If you don’t like something of ours, guess what happens next?

No, we don’t request you deliver it to a PO box in the Gobi Desert by carrier pigeon. Nor do we ask you to fill a cursed inkwell with orc’s blood and demon saliva and then use it to complete reams of return forms written in ancient Cyrillic script.

We just . . . wait for it . . . give you every penny of your money back. Holy moo cows. And that means you can say "yes" now and decide later.

Notice to California Consumers

WARNING: Consuming this product can expose you to chemicals including lead which is known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm. For more information go to www.P65Warnings.ca.gov/food.

Legion Genesis Ingredients (13.5 grams per serving)

Organic Spirulina (6 grams per serving)

Spirulina is a cyanobacterium (a type of bacteria that can make their own food from sunlight) that’s one of nature’s richest and most complete sources of vital nutrients. It’s especially high in B vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, and a powerful antioxidant compound called phycocyanin.

Research shows that supplementation with spirulina . . .

- Supports immune function[8][9]

- Enhances strength and endurance[10][11]

- Delays the onset of exercise-induced fatigue[12]

- Supports fat loss[13][14]

- Reduces exercise-induced muscle damage[15]

- Supports liver health[16]

- Helps the body eliminate heavy metals[17]

The clinically effective dose of spirulina is between 2 and 10 grams, with most benefits seen in the 5-to-10-gram range.

Astragalus Membranaceus (3 grams per serving)

Astragalus membranaceus (also known as Mongolian milkvetch) is a herb that has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine to boost stamina and vitality and promote longevity.

It contains numerous beneficial compounds, including flavanoids and polysaccharides, but one of the more notable is astragaloside IV—a compound that helps protect cells from oxidative stress.[18]

Research shows that supplementation with Astragalus membranaceus . . .

- Supports immune function, even during periods of physical stress[19][20][21]

- Reduces muscle damage and may help restore strength faster after training[22]

- May help protect cells from oxidative stress[23]

- May support healthy aging by promoting DNA integrity[24][25]

The clinically effective dose of Astragalus membranaceus is 15 grams of the raw root. Genesis contains 3 grams of a 5:1 Astragalus membranaceus extract per serving, providing the equivalent of 15 grams of the raw root.

Organic Matcha Tea (3 grams per serving)

Matcha is a powdered form of Japanese green tea. Unlike regular green tea, matcha leaves are shaded several weeks before harvest, then steamed, destemmed, and stone-ground to preserve their nutritional profile.

As a result, matcha is rich in epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a substance linked to a range of cognitive benefits, and theanine, an amino acid that regulates neurotransmitters involved in mood and focus.

EGCG also helps you maintain a healthy body composition by slowing the breakdown of norepinephrine, a chemical that increases energy expenditure and fat burning.

Research shows that supplementation with matcha tea . . .

- Supports cognitive performance[26][27]

- Increases energy expenditure and fat burning[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

- May enhance the fat-burning effects of exercise[36][37][38][39]

The clinically effective dose of matcha tea is 2-to-3 grams per day.

Maca (1.5 grams per serving)

Maca (also known as Lepidium meyenii) is a plant native to the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia. Its root has been cultivated for thousands of years, and was an integral part of the diet and commerce of the ancient Incan civilization.

It contains a variety of bioactive compounds, including alkaloids, glucosinolates, and macamides, which influence nerve communication, brain chemistry, and various regulatory pathways.

Research shows that supplementation with maca . . .

- Supports mood and well-being[40][41][42]

- Supports sexual function and libido in men and women[43][44][45]

- Improves sperm production and quality[46]

- May improve energy levels[47]

- May enhance endurance, strength, and power[48][49]

The clinically effective dose of maca extract is between 1 and 3 grams per day.

Naturally Sweetened and Flavored

While artificial sweeteners may not be as dangerous as some people claim, studies suggest that regular consumption of these chemicals may indeed be harmful to our health.[50][51][52][53][54][55]

That’s why we use the natural sweetener stevia instead. Research shows that this ingredient is not only safe but can also confer several health benefits, including better nutrient absorption, healthy cholesterol levels, and more.[56][57][58][59]

No Artificial Food Dyes, Fillers, or Other Unnecessary Junk

As with artificial sweeteners, studies show that artificial food dyes and fillers can cause negative effects in some people, including gastrointestinal toxicity and behavioral disorders.[60][61][62][63][64]

That’s why we use natural coloring and flavoring derived from fruits and other foods as well as naturally derived ingredients for improving texture, enhancing shelf life, and facilitating the manufacturing process.

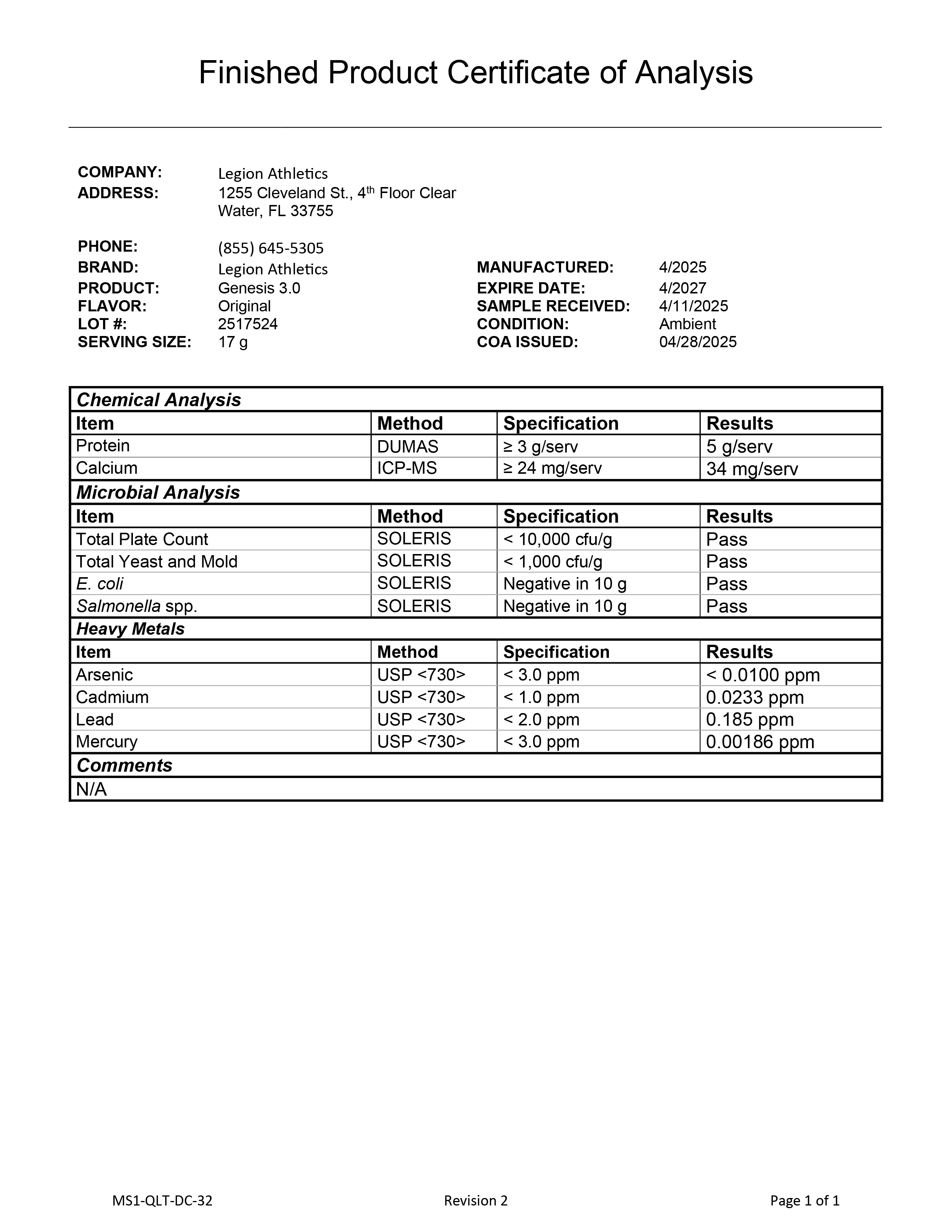

Third-Party Lab Tested for Purity and Potency

Genesis is tested by a state-of-the-art ISO 17025-accredited third-party laboratory for heavy metals, microbes, allergens, and other contaminants to ensure compliance with FDA purity standards.

See how Legion Genesis compares to the rest.

- Active Ingredients

- Clinically Effective Ingredients and Doses

- Organic Spirulina

- Astragalus Membranaceus

- Organic Matcha Tea

- Maca

- Naturally Sweetened and Flavored

- Third-Party Lab Tested

- Labdoor Certified Brand

- Price Per Serving

-

Legion

Genesis

- 13.5 g

per serving - 6 g

per serving - 3 g

per serving - 3 g

per serving - 1.5 g

per serving - $

-

Athletic

Greens

- 10.31 g

per serving

(proprietary blend)

(proprietary blend)- $3.30

-

Organifi

Greens Juice

- 7.05 g

per serving

(proprietary blend)

(proprietary blend)- $2.33

-

1stPhorm

Opti-Greens 50

- 9.03 g

per serving

(proprietary blend)- $2.17

The #1 brand of naturally sweetened and flavored sports supplements.

We’ve sold over 5 million bags and bottles to over 1 million customers in 169 countries who have left us over 55,000 5-star reviews.

Clinically Effective Ingredients and Doses

Every active ingredient, form, and dose in Genesis is backed by peer-reviewed scientific research demonstrating clear benefits in healthy humans.

Naturally Sweetened and Flavored

Genesis is naturally sweetened with stevia and naturally flavored with extracts from fruit, vegetables, plants and other foods.

Total Label Transparency

We clearly list the dose of each ingredient in Genesis on the label—no proprietary blends or hidden ingredients—so you can verify our formulation’s validity and effectiveness.

Third-Party Lab Tested for Purity and Potency

Genesis is tested by a state-of-the-art ISO 17025-accredited third-party laboratory for heavy metals, microbes, allergens, and other contaminants to ensure compliance with FDA purity standards.

Made in the USA

Genesis is made in America with globally sourced ingredients in NSF-certified, FDA-inspected facilities that adhere to Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) standards.

100% Money-Back Guarantee

If you don't absolutely love Genesis, you get a prompt and courteous refund. No forms or returns necessary.

Trusted by scientists, doctors, and everyday fitness folk alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

+References

Some popular greens supplements are naturally sweetened and flavored. Some contain the right mix of high-quality ingredients. Some provide clinically effective doses. But only Genesis checks each of these boxes. ↑

While artificial sweeteners may not be as dangerous as some people claim, studies suggest that regular consumption of these chemicals may indeed be harmful to our health. That’s why we use the natural sweetener stevia instead. ↑

Every serving of Genesis contains 13.5 grams of active ingredients that have been shown to be safe and effective in peer-reviewed scientific research. ↑

Each active ingredient in Genesis is backed by published scientific studies that show benefits in healthy humans. ↑

That’s 361 pages of scientific research that shows Genesis works exactly like we say it does. ↑

While artificial sweeteners may not be as dangerous as some people claim, studies suggest that regular consumption of these chemicals may indeed be harmful to our health. That’s why we use the natural sweetener stevia instead. ↑

Every bottle of Genesis is guaranteed to provide exactly what the label claims and nothing else—no heavy metals, microbes, allergens, or other contaminants. ↑

Nielsen CH, Balachandran P, Christensen O, et al. Planta Med. Nov 2010;76(16):1802-8. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250043 ↑

Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wu W, et al. Nutrients. 2022;14(20):4346. Published 2022 Oct 17. doi:10.3390/nu14204346. ↑

Chaouachi M, Gautier S, Carnot Y, et al. J Diet Suppl. 2021;18(6):682-697. doi:10.1080/19390211.2020.1832639 ↑

Kalafati M, Jamurtas AZ, Nikolaidis MG, et al. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Jan 2010;42(1):142-51. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ac7a45 ↑

Gurney T, Spendiff O. Eur J Appl Physiol. Dec 2020;120(12):2657-2664. doi:10.1007/s00421-020-04487-2 ↑

Moradi S, Ziaei R, Foshati S, Mohammadi H, Nachvak SM, Rouhani MH. Complement Ther Med. Dec 2019;47:102211. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102211 ↑

Bagheri R, Negaresh R, Motevalli MS, et al. Br J Nutr. Jan 28 2022;127(2):248-256. doi:10.1017/s000711452100091x ↑

Lu HK, Hsieh CC, Hsu JJ, Yang YK, Chou HN. Eur J Appl Physiol. Sep 2006;98(2):220-6. doi:10.1007/s00421-006-0263-0 ↑

. Lik Sprava. Sep 2000;(6):89-93. Kliniko-eksperymental'ne doslidzhennia efektyvnosti spiruliny pri khronichnykh dyfuznykh zakhvoriuvanniakh pechinky. ↑

Misbahuddin M, Islam AZ, Khandker S, Ifthaker Al M, Islam N, Anjumanara. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2006;44(2):135-41. doi:10.1080/15563650500514400 ↑

Ren S, Zhang H, Mu Y, Sun M, Liu P. IV: a literature review. J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;33(3):413-416. doi:10.1016/s0254-6272(13)60189-2 ↑

Zwickey H, Brush J, Iacullo CM, et al.. Phytother Res. Nov 2007;21(11):1109-12. doi:10.1002/ptr.2207 ↑

. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Aug 6 2004;320(4):1103-11. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.065 ↑

Latour E, Arlet J, Latour EE, et al. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. Jul 16 2021;18(1):57. doi:10.1186/s12970-021-00425-5 ↑

Yeh TS, Lei TH, Barnes MJ, Zhang L. Nutrients. Oct 17 2022;14(20)doi:10.3390/nu14204339 ↑

Ren S, Zhang H, Mu Y, Sun M, Liu P. J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;33(3):413-416. doi:10.1016/s0254-6272(13)60189-2 ↑

Bernardes de Jesus B, Schneeberger K, Vera E, Tejera A, Harley CB, Blasco MA.. Aging Cell. 2011;10(4):604-621. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00700.x ↑

Salvador L, Singaravelu G, Harley CB, Flom P, Suram A, Raffaele JM. Rejuvenation Res. 2016;19(6):478-484. doi:10.1089/rej.2015.1793 ↑

Sakurai K, Shen C, Ezaki Y, et al. Nutrients. Nov 26 2020;12(12). doi:10.3390/nu12123639. ↑

Baba Y, Kaneko T, Takihara T. Nutr Res. Apr 2021;88:44-52. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2020.12.024 ↑

Willems MET, Şahin MA, Cook MD. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. Sep 1 2018;28(5):536-541. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0237 ↑

Willems MET, Fry HL, Belding MA, Kaviani M. J Diet Suppl. 2021;18(5):566-576. doi:10.1080/19390211.2020.1811443 ↑

Dulloo AG, Duret C, Rohrer D, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. Dec 1999;70(6):1040-5. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.6.1040 ↑

Kapoor MP, Sugita M, Fukuzawa Y, Okubo T. J Nutr Biochem. May 2017;43:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.10.013. ↑

Auvichayapat P, Prapochanung M, Tunkamnerdthai O, et al. Physiol Behav. Feb 27 2008;93(3):486-91. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.009 ↑

Rondanelli M, Riva A, Petrangolini G, et al. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):644. Published 2021 Feb 17. doi:10.3390/nu13020644. ↑

Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM. Obes Res. Jul 2005;13(7):1195-204. doi:10.1038/oby.2005.142 ↑

Hursel R, Viechtbauer W, Westerterp-Plantenga MS.. Int J Obes (Lond). Sep 2009;33(9):956-61. doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.135 ↑

Maki KC, Reeves MS, Farmer M, et al. J Nutr. Feb 2009;139(2):264-70. doi:10.3945/jn.108.098293 ↑

Willems MET, Şahin MA, Cook MD. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. Sep 1 2018;28(5):536-541. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0237 ↑

Cardoso GA, Salgado JM, Cesar MdC, Donado-Pestana CM. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2013/02/01 2012;16(2):120-127. doi:10.1089/jmf.2012.0062 ↑

Br J Clin Pharmacol. Apr 2020;86(4):753-762. doi:10.1111/bcp.14176 ↑

G. Cicero, Linda Valmorri, Melissa Mercuriali, and Eduard Bercovich, ” Andrologia 41, no. 2 (2009): 95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2008.00892.x. ↑

Gonzales-Arimborgo C, Yupanqui I, Montero E, et al.. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2016;9(3):49. Published 2016 Aug 18. doi:10.3390/ph9030049 ↑

Brooks NA, Wilcox G, Walker KZ, Ashton JF, Cox MB, Stojanovska L. Menopause. 2008;15(6):1157-1162. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181732953. ↑

Brooks NA, Wilcox G, Walker KZ, Ashton JF, Cox MB, Stojanovska L. Menopause. 2008;15(6):1157-1162. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181732953. ↑

Gonzales, Amanda Córdova, Karla Vega, Arturo Chung, Arturo Villena, Carmen Góñez, and Sonia Castillo, Andrologia 34, no. 6 (2002): 367–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2002.00519.x; ↑

meyenii) for the Management of SSRI-Induced Sexual Dysfunction,” Christina M. Dording, Lauren Fisher, George Papakostas, Amy Farabaugh, Shamsah Sonawalla, Maurizio Fava, and David Mischoulon, CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 14, no. 3 (2008): 182–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00052.x. ↑

Gonzales, Amanda Cordova, Carla Gonzales, Arturo Chung, Karla Vega, and Arturo Villena, ” Asian Journal of Andrology 3, no. 4 (2001): 301–03. ↑

Gonzales-Arimborgo C, Yupanqui I, Montero E, et al. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2016;9(3):49. Published 2016 Aug 18. doi:10.3390/ph9030049 ↑

. Nutrients. 2023;15(7):1618. Published 2023 Mar 27. doi:10.3390/nu15071618 ↑

Stone M, Ibarra A, Roller M, Zangara A, Stevenson E. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;126(3):574-576. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.012 ↑

Abou-Donia MB, El-Masry EM, Abdel-Rahman AA, McLendon RE, Schiffman SS. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71(21):1415-1429. ↑

Qin X. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(9):511. doi:10.1155/2011/451036 ↑

Schernhammer ES, Bertrand KA, Birmann BM, Sampson L, Willett WC, Feskanich D. [published correction appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2013 Aug;98(2):512]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(6):1419-1428. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.030833 ↑

Fowler SP, Williams K, Resendez RG, Hunt KJ, Hazuda HP, Stern MP.. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(8):1894-1900. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.284 ↑

Sylvetsky A, Rother KI, Brown R. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(6):1467-xi. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.09.007 ↑

Neuroscience 2010. Yale J Biol Med. 2010;83(2):101-108. ↑

Yadav SK, Guleria P.. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2012;52(11):988-998. doi:10.1080/10408398.2010.519447. ↑

Shivanna N, Naika M, Khanum F, Kaul VK.. J Diabetes Complications. 2013;27(2):103-113. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.10.001 ↑

World Health Organization. WHO Food Additives Series, No. 60. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. ↑

Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2009. World Health Organization; 2010. Accessed May 9, 2025. ↑

Feng J, Cerniglia CE, Chen H. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4(2):568-586. Published 2012 Jan 1. doi:10.2741/e400 ↑

Kanarek RB. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(7):385-391. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00385.x. ↑

Nigg JT, Lewis K, Edinger T, Falk M. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):86-97.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.015 ↑

McCann D, Barrett A, Cooper A, et al. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2007 Nov 3;370(9598):1542]. Lancet. 2007;370(9598):1560-1567. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61306-3. ↑

Gao Y, Li C, Shen J, Yin H, An X, Jin H.. J Food Sci. 2011;76(6):T125-T129. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02267.x. ↑