When it comes to building muscle and losing fat, most people “in the know” agree on at least a few things:

- A high-protein diet is best.

- An energy surplus is necessary for maximizing muscle growth.

- An energy deficit is necessary for losing fat.

In fact, those fundamentals are so well established both scientifically and anecdotally that they form a litmus test of sorts for diet “gurus” and methodologies

If someone claims otherwise–that a low-protein diet is optimal or that you don’t have to worry about calories if you “eat clean,” for example–you should ignore everything they say.

That may sound harsh but, as you probably know by now, one of the biggest barriers to getting fit is just figuring out who to listen to.

Just because someone sounds smart doesn’t mean they know what he’s talking about. A degree doesn’t mean she can get results. A great body doesn’t mean he also has a reliable, universally workable system for getting there.

Determining who is and isn’t full of shit can be tricky, but know this:

One of the easiest ways to quickly assess the reliability of a self-style fitness expert is their grasp of the the non-negotiable fundamentals of dieting.

If someone…

- rejects the laws of energy balance…

- claims certain foods make you fat by “clogging your hormones”…

- rants about how sugar is ruining your life…

- pushes other foods as the “keys to weight loss”…

- or otherwise claims how a century of metabolic research has it all wrong and he knows better…

…he should be defrocked, pilloried, and exiled. He’s a fitness Flat Earther.

I don’t care if these misguided people have good intentions, either. If they’re going to step up on the stump and gather a crowd, they now have a responsibility to be well informed. We all have a right to ignorance but not to infect others.

As the saying goes, hell is full of good intentions but heaven is full of good works.

And no, I don’t presume to know everything or consider myself a Grand Inquisitor of health and fitness advice. I do, however, get a lot more right than wrong and have hundreds of success stories to prove it. I can rest easy at night knowing I’m helping people reach their fitness goals in a reasonable amount of time while actually enjoying the process.

So, all that brings me back to the topic of this article, carbohydrate intake.

Ask Google how many carbs you should eat, weed out the idiots, and you’re left with a lot of contradictory answers.

Many well-respected health and fitness authorities argue why low-carb dieting is the way of the future. Many others rail against it as just another fad. Many still are in the middle saying “it depends…”

Well, in this article, I’m going to explain the science and logic behind my position, which is this:

If you’re healthy and physically active, and especially if you lift weights regularly, you’re probably going to do best with more carbohydrate, not less.

And yes, that applies to both building muscle and losing fat. The reality is a relatively high carbohydrate intake can help you do both, and this article will explain why.

Table of Contents

+

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

The Great Carbohydrate Controversy

It’s easier to talk with some people about religion and politics than diet. And if you’re going to get into a diet debate, it’ll probably get hot over the subjects of carbs.

Why? What is so contentious about this little bugger?

Well, most of the criticism of the carbohydrate revolves around the hormone insulin and its effects in the body.

Every time we eat carbs our insulin levels spike, which, we’re told, tells our body to store everything we eat as fat. Thus, if we want to lose fat or prevent weight gain, eating as little carbohydrate and keeping insulin levels as low as possible is the key.

It’s easy to sell simple explanations like this to the unsuspecting masses, but the reality is far more nuanced.

Yes, insulin triggers fat storage, but no, it doesn’t make you fat.

I know that sounds like dietary doublespeak but I’ll explain.

Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas and its job is vitally important. When you eat food, the nutrients it contains make their way into your bloodstream along with insulin. Insulin tells cells to “open up” to receive the nutrients and thus causes them to be absorbed into muscle and fat tissues.

As your body absorbs more and more of the food you ate, insulin levels drop. When everything is cleared from the blood, insulin levels settle at a low, “baseline” level. (This is known as the “fasted” state.)

When you eat again, the process repeats. This is how your body stays alive.

Now, when viewed that way, insulin seems like an alright dude. We literally can’t live without it so how bad can it really be?

Well, if you’ve been paying attention, you noticed that earlier I said that insulin causes both muscle and fat tissues to “open up” to the foods you eat. It’s that latter role, related to fat storage, that has so many people in a tizzy.

You see, insulin tells the body it can stop burning its fat stores for energy and use the food you just ate instead. It also tells your fat cells to store a bit of the food energy for use when it runs out.

This physiological mechanism makes for reductionist dieting advice that goes something like this:

High daily carb intake = high insulin levels = store a bunch of fat = be fat.

And then the corollary:

Low daily carb intake = low insulin levels = burn a bunch of fat = be lean.

Simple is sexy and it’s hard to get simpler than that. Too bad it’s bullshit.

Insulin doesn’t make you fat. Overeating does.

Yes, insulin helps your body increase its fat stores, but fat storage isn’t bad per se. If your body weren’t able to replenish fat stores it would have no energy reserve to tap into when food isn’t available and you would simply die.

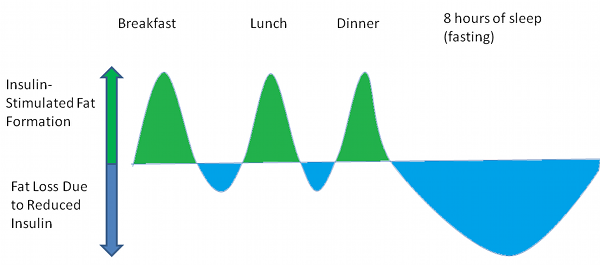

Check out the following graph:

This is how your body fat stores increase and decrease each and every day.

The green portions represent periods of fat storage following meals (energy surplus). The blue portions represent periods of fat burning following the absorption of meals (energy deficit). And as you can see, insulin is merely the messenger, not the underlying mechanism.

Let’s now look at how that plays out over time.

When people say they don’t want to gain fat, what they’re really saying is they don’t want their total fat mass to increase over time. That is, if you have 25 pounds of fat on your body now, you don’t want to have 35 pounds a year now from now.

Now, a rise in total fat mass represents a rise in the amount of energy stored in your body. The first law of thermodynamics states that energy can change forms but can’t be created or destroyed, so what has to happen for your body to increase is energy stores?

It must obtain more energy than it burns so it can use the surplus for fat storage. And insulin can’t spontaneously create additional energy for fat storage–it can only work with what you give it.

That’s why research has shown that so long as they’re eating less energy than they’re burning, people lose fat equally well on high-carbohydrate or low-carbohydrate diets.

That’s why professor Mark Haub was able to lose 27 pounds on a “convenience store diet” consisting mainly of Twinkies, Little Debbie cakes, Doritos, and Oreos: he simply fed his body less energy than it was burning.

The bottom line is insulin levels and the amount of carbs you eat have little to do with losing or gaining weight. Energy balance is the key.

How Many Carbs Should You Be Eating Then?

Now that you’ve learned why you have no reason to fear carbs, let’s talk about how many you should be eating.

As I mentioned earlier in this article, if you’re physically active, and especially if you lift weights regularly, you’re almost guaranteed to do better on a higher-carb diet than a low-carb one.

That said, if you’re sedentary and overweight, you’re guaranteed to do better on a low-carb diet simply because your body doesn’t need the energy they provide.

Chances are you’re in the former category and not the latter, so let’s talk more about determining carbohydrate intake for active people.

How Many Carbs to Eat for Building Muscle

One of the substances your body breaks carbs you eat down into is glycogen. This is a form of potential energy that is stored primarily in the liver and muscles.

Glycogen is a primary energy source for intense exercise, which is why keeping your liver and muscles full of it can dramatically improve workout performance.

Maintaining high levels of glycogen requires maintaining relatively high levels of carbohydrate intake.

The elevations in insulin levels helps you build more muscle too.

Insulin isn’t anabolic like other hormones such as testosterone, but it does have powerful anti-catabolic properties. This means that insulin decreases the rate at which muscle proteins are broken down, which creates a more anabolic environment conducive to muscle growth.

This isn’t just theory, either. There are several studies that found that high-carbohydrate diets are superior to low-carbohydrate ones for building both muscle and strength.

One of these studies was conducted by scientists at Ball State University. Researchers found that low muscle glycogen levels (which is inevitable with low-carbohydrate dieting) impair post-workout cell signaling related to muscle growth.

Another study conducted by researchers at the University of North Carolina found that when athletes followed a low-carbohydrate diet, resting cortisol levels increased and free testosterone levels decreased. This is more or less the exact opposite of what athletes want for optimizing performance and body composition.

These studies help explain the findings of other research on low-carbohydrate dieting.

For example, a study conducted by researchers at the University of Rhode Island looked at how low- and high-carbohydrate intakes affected exercise-induced muscle damage, strength recovery, and whole body protein metabolism after a strenuous workout.

The result was the subjects on the low-carbohydrate diet (which wasn’t all that low, actually—about 226 grams per day, versus 353 grams per day for the high-carbohydrate group) lost more strength, recovered slower, and showed lower levels of protein synthesis.

In this study, researchers at McMaster University compared high- and low-carbohydrate dieting with subjects performing daily leg workouts. They found that those on the low-carbohydrate diet experienced higher rates of protein breakdown and lower rates of protein synthesis, resulting in less overall muscle growth than their higher-carbohydrate counterparts.

This is why I recommend that when you’re wanting to maximize muscle growth, you set your carbohydrate intake somewhere in the range of 1 to 3 grams per pound of body weight.

Click here to learn more about carb intake and “bulking.”

How Many Carbs to Eat for Losing Fat

Low-carb dieting is has become the go-to solution for weight loss, but there’s little scientific evidence to support this.

There are about 20 studies that low-carb proponents bandy about as definitive proof of the superiority of low-carb dieting for weight loss. This, this, and this are common examples. If you simply read the abstracts of these studies, low-carb dieting definitely seems more effective, and this type of glib “research” is what most low-carbers base their beliefs on.

But there’s a big problem with many of these studies, and it has to do with protein intake. The low-carb diets in these studies invariably contained more protein than the low-fat diets. Yes, one for one…without fail.

What we’re actually looking at in these studies is a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet vs. low-protein, high-fat diet, and the former wins every time. But we can’t ignore the high-protein part and say it’s more effective because of the low-carb element.

In fact, better designed and executed studies prove the opposite: when protein intake is high, low-carb dieting offers no especial weight loss benefits.

As you can tell, I’m no fan of low-carb dieting for weight loss, but I do think it can be useful for people very overweight, whose bodies don’t process carbs well.

Insulin sensitivity refers to how responsive your cells are to insulin’s signals, and insulin response–or insulin secretion–refers to how much insulin is secreted into your blood in response to food eaten.

Research has shown that weight loss efforts aren’t improved or impaired by insulin sensitivity or insulin resistance per se, but there’s evidence that people with poor insulin sensitivity and response may lose more weight on a low-carb diet.

For instance, a study conducted by researchers at the Tufts-New England Medical Center found that a low-glycemic load diet helped overweight adults with high insulin secretion lose more weight, but not overweight adults with low insulin secretion.

A study conducted by scientists at the University of Colorado demonstrated that obese women that were insulin sensitive lost significantly more weight on a high-carb, low-fat diet than a low-carb, high-fat diet (average weight loss of 13.5% vs. 6.8% of body weight, respectively); and those that were insulin resistant lost significantly more weight on a low-carb, high-fat diet than a high-carb, low-fat diet (average weight loss of 13.4% vs. 8.5% of body weight, respectively).

Two studies is hardly definitive, but it’s interesting and worth noting.

Practically speaking, this wouldn’t apply to you unless you’re obese, sedentary, and near diabetic, and don’t want to exercise to lose weight.

So, here’s how I recommend you calculate how many carbs to eat for weight loss:

1. Calculate your calorie target for weight loss.

Click here to learn how to do this.

2. Set your protein intake to 1 to 1.2 grams per pound of body weight.

If you’re very overweight (25%+ body fat for men and 30%+ for women), set it to 1.2 grams per pound of lean mass. (Click here to learn how to calculate this.)

3. Set your fat intake to 0.2 grams per pound of body weight.

If you’re very overweight, set it to 0.4 grams per pound of lean mass.

4. Fill in the rest of your calories with carbohydrate.

It’s that simple. For example,

- When I want to lose fat, I start my calories around 2,400 per day (I burn about 3,000 per day on average).

- My daily protein intake is around 220 grams (I generally start my cutting periods in the 190s).

- My daily fat intake is around 40 to 50 grams.

This leaves about 1,000 calories for my carbs, which means 250 carbs per day.

The Bottom Line on How Many Carbs You Should Eat

Carbohydrate intake is just given way too much attention these days, and especially for healthy, physically active people.

Their results aren’t going to hinge on how many or the types of carbs they eat. It’s going to hinge on how they manage their energy balance over time.

What’s your take on how many carbs you should eat? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Cornier MA, Donahoo WT, Pereira R, et al. Insulin sensitivity determines the effectiveness of dietary macronutrient composition on weight loss in obese women. Obes Res. 2005;13(4):703-709. doi:10.1038/oby.2005.79

- Pittas AG, Das SK, Hajduk CL, et al. A low-glycemic load diet facilitates greater weight loss in overweight adults with high insulin secretion but not in overweight adults with low insulin secretion in the CALERIE trial. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(12):2939-2941. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.12.2939

- A de Luis D, Aller R, Izaola O, Gonzalez Sagrado M, Conde R. Differences in glycaemic status do not predict weight loss in response to hypocaloric diets in obese patients. Clin Nutr. 2006;25(1):117-122. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2005.09.009

- Thomson CA, Stopeck AT, Bea JW, et al. Changes in body weight and metabolic indexes in overweight breast cancer survivors enrolled in a randomized trial of low-fat vs. reduced carbohydrate diets. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62(8):1142-1152. doi:10.1080/01635581.2010.513803

- Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Phillips SA, Jurva JW, Syed AQ, et al. Benefit of low-fat over low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial health in obesity. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):376-382. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101824

- Johnston CS, Tjonn SL, Swan PD, White A, Hutchins H, Sears B. Ketogenic low-carbohydrate diets have no metabolic advantage over nonketogenic low-carbohydrate diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(5):1055-1061. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1055

- Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, et al. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(21):2074-2081. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022637

- Volek JS, Sharman MJ, Gómez AL, et al. Comparison of energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on weight loss and body composition in overweight men and women. Nutr Metab. 2004;1. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-1-13

- Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC. A Low-Carbohydrate, Ketogenic Diet versus a Low-Fat Diet to Treat Obesity and Hyperlipidemia: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(10). doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00006

- Howarth KR, Phillips SM, MacDonald MJ, Richards D, Moreau NA, Gibala MJ. Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(2):431-438. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00108.2009

- Lane AR, Duke JW, Hackney AC. Influence of dietary carbohydrate intake on the free testosterone: Cortisol ratio responses to short-term intensive exercise training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(6):1125-1131. doi:10.1007/s00421-009-1220-5

- Creer A, Gallagher P, Slivka D, Jemiolo B, Fink W, Trappe S. Influence of muscle glycogen availability on ERK1/2 and Akt signaling after resistance exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(3):950-956. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00110.2005

- Denne SC, Liechty EA, Liu YM, Brechtel G, Baron AD. Proteolysis in skeletal muscle and whole body in response to euglycemic hyperinsulinemia in normal adults. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab. 1991;261(6 24-6). doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.6.e809

- Gelfand RA, Barrett EJ. Effect of physiologic hyperinsulinemia on skeletal muscle protein synthesis and breakdown in man. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(1):1-6. doi:10.1172/JCI113033

- Fryburg DA, Jahn LA, Hill SA, Oliveras DM, Barrett EJ. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I enhance human skeletal muscle protein anabolism during hyperaminoacidemia by different mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(4):1722-1729. doi:10.1172/JCI118217

- Bergström J, Hermansen L, Hultman E, Saltin B. Diet, Muscle Glycogen and Physical Performance. Acta Physiol Scand. 1967;71(2-3):140-150. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1967.tb03720.x

- Miller SL, Wolfe RR. Physical exercise as a modulator of adaptation to low and high carbohydrate and low and high fat intakes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:s112-s119. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600751

- Coyle EF. Substrate utilization during exercise in active people. In: American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Vol 61. American Society for Nutrition; 1995. doi:10.1093/ajcn/61.4.968S

- Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357. Accessed December 23, 2019.

- Kersten S. Mechanisms of nutritional and hormonal regulation of lipogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(4):282-286. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve071