It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn whether the consistency of the food you eat affects weight loss, one of the best exercises for training your hamstrings, and if using a massage gun improves flexibility.

Eating hard foods may boost weight loss.

Source: “Texture-based differences in eating rate influence energy intake for minimally processed and ultra-processed meals” published on July 6, 2022 in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

Some scientists speculate that one of the reasons eating ultra-processed food causes weight gain is that it tends to be softer, which means you typically eat it more quickly. And when you eat more quickly, your “hunger hormones” don’t have enough time to communicate fullness, which often means you overeat.

To test this theory, scientists at the Singapore Institute of Food and Biotechnology Innovation had 50 people consume 4 different meals on 4 separate occasions to assess how different textures and degrees of processing affect food intake.

The foods the diners ate were either soft-textured and minimally processed, soft-textured and ultra-processed, hard-textured and minimally processed, or hard-textured and ultra-processed. In each condition, the diners ate until they were comfortably full.

The results showed that diners ate more soft- than hard-textured food because they could eat it more quickly.

The diners ate the most calories during the soft-textured ultra-processed meal, followed by the soft-textured minimally processed meal, then the hard-textured ultra-processed meal, and finally, the hard-textured minimally processed meal. This pattern was the same for the rate of energy intake (calories consumed per minute) in each meal.

Despite these results, the diners felt equally full after each meal. They also consumed about the same number of calories throughout the remainder of the day, regardless of which test meal they ate. That is, when they ate fewer calories during the test meal, they didn’t compensate by eating more later in the day.

The findings from several other similar studies bolster these results, too.

If you want help controlling your appetite and limiting your food intake while dieting to lose weight, it’s sensible to get the majority of your calories from foods that require a bit of chewing.

Of course, most whole, nutritious, minimally processed foods like fruits, vegetables, beans, seafood, and meats fit this description, so this is really just more reason to prioritize these foods over nutritionally bankrupt fodder.

(And if you’d like even more advice about which foods you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: One of the reasons whole foods help you stay lean is they’re usually harder and require more chewing. This forces you to eat more slowly, which helps prevent overeating.

Seated leg curls are one of the best hamstrings exercises you can do.

Source: “Muscle Recruitment Pattern of The Hamstring Muscles in Hip Extension and Knee Flexion Exercises” published on March 31, 2020 in Journal of Human Kinetics.

There are two main ways to train your hamstrings: hip extension and knee flexion.

Exercises that involve moving your abdomen away from your thighs, such as the deadlift, Romanian deadlift, and glute bridge, train hip extension, and exercises that involve bringing your ankles closer to your butt, such as the seated and lying leg curl and nordic curl, train knee flexion.

So many choices . . . but which is best if you want big gams?

That’s the question scientists at Jobu University wanted to answer in this study.

The researchers had 7 untrained men do 4 workouts on 4 separate occasions, 3 days apart. In each workout, the weightlifters did 1 of 4 exercises:

- Lying leg curl

- Seated leg curl

- Donkey kick with the knee bent at 90 degrees

- Donkey kick with a straight leg

In each workout, the weightlifters did 2 sets: 1 set of 3 reps and 1 set of 30 reps.

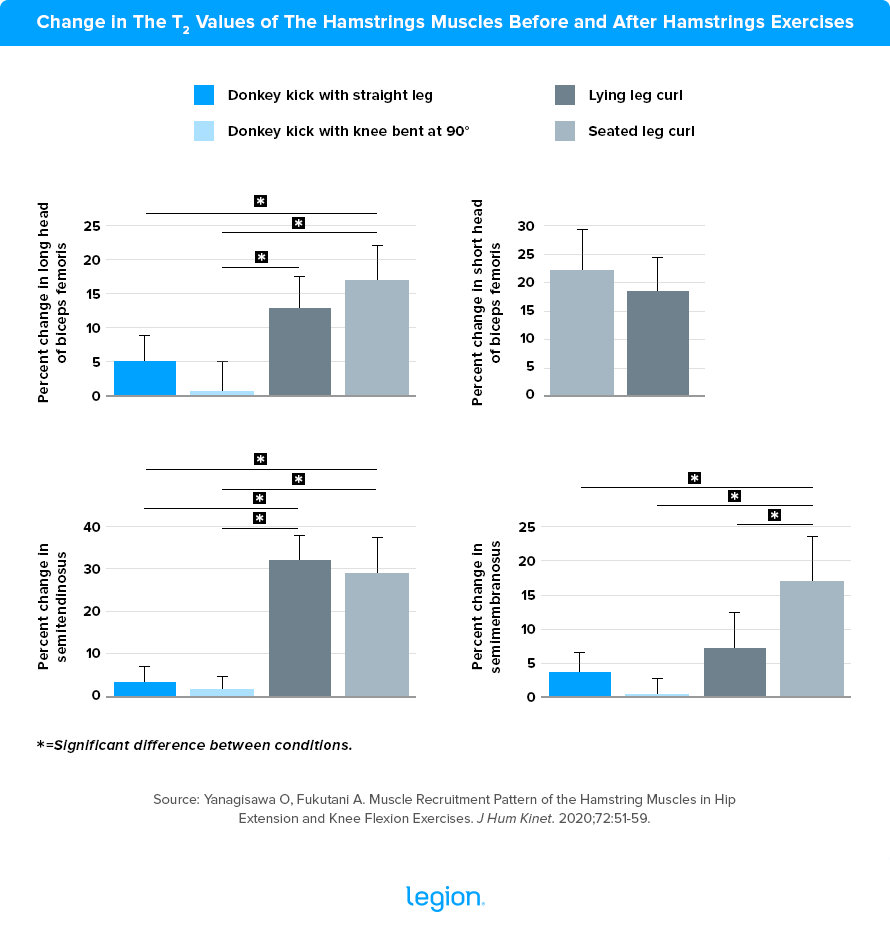

The results showed that the leg curl variations trained the hamstrings more than the donkey kick variations and that the weightlifters could generate more force and activate more muscle on the seated leg curl than the lying leg curl.

In other words, the seated leg curl was the most effective exercise for training the hamstrings, even more so than the lying leg curl. Here’s a graph illustrating the differences:

The researchers believed this was because the seated hamstring curl trains your hamstrings through a full range of motion (ROM) when fully stretched, which tends to be better for muscle growth.

In comparison, lying leg curls train your hamstrings through a full ROM but not when fully stretched, and exercises like deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, and good mornings train your hamstring when stretched but not through a full ROM.

Cool cool cool, but does this mean the seated hamstring exercise is the only exercise you should do for your hammies?

Not necessarily.

Compound exercises that allow you to lift heavy weights and effectively implement progressive overload should always be the nucleus of a well-designed lower-body workout. That’s why they take precedence in my programs for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

However, based on the results of this study and others like it, it’s probably sensible to choose the seated hamstring curl as your go-to hamstring accessory exercise most of the time.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about what exercises to include in your training program to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

TL;DR: The seated leg curl is one of the most effective exercises for developing your hamstrings.

Using a massage gun before training makes you more flexible.

Source: “The Acute Effects of a Percussive Massage Treatment with a Hypervolt Device on Plantar Flexor Muscles’ Range of Motion and Performance” published on December 10, 2018 in Journal of International Medical Research.

Massage guns have become increasingly popular as a post-workout recovery gadget in the past few years.

Even more recently, massage gun manufacturers have begun claiming that they’re the perfect pre-workout tool, too, capable of loosening up tight muscles and increasing your flexibility without hindering your performance.

Is this accurate or marketing bunkum?

To find out, scientists at the University of Graz invited 16 recreational athletes to participate in two tests. In both, they strapped the athletes’ ankles to an isokinetic dynamometer, a machine that tests a joint’s range of motion (ROM) and strength.

The difference was that in one test, the researchers massaged the calf of the tethered leg using a massage gun for 5 minutes and in the other, they didn’t (this acted as the “control condition”).

The results showed that in the control condition, the athletes experienced no changes in flexibility or strength after sitting with their feet in an isokinetic dynamometer. No surprises there.

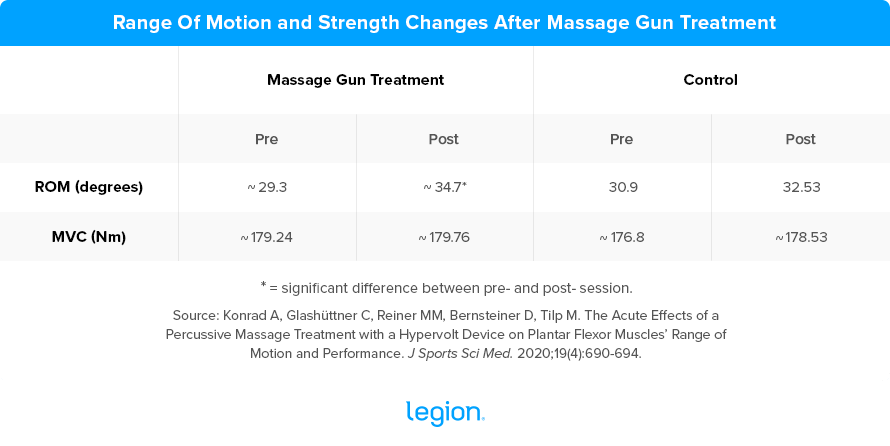

After the massage, however, the athletes’ ankle ROM increased by ~5.4 degrees without losing strength (measured using maximum voluntary contraction in newton meters, or Nm). Here’s a table of the results:

It’s not exactly clear how massage guns increase ROM, though it’s likely due to two factors:

- Massage guns put pressure on your muscles, skin, and fascia, which may alter the viscosity of the fluid in these areas, allowing you to move more freely.

- Massage guns may decrease pain perception, allowing you to stretch further without discomfort.

Regardless of the mechanism, the important thing is that these results and those of a similar study show that massaging your muscle with a massage gun before exercising increases your flexibility without thwarting your performance.

This is important because many people stretch before training, which may help you feel looser, but also likely makes you perform worse. Thus, using a massage gun is a viable alternative to stretching that provides all the benefits, without the demerits.

Let me add a rider to these results: While the study showed that massage guns increase flexibility, they didn’t show this actually improved performance, reduced the risk of injury, improved exercise technique, or really did anything useful. Thus, it’s not evidence that flexibility is inherently good, but if inflexibility happens to be an issue for you (perhaps tight shoulders makes it difficult to bring the bar to your chest while bench pressing, for instance), a little massage gunnery might be helpful.

TL;DR: Using a massage gun to massage a muscle for 5 minutes before training makes you more flexible without reducing your performance.

Scientific References +

- Teo, P. S., Lim, A. J. Y., Goh, A. T., Janani, R., Choy, J. Y. M., McCrickerd, K., & Forde, C. G. (2022). Texture-based differences in eating rate influence energy intake for minimally processed and ultra-processed meals. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 116(1), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC068

- Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., Cai, H., Cassimatis, T., Chen, K. Y., Chung, S. T., Costa, E., Courville, A., Darcey, V., Fletcher, L. A., Forde, C. G., Gharib, A. M., Guo, J., Howard, R., Joseph, P. V., McGehee, S., Ouwerkerk, R., Raisinger, K., … Zhou, M. (2019). Erratum: Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake (Cell Metabolism (2019) 30(1) (67–77.e3), (S1550413119302487), (10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008)). Cell Metabolism, 30(1), 226. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CMET.2019.05.020

- Hawton, K., Ferriday, D., Rogers, P., Toner, P., Brooks, J., Holly, J., Biernacka, K., Hamilton-Shield, J., & Hinton, E. (2019). Slow Down: Behavioural and Physiological Effects of Reducing Eating Rate. Nutrients, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU11010050

- Teo, P. S., Lim, A. J. Y., Goh, A. T., Janani, R., Choy, J. Y. M., McCrickerd, K., & Forde, C. G. (2022). Texture-based differences in eating rate influence energy intake for minimally processed and ultra-processed meals. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 116(1), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/NQAC068

- Robinson, E., Almiron-Roig, E., Rutters, F., De Graaf, C., Forde, C. G., Smith, C. T., Nolan, S. J., & Jebb, S. A. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effect of eating rate on energy intake and hunger. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(1), 123–151. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.113.081745

- Li, J., Zhang, N., Hu, L., Li, Z., Li, R., Li, C., & Wang, S. (2011). Improvement in chewing activity reduces energy intake in one meal and modulates plasma gut hormone concentrations in obese and lean young Chinese men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(3), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.111.015164

- Smit, H. J., Kemsley, E. K., Tapp, H. S., & Henry, C. J. K. (2011). Does prolonged chewing reduce food intake? Fletcherism revisited. Appetite, 57(1), 295–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2011.02.003

- Forde, C. G. (2018). From perception to ingestion; the role of sensory properties in energy selection, eating behaviour and food intake. Food Quality and Preference, 66, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FOODQUAL.2018.01.010

- Yanagisawa, O., & Fukutani, A. (2020). Muscle Recruitment Pattern of the Hamstring Muscles in Hip Extension and Knee Flexion Exercises. Journal of Human Kinetics, 72(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.2478/HUKIN-2019-0124

- Schoenfeld, B. J., & Grgic, J. (2020). Effects of range of motion on muscle development during resistance training interventions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 2050312120901559. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901559

- Bloomquist, K., Langberg, H., Karlsen, S., Madsgaard, S., Boesen, M., & Raastad, T. (2013). Effect of range of motion in heavy load squatting on muscle and tendon adaptations. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(8), 2133–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-013-2642-7

- McMahon, G. E., Morse, C. I., Burden, A., Winwood, K., & Onambélé, G. L. (2014). Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E318297143A

- Kubo, K., Ikebukuro, T., & Yata, H. (2019). Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(9), 1933–1942. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-019-04181-Y

- Oranchuk, D. J., Storey, A. G., Nelson, A. R., & Cronin, J. B. (2019). Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 29(4), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.13375

- Maeo, S., Huang, M., Wu, Y., Sakurai, H., Kusagawa, Y., Sugiyama, T., Kanehisa, H., & Isaka, T. (2021). Greater Hamstrings Muscle Hypertrophy but Similar Damage Protection after Training at Long versus Short Muscle Lengths. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 53(4), 825–837. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002523

- Konrad, A., Glashüttner, C., Reiner, M. M., Bernsteiner, D., & Tilp, M. (2020). The Acute Effects of a Percussive Massage Treatment with a Hypervolt Device on Plantar Flexor Muscles’ Range of Motion and Performance. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 19(4), 690. /pmc/articles/PMC7675623/

- Behm, D. G. (2018). The Science and Physiology of Flexibility and Stretching. The Science and Physiology of Flexibility and Stretching. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315110745

- Behm, D. G., & Wilke, J. (2019). Do Self-Myofascial Release Devices Release Myofascia? Rolling Mechanisms: A Narrative Review. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 49(8), 1173–1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-019-01149-Y

- Cheatham, S. W., Stull, K. R., & Kolber, M. J. (2019). Comparison of a Vibration Roller and a Nonvibration Roller Intervention on Knee Range of Motion and Pressure Pain Threshold: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 28(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSR.2017-0164

- Veqar, Z., & Imtiyaz, S. (2014). Vibration Therapy in Management of Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS). Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research : JCDR, 8(6). https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/7323.4434

- Kujala, R., Davis, C., & Young, L. (2019). THE EFFECT OF HANDHELD PERCUSSION TREATMENT ON VERTICAL JUMP HEIGHT. International Journal of Exercise Science: Conference Proceedings, 8(7). https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijesab/vol8/iss7/75

- Damasceno, M. V., Duarte, M., Pasqua, L. A., Lima-Silva, A. E., MacIntosh, B. R., & Bertuzzi, R. (2014). Static stretching alters neuromuscular function and pacing strategy, but not performance during a 3-km running time-trial. PloS One, 9(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0099238

- Marek, S. M., Cramer, J. T., Fincher, A. L., Massey, L. L., Dangelmaier, S. M., Purkayastha, S., Fitz, K. A., & Culbertson, J. Y. (2005). Acute Effects of Static and Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation Stretching on Muscle Strength and Power Output. Journal of Athletic Training, 40(2), 94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0162-0908(08)70360-x

- Fletcher, I. M., & Anness, R. (2007). The acute effects of combined static and dynamic stretch protocols on fifty-meter sprint performance in track-and-field athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(3), 784–787. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-19475.1

- Rubini, E. C., Costa, A. L. L., & Gomes, P. S. C. (2007). The effects of stretching on strength performance. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 37(3), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737030-00003