“Can you recommend a book for…?”

“What are you reading right now?”

“What are your favorite books?”

I get asked those types of questions a lot and, as an avid reader and all-around bibliophile, I’m always happy to oblige.

I also like to encourage people to read as much as possible because knowledge benefits you much like compound interest. The more you learn, the more you know; the more you know, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more opportunities you have to succeed.

On the flip side, I also believe there’s little hope for people who aren’t perpetual learners. Life is overwhelmingly complex and chaotic, and it slowly suffocates and devours the lazy and ignorant.

So, if you’re a bookworm on the lookout for good reads, or if you’d like to get into the habit of reading, this book club for you.

The idea here is simple: Every month, I’ll share a book that I’ve particularly liked, why I liked it, and several of my key takeaways from it along with my thoughts on each.

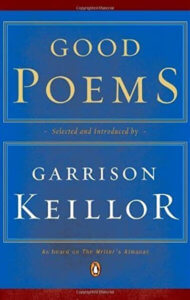

Okay, let’s get to this installment’s featured book: Good Poems by Garrison Keillor.

I haven’t read much poetry since high school and didn’t particularly dig on it then, but as a professional (“professional”) scribbler, I’ve come to appreciate verse, and I believe reading and copybooking it has helped me improve my writing and creative thinking.

Specifically . . .

- Poetry can be aesthetically pleasing regardless of the message through its many potential patterns of rhythm and sound. To get an idea of how intricate and diverse these systems are, check out the book The Book of Forms by Lewis Putnam Turco. Skill in the use of such forms can greatly enhance the appeal of any writing, because they work at a subconscious level—words are just more interesting when they’re structured in certain ways.

- Poetry often involves describing a compelling story or idea in very few words, which is the essence of good writing. At least half of effective editing is trimming and clarifying, and this is doubly so with poetry, where every word must be weighed and all excesses and impurities must be eliminated. If you scrutinize your own writing in the same way, your drafts will improve.

- Poetry is pure pathos (an appeal to emotion), which I believe is the toughest to learn but also most powerful of the three pillars of classical rhetoric (with the other two being ethos—authority or credibility—and logos—facts and logic). The better I can stir my reader’s emotions, the more effective my communication will be, and poetry hones this skill.

- Poetry can be challenging to read, almost like puzzle-solving, which sharpens your mind. It also exercises your ability to think laterally, which is a crucial element of the creative process. I believe everybody has a creative streak in them, and tapping it into is merely a matter of practice—if you act like an “idea person,” you’ll become one, and poetry inspires me to ideate.

- Poetry is a treasure trove of exotic and stimulating figures of speech, which can add brilliant colors to otherwise monochromatic prose (see what I did there?). Well-turned metaphors, similes, and analogies are particularly powerful in this regard, and poetry is rich with them.

All that is why I include poetry in the simple system I use for finding, choosing, reading, and remembering books.

And as for the book I’m reviewing here, Good Poems by Garrison Keillor, it contains a collection of his favorite poems from the past and present from a multitude of poets. I enjoyed it because there’s something here for everyone, including greenhorns like me.

Usually, book club articles contain my key takeaways from a book as well as my thoughts on them, but in this case, I’ll just share several of my favorite poems from Good Poems and let you come to your own conclusions about them.

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

My 7 Key Takeaways from Good Poems

1

Excelsior

By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The shades of night were falling fast,

As through an Alpine village passed

A youth, who bore, ‘mid snow and ice,

A banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

His brow was sad; his eye beneath,

Flashed like a falchion from its sheath,

And like a silver clarion rung

The accents of that unknown tongue,

Excelsior!

In happy homes he saw the light

Of household fires gleam warm and bright;

Above, the spectral glaciers shone,

And from his lips escaped a groan,

Excelsior!

“Try not the Pass!” the old man said;

“Dark lowers the tempest overhead,

The roaring torrent is deep and wide!”

And loud that clarion voice replied,

Excelsior!

“Oh stay,” the maiden said, “and rest

Thy weary head upon this breast!”

A tear stood in his bright blue eye,

But still he answered, with a sigh,

Excelsior!

“Beware the pine-tree’s withered branch!

Beware the awful avalanche!”

This was the peasant’s last Good-night,

A voice replied, far up the height,

Excelsior!

At break of day, as heavenward

The pious monks of Saint Bernard

Uttered the oft-repeated prayer,

A voice cried through the startled air,

Excelsior!

A traveller, by the faithful hound,

Half-buried in the snow was found,

Still grasping in his hand of ice

That banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

There in the twilight cold and gray,

Lifeless, but beautiful, he lay,

And from the sky, serene and far,

A voice fell like a falling star,

Excelsior!

2

Otherwise

By Jane Kenyon

I got out of bed

on two strong legs.

It might have been

otherwise. I ate

cereal, sweet

milk, ripe, flawless

peach. It might

have been otherwise.

I took the dog uphill

to the birch wood.

All morning I did

the work I love.

At noon I lay down

with my mate. It might

have been otherwise.

We ate dinner together

at a table with silver

candlesticks. It might

have been otherwise.

I slept in a bed

in a room with paintings

on the walls, and

planned another day

just like this day.

But one day, I know,

it will be otherwise.

3

Song of Myself, Section 20

By Walt Whitman

I know I am deathless,

I know this orbit of mine cannot be swept by the carpenter’s compass,

I know I shall not pass like a child’s carlacue cut with a burnt stick at night.

I know I am august,

I do not trouble my spirit to vindicate itself or be understood,

I see that the elementary laws never apologize,

I reckon I behave no prouder than the level I plant my house by, after all.

I exist as I am—that is enough,

If no other in the world be aware, I sit content,

And if each and all be aware, I sit content.

One world is aware and by far the largest to me, and that is myself,

And whether I come to my own to-day or in ten thousand or ten million years,

I can cheerfully take it now, or with equal cheerfulness I can wait.

4

Egg

by C.G. Hanzlicek

I’m scrambling an egg for my daughter.

“Why are you always whistling?” she asks.

“Because I’m happy.”

And it’s true,

Though it stuns me to say it aloud;

There was a time when I wouldn’t

Have seen it as my future.

It’s partly a matter

Of who is there to eat the egg:

The self fallen out of love with itself

Through the tedium of familiarity,

Or this little self,

So curious, so hungry,

Who emerged from the woman I love,

A woman who loves me in a way

I’ve come to think I deserve,

Now that it arrives from outside me.

Everything changes, we’re told,

And now the changes are everywhere:

The house with its morning light

That fills me like a revelation,

The yard with its trees

That cast a bit more shade each summer,

The love of a woman

That both is and isn’t confounding,

And the love

Of this clamor of questions at my waist.

Clamor of questions,

You clamor of answers,

Here’s your egg.

5

Leisure

By William Henry Davies

What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

No time to stand beneath the boughs

And stare as long as sheep or cows.

No time to see, when woods we pass,

Where squirrels hide their nuts in grass.

No time to see, in broad daylight,

Streams full of stars, like skies at night.

No time to turn at Beauty’s glance,

And watch her feet, how they can dance.

No time to wait till her mouth can

Enrich that smile her eyes began.

A poor life this is if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.

6

In a Prominent Bar in Secaucus One Day

By X.J. Kennedy

In a prominent bar in Secaucus one day

Rose a lady in skunk with a topheavy sway,

Raised a knobby red finger–all turned from their beer–

While with eyes bright as snowcrust she sang high and clear:

‘Now who of you’d think from an eyeload of me

That I once was a lady as proud as could be?

Oh I’d never sit down by a tumbledown drunk

If it wasn’t, my dears, for the high cost of junk.

‘All the gents used to swear that the white of my calf

Beat the down of the swan by a length and a half.

In the kerchief of linen I caught to my nose

Ah, there never fell snot, but a little gold rose.

‘I had seven gold teeth and a toothpick of gold,

My Virginia cheroot was a leaf of it rolled

And I’d light it each time with a thousand in cash–

Why the bums used to fight if I flicked them an ash.

‘Once the toast of the Biltmore, the belle of the Taft,

I would drink bottle beer at the Drake, never draught,

And dine at the Astor on Salisbury steak

With a clean tablecloth for each bite I did take.

‘In a car like the Roxy I’d roll to the track,

A steel-guitar trio, a bar in the back,

And the wheels made no noise, they turned ever so fast,

Still it took you ten minutes to see me go past.

‘When the horses bowed down to me that I might choose,

I bet on them all, for I hated to lose.

Now I’m saddled each night for my butter and eggs

And the broken threads race down the backs of my legs.

‘Let you hold in mind, girls, that your beauty must pass

Like a lovely white clover that rusts with its grass.

Keep your bottoms off barstools and marry you young

Or be left–an old barrel with many a bung.

‘For when time takes you out for a spin in his car

You’ll be hard-pressed to stop him from going too far

And be left by the roadside, for all your good deeds,

Two toadstools for tits and a face full of weeds.’

All the house raised a cheer, but the man at the bar

Made a phone call and up pulled a red patrol car

And she blew us a kiss as they copped her away

From that prominent bar in Secaucus, N.J.

7

Birthday Card to My Mother

By Philip Appleman

The toughness indoor people have:

the will

to brave confusion in

mohair sofas, crocheted doilies – challenging

in every tidy corner some

bit of the outdoor drift and sag;

the tenacity

in forty quarts of cherries up for winter,

gallon churns of sherbet at

family reunions,

fifty thousand suppers cleared away;

the tempering

of rent-men at the front door, hanging on,

light bills overdue,

sons off to war or buried, daughters

taking on the names of strangers.

You have come through

the years of wheelchairs, loneliness –

a generation of pain

knotting the joints like ancient apple trees;

you always knew this was no world to be weak in:

where best friends wither to old

phone numbers in far-off towns;

where the sting of children is always

sharper than serpents’ teeth; where

love itself goes shifting

and slipping away to shadows.

You have survived it all,

come through wreckage and triumph hard

at the center but spreading

gentleness around you – nowhere

by your bright hearth has the dust

of bitterness lain unswept;

today, thinking back, thinking ahead

to other birthdays, I

lean upon your courage

and sign this card, as always,

with love.