Key Takeaways

- Researchers had one group of elite athletes maintain a daily calorie deficit of 300 calories and another group maintain a daily deficit of 750 calories.

- The 750 calorie deficit group lost 4 times more body fat over 4 weeks without losing significantly more muscle than the 300 calorie deficit group.

- If you want to lose fat as fast as possible without losing muscle, then reduce your calories by 25%, not 10%.

Let’s be real: dieting sucks.

The benefits of getting lean are worth it, of course, but it’s always a challenge.

One solution to that problem is to get it over with as fast as possible.

The sooner you reach your goal body fat percentage, the sooner you can eat more and focus on either maintaining your physique or building muscle again.

On the other hand, you also don’t want to lose muscle, crash your hormones, or watch your strength in the gym plummet, which you’ve heard can happen when you lose weight too fast.

So, how fast can you lose weight without losing muscle or messing up your metabolism?

That’s what scientists at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland wanted to find out in a study published in 2015.

Let’s look at what they did.

What Did the Researchers Do?

The researchers had 15 elite male track-and-field athletes record their diet and training for 4 days.

Then, they had them follow a high-protein, low-calorie diet for 4 weeks.

They split the athletes into 2 groups:

- One group would follow a diet that provided 300 calories fewer than they burned every day (a 10% deficit).

- One group would follow a diet that provided 750 calories fewer than they burned every day (a 25% deficit).

All of these athletes were about 10% body fat, too, which made it more likely they would lose muscle mass.

To help prevent this, everyone ate about 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight per day and reduced their calorie intake by eating fewer carbs and fats.

All of the participants maintained the same training program that they used before the study.

To help everyone stick to the diet, the researchers worked with the athletes to create meal plans based on their preferred food choices. In other words, they followed standard flexible dieting principles.

Before and after the study, the researchers measured:

1. Body composition.

They measured body composition using a DXA machine, which uses x-rays to measure someone’s lean body mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density.

While it’s not perfect, it’s considered the gold standard for measuring changes in body fat and muscle mass.

2. Hormone levels, including testosterone, cortisol, and sex hormone-binding globulin.

Calorie restriction often reduces testosterone levels in men, which can cause muscle loss, poor mood, and low energy levels.

Increased cortisol levels indicate greater total body stress, and can also contribute to muscle loss if they stay high long enough.

Sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) is a molecule that binds to testosterone so that it can’t exert its beneficial effects. SHBG levels often rise when calories are low, which can indirectly reduce free testosterone levels.

3. Athletic performance.

The researchers measured countermovement jump performance, which is a good indicator of explosive power, and 20-meter sprint performance, which is a measure of speed.

The researchers also provided multivitamin supplements, and forbid anyone from using creatine. This is because creatine is known to increase lean body mass and performance, which could confound the results.

Recommended Reading:

→ What 17 Studies Say About Increasing Your Testosterone Naturally

What Were the Study Results?

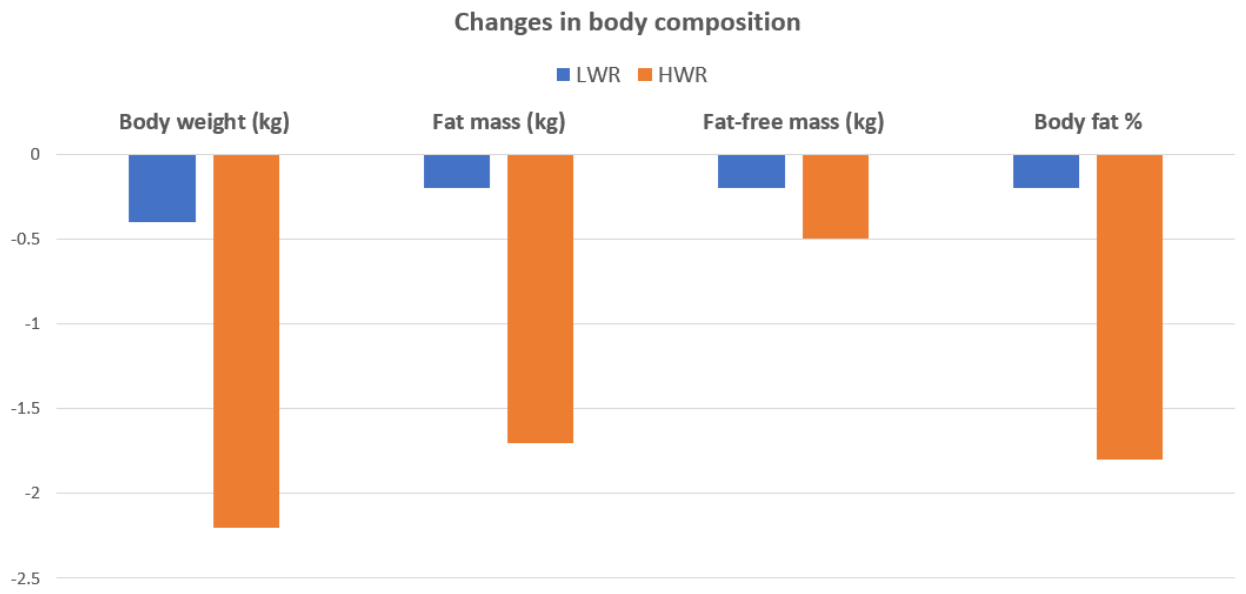

Both groups maintained their muscle mass and performance, but the 750 calorie deficit group lost 4 times as much fat after 4 weeks of dieting.

Now, before we get too excited, it’s worth mentioning that the differences between both groups weren’t statistically significant.

That is, there was a high enough chance that the results were due to random variation that the researchers couldn’t say the different diets were responsible for the different results.

There’s a problem with taking that conclusion at face value, though. There were only 7 people in the 300 calorie deficit group and 8 people in the 750 calorie deficit group.

It’s possible that if there were more people in the study the results would have been statistically significant.

With that in mind, it’s clear that there were meaningful differences between the 2 groups.

The 750 calorie deficit group lost 5 pounds of body weight and 4 pounds of fat. The 300 deficit group lost a paltry 1 pound of body weight and only ½ a pound of fat.

Here’s what the changes in body composition looked like:

The “HWR” group is the one that maintained a 750 calorie deficit, and the “LWR” group is the one that maintained a 300 calorie deficit.

It also looks like both groups lost a small amount of lean body mass, though it’s likely that was mostly due to losing water and glycogen than muscle mass.

Both groups also maintained their performance throughout the study, and the 750 calorie deficit group even improved their countermovement jump performance (not too surprising since they weighed less).

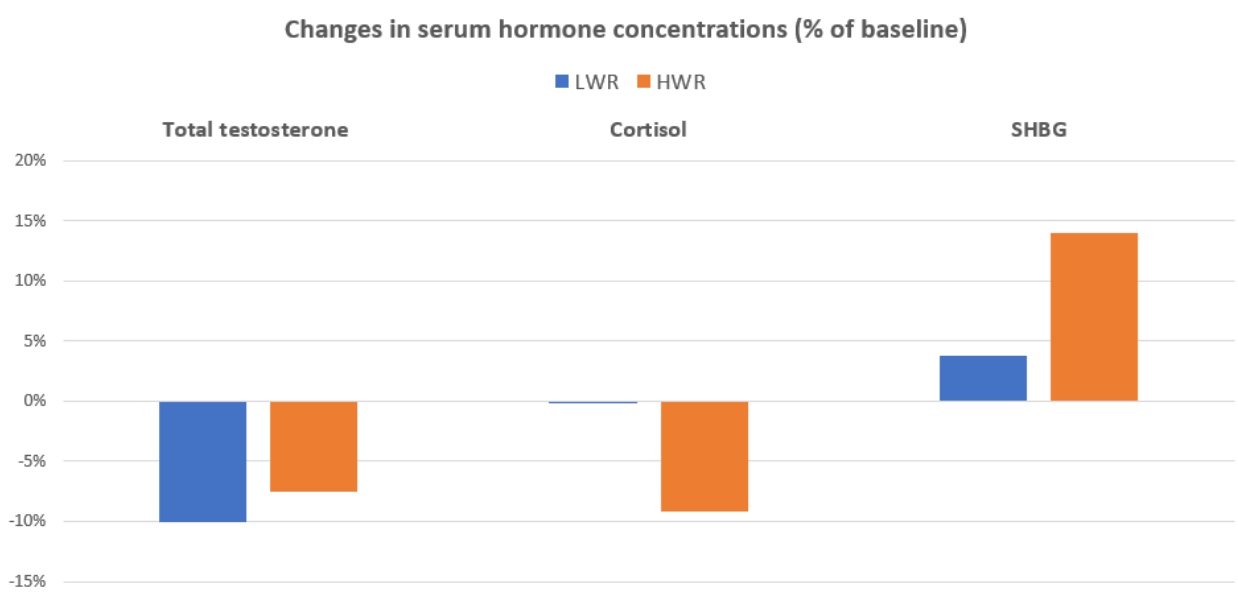

There weren’t any statistically significant differences in hormone levels, either, but there were a few small changes worth noting.

Here are the Cliff Notes:

- The 750 calorie group had a larger increase in cortisol.

- The 750 calorie group had a larger increase in SHBG.

- The 300 calorie deficit group had a slightly larger decrease in total testosterone.

So, this is more or less what you’d expect.

The group that maintained the more aggressive calorie deficit had slightly larger drops in testosterone and a slightly larger increase in cortisol, which makes sense since they lost more weight.

The rise in SHBG in the 750 calorie deficit group also means that their free testosterone levels were probably lower at the end of the study, which might seem like proof that rapid weight loss messes up your hormones.

There are 2 reasons that’s probably not the case, though.

- All of the values remained within the normal ranges, so it’s unlikely they would have translated into any real-world differences.

- Hormonal changes due to calorie restriction primarily depend on the degree of weight loss. The 750 calorie deficit group lost more fat, so they had a larger change in some hormones. It’s likely that the 300 calorie deficit would also have experienced similar changes if they dieted long enough to lose the same amount of weight.

In the big scheme of things, the changes in hormone levels in both groups were too small to have any practical significance.

Recommended Reading:

→ Why Rapid Weight Loss Is Superior to “Slow Cutting” (And How to Do It Right)

What Does This Mean for You?

Sometimes, faster weight loss is better than slower weight loss.

In this study, reducing calories by 25% caused 4 times more fat loss and than reducing calories by 10%, with no difference in muscle loss.

And this was in people who were already 10% body fat to begin with.

Not only is this more efficient, it’s also more motivating. Most research shows that people who lose the most weight in the first few weeks of dieting also lose the most weight long term and do the best job of keeping it off.

Why?

Because nothing keeps you on track better than results.

That said, there is a limit to how fast you can lose fat without losing muscle.

Other researchers have suggested that the maximum weekly rate of weight loss should be 0.5 to 1% of body weight per week, which is about how fast these athletes lost weight.

That’s 2 pounds per week if you weigh 200 pounds. That’s almost 10 pounds per month. That’s motivating.

To make this work, though, you need to get a few things right:

- You should eat around 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight. (And if you’d like more specific advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your weight-loss goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz.)

- You should maintain your training volume and intensity while restricting calories. If you want to increase your chances of maintaining or even gaining muscle while cutting, then you want to focus on heavy, compound strength training in your workouts, too.

- You should create a meal plan that ensures you get enough protein and whole, nutritious, filling foods, which is exactly what these athletes did.

Do that, and you can lose weight fast without losing muscle.

If you want to learn even more about exactly how to set up a diet, training, and supplementation plan to lose weight fast the right way, then check out this article:

→ The Complete Guide on How to Safely and Healthily Lose Weight Fast

What’s your take on losing fat fast without losing muscle? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- K, E., & S, R. (2005). Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Reviews : An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 6(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-789X.2005.00170.X

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- AR, H., & ML, Z. (1996). Relationships between testosterone, cortisol and performance in professional cyclists. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 17(6), 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2007-972872

- JN, R., & WE, S. (1997). Weight loss and wrestling training: effects on growth-related hormones. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 82(6), 1760–1764. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPL.1997.82.6.1760

- TA, K., P, S., M, M., T, S., A, M., & K, T. (2008). Rapid weight loss decreases serum testosterone. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 29(11), 872–877. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2008-1038604

- F, B., F, L., M, C., RA, F., M, V., K, E., S, M., E, D., NM, A.-D., S, A., J, B., I, B., ML, B., O, B., T, C., F, C., A, C., C, C., A, C.-J., … JA, K. (2018). Pitfalls in the measurement of muscle mass: a need for a reference standard. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 9(2), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/JCSM.12268