“Hip dips” are one of the most talked-about body image topics online.

Despite being a normal part of human anatomy, they’re often framed as a flaw—leading many people to search for ways to get rid of them.

That’s sparked a lot of conflicting advice. Some health and fitness “gurus” claim you can erase hip dips with specially designed workouts. Others say hip dips are determined by bone structure, which means lifestyle changes won’t help at all.

But what’s actually true?

In this article, you’ll learn what hips are, what causes them, and whether it’s possible to change how they look with diet and exercise.

Key Takeaways

- Hip dips are normal. They’re a common feature of anatomy, not a medical problem or a sign you’re out of shape.

- Bone structure is the main reason hip dips exist. The shape of your hips and thigh bones matters more than any exercise or diet trick.

- You can’t completely get rid of hip dips with workouts. You can’t change your bones, no matter how you train.

- Building glute muscle may make hip dips less noticeable. More muscle can change how the area looks, even if the dip doesn’t disappear.

- You don’t need to “fix” hip dips to have a healthy or attractive body. They’re just one of many normal body variations.

Table of Contents

+

What Are Hip Dips (Violin Hips)?

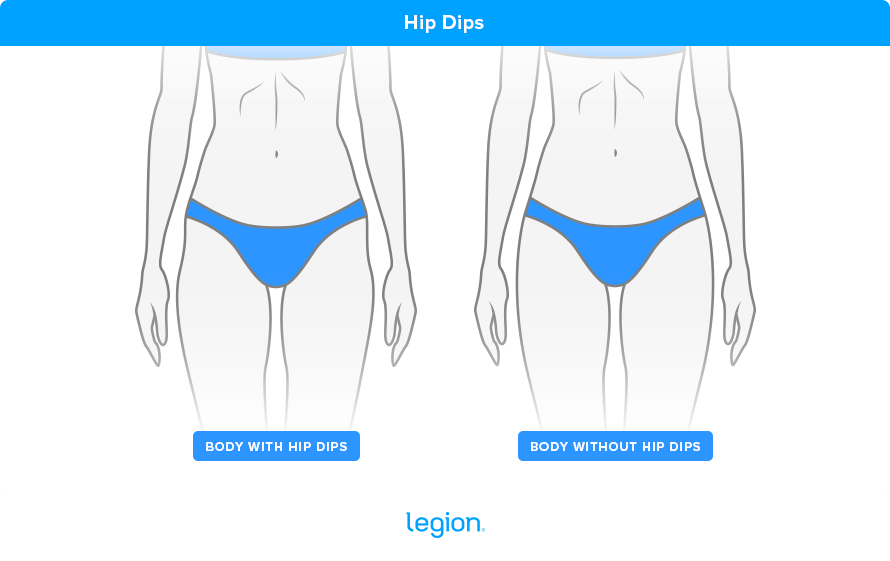

Hip dips (sometimes called “violin hips”) are the natural inward curves on the sides of your hips—right below your hip bones and above the top of your thighs. Here’s how they look:

They aren’t a medical problem. They aren’t a sign you’re “out of shape.” And they aren’t something you “caused” by training wrong.

They’re just a normal part of how your pelvis and upper thigh area are shaped—and how your muscle and body fat sit on top of that structure.

What Causes Hip Dips?

Here’s the simplest way to think about what causes hip dips: your skeleton sets the outline of your hips, and everything else fills it in.

That’s why hip dips are mostly about anatomy—not “toning,” not a lack of some magic exercise, and not a sign you need to “fix” anything.

Bone Structure vs. Fat Distribution and Muscle Mass

Bone structure is the main reason hip dips exist and why they vary person to person.

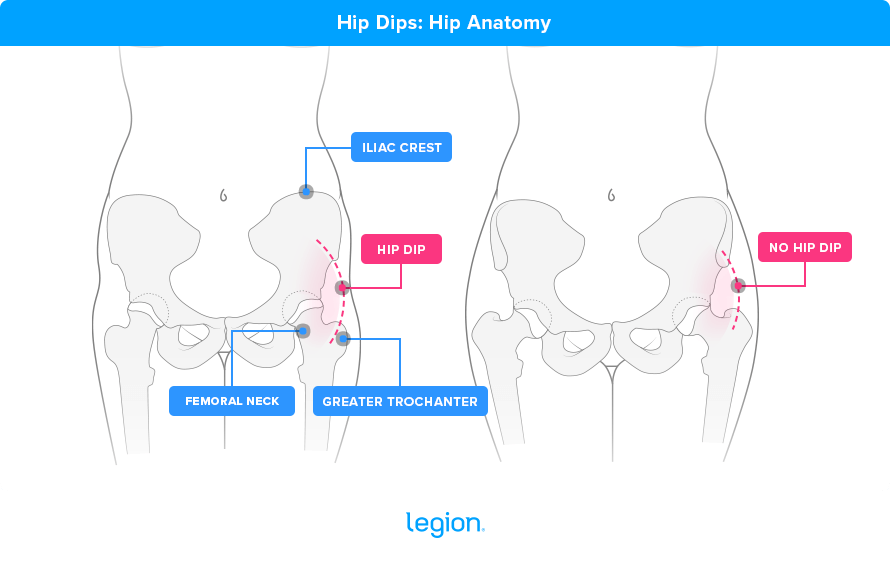

In particular, the relationship between the top of your thigh bone and your hip bone affects how smooth—or how “dipped”—the outer hip line looks.

If there’s a big space between your thigh bone and hip bone and you have a longer femoral neck that connects almost vertically, you’re more likely to have noticeable hip dips. If the space is smaller and the femoral neck bone is shorter and connects almost horizontally, hip dips are less likely to be noticeable.

Here’s a picture to show what that looks like:

Then you have the secondary factors: fat distribution and muscle mass.

These can change how visible hip dips look because:

- If you carry less body fat around your hips and glutes, the dip may look sharper.

- If your glute muscles (especially the outer or upper glutes) are underdeveloped, the dip may stand out more.

- If you build more glute muscle, you may visually “fill in” some of that curve.

The key point is this:

You may be able to influence the appearance of your hips to a small degree, but you can’t rewrite the basic shape your bones create.

Are Hip Dips Normal—and Does Everyone Have Them?

Yes—hip dips are normal.

And in a broad sense, everyone has some version of them, because that inward curve is part of how the pelvis and thigh meet and how soft tissue sits on top of that structure.

What changes from person to person is how noticeable the dips are.

That depends mostly on your bone structure, and then (to a lesser degree) how much muscle and body fat you carry around your hips and glutes.

So if you’re thinking, “Why do I have hip dips?” the answer is usually very unexciting: because that’s how your hips are built.

Can You Get Rid of Hip Dips?

That depends on what you mean by “get rid of hip dips.” If you mean erase them completely with exercise, the honest answer is no. You can’t train your bones into a different shape.

But if you mean make them less noticeable—or improve your overall hip and glute shape so they bother you less—then yes, a lot of people can change how hip dips look.

What Can Change Their Appearance vs. What Can’t

What you can’t change:

- The shape of your pelvis

- The placement of key bone landmarks

- The basic structure that creates the inward curve

What you often can change:

- How much glute muscle you carry

- Your overall body composition

- How “sharp” the dip looks compared to the rest of your hips and glutes

This matters because most hip dip advice fails in one of two ways:

- It promises a complete fix that isn’t possible without cosmetic procedures.

- It swings too far the other way and says “nothing works,” which isn’t true if your goal is improving appearance—not changing your skeleton.

The Best Exercises for Minimizing Hip Dips

There’s no such thing as a magical “hip dip exercise” that targets the dip itself. What you can do, though, is build your glutes so you have more muscle where it matters visually.

Squat

Why: Highly effective for developing hip strength and stability, especially when you squat to parallel or deeper.

How to:

- Set a barbell in a rack at about chest height.

- Step under it, pinch your shoulder blades together, and rest the bar across your upper back.

- Lift the bar out, step back, and set your feet slightly wider than shoulder-width with your toes turned out.

- Keeping your back straight, sit down and push your knees out in the same direction as your toes.

- Reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

READ MORE: How to Do the Back Squat: Form, Benefits, and More

Deadlift

Why: Lets you train the glutes and hamstrings with heavy weights, which is great for overall lower-body muscle and shape.

How to:

- Stand with your feet slightly narrower than shoulder width, toes pointed slightly out.

- Position the bar over your midfoot, about an inch from your shins.

- Push your hips back and grip the bar just outside your legs.

- Take a deep breath, brace your core, and flatten your back.

- Drive through your heels to stand upright, keeping the bar close to your body.

- Reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

READ MORE: How to Deadlift with Proper Technique

Single-Leg Hip Thrust

Why: Trains the glutes hard one side at a time, which is useful for building shape and fixing side-to-side imbalances.

How to:

- Sit on the ground with your shoulders resting against a bench perpendicular to your body.

- Place a dumbbell in your hip crease.

- Plant your feet on the floor about shoulder-width apart and 12–18 inches from your butt.

- Straighten your left knee to lift your left foot off the floor.

- Push the dumbbell upward by pressing through your right heel until your upper body and right thigh is parallel to the ground and your right shin is vertical.

- Reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

- Once you’ve completed the desired number of reps, repeat the process on your left side.

Single-Leg Romanian Deadlift

Why: Establishes a strong “mind-muscle connection” with your glutes by focusing on one side of your body at a time, which may enhance muscle growth in some scenarios.

How to:

- Stand tall holding a dumbbell in your right hand.

- Flatten your back and lower the weight toward the floor in a straight line while keeping your right leg mostly straight, allowing your butt to move backward and your left leg to straighten behind you as you descend.

- Once you feel a stretch in your hamstring, reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

- Once you’ve completed the desired number of reps, repeat the process on your left side.

Step-up

Why: Outstanding glute exercise that’s easier on your knees and back than other lower-body exercises.

How to:

- Holding a dumbbell in each hand, place your right foot on a box, bench, or other surface about knee height off the floor.

- Keeping your weight on your right foot, fully straighten your right leg.

- Lower your left leg toward the floor and return to starting position.

READ MORE: Weighted Step-Ups Guide: How to Do Dumbbell Step-Ups

Curtsy Lunge

Why: Trains your glutes through a unique range of motion, which may benefit growth.

How to:

- Holding a dumbbell in each hand, stand with your feet about hip-width apart.

- Step diagonally backward with your left leg so that it crosses your right leg.

- With most of the weight on the right leg, lower your body by bending both knees at the same time until the left knee touches the floor.

- Reverse the movement and return to standing position.

- Once you’ve completed the desired number of reps, repeat the process on your left side.

Glute Bridge

Why: A simple, beginner-friendly way to isolate and strengthen the glutes using bodyweight or light load.

How to:

- Lie on your back on the floor, keeping your arms by your sides and palms touching the floor.

- With knees bent, place your feet 15–18 inches apart and 6–2 inches from your butt, pointing your toes slightly outward.

- Lift your butt off the floor by pressing your shoulders and heels into the floor, pushing your knees out in the same direction as your toes, and squeezing your glutes.

- Continue thrusting your hips upward until your butt, hips, and knees form a straight line and your shins are vertical.

- Reverse the movement and return to the starting position.

READ MORE: How to Do the Glute Bridge: Form, Benefits, and Variations

Cable Side Leg Raise

Why: Trains the outer hip and upper glute—muscles that can help “fill out” the hip area visually.

How to Do the Cable Side Leg Raise:

- Set the pulley on a cable machine to the lowest setting and connect the cuff attachment.

- Stand with one shoulder next to the cable machine, keeping your feet shoulder-width apart.

- Secure the cuff around your outer ankle.

- Place your outside hand on your hip and the other hand on the cable machine.

- Raise the outer leg to your side as far as possible

- Reverse the movement and return to standing position.

A Simple Hip Dip Workout for Strong, Sculpted Hip Muscles

Since hip dips are a natural and harmless part of anatomy, there’s no reason to do workouts designed to “fix” them. That said, if your hips dips are a hangup you’d prefer to minimize, building glute muscle may help a little.

More importantly, it also boosts your physical performance in just about every way, including helping you lift heavier weights, run faster, jump higher, and stay injury-free.

For best results, replace a leg workout in your strength training plan with this hip dip workout:

- Squat: 3 sets | 8–10 reps | 3–5 min rest

- Single-Leg Romanian Deadlift: 3 sets | 8–10 reps | 3–5 min rest

- Step-up: 3 sets | 8–10 reps | 2–3 min rest

- Cable Side Leg Raise: 3 sets | 8–10 reps | 2–3 min rest

Other Ways to Improve the Appearance of Hip Dips

If you want to make hip dips less noticeable, lifting is usually the best starting point—but it isn’t the only lever you can pull.

Body Composition

Hip dips can look different at different body-fat levels because fat isn’t stored evenly across the hips, waist, and thighs.

If you tend to hold more fat in areas like your lower abs, love handles, or upper thighs, a higher body-fat level can sometimes make the inward curve at the hips stand out more. In those cases, losing some fat may make the transition from waist to hips to thighs look smoother.

For other people, getting leaner has the opposite effect. With less soft tissue around the hips, the dip can become more noticeable.

That’s why fat loss alone isn’t a reliable fix. The most consistent approach is usually to build muscle first—especially in the glutes—then decide whether you want to lose fat, maintain, or slowly gain based on your overall physique goals.

Cosmetic Options

Some people choose cosmetic procedures to change hip contour—most often fillers or fat-transfer approaches.

That’s a personal choice, and it’s outside the scope of training and nutrition.

Just understand the tradeoffs: cost, maintenance, risk, and unpredictable outcomes. And don’t let anyone convince you that you need a procedure to have an attractive body.

The Bottom Line On Getting Rid of Hip Dips

Hip dips are normal. They’re mostly a product of bone structure, which means you can’t “delete” them with a special workout.

But you can influence how they look by building your glutes, improving body composition, and focusing on changes that are actually within your control.

And if you decide you don’t want to change them at all?

Great.

You’re not “settling.” You’re recognizing that a normal body feature doesn’t need fixing.

FAQ #1: What are hip dips caused by?

Hip dips are mostly caused by bone structure—specifically how your pelvis and thigh bone are shaped and how they meet. If there’s more space between the top of your thigh bone (greater trochanter) and the top of your hip bone (iliac crest), hip dips tend to look more noticeable.

Muscle and fat distribution can also affect how visible they look. If you have less muscle and less fat around your hips and glutes, the dip may look deeper. Building glute muscle can make it look less pronounced.

FAQ #2: Are hip dips considered attractive?

Attractiveness is subjective. Hip dips are a normal body feature largely shaped by genetics and anatomy, and plenty of people find bodies with hip dips attractive.

FAQ #3: Is it actually possible to fix hip dips?

You can’t change the bone structure that creates hip dips, so you can’t completely eliminate them with diet or exercise. But many people can make them less noticeable by building glute muscle and improving overall body composition.

FAQ #4: Why do I have hip dips?

Because of your anatomy and genetics. Hip dips are a common feature created by the shape of your pelvis and thigh bones and how muscle and fat are distributed around them.

Want More Content Like This?

Check out these articles:

- How to Fix “Mom Butt” After Pregnancy

- How to Get Rid of Bat Wings: Exercise & Diet That Works

- Transform Your Pear-Shaped Body: Exercises & Diet Tips

- 13 Best Exercises to Lift Your Breasts Naturally

Scientific References +

- Barbalho, Matheus, et al. “Back Squat vs. Hip Thrust Resistance-Training Programs in Well-Trained Women.” International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 41, no. 5, 23 Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1082-1126.

- Caterisano, Anthony, et al. “The Effect of Back Squat Depth on the EMG Activity of 4 Superficial Hip and Thigh Muscles.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 16, no. 3, 1 Aug. 2002, pp. 428–432, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12173958/.

- Simenz, Christopher J., et al. “Electromyographical Analysis of Lower Extremity Muscle Activation during Variations of the Loaded Step-up Exercise.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 12, Dec. 2012, pp. 3398–3405, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3182472fad.

- Morin, Jean-Benoît, et al. “Sprint Acceleration Mechanics: The Major Role of Hamstrings in Horizontal Force Production.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 6, no. 404, 24 Dec. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4689850/, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00404.

- Millar, Nicole A, et al. “In-Season Hip Thrust vs. Back Squat Training in Female High School Soccer Players.” International Journal of Exercise Science, vol. 13, no. 4, 2020, pp. 49–61, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7039497/#b34-ijes-13-4-49. Accessed 5 Mar. 2024.

- Buckthorpe, Matthew, et al. “ASSESSING and TREATING GLUTEUS MAXIMUS WEAKNESS – a CLINICAL COMMENTARY.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 14, no. 4, July 2019, p. 655, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6670060/.