Barefoot shoes are minimalist shoes with thin soles that aim to approximate the sensation of walking or running completely barefoot.

Proponents of minimalist footwear often claim that modern shoes with their narrow, constrictive shape and thick soles wreak havoc on people’s anatomy and joints—scrunching the toes and throwing the ankles, knees, and hips out of alignment, which damages joints and undermines your running efficiency.

Instead, they argue, the only function of shoes should be to protect the bottom of your feet, nothing more.

Others think this is horsefeathers.

According to these folks, modern footwear is a significant stride (harhar) ahead of barefoot shoes, and the latter is just a contrarian fad.

Who’s right?

Table of Contents

+

What Are Barefoot, Minimalist, and Zero-Drop Running Shoes?

The term “barefoot shoes” is something of an oxymoron.

If you’re shod, then you aren’t barefoot by definition, but this term refers to shoes that are as thin and light as possible to mimic the sensation of being barefoot.

“Minimalist shoes” can refer to many different kinds of shoe styles that may or may not be “barefoot,” but are generally lighter, thinner, and more flexible than most running shoes.

“Zero-drop” running shoes are shoes where the sole is the same thickness throughout, instead of being thicker under the heel and thinner under the toes like most shoes.

Technically, a shoe can be zero drop without being barefoot (for example, a thick, heavy boot with a sole that’s an inch thick from heel to toe), and a shoe can be barefoot without being zero drop (a superlight sandal with a sole that’s 4 mm thick under the heel and 2 mm under the toes). Withal, most barefoot shoes are zero drop and most modern shoes are not, so the terms are somewhat interchangeable.

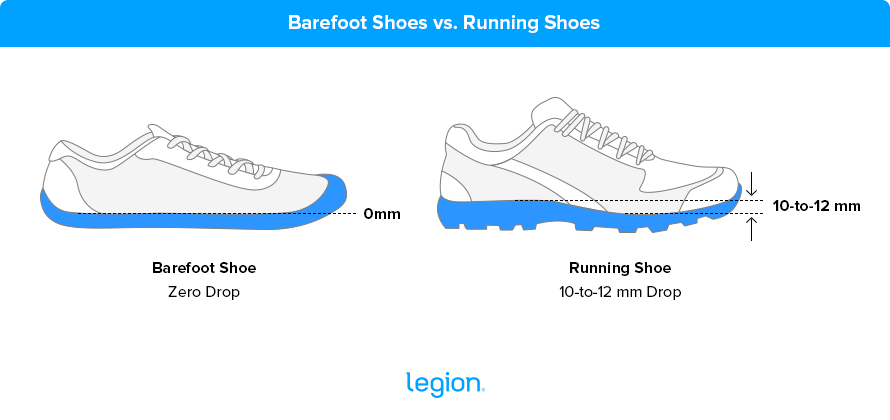

To better understand what makes a shoe “barefoot,” “minimalist,” or “zero drop,” it’s helpful to contrast them with modern running shoes, which have several features:

- A thick, cushioned sole designed to absorb some of the impact of your feet hitting the ground as you run, thus making running more comfortable and easier on your joints. Most running shoe soles are about 1-to-2 inches thick. Due to their thick soles, most modern running shoes also tend to be heavy (usually weighing about 10-to-12 ounces per shoe).

- The sole tends to be much thicker under the heel and gets progressively thinner toward the forefoot, which creates a “heel-to-toe-drop” of 10-to-12 millimeters (about half an inch). The idea is that since you should land on your heels when you run, this extra cushion absorbs more of the impact.

- Relatively narrow soles and uppers (the cloth part of the shoe that holds the sole in place), which is mostly an aesthetic choice.

Here’s what these differences look like:

Why the design differences?

Almost all modern running shoes are designed under the assumption that most of us have subtle anatomical quirks and movement patterns that can work against us if they aren’t ameliorated by proper (modern) running shoes.

For example, Asics claims on their website that “Research shows that around 4 in 5 runners risk injury in shoes that don’t suit their running style. Understanding how your feet move and land will help you find shoes with the right type of support for you.” Brooks boasts that their “GuideRails® technology adds support by keeping excess movement in check.” Nike says of one of its shoes, “A wider forefoot provides stability to prevent rolling, while the high foam heights provide soft responsiveness and long-lasting comfort.”

The biggest bogeymen these companies gin up is an excessive inward rolling of the foot while running, which they refer to as over-pronation, and which is supposedly fixed with “motion control” technology built into the soles. Another favorite hobbyhorse of shoe companies is the idea that many people have “fallen arches” or “flat feet,” which must be bolstered with “arch support” built into the soles (this just means the shoe has additional material under the arch of the foot). There’s also an entire cottage industry of companies that make “shoe orthotics”—custom made (and costly) insoles that supposedly reduce and prevent pain while running and walking.

Advocates of barefoot shoes start with the opposite assumption:

Humans evolved wearing no or very minimal (probably leather or thin cloth) footwear, so strapping a thick, strangely shaped piece of foam to the bottom of our feet disrupts our inborn running gait and can lead to discomfort, injuries, and inefficient technique. Instead, shoes should only be as thick as necessary to protect our feet against dirt, debris, and the elements, and no more.

To that end, barefoot shoes tend to have the following features:

- A thin, highly flexible sole, usually only ~3-to-6 mm (0.1-to-0.2 in) thick made of dense rubber similar to a bicycle tire.

- The sole is generally the same thickness throughout, with “zero drop” from heel to toe. The idea is that this allows your foot to move in the most natural way possible while running.

- Relatively wide soles and uppers that allow your feet and toes to spread as far forward and sideways as you like. Generally, the heel and midsection of the shoe will feel snug and secure so that your feet don’t slide around, but the toe box area will be roomy to ensure your toes aren’t pinched or constricted while running.

Generally, barefoot shoes are also much lighter than traditional running shoes, often weighing only 6-to-8 ounces per shoe.

Minimalist trail running shoes are simply barefoot shoes with slightly more aggressive tread to improve traction on soft, slick, or unstable surfaces.

The paragon of minimalist footwear are barefoot sandals, which are essentially just a thin, lightweight flap of rubber strapped to the bottom of your foot with lightweight string. For example, these barefoot sandals from Xero are only 4 mm thick and weigh 3.5 ounces each (in other words, a pair of these sandals weigh significantly less than just a single modern running shoe).

A Brief History of Barefoot Running Shoes

Archeological evidence of human activity over the past 10,000 years shows that people walked and ran either barefoot or with thin sandals or shoes that were meant to protect the soles of their feet, not cushion their footfall or alter their biomechanics.

One of the oldest examples of footwear are a pair of thin sandals woven from sagebrush bark, which were discovered in a cave in Oregon and are thought to be about 9,000 years old:

When Howard Carter excavated King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, he found a pair of the archon’s ~3,000 year old sandals, which are essentially minimalist gilded flip flops:

Archeological evidence shows that the ancient Greeks and Romans often went barefoot as well. Although they sometimes wore thick boots such as the cothurnus or caligae, they generally wore relatively thin leather sandals or lightweight ankle boots such as the soleae, soccus, calceus, pero, krepis, pedila, and others. Earlier this year, archaeologists found a 1,500-year-old sandal in Norway that is almost identical to the ones worn by the Romans (basically just a strip of leather strapped to the sole of the foot).

Here’s an depiction of a typical Greek sandal:

(Note the thin sole that follows the shape of the foot.)

In other words, minimalist shoes and sandals have been worn around the world, by almost all cultures, made of a variety of materials, throughout almost all of human history. They generally only wore thick-soled, heavier shoes or boots for specific purposes, such as in cold, wet conditions, on slippery surfaces, or to enhance their stature.

Over time, fashions and fancies changed and people began to wear heels, high-heeled boots, and other forms of thicker footwear. This was primarily due to the desire to appear taller or out of practical necessity (heels helped horsemen keep their feet in their stirrups, for example). Few people wore these thick, high-heeled shoes when running, though.

Although running is one of the earliest known sports, it enjoyed a surge in popularity in the late 1800s, after which running footwear evolved to include features such as spikes, canvas uppers, and rubber soles. Some of the first modern running shoes were invented by Adolph Dassler, who later founded Adidas (“ADI” + “DASsler”).

Dassler’s shoes resembled thin, flexible leather slippers that conformed to the shape of the foot and were often worn without socks, with spikes attached for track and field events:

Most athletes wore some version of these thin shoes, such as Paavo “The Flying Finn” Nurmi during this 25-mile Olympic trial in 1932:

While the materials and construction of these shoes was new, their overall design was still remarkably similar to what ancient Greeks and Romans wore.

Even after these technological advances, some of the world’s best runners preferred to run barefoot. For example, Abebe Bikila ran barefoot when he won gold in the 1960 Olympic marathon, and Michael “Bruce” Tulloh ran barefoot when he won the 5,000 meter race at the 1962 European championships.

Things began to change in the 1970s, when jogging began to gain currency in the US and elsewhere. Canny marketers caught on to this uprush of popularity, and spotted a potentially lucrative perforation in the market.

As you’d expect when a large number of people jump into a new activity, there was a large rise in running-related injuries. And as is always the case when there’s a large number of people desperate to solve a problem, footwear companies were happy to offer a solution: shoes that (supposedly) minimized your risk of harming your hips, knees, ankles, and feet by cushioning your steps and altering your stride.

Thus arose the modern running shoe, with its thick, heavy soles designed to remedy your biomechanical imperfections.

In the past few decades, though, more and more evidence has shown that these “advances” may be more regressive than progressive.

In 2004, scientists at the University of Utah released a study of fossil evidence that they believed showed “endurance running is a derived capability of the genus Homo, originating about 2 million years ago, and may have been instrumental in the evolution of the human body form.” Other studies soon emerged supporting the idea that running long distances gave humans a significant evolutionary advantage over other predators and prey animals.

In other words, humans have been running since we could stand upright, and this activity has probably had a significant impact on our anatomy. As you saw a moment ago, we were running barefoot or in very minimalist shoes during this time.

This made many people wonder: is meddling with our biomechanics by wearing modern shoes actually interfering with our naturally-evolved movement patterns?

Are modern, thick-soled shoes the sartorial equivalent of margarine instead of butter?

That’s essentially the conclusion of a recent review paper published by a team of scientists led by Dr. Irene Davis, a researcher at Harvard Medical School. They argue that modern shoes disrupt our natural stride in a way that worsens our balance, coordination, and running efficiency, weakens the muscles and connective tissues in our feet, and increases our risk of injury, and that wearing minimalist shoes helps solve these problems. As the researchers conclude, “. . . modern footwear represents an evolutionary mismatch that may increase the risk for injury.”

While there’s still some debate as to whether modern running shoes cause injuries, there’s plenty of evidence to show they aren’t necessary or beneficial for most people.

Should You Run in Barefoot Shoes?

Potential Benefits

One of the main reasons people first become interested in barefoot running is the idea that this will reduce their risk of injury, and there’s some research to back this up.

This idea largely pivots on the idea that wearing barefoot running shoes encourages what’s known as a fore-foot strike. This means that when placing your foot on the ground while running, the ball of your foot makes contact before the heel (which is known as heel striking).

For example, one study published in Sports Biomechanics found that runners were 9.2 times more likely to run with a fore-foot strike in barefoot compared to regular running shoes, which is often said to be more efficient and easier on the joints. That said, the same study also found that 70% of the runners quickly reverted to a rear-foot strike, even when they wore barefoot shoes (old habits are hard to break!).

That said, calculating how footwear changes running biomechanics is a multiplex affair, and other research using different mathematical models has found that running barefoot doesn’t reduce impact forces versus running shod. Research investigating whether barefoot running increases efficiency often uncovers conflicting results, with some reviews suggesting barefoot shoes offer no benefit over traditional shoes.

It’s also not entirely clear if forefoot striking is superior to heel striking or midfoot striking (landing on the ball and heel of your foot at roughly the same time). For instance, an informal analysis of the foot strike patterns of Olympic 10 kilometer trial runners found that some of them had a forefoot strike, others a heel strike, and others a midfoot strike. While you could say that the mid- and rear-foot strikers would have done better if they adopted a fore-foot strike, there’s not much evidence to show that’s the case. Instead, it seems more likely that your foot strike pattern largely depends on your anatomy.

Several other studies have found no difference between running shod and barefoot when it comes to leg impact forces, and instead indicate that the speed at which your feet hit the ground is the primary determinant of how much punishment your joints absorb.

At least one study found that barefoot running shoes reduce the demands placed on your knees but increase the loads placed on other parts of your body (your ankles, for example), making the overall effect a wash.

There are other benefits of wearing barefoot shoes, though. The review study referenced earlier from Dr. Irene Davis shows that there’s also a strong argument to be made that minimalist shoes improve your running efficiency. Or, rather, barefoot shoes may not interfere with your body’s already efficient stride like modern running shoes do.

Barefoot running shoes may also improve proprioception (your awareness of the position of your body), which could improve your balance, coordination, and running efficiency. For instance, a study conducted by scientists at the University of Sydney found that children who wore minimalist shoes improved their balance and long jump performance more than kids who wore traditional shoes.

Studies also show that barefoot shoes may help reduce knee pain, particularly in people with osteoarthritis, and strengthen your foot and ankle muscles.

Walking barefoot can also help people with flat feet strengthen their foot arches and prevent pronation (the inner part of your ankle dropping toward the floor), and it’s reasonable to assume wearing barefoot shoes would offer similar benefits.

Finally, an often underappreciated benefit of barefoot running shoes (and one of the main reasons I’ve become a convert), is they’re usually lighter than traditional shoes, which makes them more efficient and comfortable for most. Every pound added to your feet costs about five times more energy than a pound worn on your back so wearing lighter shoes typically improves your running and walking efficiency once you adjust to the change.

Thus, while barefoot running shoes are no panacea, they may offer some significant benefits. What’s more, the evidence certainly doesn’t support the superiority of modern running shoes, and refutes much of the marketing puffery promoted by shoe companies.

Potential Drawbacks

The most common criticism of barefoot running shoes is that they increase your risk of injury.

While there’s a grain of truth to this, the root cause is usually user error rather than the shoes themselves.

In nearly every case I’ve come across of someone hurting themselves while wearing barefoot shoes, the person switched from running exclusively in traditional shoes to barefoot shoes. This can lead to achilles tendinitis or tendinosis, plantar fasciitis, and sometimes even knee pain as the connective tissues in your joints struggle to adapt to the rapid change. You also see this in the scientific literature, where folks accustomed to traditional shoes can develop injuries when they’re made to run in barefoot shoes without a sufficient break-in period.

Instead, a good rule of thumb is to do no more than 50% of your weekly running in barefoot shoes for your first few weeks. Or, if you’re hellbent on only running in barefoot shoes, reduce your running volume by at least 50% and gradually increase it over the next few weeks or months, depending on how you feel.

Another common stone thrown at barefoot running shoes is that they don’t adequately protect your feet. It’s true that barefoot running shoes are thinner and more flexible than traditional shoes, but there are a few reasons this doesn’t matter much in practice:

- Most of us run on paved or well-groomed roads and trails, where there are few sharp objects like broken bottles, roots, rocks, trash, etc.

- As you become accustomed to barefoot running, you’ll naturally become more aware of where you place your feet. You could even argue this is safer than mindlessly clomping over whatever happens to be in front of you, as many folks do when wearing thick shoes.

All in all, there aren’t many downsides to giving barefoot running shoes a shot so long as you make the transition gradually.

The Bottom Line on Barefoot Running Shoes

On the whole, it’s hard to crown barefoot running shoes as the clear champion over traditional running shoes.

Biomechanics is a murky field of study, and it’s difficult to conduct randomized controlled trials of how different shoes bear up on injury rates, efficiency, impact forces, comfort, and other variables. One of the reasons for this is that our perceptions of the gear we use when training can significantly influence our performance, and it’s nearly impossible to eliminate this factor when conducting studies on shoes (how do you ensure someone doesn’t realize they’re wearing barefoot shoes, for instance?).

When you look at the body of evidence and connect the dots, there’s reason to think barefoot running shoes may offer some benefits over traditional shoes, especially if you find them more comfortable (as I do). That said, it’s also possible that some people, whether due to firmly ingrained habits or anatomical quirks, don’t fare so well wearing barefoot shoes, but there’s no harm in trying them.

Another key takeaway from all of this is that there’s remarkably little evidence for the superiority of modern, thick-soled, high-heeled running shoes over minimalist ones. Ignore the hokum regarding arch support, pronation control, energy return, special foams, and the rest of it, and just go with what you find most comfortable.

For my part, I’ve always liked and followed the advice of “running in the least amount of shoe you can comfortably get away with.” At this point, I only run, hike, or ruck in barefoot running shoes or sandals, with the exception of very wet, cold, or uneven terrain, where I prefer thicker (although still fairly minimalist) footwear.

The 3 Best Barefoot Running Shoes

There are many great barefoot running shoes, but the following are three of my favorites.

Xero Speed Force

Xero is one of the best brands when it comes to minimalist footwear, and the Speed Force is their lightest and most minimalist shoe. The outsole is just 4.5 mm thick (and you can remove the already-thin insole to make them even more minimalist, and the upper is a fine mesh reinforced with Xero’s unique lacing pattern that keeps the shoes in the right place.

I wear these just about every day, although I’m also a fan of their Mesa Trail shoe for hiking and trail running, and their 360 for weightlifting.

Weight: ~330 grams/11.6 oz per pair

Sole Thickness: 4.5 mm (7.5 mm with insole)

Zero Drop: Yes

Merrell Vapor Glove

The Merrell Vapor Glove has one of the thinnest soles of any barefoot running shoe at only 2.5 mm thick, which is why they’re also about as light as the Speed Force. I’ve generally found the Speed Force to be more comfortable and secure, but the Vapor Glove is also a viable option.

Weight: ~330 grams/11.6 oz per pair

Sole Thickness: 2.5 mm (6.5 mm with insole)

Zero Drop: Yes

Wildling Nebula

Wildling is a lesser-known brand of barefoot shoes from Germany, and the Nebula is one of their lightest models. The upper is made of a combination of knitted merino wool, lightweight polyester, and a high-strength thread called Dyneema, and the outsole is made of rubber and cork. I don’t personally have experience with these, but I’ve had several people recommend them to me.

Weight: ~300 grams/10.6 oz per pair

Sole Thickness: ~3 mm

Zero Drop: Yes

If none of these models tickle your fancy, I also recommend you check out the Feelmax Ounas, Groundies Active Men, and Vivobarefoot Primus Lite III.

FAQ #1: What are the best barefoot running shoes?

My personal favorite men’s barefoot running shoes (and the ones I wear most) are the Xero Speed Force.

They’re so light you barely realize you’re wearing them, and they’re stylish, durable, and come in several different colors. You can leave the insole in for slightly more cushion, or take it out for maximum sensation. They also make a woman’s version, which is a little narrower and comes in different colors. Their 360 model is also a good option, especially for weightlifting or sports that tend to be harder on shoes, like basketball.

When it comes to casual shoes, I’m partial to the Vivobarefoot Geocourt, which is essentially a barefoot version of classic 70’s tennis shoes.

If you’re interested in more casual or even formal barefoot/minimalist shoes, there are many brands to choose from. Some of my favorites are Angles Fashion, Groundies, Feelmax, and Wildling.

FAQ #2: What activities are barefoot shoes good for?

Anything and everything.

While barefoot shoes have become popular with runners and hikers, they’ve also caught on with weightlifters and regular folks legging it around cities, running errands, and so forth.

Wearing barefoot shoes may improve proprioception (your awareness of the position of your body) and balance, and thus it’s possible barefoot shoes could be beneficial for a number of sports.

Not long ago, your only options for barefoot shoes were dotty-looking athletic shoes. Now, though, you can find a number of stylish, casual barefoot shoes that look as good or better than traditional ones, so you can wear them for nearly all occasions.

I generally wear barefoot shoes all the time, unless I’m hiking in extremely wet, cold weather or doing something that requires specialized footwear (skiing, skating, or cycling, for instance).

FAQ #3: What are the best brands of barefoot and minimalist running shoes?

My favorite brands of barefoot and minimalist running shoes are: Xero, Vivobarefoot, Feelmax, Groundies, and Wildling.

Scientific References +

- Bramble, D. M., & Lieberman, D. E. (2004). Endurance running and the evolution of Homo. Nature, 432(7015), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE03052

- Lieberman, D. E., & Bramble, D. M. (2007). The evolution of marathon running : capabilities in humans. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 37(4–5), 288–290. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737040-00004

- Davis, I. S., Hollander, K., Lieberman, D. E., Ridge, S. T., Sacco, I. C. N., & Wearing, S. C. (2021). Stepping Back to Minimal Footwear: Applications Across the Lifespan. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 49(4), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000263

- Divert, C., Baur, H., Mornieux, G., Mayer, F., & Belli, A. (2005). Stiffness adaptations in shod running. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 21(4), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1123/JAB.21.4.311

- De Wit, B., De Clercq, D., & Aerts, P. (2000). Biomechanical analysis of the stance phase during barefoot and shod running. Journal of Biomechanics, 33(3), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00192-X

- Divert, C., Mornieux, G., Baur, H., Mayer, F., & Belli, A. (2005). Mechanical comparison of barefoot and shod running. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(7), 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2004-821327

- Lieberman, D. E., Venkadesan, M., Werbel, W. A., Daoud, A. I., Dandrea, S., Davis, I. S., Mangeni, R. O., & Pitsiladis, Y. (2010). Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature 2010 463:7280, 463(7280), 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08723

- Cheung, R. T. H., Wong, R. Y. L., Chung, T. K. W., Choi, R. T., Leung, W. W. Y., & Shek, D. H. Y. (2017). Relationship between foot strike pattern, running speed, and footwear condition in recreational distance runners. Sports Biomechanics, 16(2), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2016.1226381

- Lieberman, D. E., Venkadesan, M., Werbel, W. A., Daoud, A. I., Dandrea, S., Davis, I. S., Mangeni, R. O., & Pitsiladis, Y. (2010). Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature, 463(7280), 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE08723

- Udofa, A. B., Clark, K. P., Ryan, L. J., & Weyand, P. G. (2019). Running ground reaction forces across footwear conditions are predicted from the motion of two body mass components. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 126(5), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00925.2018

- Jenkins, D. W., & Cauthon, D. J. (2011). Barefoot Running Claims and Controversies: A Review of the Literature. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 101(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.7547/1010231

- Rothschild, C. (2012). Running barefoot or in minimalist shoes: Evidence or conjecture? Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34(2), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0B013E318241B15E

- Altman, A. R., & Davis, I. S. (2016). Prospective comparison of running injuries between shod and barefoot runners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(8), 476–480. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2014-094482

- Udofa, A. B., Clark, K. P., Ryan, L. J., & Weyand, P. G. (2019). Running ground reaction forces across footwear conditions are predicted from the motion of two body mass components. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 126(5), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00925.2018

- Altman, A. R., & Davis, I. S. (2016). Prospective comparison of running injuries between shod and barefoot runners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(8), 476–480. https://doi.org/10.1136/BJSPORTS-2014-094482

- Murphy, K., Curry, E. J., & Matzkin, E. G. (2013). Barefoot Running: Does It Prevent Injuries? Sports Medicine 2013 43:11, 43(11), 1131–1138. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-013-0093-2

- McCarthy, C., Fleming, N., Donne, B., & Blanksby, B. (2015). Barefoot running and hip kinematics: good news for the knee? Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 47(5), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000505

- Davis, I. S., Hollander, K., Lieberman, D. E., Ridge, S. T., Sacco, I. C. N., & Wearing, S. C. (2021). Stepping Back to Minimal Footwear: Applications Across the Lifespan. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 49(4), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000263

- Quinlan, S., Sinclair, P., Hunt, A., & Yan, A. F. (2022). The long-term effects of wearing moderate minimalist shoes on a child’s foot strength, muscle structure and balance: A randomised controlled trial. Gait & Posture, 92, 371–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GAITPOST.2021.12.009

- Shakoor, N., Lidtke, R. H., Wimmer, M. A., Mikolaitis, R. A., Foucher, K. C., Thorp, L. E., Fogg, L. F., & Block, J. A. (2013). Improvement in knee loading after use of specialized footwear for knee osteoarthritis: results of a six-month pilot investigation. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 65(5), 1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ART.37896

- Trombini-Souza, F., Fuller, R., Matias, A., Yokota, M., Butugan, M., Goldenstein-Schainberg, C., & Sacco, I. C. N. (2012). Effectiveness of a long-term use of a minimalist footwear versus habitual shoe on pain, function and mechanical loads in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-13-121

- Brüggemann, G.-P., Potthast, W., Braunstein, B., & Niehoff, A. (n.d.). (PDF) Effect of increased mechanical stimuli on foot muscles functional capacity. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228326470_Effect_of_increased_mechanical_stimuli_on_foot_muscles_functional_capacity

- Russell, R., & Simmons, S. (2016). THE EFFECTS OF BAREFOOT RUNNING ON OVERPRONATION IN RUNNERS. International Journal of Exercise Science: Conference Proceedings, 8(4). https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijesab/vol8/iss4/42

- Jones, B. H., Toner, M. M., Daniels, W. L., & Knapik, J. J. (2007). The energy cost and heart-rate response of trained and untrained subjects walking and running in shoes and boots. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/00140138408963563, 27(8), 895–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140138408963563

- Fuller, J. T., Thewlis, D., Buckley, J. D., Brown, N. A. T., Hamill, J., & Tsiros, M. D. (2017). Body Mass and Weekly Training Distance Influence the Pain and Injuries Experienced by Runners Using Minimalist Shoes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(5), 1162–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516682497