If you’ve ever wondered, “Why does my weight fluctuate so much?” you’re not alone.

Weight fluctuation can be baffling.

However, regardless of whether you’re trying to lose, gain, or maintain your weight, these fluctuations are perfectly normal.

In this article, you’ll learn why your weight fluctuates and how to weigh yourself to accurately track your weight.

Why Does My Weight Fluctuate So Much?

Your body weight is never static.

Whether you’re trying to lose, gain, or maintain weight, it’ll likely fluctuate across each day, week, and month, often inconsistently and unpredictably.

Many aren’t aware of this. While dieting, for example, they expect weight loss to be a smooth, linear process like this:

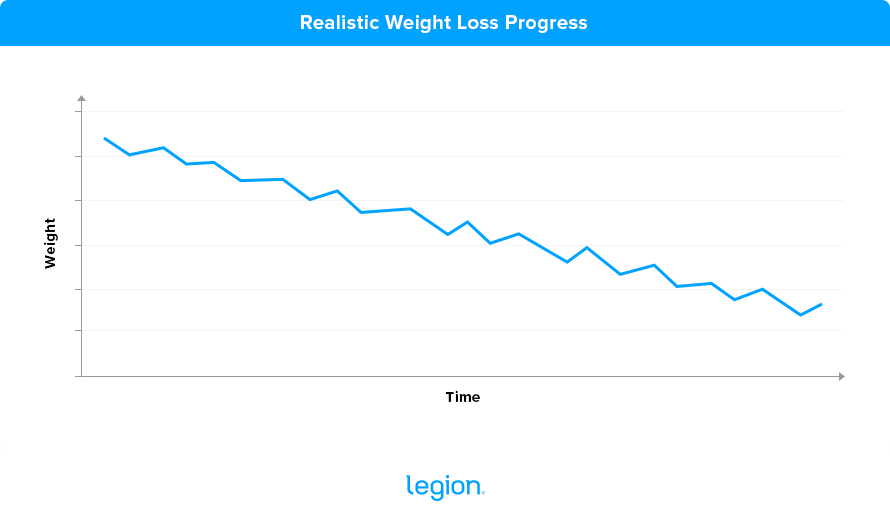

In reality, this isn’t how weight loss occurs—you may lose a pound one week, then nothing over the next two, suddenly lose three pounds the following week, gain a pound back, lose it a few days later, and so forth.

And this means your progress actually looks more like this:

While many attribute uneven progress to dietary inconsistency, it’s in fact perfectly normal. Everyone experiences it, and it’s influenced by our diet, lifestyle, and biology.

Let’s delve deeper into the main reasons behind why weight fluctuates.

Weight Fluctuation From Food Weight

Eating food causes an immediate increase in your weight because food’s mass doesn’t disappear when you swallow it—it must first pass through your digestive system.

The food in an average meal weighs a few ounces, so you’ll likely gain a few pounds in food weight daily.

Don’t let this worry you.

The weight gained from food is temporary and will decrease as your body digests the food and expels waste. This process can take 1-to-3 days, depending on the individual and the composition of the meal.

Weight Fluctuation From Carbohydrates

Your body converts the carbohydrates you eat into glycogen, which it stores in your muscles and liver.

It also holds 3-to-4 grams of water with every gram of stored glycogen, which is why eating a high-carb meal can make your weight swing upward.

For instance, two slices of bread contain enough carbs to make your body store an extra ~⅓ of a pound of water.

However, this weight diminishes once you use the glycogen for energy.

(If you’d like specific advice about which foods you should eat to reach your fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.)

Weight Fluctuation From Sodium

Sodium brings water into cells, which is why eating salty foods can make you gain several pounds (of water weight) within hours.

Although your body can adjust to varying sodium intakes, eating lots of high-sodium foods can lead to water retention for a couple of days.

Remember, this isn’t fat gain—the water weight will drop once the body processes the extra sodium.

Weight Fluctuation From Stress

Prolonged stress prompts the body to produce cortisol, a hormone that causes your weight to fluctuate for four main reasons:

- It increases water retention.

- It increases ghrelin, which goads you into eating more, increasing food weight in your body.

- It triggers cravings for “comfort foods.” These foods bump up your body weight because they’re easy to overeat (increasing food weight) and they’re usually high in sodium (exacerbating water retention).

- It may disrupt your sleep, which can cause lower leptin (the “satiety hormone”) levels and promote further overeating.

The best ways to reduce cortisol are:

- Get plenty of sleep.

- Drink less alcohol.

- Engage in relaxing activities such as reading, listening to calming music, or walking.

- Eat a nutritious diet.

- Do low-to-moderate-intensity exercise.

- Take supplements, such as fish oil and ashwagandha.

(If you’d like more specific advice about which supplements you should take to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.)

Weight Fluctuation From Stool Weight

Our body’s fecal weight also contributes to weight fluctuations.

Research shows that the daily stool weight can vary, but typically ranges from ~2.5 ounces to 1 pound.

It also bears remembering that the digestive tract isn’t empty after a bowel movement. There remains digestible material still in transit, contributing to your body weight.

The average stool transit time—the duration it takes for food to travel from the mouth to the end of the digestive tract—ranges between 10 and 73 hours.

Eating enough dietary fiber can accelerate this transit time and promote regular bowel movements, potentially leading to more stable day-to-day weight measurements.

Weight Fluctuation From Exercise

Immediately after a workout, you may notice a small decrease in weight, primarily due to fluid loss through sweating.

This fluctuation will be short-lived, provided you rehydrate after your workout.

If you start strength training, you may notice that your weight creeps up. This isn’t cause for concern—it’s likely evidence that you’re building muscle, not that you’re gaining fat.

And if you want a strength training program designed to help you build muscle, lose fat, and get healthy, check out my programs for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger is right for you or if another strength training program might be a better fit for your circumstances and goals, take Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Weight Fluctuation From the Menstrual Cycle

Weight fluctuation throughout the menstrual cycle is a common phenomenon linked to the hormonal changes that govern the cycle.

The key hormones involved—namely estrogen, progesterone, and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)—can notably affect fluid balance, appetite, and digestion, which in turn can cause weight to vary throughout the month.

For instance, during the initial phase of the menstrual cycle (the “follicular phase”), estrogen levels rise, which is associated with mild fluid retention, resulting in slight weight gain.

Estrogen also curbs hunger, boosts leptin production, and mimics leptin’s effects in the brain, which can help control cravings and potentially reduce the likelihood of weight gain through overeating.

As estrogen levels fall after ovulation, leptin and the hormone serotonin sink and progesterone rises, increasing hunger and cravings for carb-rich food and, thus, the risk of binge eating and water retention.

The menstrual cycle also influences gastrointestinal transit time.

Studies suggest that this transit time varies throughout the cycle, often slowing during the late luteal phase, which can result in constipation and bloating, leading to an increase in body weight.

Weight Fluctuation From Alcohol

Drinking alcohol can cause your weight to fluctuate in a couple of ways:

- It’s a diuretic (it increases urine production), which means it can cause temporary weight loss.

- Drunkenness often prompts people to aggressively overeat (especially fat-, carb-, and sodium-rich foods), leading to increased food weight and water retention.

How to Weigh Yourself Correctly

Daily weight fluctuations are a given, so beating yourself up over minor increases or decreases in weight is silly.

Instead, calculate weekly averages to get an accurate picture of how your weight is trending.

Record your weight first thing every morning, while nude, after using the bathroom, and before eating or drinking.

After a week, add up your daily weights and divide the sum by seven. This gives you your average weight for that week.

Monitor these averages over time to see if you’re making the desired progress.

FAQ #1: How much can weight fluctuate in a day?

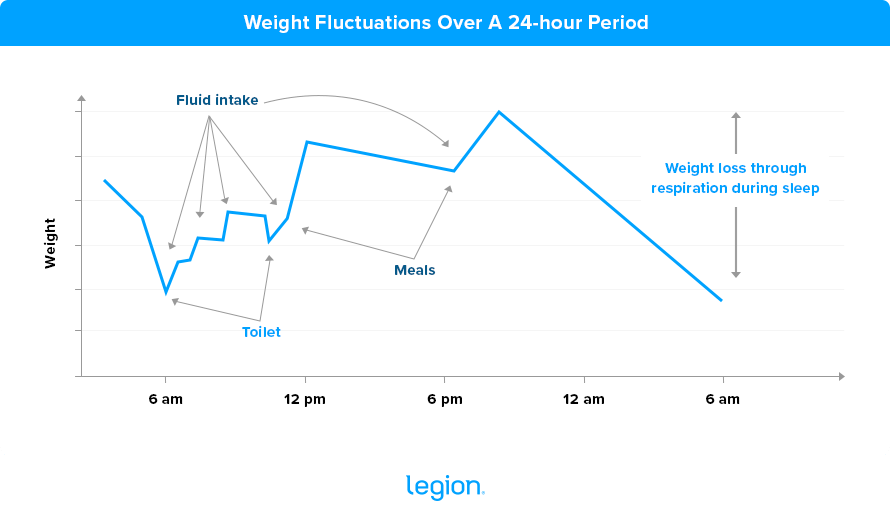

For adults, the average daily weight fluctuation is ~2-to-5 pounds, although this can differ from person to person.

Factors contributing to these variations include fluid balance, food and drink consumption, exercise habits, and bowel movements.

Weight tends to be lowest in the morning upon waking, and highest in the evening, after consuming meals and drinks throughout the day. Here’s a graph…

FAQ #2: Why does weight fluctuate?

Various factors contribute to weight fluctuation, including food and drink consumption, bowel movements, exercise, and hormonal changes.

For instance, consuming high-carb and salty foods may lead to fluid retention, resulting in a temporary weight gain.

Furthermore, hormonal fluctuations throughout a woman’s menstrual cycle can lead to increased food intake, water retention, and reduced bowel movements, causing weight gain.

Stress and alcohol consumption can also indirectly influence weight by affecting dietary behaviors.

FAQ #3: How much does weight fluctuate during your period?

Many women experience weight fluctuations during their period because of changes in eating habits, bloating, stress, and water retention.

However, pinpointing an “average” weight gain or loss during the menstrual cycle is unfeasible given the individual differences between women.

Scientific References +

- Lee YY, Erdogan A, Rao SSC. How to assess regional and whole gut transit time with wireless motility capsule. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2014;20(2):265-270. doi:https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm.2014.20.2.265

- Kreitzman SN, Coxon AY, Szaz KF. Glycogen storage: illusions of easy weight loss, excessive weight regain, and distortions in estimates of body composition. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;56(1):292S293S. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/56.1.292s

- Heer M, Frings-Meuthen P, Titze J, et al. Increasing sodium intake from a previous low or high intake affects water, electrolyte and acid–base balance differently. British Journal of Nutrition. 2009;101(09):1286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114508088041

- Whitworth JA, Mangos GJ, Kelly JJ. Cushing, Cortisol, and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension. 2000;36(5):912-916. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.912

- Adams CE, Greenway FL, Brantley PJ. Lifestyle factors and ghrelin: critical review and implications for weight loss maintenance. Obesity Reviews. 2010;12(5):e211-e218. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789x.2010.00776.x

- Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior. 2007;91(4):449-458. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, et al. Chronic stress and obesity: A new view of “comfort food.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(20):11696-11701. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934666100

- Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Cauter EV. Brief Communication: Sleep Curtailment in Healthy Young Men Is Associated with Decreased Leptin Levels, Elevated Ghrelin Levels, and Increased Hunger and Appetite. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141(11):846. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008

- Badrick E, Bobak M, Britton A, Kirschbaum C, Marmot M, Kumari M. The Relationship between Alcohol Consumption and Cortisol Secretion in an Aging Cohort. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;93(3):750-757. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-0737

- Iranmanesh A, Lawson D, Dunn B, Veldhuis JD. Glucose Ingestion Selectively Amplifies ACTH and Cortisol Secretory-Burst Mass and Enhances Their Joint Synchrony in Healthy Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(9):2882-2888. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0682

- Adan RAH, van der Beek EM, Buitelaar JK, et al. Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;29(12):1321-1332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.10.011

- Hill EE, Zack E, Battaglini C, Viru M, Viru A, Hackney AC. Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2008;31(7):587-591. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03345606

- Barbadoro P, Annino I, Ponzio E, et al. Fish oil supplementation reduces cortisol basal levels and perceived stress: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in abstinent alcoholics. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2013;57(6):1110-1114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200676

- Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Malvi H, Kodgule R. An investigation into the stress-relieving and pharmacological actions of an ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Medicine. 2019;98(37):e17186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017186

- Jahangard L, Hedayati M, Abbasalipourkabir R, et al. Omega-3-polyunsatured fatty acids (O3PUFAs), compared to placebo, reduced symptoms of occupational burnout and lowered morning cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;109:104384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104384

- Cummings JH, Bingham SA, Heaton KW, Eastwood MA. Fecal weight, colon cancer risk, and dietary intake of nonstarch polysaccharides (dietary fiber). Gastroenterology. 1992;103(6):1783-1789. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(92)91435-7

- Gear Js, A. J. M. Brodribb, Ware A, Mann J. Fibre and bowel transit times. 1981;45(1):77-82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn19810078

- Stachenfeld NS. Sex Hormone Effects on Body Fluid Regulation. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2008;36(3):152-159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/jes.0b013e31817be928

- Butera PC. Estradiol and the control of food intake. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;99(2):175-180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.06.010

- Gao Q, Horvath TL. Cross-talk between estrogen and leptin signaling in the hypothalamus. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;294(5):E817-E826. doi:https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00733.2007

- Davidsen L, Vistisen B, Astrup A. Impact of the menstrual cycle on determinants of energy balance: a putative role in weight loss attempts. International Journal of Obesity (2005). 2007;31(12):1777-1785. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803699

- Barth C, Villringer A, Sacher J. Sex Hormones Affect Neurotransmitters and Shape the Adult Female Brain during Hormonal Transition Periods. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2015;9(37). doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00037

- Fernández-Ruiz JJ, de Miguel R, Hernández ML, Ramos JA. Time-course of the effects of ovarian steroids on the activity of limbic and striatal dopaminergic neurons in female rat brain. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1990;36(3):603-606. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-3057(90)90262-g

- Arnoni-Bauer Y, Bick A, Raz N, et al. Is It Me or My Hormones? Neuroendocrine Activation Profiles to Visual Food Stimuli Across the Menstrual Cycle. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017;102(9):3406-3414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-3921

- Hirschberg AL. Sex hormones, appetite and eating behaviour in women. Maturitas. 2012;71(3):248-256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.016

- Wurtman RJ, Wurtman JJ. Brain Serotonin, Carbohydrate-Craving, Obesity and Depression. Obesity Research. 1995;3(S4):477S480S. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00215.x

- Dye L, Blundell JE. Menstrual cycle and appetite control: implications for weight regulation. Human Reproduction. 1997;12(6):1142-1151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/12.6.1142

- Heitkemper MM, Chang L. Do fluctuations in ovarian hormones affect gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome? Gender Medicine. 2009;6(2):152-167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genm.2009.03.004

- Polhuis K, Wijnen A, Sierksma A, Calame W, Tieland M. The Diuretic Action of Weak and Strong Alcoholic Beverages in Elderly Men: A Randomized Diet-Controlled Crossover Trial. Nutrients. 2017;9(7):660. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070660

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Lucero ML, DiBello JR, Jacobson AE, Wing RR. The relationship between alcohol use, eating habits and weight change in college freshmen. Eating Behaviors. 2008;9(4):504-508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.06.005

- Bhutani S, Kahn E, Tasali E, Schoeller DA. Composition of two-week change in body weight under unrestricted free-living conditions. Physiological Reports. 2017;5(13):e13336. doi:https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13336