The Jefferson curl has recently become a hot topic in the weightlifting community.

Proponents hail it as a powerful solution for combating back problems and offering long-term pain relief.

Others argue it’s a dangerous movement that greatly increases your risk of back injury.

What’s the truth? Who should incorporate the exercise into their routine? And how do you do Jefferson curls with correct form?

Get evidence-based answers to these questions and more in this article.

Who Should Do the Jefferson Curl Exercise?

The Jefferson curl is a divisive exercise in the fitness world.

On the one hand, experts, including Dr. Stuart McGill, warn that flexing (bending) your spine while lifting weights can compromise spine health and increase the risk of disc herniations. Because of these risks, they advise everyone to avoid the Jefferson curl.

On the other hand, many believe there’s little compelling evidence this is true and that flexion exercises aren’t inherently dangerous. They argue that if exercises like the Jefferson curl were harmful, we’d see a higher incidence of back pain among people who flex their spine for extended periods or repeatedly flex their spine against resistance—but we don’t.

Furthermore, they believe weightlifting strengthens your muscles and bones, making injuries less likely, and recommend the Jefferson curl for everyone, especially those with back issues.

Indeed, both sides make valid points but also have weaknesses in their arguments.

For example, critics of spine flexion exercises often base their views on unrealistic animal studies, which might not directly apply to humans lifting weights. On the other hand, flexion exercise advocates typically don’t support their stance with studies on weightlifters, making it hard to see if their claims hold up in practice.

Furthermore, there’s debate about whether exercises like the Jefferson curl strengthen the spine, as the spinal discs might not respond to strength training the same way other bones do.

So, who should you listen to? And should anyone actually do the Jefferson curl exercise?

In reality, taking an extreme stance in either direction isn’t prudent.

Back pain varies significantly between people, and different movements can affect it differently. For instance, some people find spinal flexion painful and get relief from arching their back (they have an “extension bias”). These people probably shouldn’t do the Jefferson curl.

Others find spinal extension problematic, but flexion feels good. These people have a “flexion bias,” and performing the Jefferson curl may offer some benefit.

In other words, the Jefferson curl isn’t a cure-all for back pain. It might help in some cases; in others, it could cause problems.

Here are some heuristics for using it as a treatment for back pain:

- Start using only your body weight and see how it feels.

- If it causes discomfort, stop.

- If it feels okay, continue with light weights and progress slowly.

If you don’t have back pain, whether you try the exercise is up to you. If you try it and enjoy it, there’s no harm in continuing. But bear in mind that it’s not essential for most people.

In fact, the only people without back pain who might benefit from doing Jefferson curls are those who must be strong in a range of positions—first responders, military personnel, strongmen, gymnasts, grapplers, and the like.

How to Do the Jefferson Curl

- Hold a barbell with an overhand grip (palms facing you) and stand upright on a box, bench, or other sturdy elevated surface.

- Keeping the bar close to your legs, slowly bend forward to lower the weight toward the floor. Focus on moving one vertebra at a time, starting at the top of your neck and working your way down your spine.

- Continue lowering the weight as far as possible while keeping your legs straight.

- Reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

Here’s how it should look when you put it all together:

Jefferson Curl: Benefits

Here are the primary Jefferson curl benefits:

1. It strengthens your posterior chain.

The Jefferson curl trains your entire posterior chain (the muscle groups on the back of your body). It also trains the lower back in a flexed position, which most other exercises neglect. This may promote more balanced and complete strength than if you only do exercises with a neutral spine.

2. It stretches your hamstrings.

Performing Jefferson curls through a full range of motion deeply stretches the hamstrings, which can become tight among people who spend extended periods of time sitting and contribute to lower back pain.

3. It may improve back pain.

While research has yet to verify claims that the Jefferson curl can improve back pain, countless anecdotal reports suggest it can. Importantly, this is likely only true in people with a flexion bias.

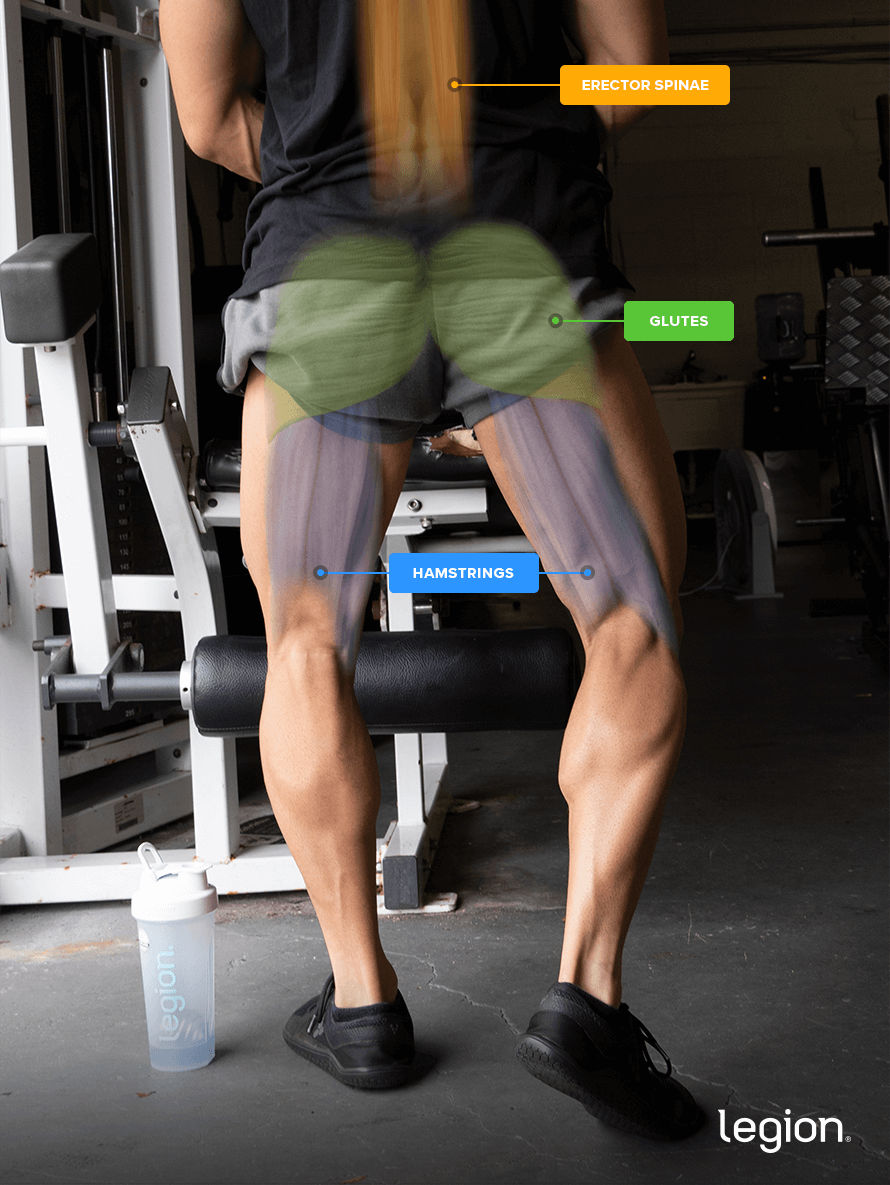

Jefferson Curl: Muscles Worked

When performing the Jefferson Curl, the primary muscles worked are:

- Erector spinae (lower back)

- Hamstrings

- Glutes

It also trains the traps, rhomboids, lats, calves, and core to a lesser extent.

Here’s how the main muscles worked by the Jefferson curl look on your body:

Jefferson Curls: FAQs

FAQ #1: What does a Jefferson curl do?

The Jefferson curl strengthens the lower back and stretches the hamstrings. It trains the lower back while flexed, promoting strength and flexibility in a position that most other exercises miss.

FAQ #2: What is the function of the Jefferson curl?

The primary function of the Jefferson curl is to build strength and increase mobility in the spine and hamstrings. Some people believe the Jefferson curl can help prevent or cure lower back pain, but this isn’t based on scientific evidence yet.

FAQ #3: Are Jefferson curls good for lower back pain?

Jefferson curls can benefit people with lower back pain, especially those with a flexion bias—meaning they find comfort in bending forward. While scientific research is limited, anecdotal evidence suggests that the Jefferson curl may help alleviate back pain for some individuals by strengthening and stretching the lower back and hamstrings.

However, it’s essential to start with no or very light weights and progress slowly to ensure the exercise doesn’t exacerbate the pain. Lifting heavy weights is rarely necessary for this exercise.

FAQ #4: What is the difference between Jefferson curls and good mornings?

The difference between Jefferson curls and good mornings is Jefferson curls strengthen your lower back when it’s bent, and good mornings strengthen your lower back, glutes, and hamstrings while your back is straight.

Good mornings let you lift heavier weights more safely, so they’re typically more common in strength and conditioning programs designed to help you gain muscle and strength.

Scientific References +

- McGill, Stuart M, et al. “Changes in Lumbar Lordosis Modify the Role of the Extensor Muscles.” Clinical Biomechanics, vol. 15, no. 10, Dec. 2000, pp. 777–780, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0268-0033(00)00037-1. Accessed 21 Apr. 2021.

- Gunning, Jennifer L, et al. “Spinal Posture and Prior Loading History Modulate Compressive Strength and Type of Failure in the Spine: A Biomechanical Study Using a Porcine Cervical Spine Model.” Clinical Biomechanics, vol. 16, no. 6, July 2001, pp. 471–480, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00032-8.

- Callaghan, Jack P, and Stuart M McGill. “Intervertebral Disc Herniation: Studies on a Porcine Model Exposed to Highly Repetitive Flexion/Extension Motion with Compressive Force.” Clinical Biomechanics, vol. 16, no. 1, Jan. 2001, pp. 28–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0268-0033(00)00063-2. Accessed 25 Feb. 2022.

- Veres, Samuel P., et al. “The Morphology of Acute Disc Herniation: A Clinically Relevant Model Defining the Role of Flexion.” Spine, vol. 34, no. 21, 1 Oct. 2009, pp. 2288–2296, journals.lww.com/spinejournal/Fulltext/2009/10010/The_Morphology_of_Acute_Disc_Herniation__A.9.aspx, https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a49d7e. Accessed 30 Sept. 2020.

- D’Ambrosia, Peter, et al. “Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Expression Increases Following Low- and High-Magnitude Cyclic Loading of Lumbar Ligaments.” European Spine Journal, vol. 19, no. 8, 25 Mar. 2010, pp. 1330–1339, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989207/, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1371-4. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

- Howe, Louis , and Gregory Lehman . Getting out of Neutral: The Risks and Rewards of Lumbar Spine Flexion during Lifting Exercises. Mar. 2021.

- Foss, Ida Stange, et al. “The Prevalence of Low Back Pain among Former Elite Cross-Country Skiers, Rowers, Orienteerers, and Nonathletes.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 40, no. 11, 12 Sept. 2012, pp. 2610–2616, https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546512458413. Accessed 9 Jan. 2020.

- BELAVY, DANIEL L., et al. “Beneficial Intervertebral Disc and Muscle Adaptations in High-Volume Road Cyclists.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 51, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 211–217, jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/63830/beneficial%20intervertebral%20disc%20and%20muscle%20adaptations.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000001770.

- Hong, A Ram, and Sang Wan Kim. “Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 33, no. 4, 2018, p. 435, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6279907/, https://doi.org/10.3803/enm.2018.33.4.435.

- Heüveldop, Sophie, et al. “Assessment of Glycosaminoglycan Content of Lumbar Intervertebral Discs in Patients with Radiculopathy.” International Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 10, no. 04, 2019, pp. 259–269, https://doi.org/10.4236/ijcm.2019.104020. Accessed 21 Aug. 2022.

- Albeshri, ZainabSaeed, and EnasFawzy Youssef. “The Immediate Effect of Kinesio Tape on Hamstring Muscle Length and Strength in Female University Students: A Pre–Post Experimental Study.” Saudi Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, vol. 11, no. 1, 2023, p. 73, https://doi.org/10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_585_22. Accessed 15 Apr. 2023.