genes associated with the regulation of skeletal muscle mass. FASEB J. 2004;18(9):1025-1027. doi:10.1096/fj.03-1228fje

- de Boer MD, Selby A, Atherton P, et al. The temporal responses of protein synthesis, gene expression and cell signalling in human quadriceps muscle and patellar tendon to disuse. J Physiol. 2007;585(1):241-251. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142828

- Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety. In: American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Vol 87. ; 2008. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1558s

- Phillips SM, van Loon LJC. Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to optimum adaptation. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(SUPPL. 1). doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.619204

- Phillips SM. Dietary protein requirements and adaptive advantages in athletes. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(SUPPL. 2). doi:10.1017/S0007114512002516

- Demling RH, DeSanti L. Effect of a hypocaloric diet, increased protein intake and resistance training on lean mass gains and fat mass loss in overweight police officers. Ann Nutr Metab. 2000;44(1):21-29. doi:10.1159/000012817

- Tomiyama AJ, Mann T, Vinas D, Hunger JM, Dejager J, Taylor SE. Low calorie dieting increases cortisol. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(4):357-364. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d9523c

- Cangemi R, Friedmann AJ, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Long-term effects of calorie restriction on serum sex-hormone concentrations in men. Aging Cell. 2010;9(2):236-242. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00553.x

- Zito CI, Qin H, Blenis J, Bennett AM. SHP-2 regulates cell growth by controlling the mTOR/S6 kinase 1 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(10):6946-6953. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608338200

- Costa P, Herda T, Herda A, Cramer J. Effects of Short-Term Dynamic Constant External Resistance Training and Subsequent Detraining on Strength of the Trained and Untrained Limbs: A Randomized Trial. Sports. 2016;4(1):7. doi:10.3390/sports4010007

- Hakkinen K, Alen M, Kallinen M, Newton RU, Kraemer WJ. Neuromuscular adaptation during prolonged strength training, detraining and re-strength-training in middle-aged and elderly people. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;83(1):51-62. doi:10.1007/s004210000248

- Hwang PS, Andre TL, McKinley-Barnard SK, et al. Resistance Training–Induced Elevations in Muscular Strength in Trained Men Are Maintained After 2 Weeks of Detraining and Not Differentially Affected by Whey Protein Supplementation. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(4):869-881. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001807

- McMaster DT, Gill N, Cronin J, McGuigan M. The development, retention and decay rates of strength and power in elite rugby union, rugby league and american football: A systematic review. Sport Med. 2013;43(5):367-384. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0031-3

- Ogasawara R, Yasuda T, Ishii N, Abe T. Comparison of muscle hypertrophy following 6-month of continuous and periodic strength training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113(4):975-985. doi:10.1007/s00421-012-2511-9

- Gundersen K, Bruusgaard JC. Nuclear domains during muscle atrophy: Nuclei lost or paradigm lost? J Physiol. 2008;586(11):2675-2681. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154369

- Gundersen K. Excitation-transcription coupling in skeletal muscle: The molecular pathways of exercise. Biol Rev. 2011;86(3):564-600. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00161.x

- Bruusgaard JC, Johansen IB, Egner IM, Rana ZA, Gundersen K. Myonuclei acquired by overload exercise precede hypertrophy and are not lost on detraining. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(34):15111-15116. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913935107

- Bruusgaard JC, Liestøl K, Ekmark M, Kollstad K, Gundersen K. Number and spatial distribution of nuclei in the muscle fibres of normal mice studied in vivo. J Physiol. 2003;551(2):467-478. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045328

- Staron RS, Leonardi MJ, Karapondo L, et al. Strength and skeletal muscle adaptations in heavy-resistance-trained women after detraining and retraining. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70(2):631-640. doi:10.1152/jappl.1991.70.2.631

- Kalapotharakos VI, Smilios I, Parlavatzas A, Tokmakidis SP. The effect of moderate resistance strength training and detraining on muscle strength and power in older men. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2007;30(3):109-113. doi:10.1519/00139143-200712000-00005

- Coratella G, Schena F. Eccentric resistance training increases and retains maximal strength, muscle endurance, and hypertrophy in trained men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(11):1184-1189. doi:10.1139/apnm-2016-0321

- Costill DL, Fink WJ, Hargreaves M, King DS, Thomas R, Fielding R. Metabolic characteristics of skeletal muscle during detraining from competitive swimming. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1985;17(3):339-343. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3160908. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Cardiorespiratory and metabolic characteristics of detraining in humans. In: Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. Vol 33. American College of Sports Medicine; 2001:413-421. doi:10.1097/00005768-200103000-00013

- Hansen BF, Asp S, Kim B, Richter EA. Glycogen concentration in human skeletal muscle: effect of prolonged insulin and glucose infusion. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;9(4):209-213. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999.tb00235.x

- Nygren AT, Karlsson M, Norman B, Kaijser L. Effect of glycogen loading on skeletal muscle cross-sectional area and T2 relaxation time. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173(4):385-390. doi:10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00913.x

- Dirks ML, Wall BT, Van De Valk B, et al. One week of bed rest leads to substantial muscle atrophy and induces whole-body insulin resistance in the absence of skeletal muscle lipid accumulation. Diabetes. 2016;65(10):2862-2875. doi:10.2337/db15-1661

- Jespersen JG, Nedergaard A, Andersen LL, Schjerling P, Andersen JL. Myostatin expression during human muscle hypertrophy and subsequent atrophy: Increased myostatin with detraining. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2011;21(2):215-223. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01044.x

- McMahon GE, Morse CI, Burden A, Winwood K, Onambélé GL. Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(1):245-255. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318297143a

- Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(10):2857-2872. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

- Kiely J. New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization: Block periodization: New horizon or a false dawn? Sport Med. 2010;40(9):803-805. doi:10.2165/11535130-000000000-00000