When you start lifting weights, your main priority should be to get stronger, but you shouldn’t worry about how your strength compares to others.

As you become more advanced, though, one of the best ways to keep yourself motivated is to set strength targets.

To do this effectively, you need to know how much weight you should be able to lift on a given exercise for your weight and experience level.

And this is where strength standards can be helpful.

Strength standards are strength benchmarks for different exercises based on what other weightlifters with similar characteristics can achieve, and they’re useful because they . . .

- Give you targets to aim for that are challenging but reasonable

- Help you understand your strengths and weaknesses

- Help you see how much progress you’ve made since you began lifting weights

In this article, you’ll learn everything you need to know about strength standards, including what strength standards are and how they’re calculated, how to use the best strength standards for men and women to set strength goals, how to get as strong as possible, and more.

Key Takeaways

- Strength standards help you set realistic, motivating strength goals based on your body weight, sex, and experience level.

- They’re useful for identifying your strengths and weaknesses, tracking progress, and staying focused as you get stronger.

- Powerlifting-based standards are common but often reflect elite performance, so most lifters benefit more from benchmarks based on natural, recreational lifters.

- The two most practical strength standards Tim Henriques’s and Mark Rippetoe’s standards are the most practical.

- Your anatomy and age can affect how strong you are, even if you have similar muscle mass to someone else.

- Following a structured strength training program and tracking progress over time is the best way to get stronger.

To increase your strength as quickly as possible, consider using a high-quality protein powder to help you reach your daily protein target, creatine to support recovery and muscle growth, and a pre-workout to enhance energy, focus, and performance.

Table of Contents

+

What Are Strength Standards?

Strength standards are strength benchmarks for different exercises based on your body weight and sex.

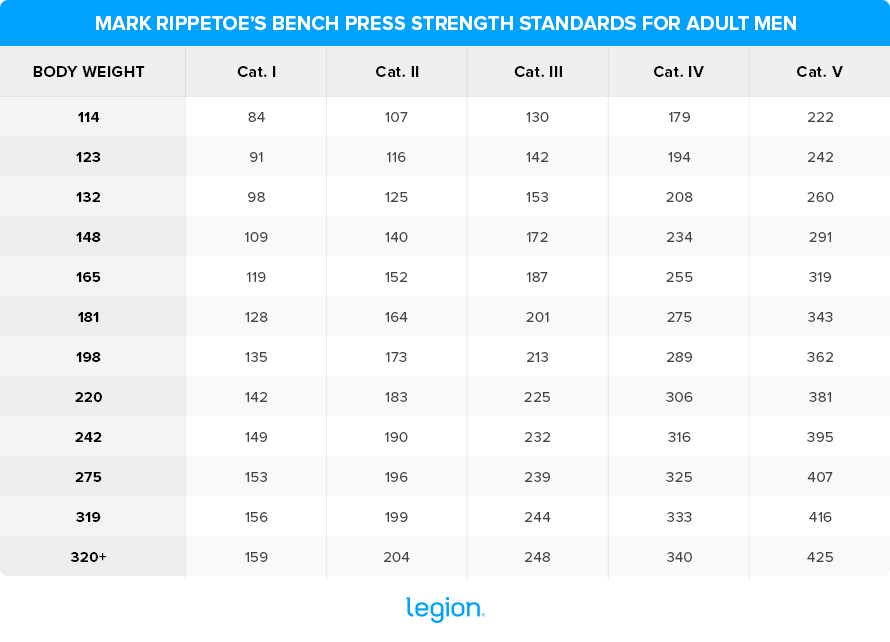

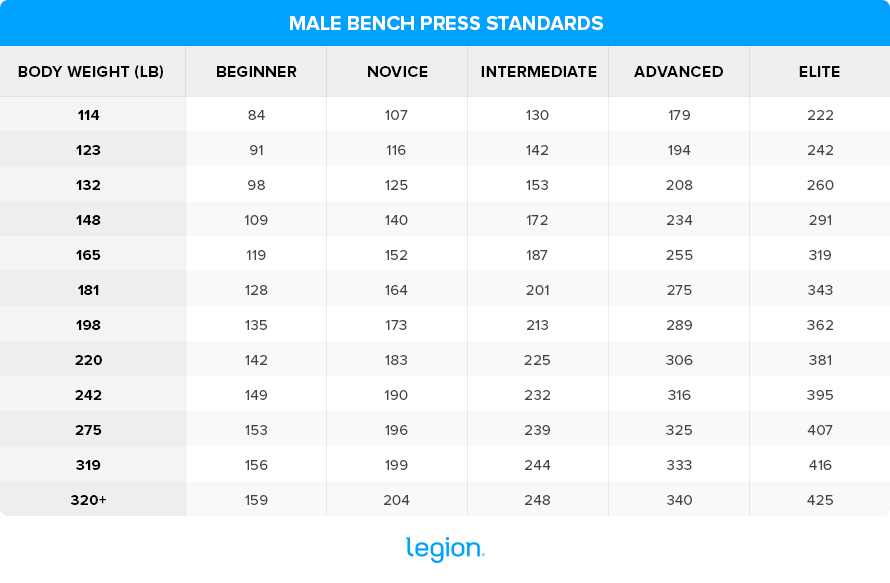

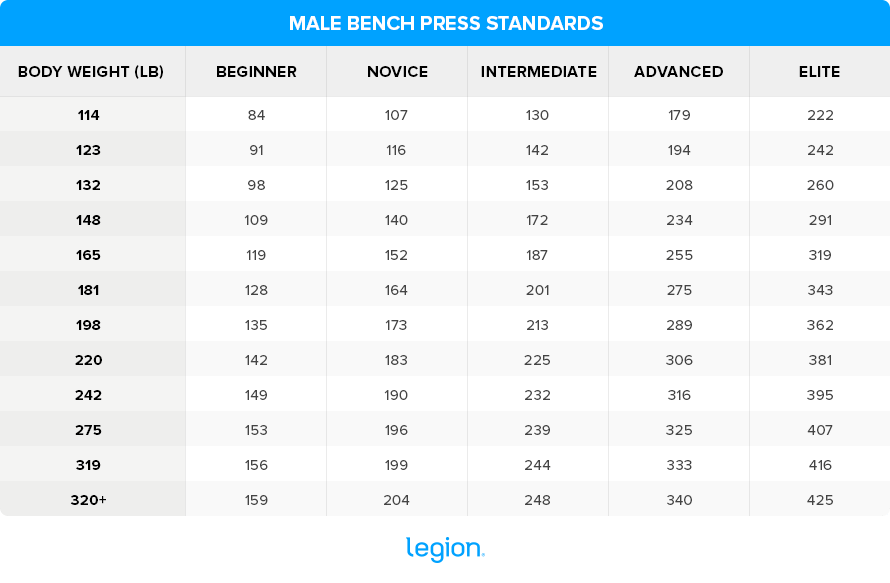

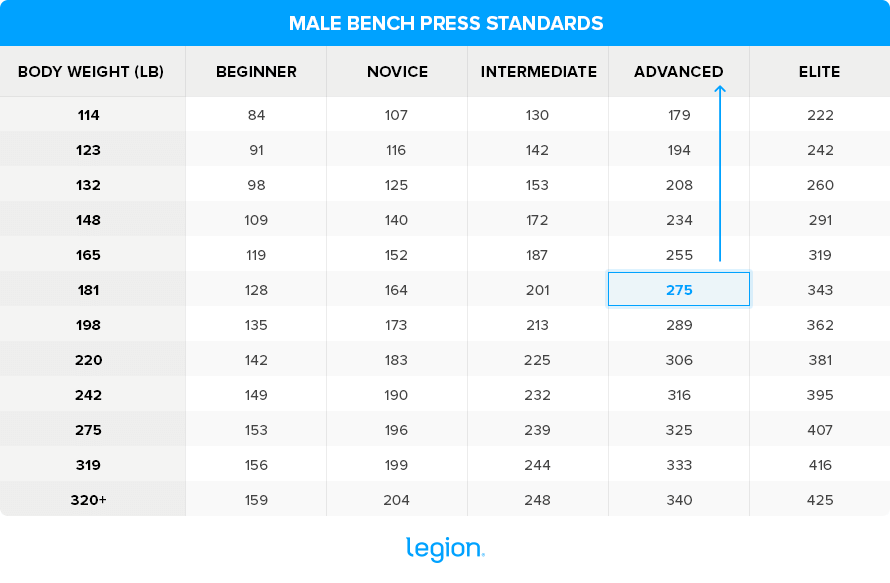

They’re often shown as tables, like Mark Rippetoe’s bench press strength standards here:

To figure out which category you belong in, you’d find your body weight in the left hand column and your one-rep max in the corresponding row (more on this soon).

Strength standards are also sometimes shown as multiples of body weight. This is the method Mike uses in his fitness book for intermediate weightlifters Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger when he talks about how strong you should be before you level up from Bigger Leaner Stronger.

Here’s how it looks:

- Squat Strength Standards: 1.5 times your body weight.

- Bench Strength Standards: 1.2 times your body weight.

- Deadlift Strength Standards: 2 times your body weight.

- Overhead Press Strength Standards: 0.8 x body weight.

- Chin-up or Pull-up Strength Standards: 8 reps with bodyweight or at least 1 rep with bodyweight plus 20 percent.

And in other cases, weightlifting strength standards are based on a “rep-max” instead of a one-rep max.

For instance, a common strength standard for the pull-up and chin-up is “10 x body weight,” which means you should aim to do 10 reps with your body weight (a 10-rep max).

Where Do Strength Standards Come From?

Originally, strength standards were created by powerlifting organizations to rank their competitors.

Powerlifting is a sport based on getting as strong as possible on the squat, bench, and deadlift, which are considered some of the best indicators of your whole-body strength.

Your “score” in powerlifting is the sum of your squat, bench press, and deadlift one-rep max, which is referred to as your “total.” If you squat 300, bench 200, and deadlift 400, then your total is 900 (300+200+400=900).

Other exercises like the overhead press, pull-up, front squat, and barbell row aren’t used in powerlifting, but many coaches have created strength standards for those based on what they’ve learned working with thousands of athletes.

(You can also find strength standards for exercises like the barbell curl, leg press, and skull crusher, although most people don’t set targets for these.)

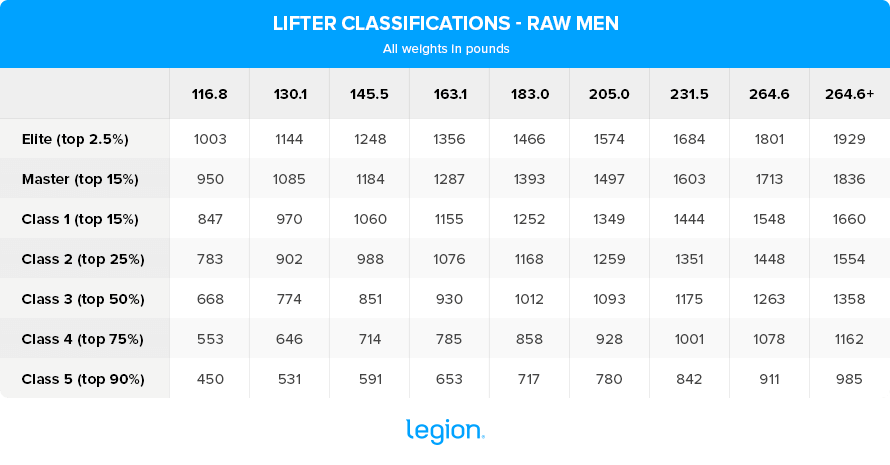

Powerlifting strength standards are created by looking at all of the totals of all lifters in a powerlifting federation, and then ranking them based on what percentage of lifters are able to achieve different totals.

Then, different categories are created based on these percentiles.

For example, here are the men’s strength standards for the United States of America Powerlifting (USAPL) federation:

These numbers are so high because they’re powerlifting totals.

“Elite” in this case means you’re in the top 2.5%—freaky strong. In other words, you’re stronger than 97.5% of the other people in this group, which is already made up of very strong powerlifters.

On the other end of the spectrum we have “Class 5,” which includes people who are only stronger than 10% of other lifters in the USAPL.

That still means you’re stronger than most recreational weightlifters, but you’re at the bottom of the totem pole in this powerlifting federation.

The numbers at the top of the table are body weights in pounds. The heaviest people are generally the strongest, so most strength standards are based on relative strength, or how much you can lift at a given body weight.

There’s a problem with relying on powerlifting strength standards, though:

They’re entirely based on data from people whose only goal is to squat, bench press, and deadlift as much as possible. Many of them will be genetically gifted for strength sports, and many will also use steroids to goose their numbers (the USAPL tests for drug use, but these tests aren’t difficult to cheat).

If you’re interested in powerlifting then by all means use strength standards for powerlifting. If you’re a recreational lifter who simply wants to be healthy, muscular, and strong (and natural), though, then I recommend you stick with strength standards that are based on data from lifters like you, which we’ll look at next.

The Best Strength Standards for Every Weightlifter

There are many different strength standards you can follow, but the two that I recommend are:

- Tim Henrique’s strength standards, which are based on multiples of your body weight and are simple to use.

- Mark Rippetoe’s strength standards, which classify lifters into five categories ranging from weakest to strongest and give exact targets for each classification and body weight.

Which you use comes down to personal preference, so to help you to decide which is better for you, let’s examine both.

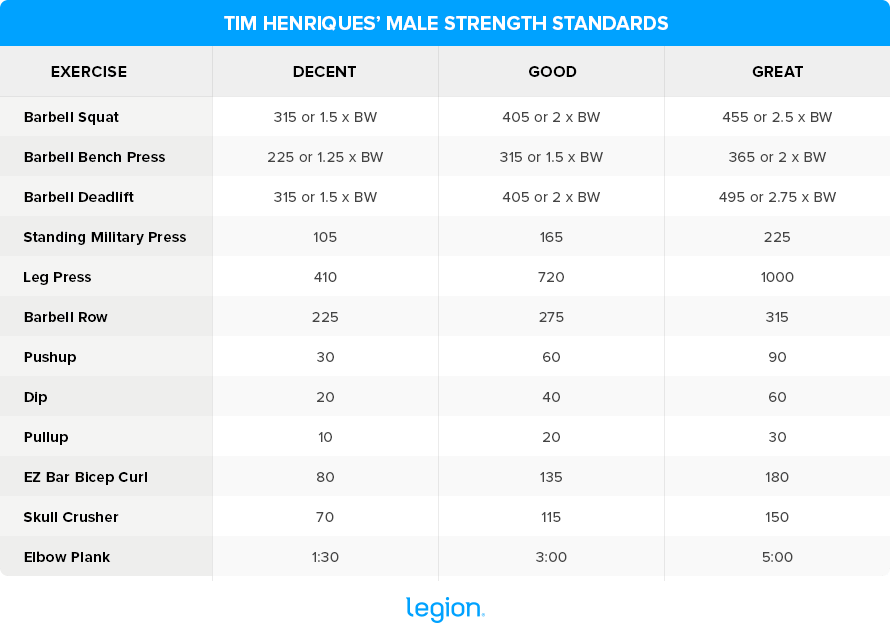

Tim Henrique’s Strength Standards

Tim Henriques is a powerlifter and powerlifting coach who’s worked with thousands of athletes and coaches over the past few decades. He’s also a writer and the author of All About Powerlifting, one of the best books on the topic to date.

He came up with these strength standards to give his athletes simple targets they could use in their training.

Henriques divides weightlifters into three categories:

- Decent: You should be able to achieve a Decent level of strength after around 6-to-12 months of consistent strength training.

Some genetically gifted people may be able to reach these standards without any strength training, but almost everyone should be able to reach them within a year.

If you’re Decent, you won’t be “strong” by weightlifting standards, but you won’t be “weak,” either.

- Good: You should be able to achieve a Good level of strength after around 1-to-3 years of consistent strength training.

Some genetically gifted people may be able to reach these standards within a year, but most will take closer to two-to-three years. Others may take up to 5-to-10 years if they’re dogged by long breaks from lifting, injuries, flagging motivation, and the like.

If you’re Good, you’re probably one of the stronger weightlifters at your gym, and much stronger than the average untrained person.

- Great: You may be able to achieve a Great level of strength after 5-to-10 or more years of consistent strength training.

If you have average or above average genetics for strength and muscle gain, a strong work ethic, and don’t get sidelined by injuries, overtraining, or other extended breaks from lifting, you likely can become a Great lifter.

If you have below average genetics, a lackluster worth ethic, and take many extended breaks from lifting, you’ll likely never become a Great lifter.

Keep in mind that Henriques defines Great relative to the average lifter. Although a 455 pound squat wouldn’t be considered “great” among many powerlifters, it’s jaw-droppingly strong to people in most gyms.

You’ll also notice that Henriques provides standards based on either an absolute weight or a multiple of your body weight. For example, a Good squat for a female would be 155 pounds or 1.25 x body weight.

Feel free to use either standard, as they’ll generally be close for most people of an average weight or height.

The reason he provides both options is there aren’t established standards for many exercises.

For instance, while it’s generally agreed upon that a 2.5 x bodyweight squat is a good benchmark for an advanced male weightlifter, there’s no such standard for an exercise like barbell rows or biceps curls.

In these cases, an absolute number makes more sense as a strength standard instead of a body weight multiplier.

Here are Tim Henriques’ male strength standards:

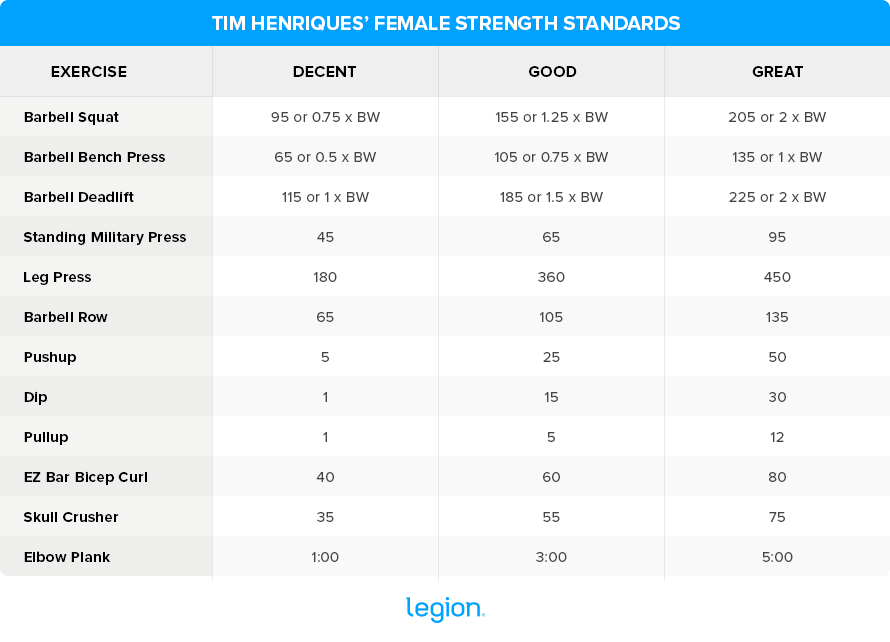

And here are Tim Henriques’ female strength standards:

Mark Rippetoe’s Strength Standards

Mark Rippetoe is a strength coach and writer, and as the author of Starting Strength and Practical Programming, has done more to popularize heavy barbell training than perhaps anyone else alive.

Rippetoe has worked with tens of thousands of weightlifters, weightlifting coaches, and athletes, and he used his extensive experience to create realistic, “natural” strength standards based on the performance of recreational weightlifters.

These standards (sometimes referred to as “Starting Strength standards”) have proven to be extremely accurate for most people over the years. They also have the advantage of including five categories instead of the three in Tim Henriques’ strength standards, which means you have more opportunities to “level up.”

That is, it might take several years to go from a Good to Great lifter in Henriques’ system, but it might only take 6-to-12 months to go from a Cat lll to Cat lV lifter in Rippetoe’s system.

Rippetoe divides weightlifters into five categories as follows:

- Cat l

- Cat ll

- Cat lll

- Cat lV

- Cat V

If we calibrate Rippetoe’s strength categories based on weightlifting experience, the result would look something like this:

- Cat l = Beginner (0-to-6 months of weightlifting experience)

- Cat ll = Novice (6-to-12 months of weightlifting experience)

- Cat lll = Intermediate (1-to-2 years of weightlifting experience)

- Cat lV = Advanced (3-to-4 years of weightlifting experience)

- Cat V = Elite (5+ years of weightlifting experience)

Technically, someone with good genetics could be a Cat lll weightlifter even if they’re just starting out, and someone with poor genetics, programming, or discipline could be a Cat l weightlifter despite training for several years, but these guidelines will be true for most people.

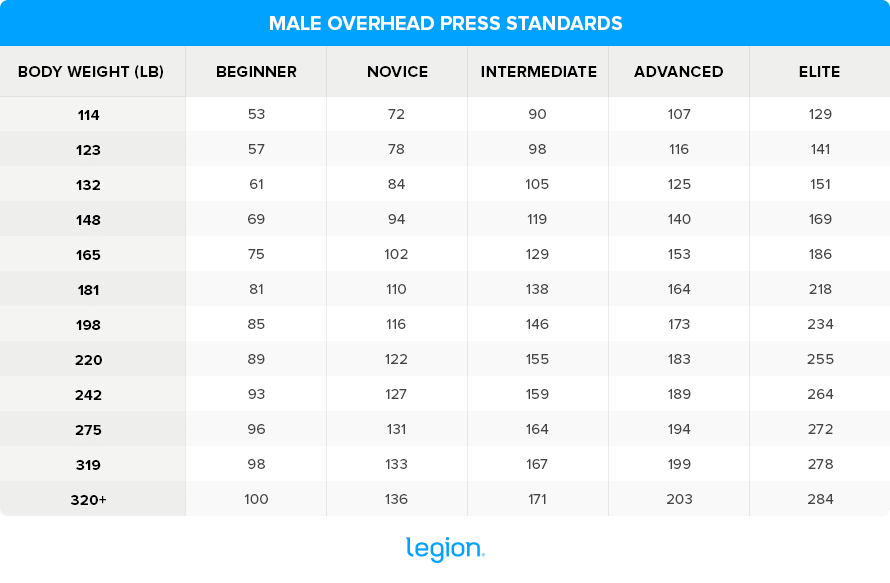

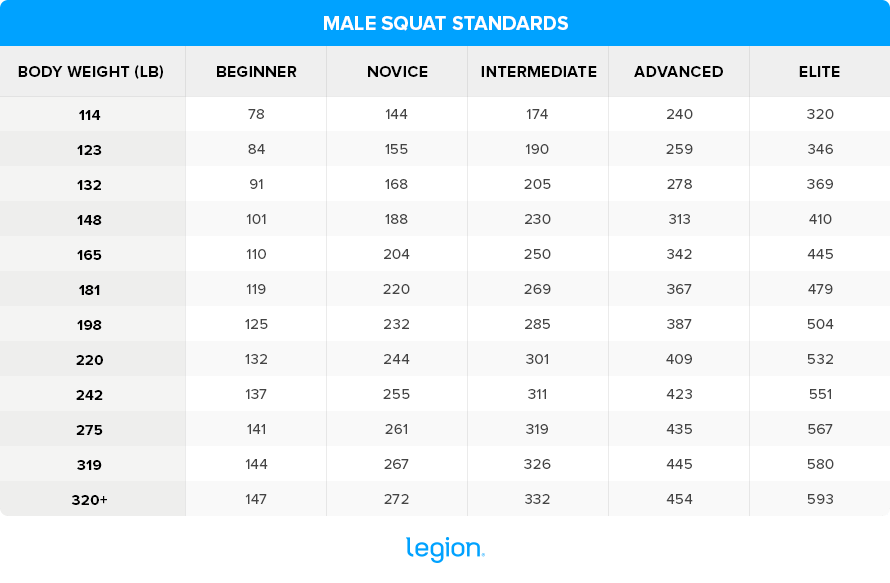

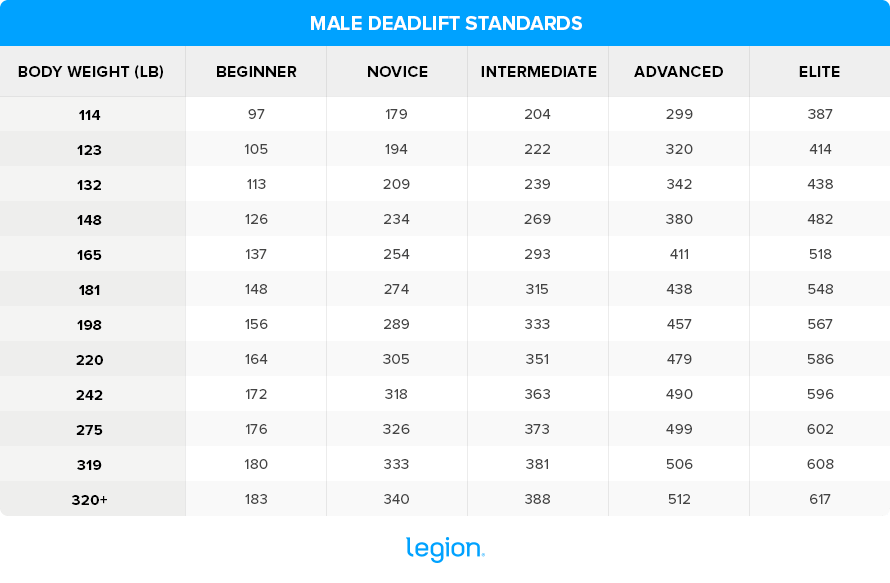

Rippetoe’s strength standards have the advantage of being in table form, which shows you exactly how much weight you should aim for based on your body weight and sex.

For instance, if you’re a 180-pound adult man who’s been lifting for 6 months, you can look at the table and know you should be able to bench press at least 128 pounds.

The downside of this system is that finding exactly how much you should be able to lift for each exercise and at each body weight is a little irksome. Additionally, it only provides standards for the squat, deadlift, and bench and overhead press, whereas Henriques’ system provides standards for those exercises and eight others.

Here are Mark Rippetoe’s strength standards for men:

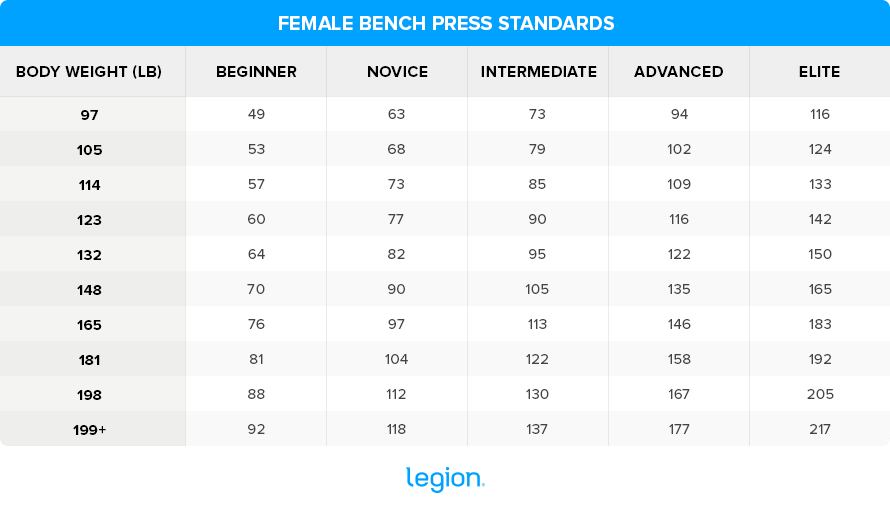

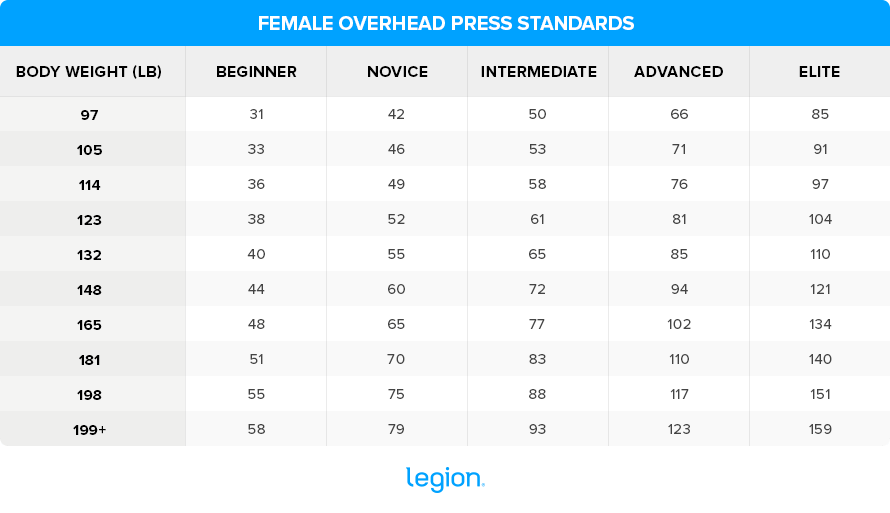

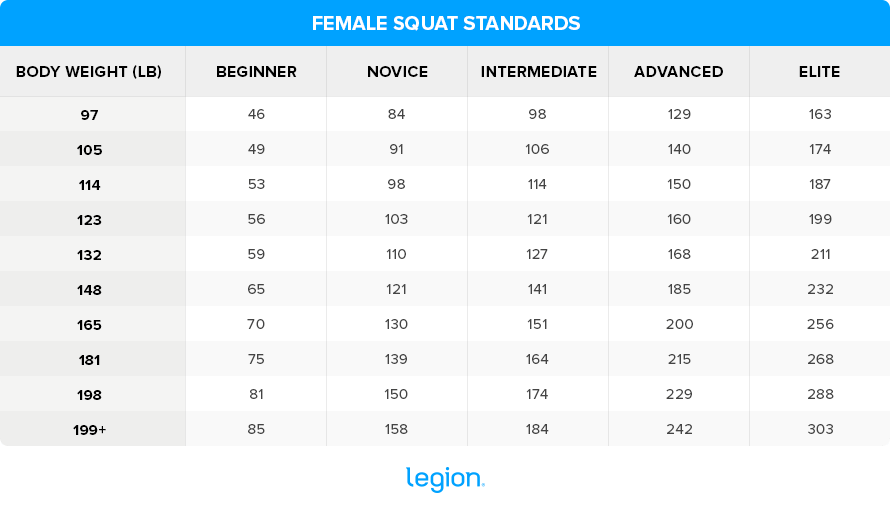

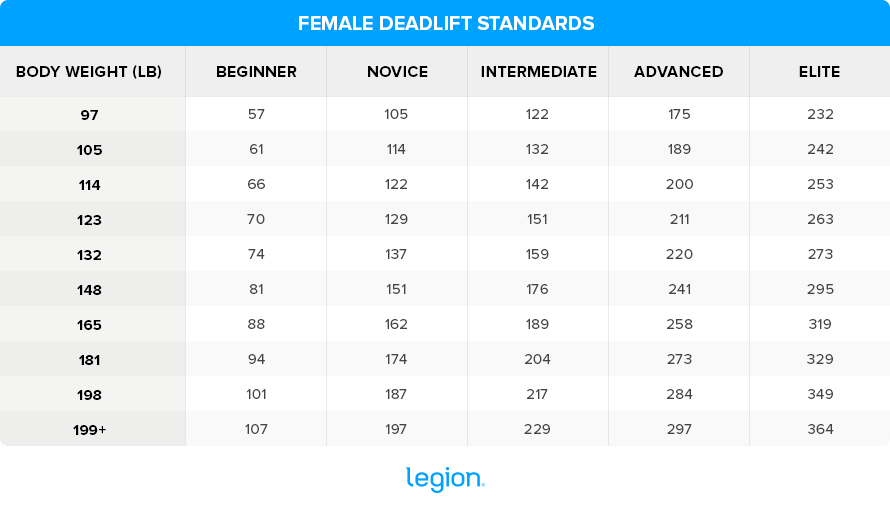

And here are Mark Rippetoe’s strength standards for women:

Why Strength Standards Can Be Misleading

All else being equal, the more muscle you have, the more you should be able to lift.

People with more muscle generally weigh more, too, which is why strength standards are higher or lower for heavier and lighter people, respectively.

The problem is that “all else” is rarely equal.

There are two main variables that can throw off your estimates:

- Your anatomy.

- Your age.

Let’s look at each.

How Your Anatomy Affects Your Strength

It can be easier or harder to get stronger on certain exercises because of where your tendons attach to your bones.

For example, if your biceps tendon attaches a few millimeters further away from your elbow, this improves the biceps’ leverage, which allows you to lift more weight.

If it attaches a few millimeters closer to your elbow, though, this decreases the biceps’ leverage, which reduces the amount of weight you can lift.

The effects can be huge, too.

Thanks to these small anatomical differences, one person could lift 25% more than another even if they had the same amount of muscle mass.

Another key anatomical feature that can affect your strength is your skeletal proportions.

We all have the same muscles and bones in our bodies, and they’re all located in the same general areas, but there can be differences in how long or short our bones are and where our tendons attach to them.

These differences tend to be as small as only a few millimeters, but that can translate into noticeable differences in strength.

Your bones function as levers, and how long or short those levers are can drastically affect how much you can lift.

For example, if someone has longer than average arms, they have to move the bar further to complete each rep of bench press. All else being equal, they won’t be able to bench press as much as someone with average length arms.

That same disadvantage can be helpful for other exercises, though. Long arms make deadlifting easier, because the bar doesn’t have to travel as far when you stand up.

That said, by definition most people have average length limbs and tendon attachment points, so strength standards can still give us a ballpark estimate of how we compare to others.

Just keep in mind that if you’re significantly weaker or stronger on some lifts, it could be that your anatomy is just better suited to some exercises than others.

How Your Age Affects Your Strength

As we age, we naturally lose strength

That doesn’t mean you can’t gain strength or muscle past a certain age, but it does get harder.

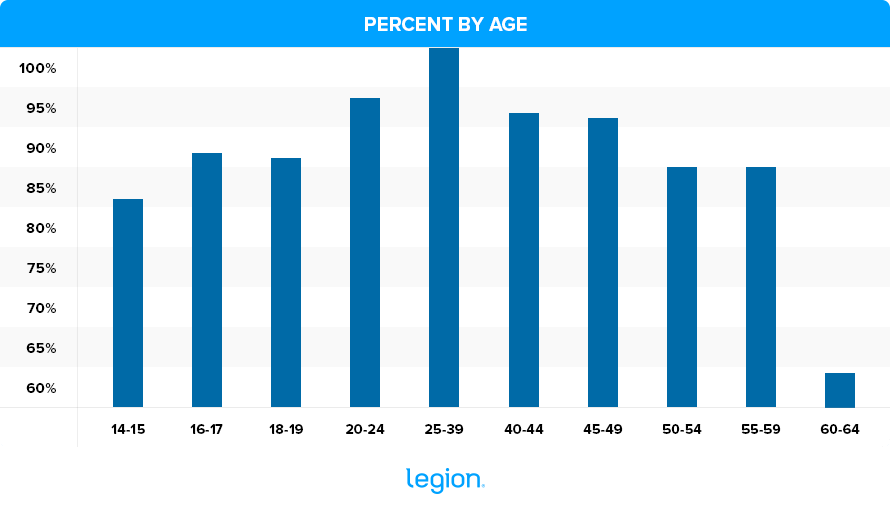

Take a look at this chart of record strength totals for lifters of different ages:

As you can see, most people can keep getting stronger up until about 40. After that, you’re doing well to maintain your strength, much less set new personal records.

This natural decline in strength is caused by a number of physiological changes, but you can minimize it by avoiding injuries, eating a healthy diet, and training intelligently.

(And if you want a fitness program that takes care of all of the above, and that’s specifically designed to help absolute beginners at any age and fitness level get in the best shape of their life, check out Mike’s newest fitness book for men and women, Muscle for Life.)

How to Set Strength Goals in 3 Simple Steps

If you want to compete in powerlifting, you should set goals based on the powerlifting strength standards of whatever federation you want to compete in.

Here are links to the two most popular sets of powerlifting strength standards:

Otherwise, I recommend that you use Mark Rippetoe’s strength standards because . . .

- They’re based on data from serious, natural weightlifters rather than the genetic elite or steroid users.

- They’re not based on self-reported data, which is often inaccurate because people tend to exaggerate.

- They’re based on data collected by a scrupulous third party, not an online survey that can easily be fudged.

Here’s what you need to do:

Step 1: Estimate Your One-Rep Maxes

If you don’t know your true one-rep maxes off hand or haven’t tested them in the past 12 weeks, use the calculator below to estimate your one-rep max for your squat, deadlift, and bench and overhead press based on how many reps you can get with a lighter weight.

Step 2: Compare Your One-Rep Maxes to Strength Standards

Pick which exercise you want to look at then find the corresponding chart from earlier in this article.

For instance, let’s say I wanted to compare my bench press against Mark Rippetoe’s bench press strength standards, here’s the chart I’d need:

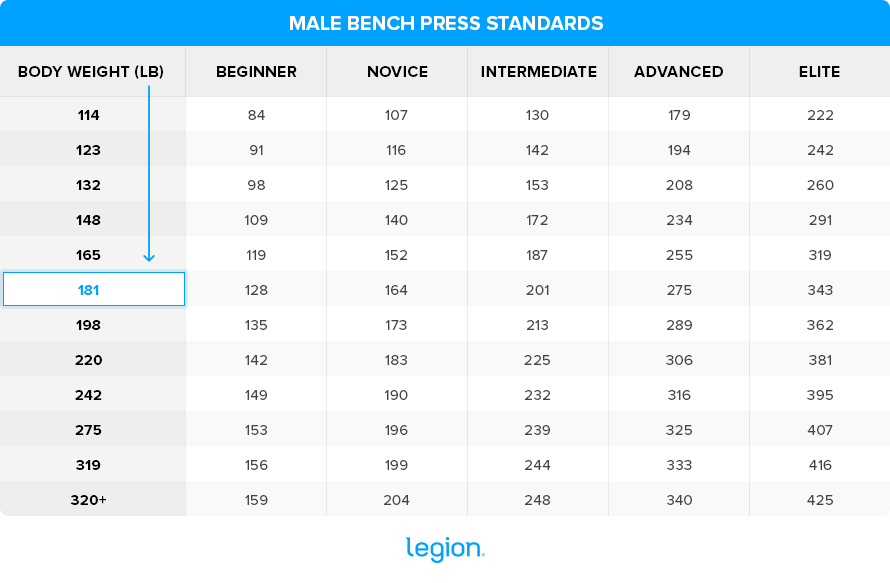

After locating the chart, I’d locate my body weight in the far left-hand column. If your weight isn’t listed, use the category that’s closest to your weight.

I weigh 175 pounds, so I would use the strength standards for someone who weighs 181 pounds.

Follow that row to the right until you find the number that is closest to your one-rep max:

If the number is bigger than your one-rep max, use the number to the immediate left of it. If the number is smaller than your one-rep max, then use that number.

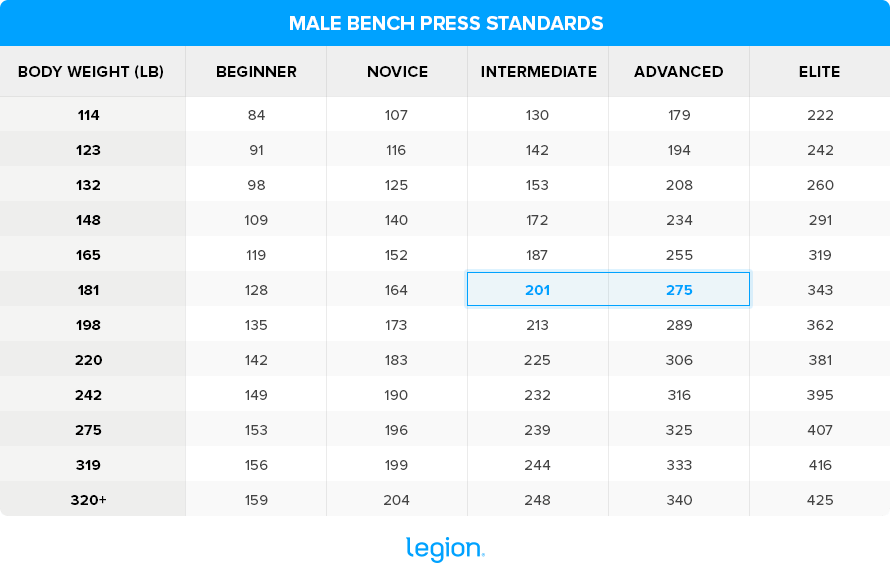

You always choose the lower number because each number indicates the minimum amount of weight you need to lift to reach that category. For example, if I bench pressed 260 pounds, I’d still be in the Intermediate category, because I didn’t quite get 275 pounds (which is the minimum for entering the Advanced category).

Once you’ve found the correct number, follow that column up, and you’ll find your strength category.

To continue the example, my 320-pound bench puts me in the Advanced category:

Repeat this process with all of your lifts.

Remember that you’ll probably have one or two lifts that lag behind the others (for me it’s the deadlift), and that’s fine. The whole point of these standards is to find what you need to work on the most and to set goals for your future progress.

Step 3: Set Reasonable, Challenging Strength Goals

There are a few ways to go about this, but the simplest is to focus on whatever you’re worst at.

In other words, if your bench press and deadlift are both in the Intermediate category, but your squat puts you in the Beginner category, stop skipping leg day and knuckle down on your squat.

You should also consider what parts of your physique you want to improve the most. Remember that strength and size are closely correlated, so the muscle groups most involved in whatever lift you focus on are also generally going to grow the most.

For instance, if your bench press is your best lift according to the strength standards, but you still want your chest to grow more than your legs, back, or shoulders, then it makes sense to focus on improving your bench versus your squat, deadlift, or overhead press.

Once you’ve decided what exercise to focus on, a good goal to aim for is to try to move up one category from where you are now. Bear in mind, though, that the closer you get to your genetic potential, the longer it’ll take to “level up.”

You can also boost your rankings by maintaining your strength while losing body fat and dropping into the next weight category.

For example, let’s say you weigh 148 pounds and can overhead press 95 pounds, putting you in the Novice category. If you were to lose 16 pounds and get your body weight to 132, you’d only have to add 10 pounds to your overhead press to bump yourself up to the Intermediate category.

How to Get Stronger

The best way to get stronger is to follow a strength training plan that allows you to progressively overload your muscles.

That is, you need to organize your training in such a way that you can consistently add weight and reps to compound exercises like the squat, deadlift, and bench and overhead press.

If you want to learn the best ways to do that, check out these articles:

- The 12 Best Science-Based Strength Training Programs for Gaining Muscle and Strength

- The Definitive Guide on How to Build a Workout Routine

- Get Strong Fast With the 5/3/1 Strength Training Program

Supplements aren’t essential for getting stronger, but the right ones can help you train harder, recover faster, and get better results from your workouts. Here are three worth considering:

- Protein powder: Protein powder, such as whey or casein, provides your body with the nutrients needed to build muscle tissue and recover from workouts. For a clean and delicious protein powder, try Whey+ or Casein+.

- Creatine: Creatine boosts muscle and strength gain, improves anaerobic endurance, and reduces muscle damage and soreness from your workouts. For a natural source of creatine, try our creatine monohydrate, creatine gummies, or Recharge.

- Pre-workout: A high-quality pre-workout enhances energy, mood, and focus, increases strength and endurance, and reduces fatigue. For a top-tier pre-workout containing clinically effective doses of 6 science-backed ingredients, try Pulse with caffeine or without.

(If you’d like even more specific advice about which supplements you should take to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what supplements are right for you.)

FAQ #1: Where can I find strength standards for every exercise?

You can’t, but here are some good ballpark figures for the most common exercises that people want to track.

Note: In all of the following examples, “Beginner” refers to anyone who’s been consistently training for 6-to-12 months, “Intermediate” refers to anyone who has been consistently training for 1-to-3 years, and “Advanced” refers to anyone who has been consistently training for more than 3 years. All strength standards refer to the minimum you should be able to lift for a single rep (one-rep max) unless stated otherwise.

Front Squat Strength Standards:

Beginner: 0.8 times your body weight

Intermediate: 1.2 times your body weight

Advanced: 1.5 times your body weight

Leg Press Strength Standards:

Beginner: 1.2 times your body weight

Intermediate: 2 times your body weight

Advanced: 3 times your body weight

Trap-Bar Deadlift Strength Standards:

Beginner: 0.8 times your body weight

Intermediate: 1.7 times your body weight

Advanced: 2.2 times your body weight

Sumo Deadlift Strength Standards:

Beginner: 0.8 times your body weight

Intermediate: 1.7 times your body weight

Advanced: 2.2 times your body weight

Incline Barbell Bench Press Strength Standards:

Beginner: 0.5 times your body weight

Intermediate: 0.8 times your body weight

Advanced: 1.1 times your body weight

Barbell Row Strength Standards:

Beginner: 0.6 times your body weight

Intermediate: 0.9 times your body weight

Advanced: 1.2 times your body weight

Pull-up Strength Standards:

Beginner: 3-to-5 reps with your body weight

Intermediate: 5-to-10 reps with your bodyweight or at least 1 rep with your bodyweight plus 20 percent.

Advanced: 10-to-15 reps with your bodyweight or at least 1 rep with your bodyweight plus 40 percent.

FAQ #2: Can you classify strength standards by age and weight?

You can find strength standards by age and weight online, but they’re not necessarily applicable to recreational weightlifters because they’re based on data from competitive weightlifters.

If you still want to see how you compare, though, check out Symmetric Strength Standards here.

FAQ #3: What is a strength standards calculator?

A strength standards calculator is an online calculator that tells you how advanced you are at a given exercise based on data such as your weight, the amount you can lift, and the number of reps you can do.

The problem with strength standards calculators is they are based on self-reported data, which tends to be inaccurate because it’s easily corrupted by people who exaggerate how much they can lift, intentionally input false data, or take steroids.

Scientific References +

- Keller, K., & Engelhardt, M. (2013). Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal, 3(4), 346. https://doi.org/10.11138/mltj/2013.3.4.346

- Delp, S. L., & Maloney, W. (1993). Effects of hip center location on the moment-generating capacity of the muscles. Journal of Biomechanics, 26(4–5), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(93)90011-3

- Trezise, J., Collier, N., & Blazevich, A. J. (2016). Anatomical and neuromuscular variables strongly predict maximum knee extension torque in healthy men. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2016 116:6, 116(6), 1159–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-016-3352-8