There are two main philosophies when it comes to developing your biceps.

On one side, you have bodybuilder-types who spend an entire workout each week training their arms with curls of all kinds. This, they say, is the only way to build impressive guns.

On the other side, there are strength athletes and “fitness minimalists” who say all biceps exercises are boondoggles. In their book, you just need to do a few sets of barbell pulling exercises per week to add size to your “bis.”

Who’s right?

Should biceps exercises have a place in your training, or are pulling exercises enough?

Here’s what science says.

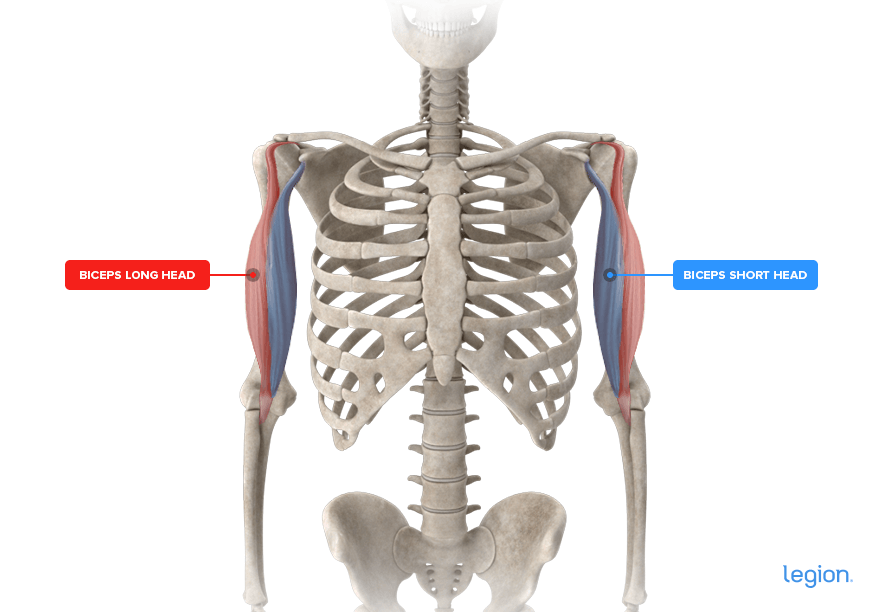

Biceps Anatomy

The biceps brachii, more commonly referred to as the biceps, is a two-headed muscle located on the front of the upper arm, between the shoulder and elbow.

Its main functions are elbow flexion (bending your elbow to bring your hand to your shoulder) and forearm supination (twisting your forearm, so your palm faces upward), though it also plays a smaller role in shoulder flexion (lifting your arm from by your side to above your head).

Here’s how the muscle looks:

People commonly train their biceps with isolation exercises, such as the barbell, dumbbell, and preacher curl. These exercises are effective at training your biceps because they allow you to flex your elbow against external resistance.

However, compound pulling exercises, including pull-ups, pulldowns, and rows, also train elbow flexion, which is why some people think these exercises are all you need to develop your biceps.

In other words, they think you can remove all biceps isolation exercises from your program so long as it already includes plenty of pulling exercises, which could shave a significant amount of time off some of your workouts or allow you to drop your biceps workout each week altogether.

It’s an interesting stance, but does science agree?

Do Pull-ups and Lat Pulldowns Work Your Biceps?

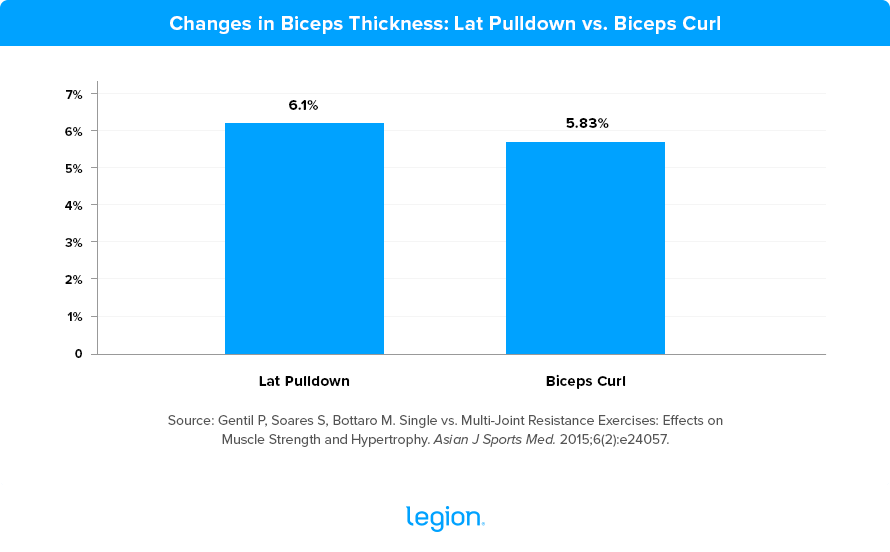

To answer this question, researchers at the University of Brasilia had 29 untrained men perform 3 sets of 8-to-12 reps to failure (the point at which you can’t complete a rep despite giving maximum effort) of either the lat pulldown or biceps curl twice weekly for 10 weeks.

(The participants in this study didn’t perform the pull-up. That said, the pull-up and lat pulldown are very similar exercises and train your biceps comparably. Therefore, we can likely use the results of this study to understand whether the pull-up also trains your biceps as effectively as the biceps curl.)

The results showed that both groups gained about the same amount of muscle and strength. Here’s a graph to illustrate the difference in muscle size:

These results show that the lat pulldown (and thus probably the pull-up) trains your biceps just as well as the biceps curl, which raises the question, is there any reason to do pulldowns and curls in your program?

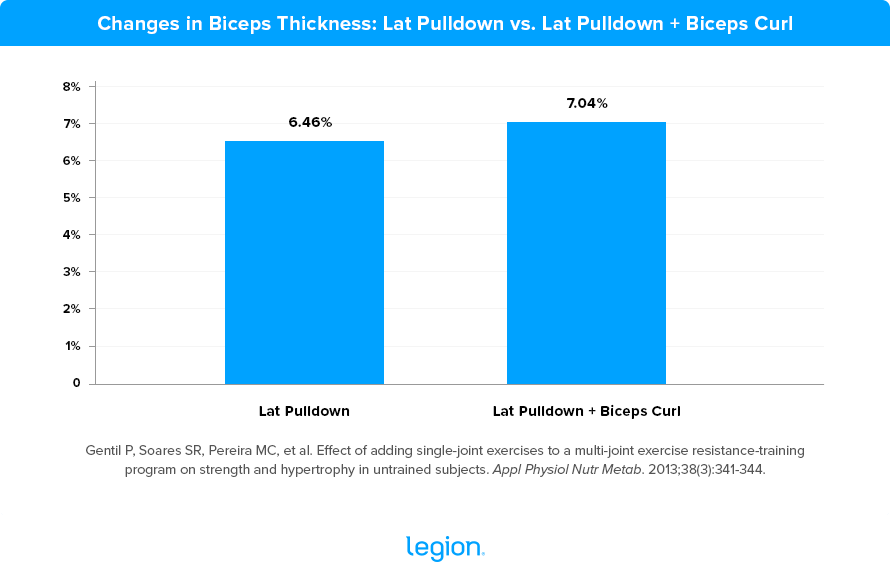

A previous study from the same research group offers an answer.

In this study, the scientists had another 29 untrained men do 3 sets of 8-to-12 reps to failure of either the lat pulldown or the lat pulldown and biceps curl twice weekly for 10 weeks.

This meant that the participants who performed the lat pulldown and biceps curl did around twice as much biceps volume (sets and reps) as the group that did the lat pulldown only. This is important because, to a point, the more volume you do for a muscle group, the more it grows.

Again, the results showed no significant difference between the groups regarding muscle and strength gain. Here’s a graph illustrating the difference in muscle size:

There’s one major caveat to consider with this study: The participants were completely new to weightlifting. This is relevant because new weightlifters require very little volume to make progress.

Thus, it’s possible that doing three sets of the lat pulldown twice weekly was enough to make these newbies’ biceps grow, and doing additional sets of biceps curls was superfluous or “junk” volume (extra sets and reps that produce little-to-no additional gains).

If the researchers had studied more experienced weightlifters, however, the results may have been different. That’s because the more advanced you are, the more resistant your muscles become to the muscle-building effects of weightlifting, and the more you benefit from higher training volumes.

This proviso aside, though, both studies show that doing biceps isolation exercises do little to aid biceps growth if you’re new to weightlifting, provided you already do plenty of vertical pulling exercises (exercises that involve pulling a weight toward your torso from above your head) each week.

What’s more, even once you have more weightlifting experience under your belt, it’s possible that you might get similar results by simply doing more sets of pulling exercises than if you did biceps curls.

Do Rows Train Your Biceps?

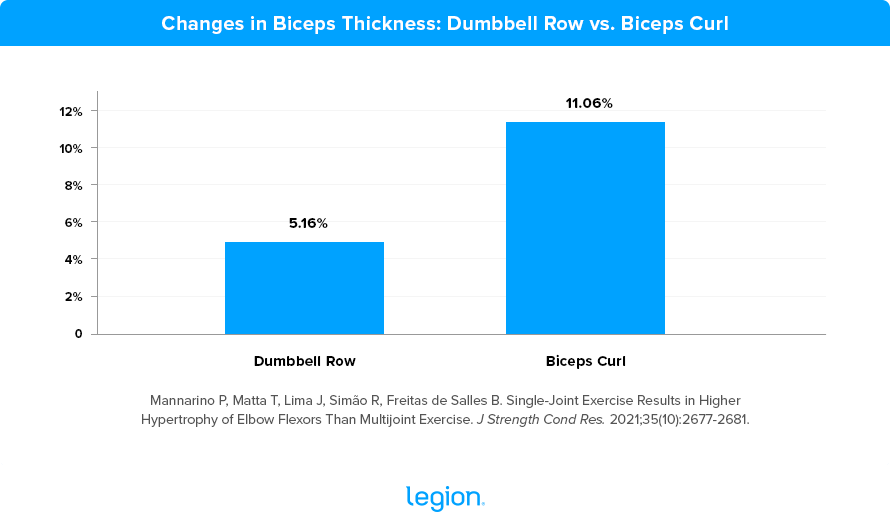

In a study conducted by scientists at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, researchers had 10 untrained men train one side of their body with the one-arm dumbbell row and the other with the biceps curl twice weekly for 8 weeks.

For the first 4 weeks, the participants did 4 sets of 8-to-12 reps of each exercise per workout, and in the final 4 weeks, they did 6 sets of 8-to-12 reps of each exercise per workout.

The results showed that doing rows caused less than half as much biceps growth as curls. Here’s a graph illustrating this point:

If growing your biceps is a top priority, you probably shouldn’t rely solely on horizontal pulling exercises (exercises that involve pulling a weight toward your torso from in front of you), which includes dumbbell rows, barbell rows, and cable rows.

These exercises do still train your biceps, but not quite as thoroughly as biceps isolation exercises like curls.

What’s the Best Way to Train Your Biceps?

At this point, you may be tempted to abandon direct biceps training altogether. After all, the studies we’ve reviewed thus far suggest it offers little in the way of extra biceps growth, provided you already do plenty of pulling each week.

This would probably be a mistake, though.

Biceps isolation exercises may not drastically boost muscle growth (especially not over a 10-week study), but they contribute a little, which would likely become meaningful over a longer period, especially once you’ve got several months or years of training under your belt. And when you consider how little time and energy they require, doing a few sets per week is a small price to pay for these long-term gains.

They also allow you to train your biceps when it’s no longer practical to do so with a compound exercise. For instance, your lats, traps, and rhomboids will probably be bushed after several sets of pulling exercises, but your biceps may be comparatively fresh. Training them with a few sets of curls ensures they’re adequately stimulated, which is vital to maximize growth.

Furthermore, biceps exercises make it easy to train your biceps in different positions and through different ranges of motions, which likely produces more balanced and complete muscle growth than training them with just 2 or 3 pulling exercises.

Another perfectly valid reason to include biceps exercises in your program is that they’re fun, and enjoyable and engaging workouts are typically more productive than boring ones.

With that said, I think the best way to train your biceps is to make compound pulling exercises the focus of your workouts, then “top off” your biceps volume with biceps isolation exercises that eke every last drop of muscle and strength gain out of your training.

The best way to put this into practice is to do two workouts per week that train your biceps: one pull workout that you do early in the week and one upper-body workout that you do later in the week that emphasizes your arms.

This is the way I like to organize my own training and the approach I advocate in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger.

Here’s an example of how the pull workout might look:

Deadlift: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

One-Arm Dumbbell Row: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Lat Pulldown: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Alternating Dumbbell Curl: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

And here’s an example upper-body workout that emphasizes your arms:

Pull-up: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Close-Grip Bench Press: 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Barbell Curl: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Triceps Pushdown: 3 sets of 6-to-8 reps with 2-to-3 min rest

Scientific References +

- Landin, D., Thompson, M., & Jackson, M. R. (2017). Actions of the Biceps Brachii at the Shoulder: A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 9(8), 667. https://doi.org/10.14740/JOCMR2901W

- Gentil, P., Soares, S., & Bottaro, M. (2015). Single vs. Multi-Joint Resistance Exercises: Effects on Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5812/ASJSM.24057

- Bauermeister, M. S. (1996). An EMG Comparison of Muscle Recruitment Associated with the Wide Grip Pull-Up and the Lat Pull-Down Exercise. 4493. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theseshttps://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4493

- Hewit, J. K., Jaffe, D. A., & Crowder, T. (2018). J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports A Comparison of Muscle Activation during the Pull-up and Three Alternative Pulling Exercises. J Phy Fit Treatment & Sportsl, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.19080/JPFMTS.2018.05.555669

- Gentil, P., Soares, S. R. S., Pereira, M. C., da Cunha, R. R., Martorelli, S. S., Martorelli, A. S., & Bottaro, M. (2013). Effect of adding single-joint exercises to a multi-joint exercise resistance-training program on strength and hypertrophy in untrained subjects. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition et Metabolisme, 38(3), 341–344. https://doi.org/10.1139/APNM-2012-0176

- E R Helms, P J Fitschen, A A Aragon, J Cronin, & B J Schoenfeld. (n.d.). Recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: resistance and cardiovascular training - PubMed. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24998610/

- Mannarino, P., Matta, T., Lima, J., Simão, R., & Freitas de Salles, B. (2021). Single-Joint Exercise Results in Higher Hypertrophy of Elbow Flexors Than Multijoint Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(10), 2677–2681. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003234

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- De Vasconcelos Costa, B. D., Kassiano, W., Nunes, J. P., Kunevaliki, G., Castro-E-Souza, P., Rodacki, A., Cyrino, L. T., Cyrino, E. S., & Fortes, L. D. S. (2021). Does Performing Different Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Induce Non-homogeneous Hypertrophy? International Journal of Sports Medicine, 42(9), 803–811. https://doi.org/10.1055/A-1308-3674