An “exercise non-responder” is a person who supposedly doesn’t get fitter, stronger, or healthier in response to working out.

Scientists have known for decades that not everyone reaps equal rewards from exercise (Pareto principle, perchance?), and that some people have to work twice as hard to get half the results of the next fellow.

Many bloggers, journalists, and fitness influencers have taken this a step further and claimed that some people don’t benefit from exercise at all, and that this is partly to blame for the spiraling health of people in Western countries.

Is this true, though, or a soothing scapegoat for people who struggle to lose weight, build muscle, and get fit?

Does exercise really just “not work” for some people?

And if so, how do you know if you’re one of these folks and what can you do about it?

What Is an “Exercise Non-Responder?”

There’s no scientific definition of what constitutes an “exercise non-responder,” but it generally refers to someone who experiences little or no benefit from working out.

For example, if someone starts training but fails to build muscle, get stronger, lose fat, improve their endurance, lower their blood pressure, etc., or benefits much less in these areas than most people, they might be labeled an “exercise non-responder.”

This definition is deceptive, though, because studies may mislabel people as exercise non-responders if they don’t improve one particular facet of their fitness, even if they improve other aspects.

Let’s say you participate in a 4-week study measuring how much muscle people gain in response to bench pressing. During the study, your strength and power shoot through the roof, your insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels improve, and you even lose some fat, but you don’t build much muscle (which is normal for such a short study).

Although you responded remarkably well to strength training, you could still be deemed an “exercise non-responder” because you didn’t improve in the metric the researchers cared about most.

That said, even if we set this semantic shortcoming aside, studies do show that some people don’t profit as much from exercise as others. That still doesn’t make them “non-responders,” though, but rather “low responders.”

Do Exercise Non-Responders Exist?

No, probably not.

Instead, it’s more accurate to say that some people are exercise “low-responders,” meaning they don’t benefit as much as most people do from the same training program, but the body of evidence shows that everyone can get some health and fitness benefits from working out.

What’s more, although some people may be low-responders to one kind of exercise, they may be high-responders to another.

Research shows that people respond differently to different kinds of exercise, and a program that works like gangbusters for one person may fall flat for another.

A salient example of this comes from research conducted by scientists at Merikoski Rehabilitation and Research Centre, where 73 participants completed two separate training programs: a cardio program and a weightlifting program.

Sure enough, some “non-responders” experienced almost no benefit from exercise. When the groups switched programs, the researchers found that the people who got the smallest gains from cardio got the biggest gains from weightlifting and vice versa. Thus, these supposed “non-responders” responded quite well to exercise when it was tailored to their unique physiology.

A follow-up study published in the Journal of Fitness Research also found that people who followed a workout plan geared toward their preferences and goals experienced much greater benefits than people who followed a cookie-cutter program. (And if you’d like a diet, training, and supplementation plan that’s perfectly personalized to your goals, preferences, and body, check out the Legion coaching program).

Another reason the term “exercise non-responder” is misleading is that research has shown time and time again that you can largely overcome this genetic handicap by training more or harder.

Researchers from the University of Zurich illustrated this in a study where they had people do either 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 one-hour cardio workouts per week. They found that about 70% of the people doing just one hour of cardio per week showed basically no improvement, and this fell to 40% of people doing two hours, 29% for people doing three hours, and 0% for people doing four or five hours. Basically, the more people worked out, the less likely they were to be a “non-responder.”

Most importantly, when they had the “non-responders” do just two more hours of cardio per week, everyone showed a significant improvement. As they put it, the “non-response is universally abolished” when the participants bumped up their training volume. Research shows that you can achieve similar benefits from upping your workout intensity, too.

This method works for weightlifting as well: people who respond poorly to a strength training program initially show a marked improvement by doing more sets.

Thus, while some people may be exercise “low-responders,” meaning they have to work harder than others to get similar results, there’s really no such thing as a “non-responder.” You can largely countervail crummy genetics with piss and vinegar.

As long as you do the right kind of exercise with the right volume, intensity, frequency, and duration, you will see benefits.

Your lifestyle also plays a major role in determining how well you recover from and ultimately respond to exercise.

Evidence of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at Queen’s University, where researchers had 10 men complete a 4-week high-intensity interval program. Once the participants had finished, the researchers categorized the men into low-, medium-, and high-responders based on how their muscles had adapted.

The participants then took a 3-month break from training before returning to the lab to redo the same 4-week workout program. After the participants had finished the program for a second time, the researchers measured how their muscles had responded and again sorted the men into low-, medium-, and high-responder groups.

If some people really have “bad” genetics for exercise, you’d expect the same “non-responders” from the first go around to be non-responders the second time, but this isn’t what happened. Instead, some people who were “non-responders” initially responded well to the same program after following it a second time, and some who responded well the first time saw little benefit the second time.

The most likely reason for this is that the participants’ lifestyles had changed. Your ability to recover from and adapt to your workouts is heavily influenced by your sleep quantity and quality, diet, stress levels, and so on, and a change in any of these variables can help or hurt your gains.

In other words, if you’re worried you might be an exercise “non-responder,” you might be surprised how well you respond to exercise if you start getting 7-to-9 hours of quality sleep per night, eating plenty of nutritious foods and sufficient calories and protein, and better managing your stress levels.

In the final analysis, the term “exercise non-responder” is inaccurate. While not everyone benefits from the same kind of exercise equally, everyone can benefit from some kind of exercise. The key is finding what works best for you.

(As an aside, this is also one of the reasons Mike includes so much flexibility in his programs for men and women. Following a program that’s tailored to your goals and preferences doesn’t just make getting fit more fun—it gets you better results.)

Are You an “Exercise Non-Responder?”

No, because exercise non-responders don’t really exist.

Although your DNA partially dictates how you respond to exercise, how you train, eat, and live has a much bigger impact. While you might have slightly suboptimal genetics for a particular kind of exercise than “average,” everyone can build a body they can be proud of with the right diet and training program.

Take muscle growth, for instance. While some people start out with much more muscle mass than others and also gain and maintain it more easily, I’ve never met a man who couldn’t gain at least ~20 pounds of muscle while eating and training properly, or a woman who couldn’t gain about half that amount.

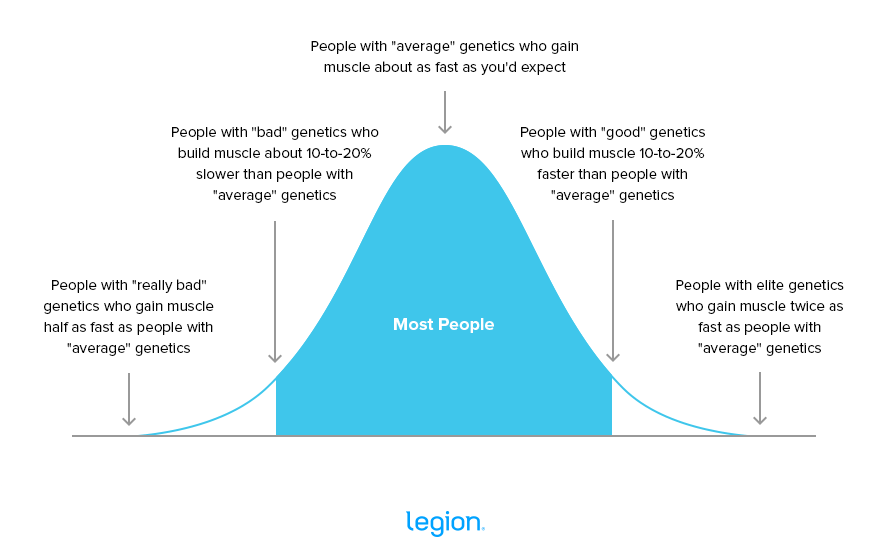

Here’s a helpful chart for visualizing this concept:

The people on the left of this bell curve can still build impressive physiques, it’ll just take them more time and effort than the folks in the middle or on the right.

A Note to “Hardgainers:” Don’t Write Yourself Off

The idea of exercise non-responders has been afloat in the fitness space for years, but under a different alias: “Hardgainers.” These folks believe they’re foredoomed to stay thin and small no matter how much they eat or how hard they train, and will argue up and down that there’s literally-no-way-I-can-possibly-gain-more-muscle-I-just-have-a-fast-metabolism-you-just-don’t-understand-bro.

The folks who write themselves off like this are always—yes, always—making glaring blunders with their diet and training: not eating enough, not training enough or training too much, not sleeping enough, and so on.

Instead of owning and correcting these mistakes, they pin the blame for their lackluster results on pseudoscientific labels like being a “hardgainer” or “exercise non-responder.”

Don’t be one of these dead ducks.

As Henry Ford once said, “Whether you think you can or you think you can’t, you’re right.” You can’t think your way through your genetic ceiling for muscle gain, of course, but adopt a fixed, pessimistic mindset, and you’ll guarantee that you never nudge it.

In other words, the person with “bad” genetics and a good attitude is almost certainly going to go farther than the person with “average” or even “good” genetics and a lousy headspace. And that’s true of a lot more than just muscle growth.

Focus on what you can control (diet, training, sleep, etc.), and don’t worry about the stuff you can’t (your genes).

How to Build Muscle if You’re a “Non-Responder”

If you’ve been training consistently for three months or more and you haven’t seen noticeable improvement in your strength, endurance, or whatever you’re trying to improve, it’s time to change your program, diet, or both.

Use these tips to right the ship.

1. Focus on progressive overload.

If you want to build muscle effectively, you have to strive to add weight or reps to every exercise in every workout.

This is known as progressive overload, and it’s one of the best ways to maximize the strength- and muscle-building effects of weightlifting.

The easiest way to do this is to use double progression—a method for increasing your weights only once you hit the top of your rep range for a certain number of sets (often one).

This is one of the best ways to ensure you use the right intensity in your workouts. Check out this article if you’d like to learn how to use it:

Double Progression Guide: How to Use Double Progression to Gain Muscle and Strength

2. Focus on heavy compound weightlifting.

A compound exercise is any exercise that trains several major muscle groups at the same time, like the squat, deadlift, and bench and overhead press.

Research shows that if you want to gain muscle and strength as fast as possible, nothing beats compound weightlifting, which is why it should be the focus of your training routine.

By “heavy,” I mean you need to focus on getting stronger over time on these exercises, and research shows the best way to do that is to lift weights that are 75-to-85% of your one-rep max (weights that you can do 6-to-12 reps with before your technique breaks down).

If you want a program that includes plenty of heavy compound weightlifting, check out this article (or one of Mike’s books for men and women):

The 12 Best Science-Based Strength Training Programs for Gaining Muscle and Strength

3. Do the right number of weekly sets.

To develop any major muscle group, it’s generally best to train it with 10-to-20 weekly sets.

Exactly where you program your workouts within this range comes down to your training experience, preferences, and goals, (having a good coach helps with this tremendously) but a good starting place is to shoot for 10-to-15 sets per muscle group if you’ve been training less than two years, and 15-to-20 sets per muscle group per week if you’ve been training for two or more years (and even then, it’s best to only do this much volume for one or two muscle groups at a time).

Check out this article to learn how to dial in your weekly training volume:

Volume vs. Intensity for Hypertrophy: Which Is More Important?

4. Eat enough calories and protein.

Most people (complete beginners excluded) need to maintain a mild calorie surplus to build muscle effectively.

Specifically, eating about 10% more calories than you burn every day optimizes your body’s “muscle-building machinery,” greatly enhancing your body’s response to training.

You also need to eat enough protein—about 0.8-to-1 gram per pound of body weight per day—to allow your muscles to recover, repair, and grow effectively, too.

If you’d like even more advice about how many calories, how much of each macronutrient, and which foods you should eat to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Diet Quiz. In less than a minute, you’ll know exactly what diet is right for you. Click here to check it out.

5. Take supplements proven to help you build muscle.

You don’t need to take any supplements to build muscle, but the right ones can help. (And if you’d like specific advice about exactly what supplements to take to reach your fitness goals, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz).

Here are the best supplements for supporting muscle growth:

- 0.8-to-1.2 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day. This provides your body with the “building blocks” it needs to build and repair muscle tissue and help you recover from your workouts. If you want a clean, convenient, and delicious source of protein, try Whey+ protein powder or Casein+ protein powder.

- 3-to-5 grams of creatine per day. This will boost muscle and strength gain, improve anaerobic endurance, and reduce muscle damage and soreness from your workouts. If you want a 100% natural source of creatine that also includes two other ingredients that will help boost muscle growth and improve recovery, try Recharge.

- One serving of Pulse per day. Pulse is a 100% natural pre-workout drink that enhances energy, mood, and focus; increases strength and endurance; and reduces fatigue. You can also get Pulse with caffeine or without.

Scientific References +

- Pickering, C., & Kiely, J. (2019). Do Non-Responders to Exercise Exist—and If So, What Should We Do About Them? Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 49(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-018-01041-1

- Montoye, A. H. K., Westgate, B. S., Clevenger, K. A., Pfeiffer, K. A., Vondrasek, J. D., Fonley, M. R., Bock, J. M., & Kaminsky, L. A. (2021). Individual versus Group Calibration of Machine Learning Models for Physical Activity Assessment Using Body-Worn Accelerometers. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 53(12), 2691–2701. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002752

- Ahtiainen, J. P., Walker, S., Peltonen, H., Holviala, J., Sillanpää, E., Karavirta, L., Sallinen, J., Mikkola, J., Valkeinen, H., Mero, A., Hulmi, J. J., & Häkkinen, K. (2016). Heterogeneity in resistance training-induced muscle strength and mass responses in men and women of different ages. AGE 2016 38:1, 38(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11357-015-9870-1

- Hautala, A. J., Kiviniemi, A. M., Mäkikallio, T. H., Kinnunen, H., Nissilä, S., Huikuri, H. V., & Tulppo, M. P. (2005). Individual differences in the responses to endurance and resistance training. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2005 96:5, 96(5), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-005-0116-2

- Dalleck, L., Haney, D. E., Buchanan, C. A., & Weatherwax, R. M. (n.d.). (PDF) Does a personalised exercise prescription enhance training efficacy and limit training unresponsiveness? A randomised controlled trial. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311536467_Does_a_personalised_exercise_prescription_enhance_training_efficacy_and_limit_training_unresponsiveness_A_randomised_controlled_trial

- Montero, D., Lundby, C., Montero, D., & Lundby, C. (2017). Refuting the myth of non-response to exercise training: ‘non-responders’ do respond to higher dose of training. The Journal of Physiology, 595(11), 3377–3387. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP273480

- Ross, R., De Lannoy, L., & Stotz, P. J. (2015). Separate effects of intensity and amount of exercise on interindividual cardiorespiratory fitness response. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(11), 1506–1514. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2015.07.024/ATTACHMENT/34AF53F8-A10B-4E9B-A6C3-A031E2EC8AF7/MMC2.MP4

- Hammarström, D., Øfsteng, S., Koll, L., Hanestadhaugen, M., Hollan, I., Apro, W., Whist, J. E., Blomstrand, E., Rønnestad, B. R., & Ellefsen, S. (2019). Benefits of higher resistance-training volume depends on ribosome biogenesis. BioRxiv, 666347. https://doi.org/10.1101/666347

- Islam, H., Bonafiglia, J. T., Del Giudice, M., Pathmarajan, R., Simpson, C. A., Quadrilatero, J., & Gurd, B. J. (2021). Repeatability of training-induced skeletal muscle adaptations in active young males. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 24(5), 494–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSAMS.2020.10.016

- Bamman, M. M., Petrella, J. K., Kim, J. S., Mayhew, D. L., & Cross, J. M. (2007). Cluster analysis tests the importance of myogenic gene expression during myofiber hypertrophy in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 102(6), 2232–2239. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.00024.2007

- Petrella, J. K., Kim, J. S., Mayhew, D. L., Cross, J. M., & Bamman, M. M. (2008). Potent myofiber hypertrophy during resistance training in humans is associated with satellite cell-mediated myonuclear addition: a cluster analysis. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 104(6), 1736–1742. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.01215.2007

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181E840F3

- Gentil, P., Soares, S., & Bottaro, M. (2015). Single vs. Multi-Joint Resistance Exercises: Effects on Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5812/ASJSM.24057

- Marx, J. O., Ratamess, N. A., Nindl, B. C., Gotshalk, L. A., Volek, J. S., Dohi, K., Bush, J. A., Gómez, A. L., Mazzetti, S. A., Fleck, S. J., Häkkinen, K., Newton, R. U., & Kraemer, W. J. (2001). Low-volume circuit versus high-volume periodized resistance training in women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(4), 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200104000-00019

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Stokes, T., Hector, A. J., Morton, R. W., McGlory, C., & Phillips, S. M. (2018). Recent Perspectives Regarding the Role of Dietary Protein for the Promotion of Muscle Hypertrophy with Resistance Exercise Training. Nutrients, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/NU10020180

- Branch, J. D. (2003). Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(2), 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.13.2.198

- Eckerson, J. M., Stout, J. R., Moore, G. A., Stone, N. J., Iwan, K. A., Gebauer, A. N., & Ginsberg, R. (2005). Effect of creatine phosphate supplementation on anaerobic working capacity and body weight after two and six days of loading in men and women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(4), 756–763. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-16924.1

- Bassit, R. A., Pinheiro, C. H. D. J., Vitzel, K. F., Sproesser, A. J., Silveira, L. R., & Curi, R. (2010). Effect of short-term creatine supplementation on markers of skeletal muscle damage after strenuous contractile activity. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00421-009-1305-1