Key Takeaways

- Heavy drinking is closely linked with a number of health problems including cancer, liver disease, heart failure, and a shortened lifespan.

- At the other extreme, several new studies seem to show even moderate drinking—1 to 2 drinks per day—may shorten your life and increase your risk of disease.

- Keep reading to learn what the scientific literature actually says about how much it’s safe to drink.

There’s no doubt heavy drinking is a ticket to an early death.

The CDC estimates 88,000 Americans die annually from alcohol-related causes, which includes car accidents, a cornucopia of cancers, and liver disease.

Fifteen million Americans are believed to have an alcohol dependency disorder, and until recently alcohol killed more people than opioids.

That’s not to mention the disastrous effects of alcoholism on quality of life, mental health, productivity, and relationships.

Of course, you’ve heard all this before, and don’t need me to tell you heavy drinking can ruin and shorten your life.

That said, you’ve also probably heard that moderate drinking is good for you. That’s the claim doctors, scientists, and beverage companies have promoted for years—heavy drinking is bad for you and moderate drinking is beneficial.

Now, though, the pendulum is swinging in the other direction after a series of studies emerged that seemed to show alcohol is dangerous in any amount.

For example, CNN published an article titled “Even one drink a day could be shortening your life,” in reference to one such study (which you’ll learn about in a moment).

Suddenly, the fashionable opinion is that any alcohol is bad for you, full stop, and even moderate drinking is an invitation to long-term health problems.

Is this true, though?

Are you shortening your life by having a glass or two of wine or beer each night?

Well, the simple answer is no, probably not.

The more complicated answer is that there’s still a lot we don’t know about the long-term effects of alcohol and there’s no one size fits all answer for how much alcohol you can safely drink.

So, what exactly does alcohol do to your body, and how much can you safely drink?

Keep reading to learn the answer.

What Happens to Your Body When You Drink Alcohol

Alcohol, also known as ethanol, is a chemical produced by the fermentation of grains, fruits, and other carbohydrate-containing foods.

When ingested, it has drug-like properties and serves as a source of calories.

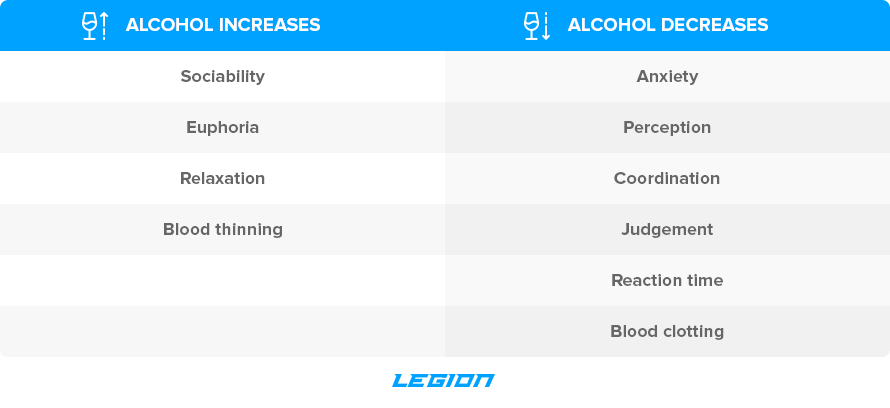

The most obvious and immediate effects of alcohol are psychological. Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant, and in low to moderate amounts it reduces anxiety, increases sociability, and causes feelings of mild euphoria. In higher amounts it can impair perception and judgement, slow reaction time, and lead to stupor, unconsciousness, and eventually death.

Aside from being a powerful drug, alcohol is also used as a source of energy (calories) by the body, although it’s processed quite differently than carbs, fats, or protein.

When broken down in the liver, alcohol produces a toxic compound called acetaldehyde. Luckily, acetaldehyde is quickly converted into another compound called acetate, which is then converted into carbon dioxide and water.

The body is well equipped to metabolize small amounts of acetaldehyde before it can cause any damage, but it can only process so much per hour. This is why most of the negative effects of alcohol are due to frequent excessive drinking, which doesn’t leave enough time for the body to clear all the acetaldehyde from the blood before it wreaks havoc in the body.

Thus, saying “alcohol is a toxin” isn’t entirely accurate. It can be toxic in excess, but so can many other substances we consume on a regular basis.

High levels of blood glucose can also be toxic, as can sodium, potassium, and iron, which is why the body works hard to keep the blood levels of these substances in a healthy range.

Likewise, the body is easily capable of controlling blood levels of alcohol and acetaldehyde so long as you don’t drink excessively.

One side effect of digesting alcohol, though, is a decrease in fat burning throughout the body.

While the body is preoccupied breaking down alcohol and acetaldehyde, it shuts down the digestion of other nutrients while alcohol is still present in the blood. Thus, any fat or carbs you eat will be stored as body fat (in the case of dietary fat) or glycogen (in the case of carbs) until your body clears the alcohol from your blood.

So, if you’re in a calorie surplus and consuming plenty of dietary fat, alcohol can cause excess fat storage.

What if you’re eating at maintenance or in a calorie deficit, though?

In that case, alcohol has little to no impact on body fat levels.

The body has no efficient way to convert acetaldehyde to body fat, so little to no alcohol is ever converted directly into body fat. Unless you’re also eating lots of dietary fat and carbs and in a calorie surplus, alcohol isn’t going to contribute to fat gain.

There’s even some evidence small amounts of alcohol may have beneficial effects on body composition. For example, research shows people who drink moderately tend to be leaner than people who don’t drink.

There are several explanations for this.

For one, moderate alcohol consumption tends to decrease food intake over the long-term and improves insulin sensitivity.

Alcohol is also unique in that it has a high thermic effect, with about 20% of the calories in alcohol being burned during digestion.

Although you’ve probably read that alcohol contains 7 calories per gram, in reality it’s closer to 5.7 calories per gram due to this thermic effect. As a result, when people substitute some of their daily carb intake with an equivalent amount of alcohol, they often lose weight.

When it comes to muscle-building, research shows moderate alcohol consumption has little to no impact on your ability to gain muscle or strength, while consuming lots of alcohol reduces testosterone levels and probably interferes with muscle growth and recovery.

Of course, the real problems with alcohol begin when you frequently consume large amounts over long periods of time.

Chronic heavy drinking can cause a long list of problems including …

- Muscle loss

- Obesity

- Depression

- Suicidal behavior

- A variety of cancers

- And a long list of other maladies

Circling back to the topic of this article, though, what about the effects of moderate drinking?

If we’re able to control ourselves and only drink reasonable amounts of alcohol, are we still putting our health in danger?

Read on to find out.

Summary: In the short term, moderate alcohol intake has few negative health effects and possibly several positive ones, whereas heavy drinking is linked to a long list of diseases and psychological ailments.

How Does Alcohol Affect Immune Function?

There’s an old cock-and-bull-story that goes like this:

Since alcohol can kill viruses and bacteria outside the body, drinking alcohol will help kill viruses and bacteria inside the body.

What with Rona still making the rounds, and many people looking for ways to soothe their boredom and anxiety, the idea of drinking alcohol for … uh … health reasons, seems appealing.

The idea that drinking alcohol could reduce your chances of getting coronavirus was recently revived when Alexander Lukashenko, the president of Belarus, claimed that “People should not only wash their hands with vodka but also poison the virus with it… You should drink the equivalent of 40 to 50 milliliters of rectified spirit daily. But not at work,” the Times of London reports.

The World Health Organization (WHO) responded by issuing a rebuttal, but went to the other extreme and claimed that any amount of alcohol could suppress immune function.

Who’s right?

On the one hand, scientists have known for decades that heavy drinking is linked with worse immune function and a higher risk of infectious diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at Aarhus University Hospital found that people who drank heavily multiple times per week (>7 drinks per week) had a higher risk of being hospitalized with pneumonia than those who drank 0 to 6 times per week.

More or less all scientists agree that binge drinking and alcoholism can impair immune function. On the other hand, it’s not as clear what effect moderate drinking has on your immune system.

A review study conducted by researchers at the Spanish National Research Council found that moderate drinking (10 to 14 grams of alcohol per day or less for women and 20 to 24 or less for men) was associated with slightly better immune function than abstinence. That said, other controlled trials have found that moderate drinking isn’t likely to help or hurt immune function.

The takeaway?

If you already drink moderately, giving up alcohol entirely is unlikely to reduce your risk of getting sick. That said, if you have a tendency to flirt with the line between “moderate” and “excessive” drinking, now’s a good time to cut back and play it safe.

Summary: Moderate drinking probably doesn’t decrease immune function or increase your risk of getting sick, but heavy drinking does.

What Is Moderate Drinking?

Before we look at whether or not moderate drinking is bad for you, it’s important we define “moderate drinking.”

While there’s no official definition of moderate drinking, it’s usually interpreted as “more than zero and less than the maximum recommended amount.”

Most countries publish recommended ceilings for alcohol consumption, but these can be difficult to interpret unless you’re familiar with the alcohol content and normal serving sizes of different beverages. What’s more, different countries often recommend different safe ceilings for alcohol consumption.

For example, U.S. dietary guidelines recommend men have no more than two drinks per day and women have no more than one drink per day, but that’s not very helpful.

How big is one drink?

One drink of what beverage?

What if one beverage has more or less alcohol than usual?

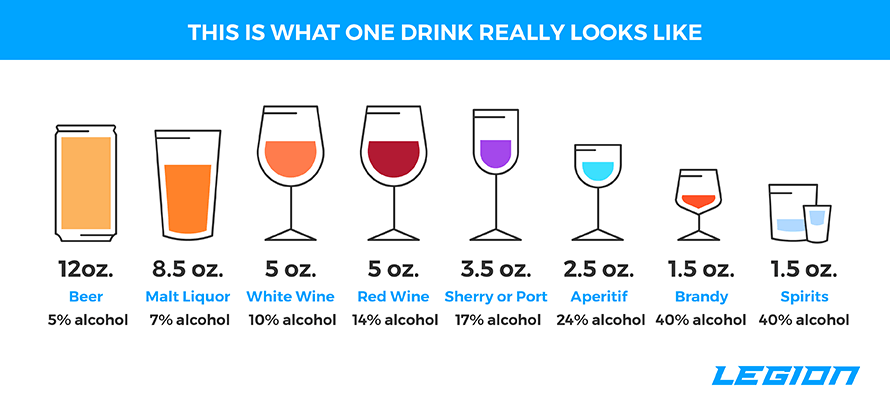

Different drinks usually come in different serving sizes, and contain different amounts of alcohol. For example, beer has less alcohol than most cocktails, but beer also comes in larger servings.

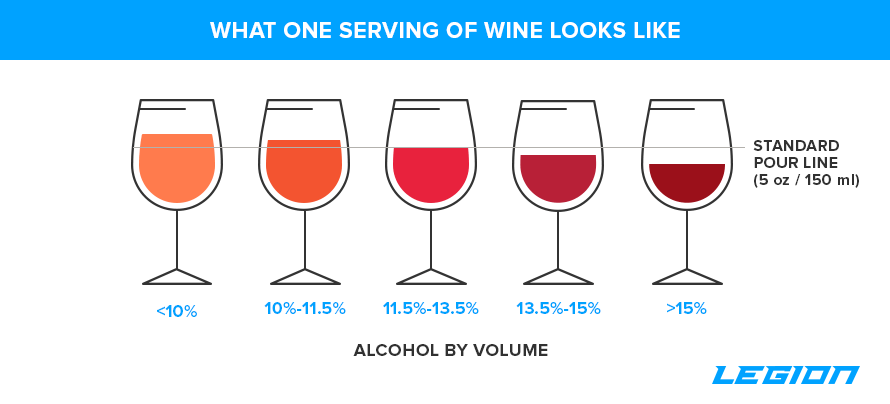

Further complicating matters, different variations of the same alcoholic beverage can also have different amounts of alcohol. For example, white wine can have as little as 5% alcohol by volume (ABV) or as much as 14%, whereas red wines can range from 12 to 18% ABV.

Here’s a chart showing how you would have to change your serving size of different kinds of wine to consume roughly 14 grams of alcohol (one serving):

Using the U.S. guidelines again, one “drink” is defined as a beverage containing 14 grams of alcohol, and it’s recommended that men consume no more than two drinks per day and women consume no more than one. Thus, “moderate drinking” in the U.S. is 28 grams per day of alcohol or less for men and 14 grams or less for women.

If you live in the U.K. the math will look a bit different. Across the pond, it’s recommended that men have no more than three drinks per day and women no more than two, and a serving of alcohol is 10 grams. Thus, “moderate drinking” in the U.K. is 30 grams or less alcohol per day for men and 20 grams or less for women.

Many other European countries like Spain, France, and Poland don’t place a limit on the number of drinks you should have, and instead put an exact ceiling on the number of grams of alcohol you should consume per day.

Spain, for example, recommends men drink no more than 40 grams of alcohol per day and women drink no more than 25. Poland has similar guidelines, although instead of a daily limit they recommend men drink no more than 280 grams of alcohol per week and women no more than 140.

As you can see, “moderate drinking” means different things depending on where you live, which makes it a pretty unhelpful guideline when deciding how much (or little) you should drink to stay healthy.

So, instead of relying on a vague and inconsistent definition like “moderate drinking,” it’s important you calculate how many grams of alcohol you consume, and then look at what research says is a safe amount to have on a regular basis (which you’ll learn in a moment).

To calculate how many grams of alcohol are in a beverage, you just need to multiply the volume of the beverage (in fluid ounces or milliliters) by the alcohol by volume (ABV).

Here’s a helpful chart with serving sizes and average ABV numbers for different alcoholic beverages:

Once you have these two numbers, you can multiply them together to see how many grams of pure alcohol you’re consuming.

For example, red wine generally contains around 12% ABV and one glass of wine is usually about 5 fluid ounces.

Here’s what the math would look like:

12% x 5 = 0.6

One fluid ounce of alcohol is about 30 grams, so . . .

0.6 x 30 = 18 grams of alcohol

If you’re using the metric system the calculation looks the same, except you don’t need to convert fluid ounces into grams.

One glass of wine is usually about 150 ml.

12% x 150 = 18 grams of alcohol

If we’re talking beer, a standard serving is 12 fluid ounces (350 ml), and most beers contain around 5% ABV.

Here’s what the calculation would look like using fluid ounces:

12 x 0.05 = 0.6

0.6 x 30 = 18 grams of alcohol

Now that you know how to quantify how much alcohol you’re really drinking, it’s time to look at how much it’s safe to drink.

Summary: There’s no consistent definition of what constitutes “moderate drinking,” although in most countries it’s about 30 to 40 grams of alcohol or less per day for men (1 to 2 servings) and about half that for women (1 serving).

Is Moderate Drinking Bad for You?

Here’s the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question:

Assuming you stick to the normal guidelines for moderate alcohol consumption—around 30 to 40 grams of alcohol or less per day for men and about half that for women—do you have anything to worry about?

Well, the research goes both ways.

On the one hand, many studies have shown moderate alcohol consumption has small health benefits or is at worst benign.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine looked at the drinking habits and longevity of 12,000 elderly men between 1978 and 1991.

They found that the risk of death was lowest among moderate drinkers—those who had about one or two drinks per day on average—and higher among non-drinkers and people who drank more than two drinks per day.

The researchers concluded that drinking “ … an average of one or two units of alcohol a day is associated with significantly lower all cause mortality than is the consumption of no alcohol, or the consumption of substantial amounts.” In this case, one unit would have been about 15 to 20 grams of alcohol, which means these people were within the normal guidelines of moderate drinking.

Other studies conducted by scientists at The American Cancer Society, Copenhagen University, and The University of Münster have all found more or less the same thing: people who have one or two drinks per day generally live longer than people who don’t drink at all or drink significantly more than this.

All of these studies suffer from major problems, though.

Most importantly, these were all observational studies, which means they can’t prove drinking was responsible for the positive health effects.

Unlike randomized controlled trials, where researchers can isolate the effects of a single behavior (like alcohol consumption), observational studies are plagued with “confounding variables”—factors that can swing the results in favor of one conclusion or the other.

Some of these befuddling variables can make moderate drinking look better than it really is, and in other cases they can make it look worse than it really is.

For example, in many of these studies the people who drank moderately were also wealthier and more educated than the people who drank the most. Since wealthier, more educated people also tend to be healthier, it’s possible the moderate drinkers lived longer in spite of their alcohol intake, not because of it.

Another strange confounding variable is known as the “sick quitter” problem.

Many people who abstain from alcohol do so because they’re dealing with a health issue or are former alcoholics, whereas healthy people are free to drinking moderately. Thus, if you compare a group of teetotalers to a group of moderate drinkers, the moderate drinkers will often look healthier on the whole.

In other words, saying that people who drink are healthier than people who don’t is like saying blind people have a lower risk of dying in a car accident. It’s not that being blind makes you a better driver, it’s that being blind prevents you from driving, thus lowering your risk of dying in a car accident.

Further complicating matters is the fact that other confounding variables can make moderate drinking look worse than it really is.

For example, in most observational studies, alcohol consumption is measured in terms of average drinks over a series of months or years. Thus, someone could binge on 10 drinks several times per month and still be counted as a “moderate drinker,” because their daily average would still work out to 1 to 2 drinks per day.

Infrequent binge drinking like this is far more likely to cause health problems than moderate daily alcohol consumption, so if enough of these people are included in a study it will make moderate drinking look worse than it really is.

There’s also the problem of misreporting. Many people are ashamed to admit they drink too much, and thus many heavy drinkers might claim to be moderate drinkers, further muddling the results.

Accounting for all of these variables is nearly impossible, but when scientists have tried, the beneficial effects of moderate drinking often dry up.

For example, one study conducted by scientists at Massey University looked at the drinking habits, health, and socioeconomic status of 3,000 elderly men (average age 65). They divided the subjects into people who didn’t drink, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers, and as usual, found moderate drinkers were the healthiest.

When they accounted for two of the biggest confounding variables, though—income and education—the health benefits of moderate drinking mostly disappeared. That is, most of the moderate drinkers were also wealthier and better educated, which probably had more to do with their superior health than their drinking habits.

On the whole, it’s probably fair to say that the health benefits of moderate alcohol consumption are overblown.

That said, is it fair to say that moderate alcohol consumption is bad for you?

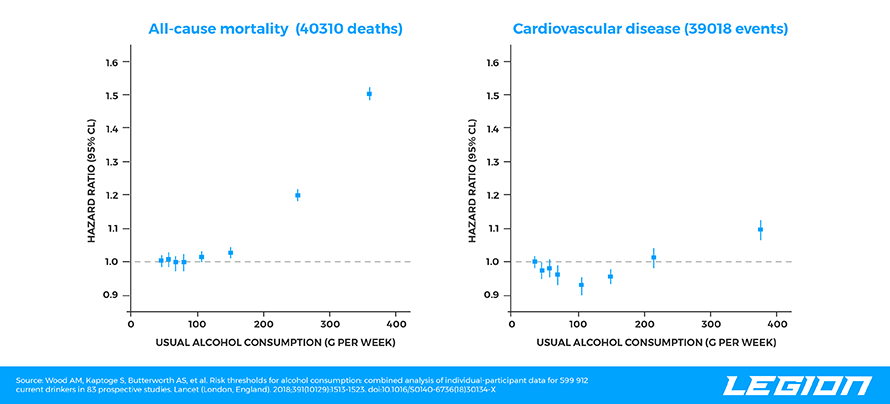

To answer that question, scientists at the University of Cambridge conducted one of the largest studies on the health effects of alcohol to date.

They looked at how alcohol intake affected the longevity and cardiovascular health of 600,000 drinkers from 83 studies in 19 countries. By only looking at drinkers, they avoided the problem of including “sick quitters” in their results.

In this case, they found that moderate drinking—less than 100 grams of alcohol per week (14 grams per day) or around seven glasses of wine or beer—had more or less no impact on longevity. When people drank more than that, though, their risk of dying increased.

Using a mathematical model, the researchers estimated that people who drank 7 to 14 drinks per week had a six-month lower life expectancy at age 40 than moderate drinkers. At the extreme end, people who drank 14 to 24 drinks per week had a 1 to 2 year lower life expectancy, and people who drank more than 24 drinks per week had a 4 to 5 year lower life expectancy at age 40.

Here’s what the results looked like:

As you can see, when people drank significantly more than 100 grams of alcohol per week, their risk of dying and of heart disease increased.

This is the study CNN touted as proving “Even one drink a day could be shortening your life.”

In reality, though, that’s not what this study showed. Instead, it showed that if you’re already having one drink per day, doubling that amount could be associated with a shorter life.

Shortly after this study came out, it was dwarfed by an even larger study that painted alcohol in an even worse light.

In this case, a team of scientists from around the world looked at how alcohol intake was related to health in millions of people from 195 countries across 700 studies.

As you’d expect, they found that heavy drinking was linked to a plethora of illnesses and an early death. The kicker, though, was that the study also seemed to show that even small amounts of alcohol intake were associated with poor health and a shorter lifespan.

As the authors bluntly concluded, “the safest level of drinking is none.”

This study gained widespread attention on the interwebs, sparked dozens of articles, and made waves in the scientific community, as it seemed to prove that even moderate drinking was dangerous.

There’s just one problem: this study didn’t prove zero drinking was better than moderate drinking.

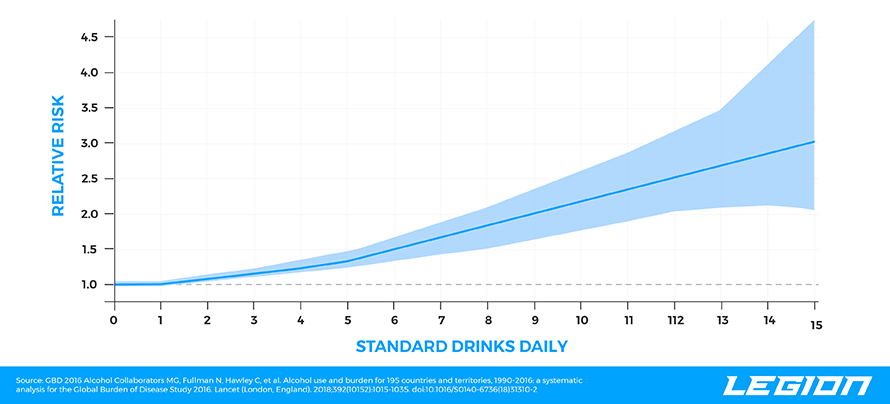

Here’s a graph from the paper showing the relationship between the risk of alcohol-related health problems and the number of drinks people consumed per day:

As you can see, the difference between zero drinks and one drink per day is almost nonexistent, and the risk doesn’t start to go up significantly until you’re downing about two drinks per day.

Here’s another example to put this kind of risk into perspective. The study found that one drink per day increased the risk of alcohol-related health problems by 0.5% compared to non-drinkers. As professor of pediatrics Aaron Carrol points out, this means if 100,000 non-drinkers started having one drink per day, four of them would run into some kind of alcohol-related health issue.

Now, you might argue this is still strong enough evidence to avoid alcohol altogether, but even here you can’t really take these results at face value.

This study, like all of the others you’ve learned about so far, was observational, which means it can’t establish cause and effect. It can help you establish associations between different variables, like alcohol intake and health problems, but the results need to be significant, repeatable, and taken with a grain of salt.

For example, almost all of the studies on cigarette smoking are observational, but the results are so overwhelmingly consistent and disastrous (for smokers) that it’s considered an incontestable fact that smoking is bad for you. We also have many studies showing tobacco smoke is bad for other mammals, so it’s safe to assume it will have similar effects on us humans.

That’s not the case with moderate drinking.

Instead, we have a few observational studies that show an almost imperceptible increase in risk from no drinking to moderate drinking, which could easily be due to confounding variables.

While the authors of this last study tried to account for various things like income and education, there are simply too many variables for researchers to control for all of them.

For instance, this study didn’t account for people’s BMI, physical activity, or smoking status, which obviously have a massive influence on longevity and health and could easily account for the paltry 0.5% increase in risk that was attributed to drinking.

While this study did show a clear correlation between heavy drinking and worse health, it didn’t prove moderate drinking is bad for you or that “the safest level of drinking is none,” as the authors claimed.

So, where does that leave us?

On the one hand, the health benefits of alcohol have probably been oversold, and nowadays most doctors and researchers recommend that if you don’t currently drink, there’s no reason to start for health reasons.

On the other hand, most research also shows that moderate drinking—about one or two drinks per day on average—is probably benign and unlikely to help or harm your health.

Summary: Most studies show drinking one or two servings of alcohol per day poses little to no risk to your health, although it’s also unlikely to offer any benefits.

How Much You Can Safely Drink

As discussed earlier, defining “moderate drinking” in terms of numbers of drinks per day is misleading.

Servings sizes vary from drink to drink, the definition of a “drink” varies from country to country, and different drinks can have vastly different amounts of alcohol.

Thus, the only objective way to measure your alcohol consumption is to look at how many grams of pure alcohol you consume. Some studies, such as this one, set a single limit of “100 grams per week” of alcohol for everyone, but this also presents a problem:

People with more body mass can safely consume more alcohol than people with less body mass and vice versa. While 40-grams of alcohol might not buzz a 300-pound man, it could completely besot a 100-pound woman.

The reason for this is that the damaging effects of alcohol occur when it reaches a certain blood alcohol concentration. If you have more body mass, you have more blood to dilute the alcohol, allowing you to consume larger amounts without suffering negative effects than people with less body mass.

Thus, it might seem like a good idea to set a daily alcohol limit based on your body weight, but this presents another problem:

Different people metabolize alcohol at very different rates depending on their genetics. Thus, a 300-pound man who metabolizes alcohol very slowly could still get drunk after just a few glasses, whereas a 100-pound woman who metabolizes alcohol quickly might only have a strong buzz after consuming the same amount.

So, where does that leave us?

Based on all of the research covered in this article and the national guidelines of most countries (which are also based on their own research), here’s a good rule of thumb for moderate drinking:

Don’t drink more than 20 to 30 grams of alcohol per day if you’re a man or more than 10 to 20 grams of alcohol per day if you’re a woman.

These guidelines differ from country to country, but most are close to these ranges.

Don’t drink more than 140 to 210 grams of total alcohol per week if you’re a man or more than 70 to 140 grams per week if you’re a woman.

Tracking your weekly alcohol consumption gives you a little more flexibility in your daily alcohol intake. For example, if you consume 40 grams of alcohol one day, you could cut back the rest of the week to make sure your average alcohol intake is still within safe limits.

That said, there’s a limit to how much you can safely “budget” your alcohol intake like this.

If you’re a man, consuming 210 grams of alcohol on Saturday and abstaining the rest of the week is still unhealthy, even though you’re technically consuming a “safe” amount of alcohol throughout the week.

Don’t get drunk more than a few times per year.

Weddings, sports games, anniversaries, holiday parties, and so forth are all tempting occasions for oiling your gullet, and many people are going to do so regardless of the long-term health risks.

If you fall into that group, just try to limit these splurges to no more than a few times per year. Most of the negative health effects of alcohol are linked to repeated binge drinking or consistently high daily alcohol intake, which leaves little to no time for your body to repair the damage.

There’s really no “safe” frequency of binge drinking, but so long as you can allow at least several months between benders you can minimize the fallout.

Aim to stay below all of these guidelines.

All of the guidelines you just learned should be considered absolute maximums, not goals.

While research shows moderate drinking is likely safe, there is a general trend that suggests you might do well to err on the side of less rather than more alcohol.

There’s also scant evidence showing alcohol has many significant health benefits, so if you don’t enjoy drinking, don’t start for health reasons.

Instead of aiming to drink as much alcohol as possible while still staying within the guidelines in this article, aim to drink as little as possible while still enjoying alcohol.

Personally, I drink maybe 4 or 5 servings of alcohol per year, mostly when visiting new places and trying different kinds of wine or beer, and that’s enough for me. Even if I became a wine fiend, I’d still probably limit myself to 3 or 4 glasses per week to err on the side of caution.

You obviously don’t have to be quite this ascetic (or boring), but I encourage you to see how little you can drink without causing yourself unnecessary discomfort (so long as you still follow the other guidelines in this article). For some people that may be a glass of wine per night, and for others it might be three or four beers on the weekend, and for others it may be no alcohol at all.

If you can’t drink moderately, don’t.

The biggest problem with “moderate drinking” is that many people don’t drink moderately.

This is particularly true of people who drink in order to get drunk, in which case one drink often turns into two, which turns into three, which turns into who-cares-I’m-finishing-this-bottle. The CDC reports 1 in 6 adults in the U.S. binge drinks at least once per week, and it’s possible that number could be even higher.

Others make the mistake of overindulging a little bit each day—drinking just enough to get tipsy or buzzed but not enough to appear slovely or unhinged.

Regardless of the reason, if you can’t stick to the guidelines for moderate drinking, you’re probably better off not drinking at all. The risks are many and the rewards are few and fleeting.

The Bottom Line on How Much Alcohol It’s Safe to Drink

Alcohol is both a drug and a source of calories, and it affects many different parts of the body.

Here are the most important things to know about alcohol and body composition:

- Drinking alcohol while in a calorie surplus and consuming lots of dietary fat can increase fat storage.

- Drinking alcohol while in a calorie deficit has no impact on body fat levels and may even offer some fat loss benefits.

- Drinking moderate amounts of alcohol doesn’t decrease with muscle growth, but drinking lots of alcohol decreases testosterone levels, slows recovery, and likely interferes with muscle growth.

(Oh, and if all this talk of calorie surpluses and deficits has got you confused about how many calories you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz)

A good working definition of “moderate drinking” is 30 to 40 grams per day or less for men and about half that for women. This works out to around one to two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women.

Although it’s often said that moderate drinking is good for you, in reality it’s probably benign. That is, it doesn’t offer any health benefits or pose any health risks to otherwise healthy people.

Research has consistently shown that heavy drinking is linked with many illnesses including cancer, heart attack, and liver disease as well as a significantly shorter lifespan.

When it comes to moderate drinking, here are some simple, evidence-based guidelines:

- Don’t drink more than 1 gram of alcohol per pound of body weight per week.

- Don’t drink more than 0.25 grams of alcohol per pound of body weight on any single day.

- Don’t get drunk more than a few times per year.

- Aim to stay below all of these guidelines (treat them as absolute maximums, not targets).

- If you can’t drink moderately, don’t.

Do that, and you should have no trouble enjoying alcohol without suffering any negative health consequences.

What do you think of how much alcohol it’s safe to drink? Have anything else to add? Lemme know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Esser MB, Hedden SL, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Gfroerer JC, Naimi TS. Prevalence of alcohol dependence among US adult drinkers, 2009-2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11(11). doi:10.5888/pcd11.140329

- Naimi TS, Xuan Z, Brown DW, Saitz R. Confounding and studies of “moderate” alcohol consumption: The case of drinking frequency and implications for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2013;108(9):1534-1543. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04074.x

- Reitsma MB, Fullman N, Ng M, et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885-1906. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X

- Study Causes Splash, but Here’s Why You Should Stay Calm on Alcohol’s Risks - The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/28/upshot/alcohol-health-risks-study-worry.html. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015-1035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2

- Wood AM, Kaptoge S, Butterworth A, et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet. 2018;391(10129):1513-1523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30134-X

- Towers A, Philipp M, Dulin P, Allen J. The “Health Benefits” of Moderate Drinking in Older Adults may be Better Explained by Socioeconomic Status. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. December 2016:gbw152. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw152

- Naimi TS, Xuan Z, Brown DW, Saitz R. Confounding and studies of “moderate” alcohol consumption: The case of drinking frequency and implications for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2013;108(9):1534-1543. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04074.x

- Molina PE, Nelson S. Binge Drinking’s Effects on the Body. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(1):99-109. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6104963/. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- Stahre M, Naimi T, Brewer R, Holt J. Measuring average alcohol consumption: The impact of including binge drinks in quantity-frequency calculations. Addiction. 2006;101(12):1711-1718. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01615.x

- Rehm J, Irving H, Ye Y, Kerr WC, Bond J, Greenfield TK. Are Lifetime Abstainers the Best Control Group in Alcohol Epidemiology? On the Stability and Validity of Reported Lifetime Abstention. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(8):866-871. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn093

- Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315(16):1750-1766. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4226

- Keil U, Chambless LE, Döring A, Filipiak B, Stieber J. The relation of alcohol intake to coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in a beer-drinking population. Epidemiology. 1997;8(2):150-156. doi:10.1097/00001648-199703000-00005

- Grønbœk M, Johansen D, Becker U, et al. Changes in alcohol intake and mortality: A longitudinal population-based study. Epidemiology. 2004;15(2):222-228. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000112219.01955.56

- Boffetta P, Garfinkel L. Alcohol drinking and mortality among men enrolled in an American Cancer Society prospective study. Epidemiology. 1990;1(5):342-348. doi:10.1097/00001648-199009000-00003

- Doll R, Peto R, Hall E, Wheatley K, Gray R. Mortality in relation to consumption of alcohol: 13 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 1994;309(6959):911. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6959.911

- Rehm J. The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol Res Heal. 2011;34(2):135-143. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3307043/. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- Klein WMP, Jacobsen PB, Helzlsouer KJ. Alcohol and Cancer Risk: Clinical and Research Implications. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. January 2019. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.19133

- Pompili M, Serafini G, Innamorati M, et al. Suicidal behavior and alcohol abuse. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(4):1392-1431. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041392

- Kuria MW, Ndetei DM, Obot IS, et al. The Association between Alcohol Dependence and Depression before and after Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:1-6. doi:10.5402/2012/482802

- Preedy VR, Paice A, Mantle D, Dhillon AS, Palmer TN, Peters TJ. Alcoholic myopathy: biochemical mechanisms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63(3):199-205. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00219-2

- Barnes MJ, Mündel T, Stannard SR. Post-exercise alcohol ingestion exacerbates eccentric-exercise induced losses in performance. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):1009-1014. doi:10.1007/s00421-009-1311-3

- Välimäki M, Tuominen JA, Huhtaniemi I, Ylikahri R. The Pulsatile Secretion of Gonadotropins and Growth Hormone, and the Biological Activity of Luteinizing Hormone in Men Acutely Intoxicated with Ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14(6):928-931. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01840.x

- Lieber CS. Perspectives: Do alcohol calories count? Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(6):976-982. doi:10.1093/ajcn/54.6.976

- Suter PM, Jéquier E, Schutz Y. Effect of ethanol on energy expenditure. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(4 Pt 2):R1204-12. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1204

- Arima H, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, et al. Alcohol reduces insulin-hypertension relationship in a general population: The Hisayama study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):863-869. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00441-9

- Kokavec A. Is decreased appetite for food a physiological consequence of alcohol consumption? Appetite. 2008;51(2):233-243. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.03.011

- Yeomans MR. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: Is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiol Behav. 2010;100(1):82-89. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.012

- Schutz Y. Role of substrate utilization and thermogenesis on body-weight control with particular reference to alcohol. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(4):511-517. doi:10.1017/s0029665100000744

- IRON TOXICITY. Nutr Rev. 1955;13(9):277-278. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1955.tb03528.x

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25353

- Battarbee HD, Meneely GR, Tobian L. The toxicity of salt. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1978;5(4):355-376. doi:10.3109/10408447809081011

- Kawahito S, Kitahata H, Oshita S. Problems associated with glucose toxicity: Role of hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(33):4137-4142. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.4137

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol Metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16(4):667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Siler SQ, Neese RA, Hellerstein MK. De novo lipogenesis, lipid kinetics, and whole-body lipid balances in humans after acute alcohol consumption. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(5):928-936. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.5.928

- Rusyn I, Bataller R. Alcohol and toxicity. J Hepatol. 2013;59(2):387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.035

- Hernández OH, Vogel-Sprott M, Ke-Aznar VI. Alcohol impairs the cognitive component of reaction time to an omitted stimulus: A replication and an extension. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(2):276-281. doi:10.15288/jsad.2007.68.276

- Goudriaan AE, Grekin ER, Sher KJ. Decision making and binge drinking: A longitudinal study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(6):928-938. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00378.x

- Morgan CJ. Alcohol-induced euphoria: exclusion of serotonin. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36(1):22-25. doi:10.1093/alcalc/36.1.22

- Cooper ML. Personality and close relationships: Embedding people in important social contexts. J Pers. 2002;70(6). doi:10.1111/1467-6494.05023

- Baum-Baicker C. The psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: A review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1985;15(4):305-322. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(85)90008-0

- Sayette MA. The effects of alcohol on emotion in social drinkers. Behav Res Ther. 2017;88:76-89. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.005

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23(7):959-997. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002

- Aas RW, Haveraaen L, Sagvaag H, Thørrisen MM. The influence of alcohol consumption on sickness presenteeism and impaired daily activities. The WIRUS screening study. PLoS One. 2017;12(10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186503

- Mäkelä P, Raitasalo K, Wahlbeck K. Mental health and alcohol use: A cross-sectional study of the Finnish general population. In: European Journal of Public Health. Vol 25. Oxford University Press; 2015:225-231. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cku133

- Srivastava S, Bhatia M. Quality of life as an outcome measure in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):41. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.123617

- Watzl, B., Bub, A., Briviba, K., & Rechkemmer, G. (2002). Acute intake of moderate amounts of red wine or alcohol has no effect on the immune system of healthy men. European Journal of Nutrition, 41(6), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-002-0384-0

- Watzl, B., Bub, A., Pretzer, G., Roser, S., Barth, S. W., & Rechkemmer, G. (2004). Daily moderate amounts of red wine or alcohol have no effect on the immune system of healthy men. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 58(1), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601742

- Kornum, J. B., Due, K. M., Nørgaard, M., Tjønneland, A., Overvad, K., Sørensen, H. T., & Thomsen, R. W. (2012). Alcohol drinking and risk of subsequent hospitalisation with pneumonia. European Respiratory Journal, 39(1), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00000611

- Ehlers, C. L., Liang, T., & Gizer, I. R. (2012). ADH and ALDH polymorphisms and alcohol dependence in Mexican and Native Americans. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 389–394. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.694526

- Ried, K., Frank, O. R., & Stocks, N. P. (2013). Aged garlic extract reduces blood pressure in hypertensives: A dose-response trial. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(1), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2012.178

- Heymann, H. M., Gardner, A. M., & Gross, E. R. (2018). Aldehyde-Induced DNA and Protein Adducts as Biomarker Tools for Alcohol Use Disorder. In Trends in Molecular Medicine (Vol. 24, Issue 2, pp. 144–155). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2017.12.003

- Kwok, A., Dordevic, A. L., Paton, G., Page, M. J., & Truby, H. (2019). Effect of alcohol consumption on food energy intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In British Journal of Nutrition (Vol. 121, Issue 5, pp. 481–495). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518003677