Key Takeaways

- Eating back the calories you burn during exercise is unnecessary and usually just slows weight loss.

- Most of the methods people use to calculate how many calories they burn during exercise overestimate their actual calorie burn, which can lead people to eat more than they should.

- Keep reading to learn why “eating back” the calories you burn from exercise is unnecessary and even counterproductive, and what you should do instead.

If you want to lose weight, one of the most helpful things you can do is start tracking your calorie intake.

This improves your awareness of how much you’re eating, where you can cut back, and how to budget your calories so as to eat your favorite foods while still losing weight.

Many people take this a step further and start tracking their calorie expenditure (“burn”) using an activity tracker like a FitBit, Apple Watch, or Jawbone.

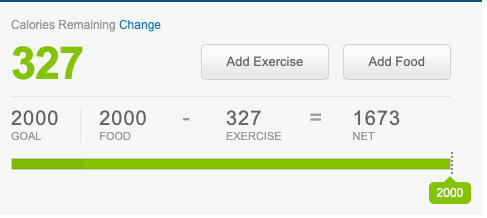

If you’ve used one of these trackers, though, you’ve probably noticed that on some days you burn a lot more calories than others. A hike, bike ride, or jog can jack up your calorie expenditure by several hundred calories, and when you plug this information into an app like MyFitnessPal, you’ll see something like this:

In this case, the person set a daily calorie budget of 2,000 calories, and they’d already eaten and tracked all of those calories. But they also went on a bike ride that burned 327 calories, which opens the question . . . should you “eat back” those ~300 calories?

Even if you don’t use an activity tracker, you’ve probably wondered the same thing: if you burn more calories on a particular day, should you eat more to compensate?

The short answer is that no, you probably shouldn’t eat back the calories burned during exercise.

If you want to know why this is the case and learn a better way to manage your calorie intake that doesn’t depend on activity trackers or constantly balancing your daily calorie budget in this way, keep reading.

Why You Shouldn’t Eat Back the Calories You Burn Exercising

The first problem with eating back the calories you burn during exercise is simple: if your goal is to lose weight, this is shrinking your calorie deficit, slowing your rate of weight loss.

Now, you may have heard that if you don’t eat back the calories you burn from exercise that you’ll put yourself in an excessively large calorie deficit. For example, if your normal diet puts you in a 500 calorie deficit, and you burn 250 more calories through exercise, that’s a 50% increase in your deficit (and rate of weight loss).

(Oh, and if you feel confused about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your weight-loss goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz to learn exactly what diet is right for you.)

While that’s a large relative increase in calorie burn compared to your normal deficit, it’s still a small absolute increase. That is, burning a few hundred more calories on one day isn’t going to cause any negative effects on your metabolism or health, and you may not even feel any hungrier than usual.

Basically, unless you’re already on the razor’s edge of low-calorie dieting, burning a few hundred more calories isn’t going to cause any issues.

Read: “Metabolic Damage” and “Starvation Mode,” Debunked by Science

The second problem with eating back the calories you burn during exercise is that if you set your calorie target properly (as explained in a moment), you should have already factored in the calories you burn from exercise. That is, you’re already getting “credit” for the calories you burn working out, so there’s no need to increase your calorie intake to compensate.

Finally, most people don’t know how to accurately estimate how many calories they burn during exercise. And when they overestimate this number, they eat more than they should.

The popularity of fitness trackers is partly to blame for this.

Although these tools give people the illusion of pinpoint accuracy, the reality is they only give you a rough estimate of how many calories you’re burning through formal exercise and other activities.

What’s more, most fitness trackers tend to work best at estimating the average number of calories you burn during a particular activity, like walking, but aren’t good for measuring much else.

Many of these devices are off by 50% or more (a fitness tracker might say you burned 300 calories during your walk, when you only burned 200 calories). Research also shows that most smartphone fitness tracking apps aren’t any better, and are often off by 30 to 50%.

Exercise machines that purport to measure your calorie burn tend to be the least accurate of any method. For example, a study conducted by researchers at the University of California-San Francisco’s Human Performance center found that, on average . . .

- Stationary bicycles overestimated by 7%.

- Stair-climbers overestimated by 12%.

- Treadmills overestimated by 13%.

- Elliptical machines overestimated by 42% (ooph).

Fitness trackers that use your heart rate to estimate your calorie burn tend to be more accurate than the others we’ve discussed, but the most accurate ones require you to wear an unwieldy strap around your chest (the wrist-based heart rate monitors tend to be less accurate).

The most accurate and practical method for calculating how many calories you burn during exercise is to use what’s called the Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) system. Although this system works well, it’s still not 100% accurate and is tedious to use on a daily basis.

You can learn more about the MET system and other methods for tracking your calorie intake in this article:

For all of these reasons, it’s not usually a good idea to try to “eat back” the calories you burn during exercise. If you want to lose weight, you’re just slowing your progress. If you compute your calorie needs correctly, it’s unnecessary. And even if there was value in eating back the calories you burn during exercise, you’re likely to overestimate the number and overeat as a result.

Summary: Eating back the calories you burn during exercise is unnecessary and counterproductive because it just slows weight loss and is difficult to do accurately.

What You Should Do Instead of Counting Calories Everyday

So if you shouldn’t eat back the calories from exercise, what should you do instead?

Well, part of the problem with this idea is that it assumes you should carefully micromanage your calorie intake and output on a daily basis. You burn a bit more and eat a bit more on Wednesday, you burn a bit less and eat a bit less on Thursday, and so on.

While this approach can work, it’s also tedious, time-consuming, and prone to error.

You inevitably waste time debating over what to eat, working out how much you can eat based on your activity levels, and you make mistakes, like forgetting to log every calorie, mistakenly logging more or less than you actually ate, or, as you learned above, overestimating how many calories you burned from exercise.

All of this is why I don’t recommend tracking calories “on the fly” in this manner. It’s simply not a viable long-term solution.

A better approach, and the one used by pretty much every bodybuilding coach, researcher, and athlete I know, is to estimate roughly how many calories you burn every day on average from all sources (including exercise). This number is known as your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE).

With this number in hand, you then set a calorie target that’s slightly less than this if you want to lose weight; more if you want to gain weight, and roughly equivalent if you want to maintain your weight.

And once you have your calorie target, you can create a proper meal plan that ensures you can hit your calorie and macro targets eating the foods you like. Then, losing weight becomes a simple process of sticking to your meal plan every day and adjusting your average calorie intake as needed based on how your body responds.

This system even works well if your energy expenditure fluctuates quite a bit from day to day. For example, if you enjoy vigorous cardio workouts, you might burn 1,000 or more calories from exercise several days per week, and only burn a few hundred on other days.

So long as you accurately calculate your TDEE, though, you don’t necessarily need to eat more on the days you work out and less on the days you don’t—you can just eat roughly the same amount every day with equally good results. (That said, there’s nothing wrong with cycling your calorie intake based on your activity levels if you want to go to the trouble—it’s just not necessary).

If you want to learn more about how to accurately estimate your TDEE and create effective fat loss meal plans, check out this article:

And if you don’t feel comfortable creating a meal plan of your own, we’d love to help you.

If you’re pretty flexible about what kinds of foods you like to eat, you want to check out our cutting meal plan templates for men and women. When you buy one of these plans, you get 10 pre-made meal plans with grocery lists, so you never get bored with your diet.

Click the links below to learn more:

If you have more specific dietary needs or wants, you want to check out our 100% custom meal plan service. When you buy this plan, you fill out a questionnaire with your fitness goals, food preferences, and everything else needed to create your plan. Then, one of Legion’s diet coaches uses this information to build a custom meal plan that perfectly suits your goals, preferences, and lifestyle.

Summary: Instead of tracking your calorie intake and expenditure every day, a better approach is to estimate your average daily calorie burn, and then create a meal plan based on this number to lose, gain, or maintain your weight.

The Bottom Line on Eating Back Exercise Calories

Once you learn the calculus of energy balance and how to track your calorie intake and expenditure, it’s logical to assume you should adjust how much you eat based on how much you burn each and every day.

That is, at first glance, it makes sense to “eat back” the calories you burn from exercise.

In reality, though, this is a tedious, time-consuming process that often just slows weight loss.

What’s more, if you calculate your calorie target properly (as explained in this article), the calories burned during exercise are already baked into your daily calorie goal.

Instead of tracking your calorie intake and expenditure every day, a better approach is to estimate your average daily calorie burn, and then create a meal plan based on this number to lose, gain, or maintain your weight.

Do that, and you’ll be able to control your body composition without the headache of counting calories every day.

What’s your take on eating back exercise calories? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Keytel, L. R., Goedecke, J. H., Noakes, T. D., Hiiloskorpi, H., Laukkanen, R., van der Merwe, L., & Lambert, E. V. (2005). Prediction of energy expenditure from heart rate monitoring during submaximal exercise. Journal of Sports Sciences, 23(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410470001730089

- UCSF. (n.d.). UCSF Human Performance Center featured on Good Morning America | UC San Francisco. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2010/02/3569/ucsf-human-performance-center-featured-good-morning-america

- Konharn, K., Eungpinichpong, W., Promdee, K., Sangpara, P., Nongharnpitak, S., Malila, W., & Karawa, J. (2016). Validity and reliability of smartphone applications for the assessment of walking and running in normal-weight and overweight/obese young adults. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 13(12), 1333–1340. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0544

- Cruz, J., Brooks, D., & Marques, A. (2017). Accuracy of piezoelectric pedometer and accelerometer step counts. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 57(4), 426–433. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06177-X

- Wallen, M. P., Gomersall, S. R., Keating, S. E., Wisløff, U., & Coombes, J. S. (2016). Accuracy of heart rate watches: Implications for weight management. PLoS ONE, 11(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154420