“[CELEBRITY TRAINER]’s Latest Fat-Melting Workout!”

“8 Moves for Rock-Hard Abs!”

“How [FAMOUS MOVIE STAR] Got Ripped For [MOVIE]!”

I used to think fitness magazines were for genuine education.

I bought a stack every month and perused them page by page, looking for insights, tips, and tricks.

That’s me after nearly 7 years of jumping from one magazine’s workout program to another.

Well, I finally came to my senses and realized fitness magazines are more for entertainment than edification. So I turned my back on the newsstand and went off to learn how dieting really works, how to train effectively, and how to stop wasting hundreds of dollars per month on worthless supplements.

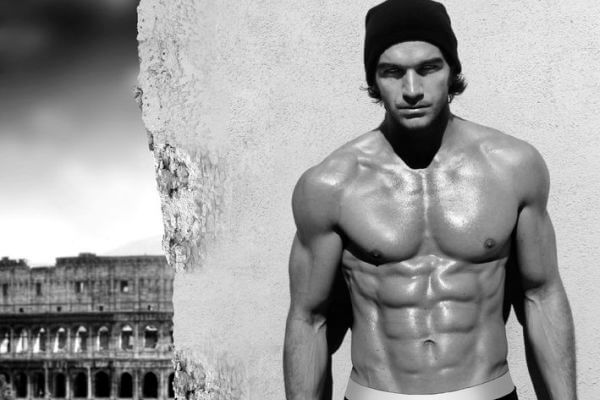

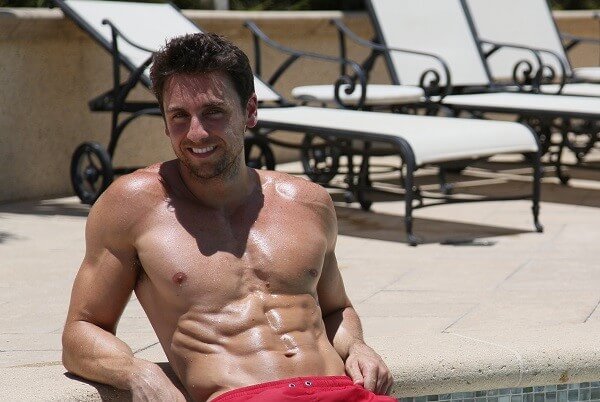

And the results were staggering. Here’s me, about 3 years later:

I want you to be able to tell the same story.

That’s why I write articles like this, books like these, and spend hours every day (freely) answering people’s questions.

Now, let’s talk a bit more about fitness magazines.

I don’t think their editors and publishers are evil scum. They’re just people faced with a dilemma

Table of Contents

+The first problem magazines face is the nature of their business: selling information.

Magazines need to keep people buying and subscribing every month. What do you think is the best marketing button to push to accomplish this?

New.

The easiest way to keep people hooked is to continually give new advice–new training methodologies, diet “tricks,” supplement research, and the like.

This isn’t bad per se. Health and fitness are vast subjects with myriad tunnels, caverns, and trails to explore. Most of it won’t sell magazines though.

Your average guy or gal isn’t nearly as interested in the nuances of training periodization as how to lose belly fat. How to change your body weight set point versus how to build bigger arms…which do you think makes for a better magazine cover?

This is why Men’s Health stopped writing new cover lines years ago.

They know their target market wants, more than anything else, abs, bigger arms and a bigger chest, and more sex, money, confidence, intelligence, and health.

Hence, the endless repetition of cover lines like “Six-Pack Abs!” “Dress For More Sex!” and “Build Wealth Fast!” and the endless supply of rehashed…er…re-imagined…articles to go with them.

The truth, however, is it doesn’t take 13 different articles to teach someone how to get six-pack abs or bigger arms or even their “best body ever.”

If magazines told the simple truth every month, they would have maybe 20 articles that they could reprint, verbatim, over and over. And that’s a horrible plan for an information subscription business.

And, to be honest, the articles wouldn’t be terribly exciting. They might have titles like…

How to Build 15 Pounds of Muscle In Your First Year

Move More, Eat Less–The “Secret” to Weight Loss

Why the Most Popular Bodybuilding Supplements Do Nothing

That is, they would teach you “inconvenient truths” like you can’t build muscle as fast as you’d like…you can’t target belly fat for elimination..and you’ll need more than twelve 50-word tips to build the body of your dreams.

It all boils down to diligent and consistent application of the fundamentals and it takes time. The sooner you accept these realities the sooner you can start making real progress.

The second problem magazines face is the nature of their revenue: advertising.

Many of the mainstream fitness magazines are little more than mouthpieces for supplement companies, which either own them outright or control them financially through advertising spend.

If these magazines are to stay in business, they must provide their supplement advertisers with a return on investment, and they’ve gotten really good at it.

They push supplements in various ways: pretty advertisements, “advertorials” (advertisements disguised as informative articles), and “soft-sell” articles that provide workout and nutrition advice that include supplement recommendations.

Thus, much of what you’re “learning” in magazines is geared toward selling you products, not actually helping you achieve your goals as efficiently as possible.

“But wait,” you might be thinking, “don’t supplements help me reach my goals?”

Well, the long story short is most supplements are a complete waste of money and will do absolutely nothing to help you build muscle or lose fat.

Don’t believe for a second that these pills and powders do anything special for the shredded bodybuilders and fitness models hawking them. If you knew the sheer amount of drugs many of these people are on, your head would spin. Their bodies are basically chemistry experiments.

So, as long magazine publishers keep getting their shlock into people’s hands, supplement companies will keep paying and all will be right in the world. This, then, brings us back to problem #1: how to keep selling magazines. And so the vicious cycle continues.

So, now that you know a bit more about the fitness magazine game, let’s move on to the meat of this article: the 7 biggest lies they tell to keep people buying, trying, and failing.

Fitness Magazine Lie #1:

“Ab Workouts” Give You Abs

If there’s one thing that keeps fitness-minded people up late at night Googling, wallet in hand, it’s the quest to get “six-pack abs.”

You may be strong…you may be big…but all the cool kids have killer abs. And just about everyone wants in on the party.

The problem, however, is the sheer amount of awful, misleading, and downright detrimental “six-pack” advice out there.

- Some people say you just have to do special types of ab workouts every day…and they’re wrong.

- Some people say you should just squat and deadlift and you’ll have great abs…and they’re wrong.

- Some people say you have to eat certain types of foods and not eat others…and they’re wrong.

- Some people say you just have to have a low body fat percentage…and they’re wrong.

- And some people say it’s all in the supplements…and they’re just lying.

The reality is you have to do just two things to have great abs:

You see, the first thing you need to know is this:

The main reason you don’t have abs is you have too much fat covering them.

This isn’t exactly news to most people…but…what they don’t know is just how lean you have to be to have a clearly visible six pack.

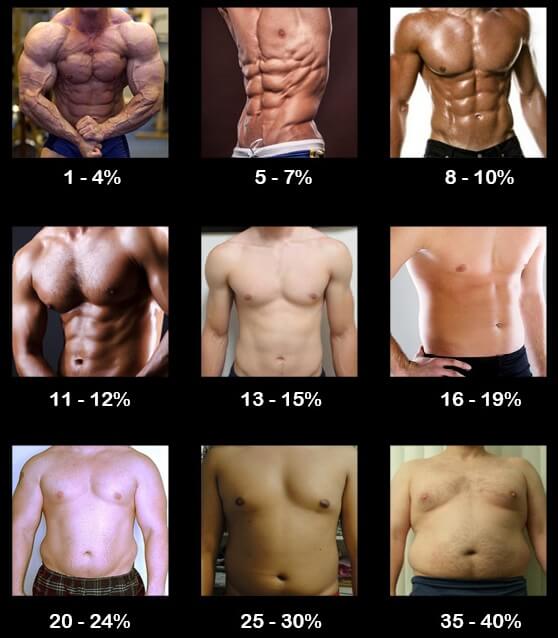

Well, the rule of thumb is the abs really start to become visible at 10% body fat and under in men and 20% and under in women. And the “shredded” look starts at ~7% and under in men and ~15% and under in women.

If you’re not familiar with how various body fat percentages look, these images will help:

So, step one is get lean and you’ll have abs. But not necessarily great abs, which is where building your core comes in. And, like most things health and fitness, this is made to seem much more complicated than it actually is.

There are an almost endless variety of ab exercises and far too many opinions on what’s better than what. Fortunately, however, you only need to focus on a handful of to fully develop your core.

Fitness Magazine Lie #2:

Here’s How So-and-So Got Ripped for Their Movie

Evans in Captain America, Cavill in Man of Steel, Hemsworth in Thor, Jackman in X-Men, Pitt in Troy, Bale in Batman, Butler in 300.

Ever year some new stud pops up on the silver screen with a body that makes the gals swoon and the guys re-up their gym memberships. And the magazines have a field day.

Covers get Photoshopped, workouts that the stars didn’t do get invented, and supplements they didn’t take get hawked.

Well, let’s cut the bullshit and get right the point: when you hear of a guy gaining 30 pounds of muscle in 4 months, the first thing you should suspect is steroids.

I know, I know…people love to cry steroids when they see someone in better shape than them, but hear me out.

Research shows that a guy new to weightlifting can expect to gain anywhere from 15 to 20 pounds of muscle in his first year of weightlifting. (And for women, cut those numbers in half.)

And that’s assuming he’s/she’s following a well-designed training program and diet. Anything less will deliver less results.

The same research shows that in year two, he can expect about half of the year one gains (8 to 10 pounds in men and half in women). Year three, half again. And from year four on out, anywhere from 2 to 5 pounds per year.

Yes, natural muscle growth really does take that long.

That’s why it usually takes 3 to 5 years for guys and gals to gain the 35 to 45/15 to 20 pounds of muscle required to naturally transform their physiques from “normal” to “fitness model.”

Now, how do these projections change when steroids are added to the picture?

Well, let’s first look at an extensive review of anabolic steroid use conducted by scientists at Maastricht University. They found that experienced weightlifters using anabolic steroids were able to gain between 4.5 and 11 pounds of muscle in less than ten weeks. The largest amount of muscle growth they saw was 15.5 pounds over 6 weeks of steroid-fueled weightlifting.

Those are some pretty outrageous numbers that could never be replicated naturally.

Another study that lends insight to the power of steroids was a case study conducted with an elite bodybuilder. Researchers followed him for a year, and he used steroids for all but 4 weeks of the 12-month period. By the end of the year, he had gained about 15 pounds of muscle, or about triple the amount that he should have been able to gain naturally.

So, now that you know how much steroid use affects muscle growth, let’s get back to actors training for movie roles.

The most obvious red flag is the how quickly they get fit and how dramatically their bodies change.

It’s common to hear about so-and-so going from a dad bod to gaining 20+ pounds of muscle in a few months while staying lean, or even reducing body fat.

Some of these guys have muscle memory on their side but that’s just not enough to put up results like that. You can bet that drugs were involved.

Now, did the guys I named earlier do this? I don’t know. But I don’t know why they wouldn’t have. Think about it for a second.

Most actors aren’t gym rats that stay jacked throughout the year and they have some really good reasons to use steroids to secure a role.

Millions of dollars and, often, a career jump are on the line, results are needed very quickly, and world-class bodybuilding coaches and doctors are available to ensure everything is done properly.

Hell, who can blame them really? Can you really say you wouldn’t do the same thing if you were in the same position?

So, my point here isn’t to call out anyone in particular or even speak badly of Hollywood folk that use steroids to prep for movies. I could care less what people do with their bodies.

It’s unfortunate, however, that their transformations are used to sell people on diets and workout routines that simply won’t work without the drugs.

When you hear that so-and-so lifted weights for 2+ hours per day, 7 days per week, and then did conditioning work on top of that…and ate thousands of calories per day…and came out bigger, leaner, and stronger than ever in just 3 months…just know what you’re looking at.

Fitness Magazine Lie #3:

This Supplement Changes Everything

Let’s start out by making something abundantly clear:

There is no single supplement that is going to make a dramatic difference in your training, muscle growth, or fat loss.

A combination of the right supplements can help you reach your goals faster, but you can get there smart dieting and training alone.

The truth is most workout supplements are completely bogus and can’t deliver a fraction of the results they promise. They are, for a lack of better terms, worthless crap.

Oh can they make money, though. A lot of freaking money. And as you know, magazines have a big stake in those numbers growing.

Well, don’t buy into it. Here are the most common types of supplement bullshit:

- Anything other than creatine that is claimed to directly help you build muscle and strength…

- Anything that is claimed to rapidly increase fat loss…

- Anything that claims to naturally boost your testosterone levels…

…is bullshit.

If you’d like to know more about which supplements work and which don’t, and about supplementation in general, check this out.

Fitness Magazine Lie #4:

Cardio is a Great “Fat Loss Workout”

Every morning I see the same crowd of overweight people grinding away and gushing sweat on the treadmill, StairMaster, and elliptical machines, which I imagine they’ve reserved and named by now.

And these guys and gals are just as fat as they ever were. Some are even fatter than when they started, which begs the question of what they think is going to change.

Well, they’re just stuck following decades of bad weight loss advice centered around doing long hours of cardio, which has produced millions of overtrained, overweight, underfit people addicted to burning calories instead of getting fit.

This isn’t just my opinion, either. Research shows that just doing regular cardio guarantees little in the way of fat loss and many people wind up even fatter than when they began their exercise routines.

There are several reasons why cardio isn’t all that great for losing fat.

It’s too easy to eat the calories you burn.

You have to work damn hard just to burn a few hundred calories in a cardio workout…and it’s really damn easy to eat them all back without even realizing it. A couple handfuls of nuts and some fruit is all it takes.

The energy you burn during cardio does support your weight loss efforts, of course, but your goal isn’t to just burn calories, it’s to lose fat. And if you’re eating too much, no amount of cardio is going to get you leaner.

Your body adapts to the exercise to reduce caloric expenditure.

If someone at least halfway informed stops losing weight, she will rightly suspect the problem is overeating.

What she probably won’t suspect, though, is the adaptive aspect of exercise.

Research shows that the more frequently you do a certain type of activity, the more your body adapts to increase energy efficiency. This means that, as time goes on, less and less energy is needed to continue doing it.

This can throw people for a loop because it leads them to believe they’re burning more calories doing cardio than they actually are.

This, then leads them to eat too much food, fail to lose weight, and then wonder what the hell is wrong. Metabolic “damage”? Thyroid problems? Genetic curse?

Many people stuck in this quandary refuse to give up, though, and do the only thing they know: more cardio. This “fight fire with fire” approach does increase overall caloric expenditure but also accelerates metabolic slowdown and brings various health risks into play.

The right way to look at cardio and weight loss is this:

The less cardio you can do while still reaching your body composition goals, the better.

Check out this article to learn how to do this.

Cardio doesn’t preserve muscle, which is just as important as losing fat.

We say we want to lose weight but what we really want is to lose fat.

This isn’t pedantry.

Losing weight includes losing muscle, which is what you can expect when you restrict your calories and do a lot of cardio, and which is what causes the “skinny fat” look.

The key here is including resistance training in your regimen, which speeds up fat loss and helps minimize muscle loss. In fact, when you’re dieting for fat loss, I recommend that you do 2 to 3 times as much resistance training as cardio.

The Bottom Line on Cardio Workouts and Weight Loss

Cardio can help you lose fat faster but it just doesn’t deserve all the attention it gets.

I’ve already mentioned that I do no more than a couple hours of cardio per week when cutting, and here’s how I go about it.

Fitness Magazine Lie #5:

You Have to “Eat Clean” to Get Fit

The cult of “clean eating” is more popular than ever these days. And while it has its heart in the right place, it really misses the forest for the trees.

What most “clean eaters” don’t realize is the nutritional value of food has little to do with its effect on your body composition.

There’s no questioning that you need to eat plenty of nutritious foods to stay healthy, but there are no foods that directly cause weight loss or weight gain.

Sugar isn’t your enemy and “healthy fats” aren’t your savior.

The key to understanding these “blasphemous” statements is understanding the concept of “energy balance,” which is the relationship between the amount of energy you eat and the amount you burn.

The immutable reality is meaningful weight loss requires eating less energy than you expend and meaningful weight gain requires the opposite (eating more than you burn).

You see, when you eat less energy than you burn, you’re in what’s known as a “negative energy balance” or “calorie deficit.” This results in weight loss. And when you eat more than you burn, you’re in a “positive energy balance” or “calorie surplus.” This results in weight gain.

Thus, in this sense, a calorie is a calorie.

Eat too many calories of the “cleanest” foods in the world and you will gain weight. Maintain a calorie deficit while following a “gas station diet” of the most nutritionally bankrupt crap you can find and you will lose weight.

This is why Professor Mark Haub was able to lose 27 pounds on a diet of protein shakes, Twinkies, Doritos, Oreos, and Little Debbie snacks. He simply ate fewer crappy calories than his body burned and, as the first law of thermodynamics dictates, this resulted in a reduction in total fat mass.

That said, a calorie is not a calorie when it comes to optimizing body composition, which is what we really want to do. Click here to learn why.

Fitness Magazine Lie #6:

Low-Carb Dieting is the Way of the Future

Dietary demagogues are leveling some pretty serious charges against the carbohydrate these days.

If we’re to buy into the hysteria, carbs make us fat, braindead, and diseased, and the sooner we forsake them, the better our chances for vitality, happiness, and longevity.

Well, that’s a bunch of hooey.

Unless you’re overweight and sedentary, carbohydrates aren’t the enemy. They don’t make you fat or unhealthy.

In fact, carbs are vitally important for building muscle and reducing your intake doesn’t help you lose fat faster.

Let’s first look at how eating carbs helps you build muscle.

How Carbs Help You Build Muscle

When you eat carbs, one of the substances they are broken down into is glycogen, which is a form of potential energy stored in the liver and muscles.

Resistance training is an anaerobic activity, which means it pulls heavily on muscle glycogen stores.

When your muscles are full of glycogen, which requires a rather high carb intake, they perform better and sustain less damage during training.

And when we look at the bigger picture of muscle growth, the importance of these benefits becomes clear.

The harder you can push your muscles in your workouts, the better you can progressively overload them over time…which increases muscle growth. And the less exercise-induced protein degradation there is, the greater the gap there will be between protein synthesis and breakdown rates…which increases muscle gain.

Another muscle-building benefit of a high-carb diet relates to insulin production.

Carb haters will tell you that the insulin “spike” that occurs when you eat carbs is one of the biggest reasons they’re so bad for you, but this is laughable.

First, insulin’s job is to shuttle nutrients from your blood into your cells. It’s vitally important and nothing to be afraid of.

Second, low-carb advocates usually extol the virtues high-protein dieting, which I agree with, but most forms of protein “spike” insulin production just as carbs do. For example, whey protein is more insulinogenic than white bread and eating beef causes just as much insulin to be released as brown rice.

They can’t have it both ways. You can’t say the insulin spike that occurs when you eat carbs is worse than the almost identical spike that occurs when you eat protein.

Now, what does all this have to do with building muscle?

Well, insulin doesn’t directly stimulate muscle growth like amino acids do, but it is anti-catabolic, which means it slows down the rate at which muscle proteins are broken down.

This affects muscle growth because, as mentioned earlier, anything that suppresses muscle protein breakdown rates is going to affect the “bottom line” of muscle proteins gained vs. lost is going to, over time, affect total lean mass gained or lost.

That’s not just theory, either. There are several studies that conclusively show that high-carbohydrate diets are superior to low-carbohydrate varieties for building muscle and strength.

Researchers at Ball State University found that low muscle glycogen levels (which is inevitable with low-carbohydrate dieting) impair post-workout cell signaling related to muscle growth.

A study conducted by researchers at the University of North Carolina found that when combined with daily exercise, a low-carbohydrate diet increased resting cortisol levels and decreased free testosterone levels.

(Cortisol, by the way, is a hormone that breaks tissues, including muscle, down. It’s also inversely correlated with testosterone, meaning that someone with chronically high cortisol levels is going to have chronically low levels of testosterone, which isn’t ideal for building muscle.)

These studies help explain the findings of other research on low-carbohydrate dieting.

For example, a study conducted by researchers at the University of Rhode Island looked at how low- and high-carbohydrate intakes affected exercise-induced muscle damage, strength recovery, and whole body protein metabolism after a strenuous workout.

The result was the subjects on the low-carbohydrate diet (which wasn’t all that low, actually—about 226 grams per day, versus 353 grams per day for the high-carbohydrate group) lost more strength, recovered slower, and showed lower levels of protein synthesis.

In this study, researchers at McMaster University compared high- and low-carbohydrate dieting with subjects performing daily leg workouts. They found that those on the low-carbohydrate diet experienced higher rates of protein breakdown and lower rates of protein synthesis, resulting in less overall muscle growth than their higher-carbohydrate counterparts.

All this is why I never drop my carbohydrate intake lower than about .8 grams per pound of body weight when cutting (and yes I get to 6% body fat eating this many carbs per day), and I’ll go as high as 2 to 2.5 grams per pound when bulking.

Why a Low-Carb Diet Isn’t Better for Losing Fat

That statement is fitness sacrilege these days, but the widely popular advice to go on a low-carb diet to maximize fat loss is scientifically bankrupt.

There are about 20 studies that low-carb proponents bandy about as definitive proof of the superiority of low-carb dieting for weight loss. This, this, and this are common examples. If you simply read the abstracts of these studies, low-carb dieting definitely seems more effective, and this type of glib “research” is what most low-carbers base their beliefs on.

But there’s a big problem with many of these studies, and it has to do with protein intake.

The problem is the low-carb diets in these studies invariably contained more protein than the low-fat diets. Yes, one for one…without fail.

What we’re actually looking at in these studies is a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-protein, high-fat diet, and the former wins every time. But we can’t ignore the high-protein part and say it’s more effective because of the low-carb element.

In fact, better designed and executed studies prove the opposite: that when protein intake is high, low-carb dieting offers no especial weight loss benefits.

But we’ll get to that in a minute.

Why is protein intake so important, exactly? Because adequate protein intake while dieting for fat loss is vital for preserving lean mass, both with sedentary people and especially with athletes.

If you don’t eat enough protein when dieting to lose weight, you can lose quite a bit of muscle, and this in turn hampers your weight loss in several ways:

1. It causes your basal metabolic rate to drop.

2. It reduces the amount of calories you burn in your workouts.

3. It impairs the metabolism of glucose and lipids.

As you can see, when you want to lose fat, your number one goal to preserve lean mass.

Now, let’s turn our attention back to the “low-carb dieting is better” studies mentioned earlier. In many cases, the low-fat groups were given less protein than even the RDI of .8 grams per kg of body weight, which is just woefully inadequate for weight loss purposes. Research has shown that even double and triple those (RDI) levels of protein intake isn’t enough to fully prevent the loss of lean mass while restricting calories for fat loss.

So, what happens in terms of weight loss when you keep protein intake high and compare high and low levels of carbohydrate intake? Is there even any research available to show us?

Yup.

There are four studies I know of that meet these criteria and gee whiz look at that…when protein intake is high and matched among low-carb and high-carb dieters, there is no significant difference in weight loss.

The bottom line is so long as you maintain a proper calorie deficit and keep your protein intake high, you’re going to maximize fat loss while preserving as much lean mass as possible. Going low-carb as well won’t help you lose more weight.

Fitness Magazine Lie #7:

Women Shouldn’t Lift Heavy Weights

If there’s one lie that causes more harm to women’s physiques than any other, it’s the warning that heavy weightlifting makes you “bulky.”

At first glance, it sounds plausible. Heavy weights are for the boys that want bulging biceps, right? Why would women, who want long, lean, “toned” muscles, train in the same way? Apparent proof of this myth can be found at any local CrossFit box, where you’ll see at least a few women with builds that would make a linebacker jealous.

Well, the first thing you should know it’s very hard for women to build a big, bulky body. It doesn’t happen by accident or overnight. It takes years of intense training and eating to look like a dyed-in-the-wool weightlifter.

Trust me–even if you wanted to get big, bulky muscles, you’d have a hell of a time actually doing it. Men have about 10 to 15 times as much testosterone as women and even we have trouble getting big and bulky. That means it’s damn near impossible for you.

This heavy weightlifting fallacy is so detrimental because heavy weightlifting is actually the only way to get the look most women are after: athletic, tight muscles with curves and lines in the right places.

If this is your goal, you’re going to have to build muscle, and heavy weightlifting is great for doing just that.

The key to building muscle and not “bulk,” however, is staying lean. The more muscle you have, the more you have to pay attention to your body fat percentage.

Take an athletic woman with an enviable body. You know, shapely legs, curvy butt, tight arms, and flat stomach. Add 15 pounds of fat to her frame, however, and you might be surprised how “blocky” she looks.

This is because fat accumulates inside and on top of muscles, and the more you have of both, the larger and more amorphous your body looks. Your legs turn into logs. Your butt gets too big for your britches. Your arms fill up like sausages.

Reduce your body fat levels, however, and everything changes–the muscle you’ve built is able to shine. Instead of looking flabby and malnourished, you look lean and toned. Your butt is round and perky. Your legs have sleek curves. Your arms look defined.

What types of body fat percentages am I talking about, you’re wondering?

If you want that lean, defined, athletic look, you’re going to need to maintain a body fat percentage between 15 and 20%.

I’ve worked with thousands of women and the “sweet spot” for most seems to be around 17 to 18%. This is where they can lift weights and build muscle and look both feminine and fit, and it isn’t so low that health or lifestyle is impaired.

The Bottom Line on Fitness Magazines

I could go on for another 10,000 words but I think I’ll end the assault here. I think I’ve made my point–much of what you read in magazines is just nonsense.

That said, fitness magazines aren’t all bad. Everything has its positives. I mean, even the demonic Third Reich gave us Volkswagon, Hugo Boss, the autobahn, and Wernher von Braun.

Just kidding.

To be fair, magazines do keep many people motivated to keep working out and inspire many more to pursue healthier lifestyles, but they should be viewed accordingly. Think dalliance, not dependency.

What do you think about fitness magazines? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Thomson, C. A., Stopeck, A. T., Bea, J. W., Cussler, E., Nardi, E., Frey, G., & Thompson, P. A. (2010). Changes in body weight and metabolic indexes in overweight breast cancer survivors enrolled in a randomized trial of low-fat vs. reduced carbohydrate diets. Nutrition and Cancer, 62(8), 1142–1152. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2010.513803

- Sacks, F. M., Bray, G. A., Carey, V. J., Smith, S. R., Ryan, D. H., Anton, S. D., McManus, K., Champagne, C. M., Bishop, L. M., Laranjo, N., Leboff, M. S., Rood, J. C., de Jonge, L., Greenway, F. L., Loria, C. M., Obarzanek, E., & Williamson, D. A. (2009). Comparison of Weight-Loss Diets with Different Compositions of Fat, Protein, and Carbohydrates. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(9), 859–873. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa0804748

- Phillips, S. A., Jurva, J. W., Syed, A. Q., Syed, A. Q., Kulinski, J. P., Pleuss, J., Hoffmann, R. G., & Gutterman, D. D. (2008). Benefit of low-fat over low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial health in obesity. Hypertension, 51(2), 376–382. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101824

- Johnston, C. S., Tjonn, S. L., Swan, P. D., White, A., Hutchins, H., & Sears, B. (2006). Ketogenic low-carbohydrate diets have no metabolic advantage over nonketogenic low-carbohydrate diets. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(5), 1055–1061. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1055

- Mettler, S., Mitchell, N., & Tipton, K. D. (2010). Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(2), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b2ef8e

- Layman, D. K., Boileau, R. A., Erickson, D. J., Painter, J. E., Shiue, H., Sather, C., & Christou, D. D. (2003). A reduced ratio of dietary carbohydrate to protein improves body composition and blood lipid profiles during weight loss in adult women. Journal of Nutrition, 133(2), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.2.411

- Churchward-Venne, T. A., Murphy, C. H., Longland, T. M., & Phillips, S. M. (2013). Role of protein and amino acids in promoting lean mass accretion with resistance exercise and attenuating lean mass loss during energy deficit in humans. In Amino Acids (Vol. 45, Issue 2, pp. 231–240). Amino Acids. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-013-1506-0

- Smith, J., & Naughton, L. M. (1993). The effects of intensity of exercise on excess postexercise oxygen consumption and energy expenditure in moderately trained men and women. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 67(5), 420–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00376458

- Stiegler, P., & Cunliffe, A. (2006). The role of diet and exercise for the maintenance of fat-free mass and resting metabolic rate during weight loss. In Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) (Vol. 36, Issue 3, pp. 239–262). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636030-00005

- Mettler, S., Mitchell, N., & Tipton, K. D. (2010). Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(2), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b2ef8e

- Helms, E. R., Zinn, C., Rowlands, D. S., & Brown, S. R. (2014). A systematic review of dietary protein during caloric restriction in resistance trained lean athletes: A case for higher intakes. In International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism (Vol. 24, Issue 2, pp. 127–138). Human Kinetics Publishers Inc. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2013-0054

- Soenen, S., Martens, E. A. P., Hochstenbach-waelen, A., Lemmens, S. G. T., & Westerterp-plantenga, M. S. (2013). Normal protein intake is required for body weight loss and weight maintenance, and elevated protein intake for additional preservation of resting energy expenditure and fat free mass. Journal of Nutrition, 143(5), 591–596. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.112.167593

- Samaha, F. F., Iqbal, N., Seshadri, P., Chicano, K. L., Daily, D. A., McGrory, J., Williams, T., Williams, M., Gracely, E. J., & Stern, L. (2003). A Low-Carbohydrate as Compared with a Low-Fat Diet in Severe Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(21), 2074–2081. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa022637

- Volek, J. S., Sharman, M. J., Gómez, A. L., Judelson, D. A., Rubin, M. R., Watson, G., Sokmen, B., Silvestre, R., French, D. N., & Kraemer, W. J. (2004). Comparison of energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on weight loss and body composition in overweight men and women. Nutrition and Metabolism, 1, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-1-13

- Yancy, W. S., Olsen, M. K., Guyton, J. R., Bakst, R. P., & Westman, E. C. (2004). A Low-Carbohydrate, Ketogenic Diet versus a Low-Fat Diet to Treat Obesity and Hyperlipidemia: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 140(10). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00006

- Howarth, K. R., Phillips, S. M., MacDonald, M. J., Richards, D., Moreau, N. A., & Gibala, M. J. (2010). Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery. Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(2), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00108.2009

- Lane, A. R., Duke, J. W., & Hackney, A. C. (2010). Influence of dietary carbohydrate intake on the free testosterone: Cortisol ratio responses to short-term intensive exercise training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(6), 1125–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1220-5

- Creer, A., Gallagher, P., Slivka, D., Jemiolo, B., Fink, W., & Trappe, S. (2005). Influence of muscle glycogen availability on ERK1/2 and Akt signaling after resistance exercise in human skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology, 99(3), 950–956. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00110.2005

- Denne, S. C., Liechty, E. A., Liu, Y. M., Brechtel, G., & Baron, A. D. (1991). Proteolysis in skeletal muscle and whole body in response to euglycemic hyperinsulinemia in normal adults. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 261(6 24-6). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.6.e809

- Gelfand, R. A., & Barrett, E. J. (1987). Effect of physiologic hyperinsulinemia on skeletal muscle protein synthesis and breakdown in man. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 80(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI113033

- Fryburg, D. A., Jahn, L. A., Hill, S. A., Oliveras, D. M., & Barrett, E. J. (1995). Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I enhance human skeletal muscle protein anabolism during hyperaminoacidemia by different mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 96(4), 1722–1729. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI118217

- Holt, S. H. A., Brand Miller, J. C., & Petocz, P. (1997). An insulin index of foods: The insulin demand generated by 1000-kJ portions of common foods. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(5), 1264–1276. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1264

- Salehi, A., Gunnerud, U., Muhammed, S. J., Stman, E., Holst, J. J., Björck, I., & Rorsman, P. (2012). The insulinogenic effect of whey protein is partially mediated by a direct effect of amino acids and GIP on β-cells. Nutrition and Metabolism, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-48

- Pal, S., & Ellis, V. (2010). The acute effects of four protein meals on insulin, glucose, appetite and energy intake in lean men. British Journal of Nutrition, 104(8), 1241–1248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510001911

- Tipton, K. D., & Wolfe, R. R. (2001). Exercise, protein metabolism, and muscle growth. International Journal of Sport Nutrition, 11(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.11.1.109

- Cooper, G. M. (2000). Protein Degradation. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9957/

- Jaspers, S. R., Fagan, J. M., Satarug, S., Cook, P. H., & Tischler, M. E. (1988). Effects of immobilization on rat hind limb muscles under non‐weight‐bearing conditions. Muscle & Nerve, 11(5), 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.880110508

- Howarth, K. R., Phillips, S. M., MacDonald, M. J., Richards, D., Moreau, N. A., & Gibala, M. J. (2010). Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery. Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(2), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00108.2009

- Miller, S. L., & Wolfe, R. R. (1999). Physical exercise as a modulator of adaptation to low and high carbohydrate and low and high fat intakes. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53, s112–s119. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600751

- Walker, J. L., Heigenhauser, G. J. F., Hultman, E., & Spriet, L. L. (2000). Dietary carbohydrate, muscle glycogen content, and endurance performance in well-trained women. Journal of Applied Physiology, 88(6), 2151–2158. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2151

- Robergs, R. A., Pearson, D. R., Costill, D. L., Fink, W. J., Pascoe, D. D., Benedict, M. A., Lambert, C. P., & Zachweija, J. J. (1991). Muscle glycogenolysis during differing intensities of weight-resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 70(4), 1700–1706. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1700

- Hand, G. A., Shook, R. P., Paluch, A. E., Baruth, M., Crowley, E. P., Jaggers, J. R., Prasad, V. K., Hurley, T. G., Hebert, J. R., O’Connor, D. P., Archer, E., Burgess, S., & Blair, S. N. (2013). The energy balance study: The design and baseline results for a longitudinal study of energy balance. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 84(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2013.816224

- Wang, X., Ouyang, Y., Liu, J., Zhu, M., Zhao, G., Bao, W., & Hu, F. B. (2014). Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ (Online), 349. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490

- Geliebter, A., Maher, M. M., Gerace, L., Gutin, B., Heymsfield, S. B., & Hashim, S. A. (1997). Effects of strength or aerobic training on body composition, resting metabolic rate, and peak oxygen consumption in obese dieting subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(3), 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/66.3.557

- Sigal, R. J., Kenny, G. P., Boulé, N. G., Wells, G. A., Prud’homme, D., Fortier, M., Reid, R. D., Tulloch, H., Coyle, D., Phillips, P., Jennings, A., & Jaffey, J. (2007). Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(6), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00005

- Willis, L. H., Slentz, C. A., Bateman, L. A., Shields, A. T., Piner, L. W., Bales, C. W., Houmard, J. A., & Kraus, W. E. (2012). Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults. Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(12), 1831–1837. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01370.2011

- Thomas, D. M., Bouchard, C., Church, T., Slentz, C., Kraus, W. E., Redman, L. M., Martin, C. K., Silva, A. M., Vossen, M., Westerterp, K., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2012). Why do individuals not lose more weight from an exercise intervention at a defined dose? an energy balance analysis. Obesity Reviews, 13(10), 835–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01012.x

- Rustaden, A. M., Gjestvang, C., Bø, K., Haakstad, L. A. H., & Paulsen, G. (2020). Similar Energy Expenditure During BodyPump and Heavy Load Resistance Exercise in Overweight Women. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 570. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00570

- Melanson, E. L., Keadle, S. K., Donnelly, J. E., Braun, B., & King, N. A. (2013). Resistance to exercise-induced weight loss: Compensatory behavioral adaptations. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 45(8), 1600–1609. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828ba942

- Sawyer, B. J., Bhammar, D. M., Angadi, S. S., Ryan, D. M., Ryder, J. R., Sussman, E. J., Bertmann, F. M. W., & Gaesser, G. A. (2015). Predictors of fat mass changes in response to aerobic exercise training in women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(2), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000726

- Alen, M., & Hakkinen, K. (1985). Physical health and fitness of an elite bodybuilder during 1 year of self-administration of testosterone and anabolic steroids: A case study. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1025808

- Hartgens, F., & Kuipers, H. (2004). Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids in athletes. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 34, Issue 8, pp. 513–554). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200434080-00003