Put some weight in a backpack.

Put on the backpack.

Walk.

That’s rucking in a nutshell.

While rucking is simple, it’s also one of the most underrated kinds of cardio you can do:

- It burns a boatload of calories

- It boosts your cardiovascular fitness

- It’s easy to recover from

- It’s versatile (you can do it anywhere)

- And, it’s social—you can easily do it with a group

What’s more, it’s also very easy to progressively overload your workouts. That is, you can continually make your rucks a little bit harder, which isn’t easy with walking.

In other words, rucking is one of the best kinds of cardio for people who “don’t like” cardio.

What Is Rucking?

Rucking is simply walking with a weighted backpack. That’s it.

The term “ruck” is short for “rucksack,” which is a durable backpack designed to carry heavy loads. Typically, rucksacks are made of more durable materials and feature thicker shoulder straps and back padding than regular backpacks, but the terms are often used interchangeably.

What’s the difference between rucking and hiking or backpacking, you wonder?

In the case of rucking, you’re carrying extra weight with the goal of getting a better workout. Typically, this extra weight is in the form of metal plates (ruck weights), bricks, sandbags, water jugs, or some other heavy object.

In the case of backpacking or hiking, you’re usually carrying extra weight because it’s needed to complete the trip (such as food, water, tent, etc.). The extra weight is incidental to your main goal, not the goal itself.

The History of Rucking

While the term “rucking” has come into vogue recently, humans have been humping heavy loads ever since our ancestors started walking upright.

That said, due to soldiers’ need to carry large amounts of food, weapons, and other supplies long distances, the history of rucking has been closely intertwined with military life for millennia. As the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus once remarked, “for what can you expect in a war, from a man who is not able to walk?”

In 107 BC, the statesman and general Gaius Marius reformed the Roman military, requiring legionaries to carry their own equipment on campaign, which worked out to about 50 to 60 pounds of armor, clothes, weapons, food, and other supplies. Previously, soldiers had stowed much of their kit on pack animals, which were slow, unwieldy, and inefficient.

Marius’ insistence on his soldiers rucking not only allowed Roman armies to move faster and cheaper, it also made the soldiers tougher, fitter, better warriors. Many of the soldiers took pride in their ability to haul their own supplies, and jokingly referred to themselves as muli mariani—“Marian Mules.”

As the ancient historian Plutarch explains:

“Setting out on the expedition, he [Marius] laboured to perfect his army as it went along, practising the men in all kinds of running and in long marches, and compelling them to carry their own baggage and to prepare their own food.”

Over two millennia later, rucking is still a key pillar of military training around the world. As Eric Haney details in his book Inside Delta Force, candidates for Delta Force (one of the most elite units in the U.S. Military) are required to march with a 45-pound rucksack for up to 50 miles over rough terrain in order to qualify for this elite unit. Navy SEALs, Green Berets, and most other elite military teams have similar rucking standards.

Ironically, modern soldiers often have to carry much more weight than their chainmail-clad counterparts two thousand years ago.

While advanced military technologies like radios, body armor, guns, ammunition, and medical equipment have made soldiers more effective, these gadgets also weigh a lot. For instance, U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan were often required to ruck up to 130 pounds over mountainous terrain during long patrols.

Rucking Benefits

Rucking Burns a Lot of Calories

It may surprise you to learn that walking (without a heavy backpack) burns almost as many calories as a slow run.

For instance, a study conducted by scientists at California State University found that subjects burned about 350 calories per hour while walking at a 4-mile-per-hour pace (a brisk walk).

As you’d expect, you burn a lot more calories when you add 20, 30, or more pounds to your back.

Specifically, a study on military personnel conducted by NATO found that you can expect to burn around 600 calories per hour when rucking 45 pounds at about 4 miles per hour on a flat road.

In the late 70s, military researchers even came up with an equation to accurately estimate how many calories you burn while rucking with different weights at various speeds and gradients. It’s known as the Pandolf equation, and it looks like this:

M = 1.5 W + 2.0 (W + L)(L/W)2 + n(W + L)(1.5V2 + 0.35VG)

Translation:

The more weight you carry, the faster you walk, and the steeper or rougher the terrain you walk on, the more calories you’ll burn rucking.

For example, I weigh 170 pounds and usually ruck with a 45-pound pack at about 4 miles per hour over moderately hilly terrain (let’s call it a 2% grade).

Based on those numbers, I’m burning around 700 calories per hour rucking—about twice as many calories as I’d burn walking and almost as many as I’d burn during a moderate bike ride or run.

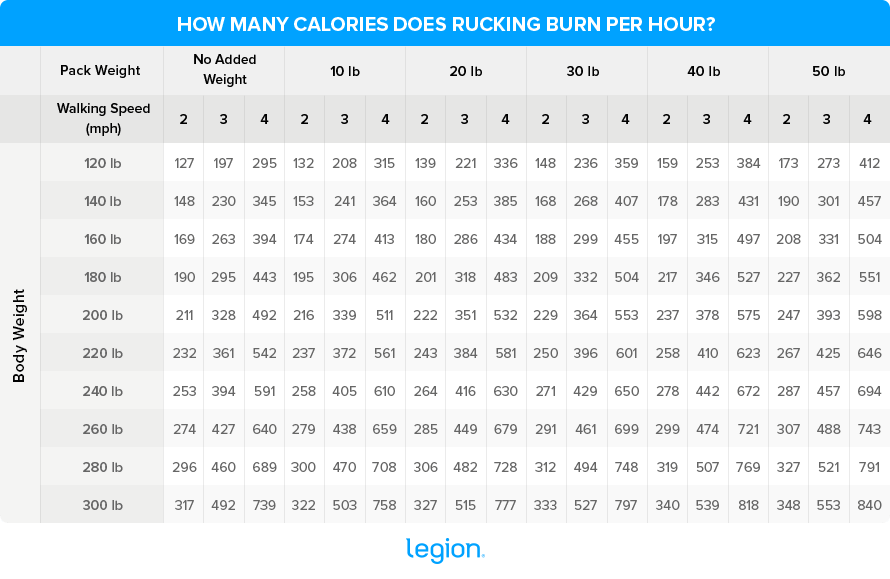

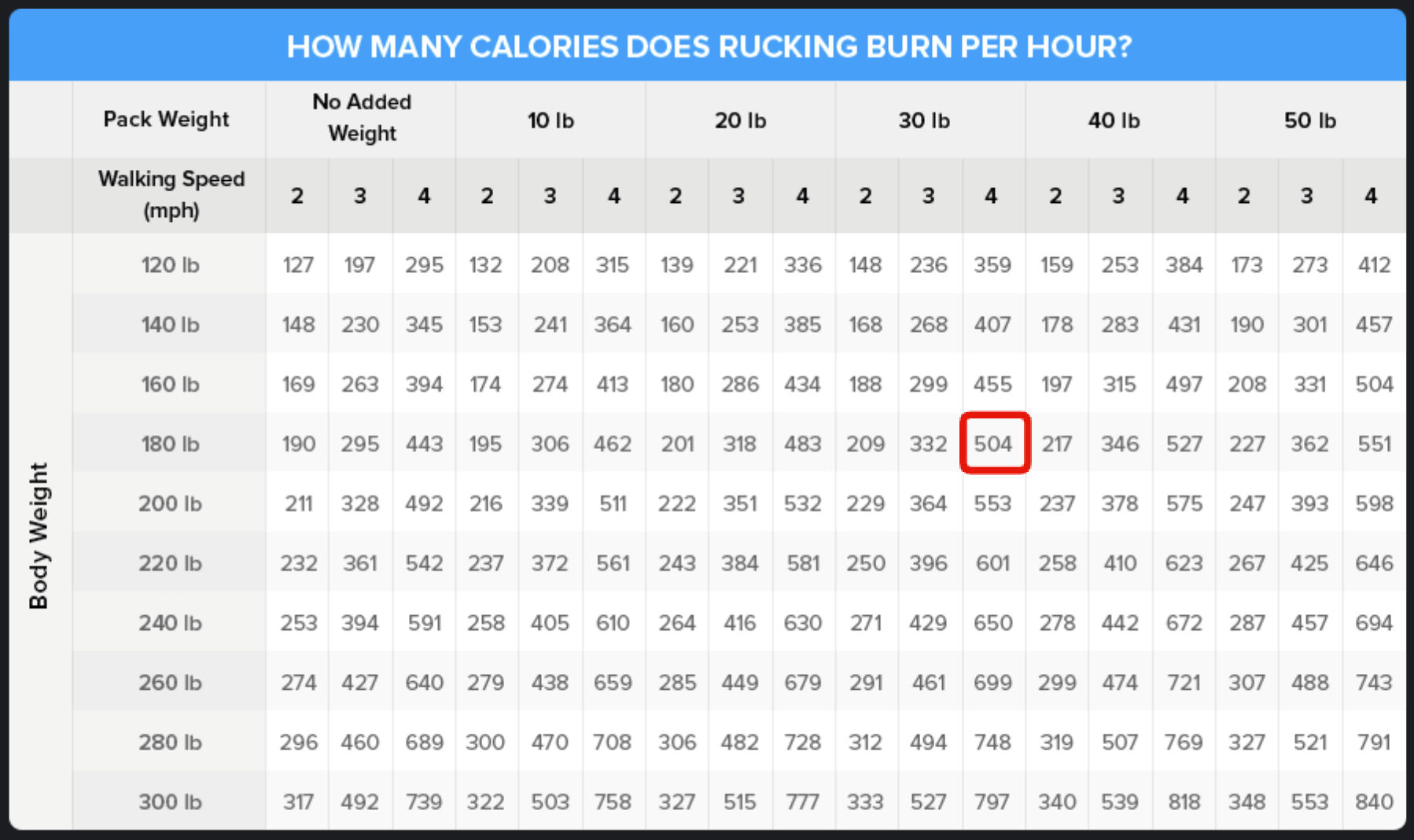

You can use the following chart to estimate how many calories you’d burn carrying different weights at different speeds.

First, find the amount of weight you’re carrying in the top row and the speed you’re walking with that weight in the next row down. Then, find your body weight in the left hand column. Trace the row containing your body weight to the right until it intersects with the vertical row containing your rucking weight and speed.

That’s roughly how many calories you can expect to burn rucking.

For example, here’s how many calories a 180-pound man would burn in one hour rucking 30 pounds at 4 miles per hour:

Rucking Boosts Your Fitness More Than Walking

While walking is an excellent form of cardio, it isn’t nearly as effective for improving fitness as rucking.

Why?

For the same reason that bench pressing is more effective than doing push-ups for building muscle—it helps you better implement progressive overload.

Compared to walking, rucking elevates your heart rate higher, burns more fat, and provides an overall greater “training effect” in the same amount of time.

Rucking Is Easier on the Body Than Running

Rucking is probably less stressful on the body than running, though not for the reasons most people think.

You’ll often hear that rucking is lower impact than running, but research shows both activities are comparable in this regard.

For example, a study on military recruits found that rucking with 45 pounds on a flat surface creates maximum impact forces of around twice the person’s body weight. That is, if a person weighs 200 pounds, the maximum amount of force transmitted through their legs while rucking would be around 400 pounds.

Studies on running show that peak impact forces are around 1.5 to 3 times body weight—not drastically different from rucking. What’s more, research shows peak impact forces during running aren’t correlated with injuries, so it’s probably not worth overly worrying about anyway.

So, why is rucking easier on your body than running?

I’m not aware of any studies that have compared running and rucking in this manner, but based on my own experience rucking and running and talking with others who do as well, it seems that rucking causes much less muscle damage than running. This is also why rucking also tends to interfere with weightlifting workouts less than running—you don’t feel as stiff, sore, and drained after a long ruck as you do after a long run.

That said, rucking is still harder on your body than walking, which is why it’s important not to do too much too quickly. (More on this below).

Rucking (Probably) Doesn’t Interfere with Muscle Growth

You’ve probably heard that cardio can interfere with muscle growth, and this is true.

What’s also true, though, is that not all forms of cardio are equally detrimental.

For example, running clearly impairs muscle and strength gains but cycling and rowing don’t seem to. The amount of cardio you do also makes a difference (even short runs don’t seem to cause problems, but longer ones do).

The main reason for this is that cycling and rowing cause very little muscle damage compared to running, and the same thing is true of rucking.

If you decide to try your hand at rucking you’ll experience this for yourself. You can often go on a long ruck on a Sunday, for example, and still do a heavy leg workout on Monday without missing a beat.

This doesn’t mean you can do as much rucking as you want without interfering with your progress in the gym (a 5 hour ruck will still take some starch out of you), but it’s unlikely to interfere with your ability to gain muscle if you do it a few hours per week.

In other words, you can think of moderate amounts of rucking as a “penalty free” way to burn calories and boost your fitness.

Rucking Is Versatile

My favorite form of cardio is cycling for a variety of reasons (lack of interference with weightlifting, high calorie expenditure, immersion in nature, etc.), but it also presents a few logistical problems: if you have a road bike, you need paved roads; it becomes difficult if not impossible if the weather is bad; and indoor cycling is painfully boring.

The same problem is true of other forms of cardio that require specialized exercise equipment: if you don’t have a rowing machine, stairmaster, elliptical, etc., then you can’t do your workout.

That isn’t the case with rucking.

So long as you have a backpack, some weights, and a place to walk, you can ruck. And depending on your mettle (or masochism), you can ruck in any weather conditions—rain, sleet, or snow.

Rucking Is Social

Most kinds of cardio don’t lend themselves to conversation and camaraderie.

Unless you’re moving at a snail’s pace, talking while cycling, running, or rowing is frequently frustrating and unsafe. Even if you like to do cardio indoors on a machine, it’s often impossible to chit chat over the noise of the machines.

Rucking is different.

It’s quiet, relatively slow, and very safe, which makes it easy to chew the fat with friends. Although you’ll be breathing hard if you’re rucking at a fast pace with a heavy pack, you can still communicate without having to scream over a rowing machine or worrying about getting poleaxed by a careless driver.

How to Start Rucking

Step 1: Walk Before You Ruck

If you aren’t currently walking regularly, spend at least two weeks walking before you try rucking.

Increase the pace and duration of your walks until you’re doing at least two hours of walking per week, with each walk lasting at least 30 minutes.

Do this even if you’re already active with other sports (like weightlifting, cycling, basketball, etc.), as it will prepare your joints, tendons, and muscles for the specific challenges of rucking and reduce your risk of injury.

If you’re very overweight (30+% body fat in men and 35+% in women), stick to walking until you reach a healthier body fat percentage (<25% body fat for men and <30% for women). When you’re overweight, you’re already “rucking” a considerable amount of extra mass in the form of excess body fat, so adding more is unnecessary and increases your risk of injury.

Step 2: Buy a Good Rucksack and Buy (or Make) Ruck Weights

When you first start rucking, you shouldn’t be using much weight or walking that far, and thus any backpack will fit the bill. I started rucking by putting two water jugs inside an old backpack, for instance.

When you start rucking heavier weights for longer distances, though, you’ll want a real rucksack and better weights.

A good rule of thumb is that if you’re carrying more than 30 pounds for over 1 hour, it’s worth investing in a real rucksack. Generally, these will be made of stronger materials and feature thicker padding, making your rucks much more comfortable and ensuring your bag doesn’t fall apart.

Some good options:

- Best Overall Rucksack: GoRuck GR1 ($325)

- Best Value Rucksack: 5.11 RUSH12 Tactical Military Backpack ($115)

- Best Rucksack with Hydration: Camelbak HAWG Rucksack ($170)

- Best Rucksack for Hiking and Rucking: Osprey Mutant 38 L ($170)

If you get really into rucking and plan on carrying more than 30 pounds for several hours or more, you’ll want to invest in a rucksack that features a hip belt and rigid frame. These two features help transfer the weight on your back to your hips, which is significantly more comfortable and more efficient than just using shoulder straps to support the load.

These packs tend to be pretty expensive, so don’t buy one unless you plan on rucking consistently (that said, they’re also great for backpacking and other outdoor activities and will last a lifetime).

Some good options:

- Mystery Ranch Terraframe ($350) or Pintler ($450)

- Kifaru Kutthroat ($447)

- Stone Glacier EVO 3300 ($604)

In terms of weights, you can use any heavy object, but ruck weights work best. These are rectangular steel or iron plates of various weights that fit comfortably into most backpacks and evenly distribute the weight across your back.

I recommend you start with a ruck weight that weighs 20 pounds.

You can also make a ruck weight by filling bags with sand or bricks, but these aren’t as comfortable or dense as metal ruck weights. Thus, they aren’t well-suited for long rucks and take up a lot of space in your pack. Water jugs also work well when you’re new to rucking and not carrying much weight, but you’ll soon want to upgrade to ruck weights.

Here are some good options for ruck weights:

- Yes4All Cast Iron Ruck Weights ($45 for a 20 lb. plate)

- GoRuck Ruck Plates ($99 for a 20 lb. plate)

If you live in Europe, you also can buy very high quality adjustable ruck weights from a Swedish company called Tomahawk Designs (the website doesn’t say anything about ruck weights, but shoot them an email and they’ll help you out). They’re expensive, but also modular, allowing you to adjust the ruck weight from 10 to 40 pounds.

Step 3: Start Rucking

Start with 20 pounds, which will be about 10 to 20% of body weight for most people.

Aim to do at least three, 30-minute rucks per week to start. You can maintain whatever pace you like, but try to work your way up to 20 minutes per mile to start (3 miles per hour).

Once you can do that, you have a few options in terms of how to progress

- You can walk faster

- You can walk further

- You can ruck a heavier weight

I recommend you progress in that order—first increasing your pace over the same distance, then increasing the distance of your rucks, then carrying a heavier weight.

The reason for this is that increasing the weight in your pack quickly becomes uncomfortable and awkward and requires the use of a sturdier, higher-quality pack (like those listed above), whereas you can quickly and easily increase the pace and duration of your rucks.

Here’s a good system for progressing your ruck workouts:

Beginner Ruck Workout

Ruck weight: 20 pounds

Duration: 30 minutes

Pace: 20 minutes per mile (3 miles per hour)

Frequency: 3 times per week

Intermediate Ruck Workout

Ruck weight: 30 pounds

Duration: 45 minutes

Pace: 15 minutes per mile (4 miles per hour)

Frequency: 3 times per week

Advanced Ruck Workout

Ruck weight: 45 pounds

Duration: 1 hour

Pace: 15 minutes per mile (4 miles per hour)

Frequency: 2 times per week, plus one 90-minute ruck at the same pace with the same weight (most people like to do this on the weekends)

FAQ #1: What kind of shoes should you wear?

Whatever you have on hand (er, feet) that’s comfortable. You don’t need boots.

If you enjoy rucking and want to invest in a good pair of shoes, a pair of trail running shoes tends to work best. I like the Salomon XA Pro 3D model.

Since rucking is closely associated with soldiers, and soldiers wear boots, many people assume that boots are best for rucking. This is wrong.

First, adding extra weight to your feet is disproportionately fatiguing compared to wearing weight on your back. Specifically, research shows that every pound added to your feet costs about five times more energy than a pound added to your pack.

Second, while many advocates of boots claim they protect you from rolling your ankles, this is only a concern if you’re walking over very rough terrain (like sharp, loose rocks or snow). The only other reason to wear boots is to keep your feet dry and warm in bad weather conditions.

The rest of the time, wear athletic or running shoes.

FAQ #2: How should you plan your ruck workouts around weightlifting?

Although rucking doesn’t usually interfere with your weightlifting workouts or ability to gain muscle, it can if you do too much or at the wrong times. Thus, it’s worth taking a few simple steps to minimize this “interference effect” from rucking.

Here’s how:

- Limit the time you spend rucking to no more than the amount of time you spend weightlifting each week. If you lift weights for five hours per week, don’t ruck for more than five hours per week.

- Limit most of your rucks to no more than 1 hour per session, and only do 1 long ruck (more than one hour) per week.

- Do your rucks and weightlifting on separate days if possible, and if you have to do them on the same day, try to separate them by at least six hours.

- When lifting weights and rucking on the same day, do your weightlifting first, and try to schedule your rucks on the days you train your upper body.

- Don’t run with a rucksack. Not only does it increase your risk of injury, it’s awkward and more likely to interfere with your weightlifting workouts.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about how to schedule your workouts, how often you should train, and what exercises you should do to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

FAQ #3: How can I make rucking more comfortable?

First, practice.

Like any new activity, rucking can feel uncomfortable for the first week or two. Keep at it, though, and follow the guidelines in this article, and you’ll soon get used to it.

Second, if you’re still experiencing discomfort while rucking, invest in a good rucksack and real ruck weights (not bricks, sandbags, or water jugs) like those listed earlier in this article.

Third, if you want to carry really heavy loads (30+ pounds) for longer distances, invest in a backpack that features a hip belt and rigid frame, like those listed earlier in this article.

FAQ #4: Can I wear a weighted vest instead?

Sure!

Just keep in mind these generally aren’t designed to carry as much weight as a rucksack, they make it more difficult to breathe, and they don’t allow you to carry anything else (like water, snacks, sunglasses, etc.), which makes them less practical than a rucksack.

Scientific References +

- Jones, B. H., Toner, M. M., Daniels, W. L., & Knapik, J. J. (1984). The energy cost and heart-rate response of trained and untrained subjects walking and running in shoes and boots. Ergonomics, 27(8), 895–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140138408963563

- Pigman, J., Sullivan, W., Leigh, S., & Hosick, P. A. (2017). The Effect of a Backpack Hip Strap on Energy Expenditure While Walking. Human Factors, 59(8), 1214–1221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720817730179

- Bell, G. J., Petersen, S. R., Wessel, J., Bagnall, K., & Quinney, H. A. (1991). Physiological adaptations to concurrent endurance training and low velocity resistance training. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 12(4), 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1024699

- Wilson, J. M., Marin, P. J., Rhea, M. R., Wilson, S. M. C., Loenneke, J. P., & Anderson, J. C. (2012). Concurrent training: A meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(8), 2293–2307. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31823a3e2d

- Stefanyshyn, D., Stergiou, P., Nigg, B., & Lun, V. (n.d.). The relationship between impact forces and running injuries | Request PDF. Retrieved March 10, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295484867_The_relationship_between_impact_forces_and_running_injuries

- Baltich, J., Maurer, C., & Nigg, B. M. (2015). Increased vertical impact forces and altered running mechanics with softer midsole shoes. PLoS ONE, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125196

- Earl-Boehm, J. E., Poel, D. N., Zalewski, K., & Ebersole, K. T. (2020). The effects of military style ruck marching on lower extremity loading and muscular, physiological and perceived exertion in ROTC cadets. Ergonomics, 63(5), 629–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2020.1745900

- Pandolf, K. B., Givoni, B., & Goldman, R. F. (1977). Predicting energy expenditure with loads while standing or walking very slowly. Journal of Applied Physiology Respiratory Environmental and Exercise Physiology, 43(4), 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1977.43.4.577

- Wilkin, L. D., Cheryl, A., & Haddock, B. L. (2012). Energy expenditure comparison between walking and running in average fitness individuals. In Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Vol. 26, Issue 4, pp. 1039–1044). J Strength Cond Res. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822e592c

- Wright, M. (n.d.). Digital Commons@WOU Marius’ Mules: Paving the Path to Power. Retrieved March 10, 2021, from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his