The first thing you should know losing weight fast with exercise, is that your goal really shouldn’t be to lose weight.

Instead, your goal should be to lose fat.

You see, one of the biggest mistakes dieters make is using their scale weight as their only yardstick for success, and neglecting how their eating and exercise habits are impacting their body composition.

In other words, you do want to lose weight, but you want that weight to come from your body fat stores—not muscle mass.

Many dieters have learned this the hard way. They severely restrict their calories and do hours of cardio, often losing two to three pounds per week, but wind up losing much of their muscle mass and become disappointed with what they see in the mirror.

Luckily, there is a better way.

The truth is that the best exercise plan for weight loss is simple, easy to follow, and far more enjoyable (or at least, less unpleasant), than most people realize. It should . . .

- Preserve or even build muscle to improve your body composition.

- Burn a lot of calories to make weight loss easier and allow you to eat a reasonable amount of food.

- Be enjoyable, sustainable, and challenging.

In this article, you’re going to understand exactly what this looks like and learn how to create a weight loss exercise plan that works for you.

How to Lose Weight Fast with Exercise

The best exercise plan for weight loss has just two components:

- Lots of weightlifting.

- A moderate amount of cardio.

That’s it.

You don’t want to do just any kind of weightlifting or cardio, though. Although high-rep curls on a Bosu ball and pump classes are better than nothing, you’ll likely be disappointed in the results.

When it comes to maximizing fat loss and minimizing muscle loss, one kind of weightlifting stands head and shoulders above the rest—heavy, compound strength training.

Additionally, the right kind (and amount) of cardio can amplify your results by helping you burn fat much faster. It also improves your health in myriad ways, and lets you eat slightly more while losing weight, thus making the process more enjoyable.

If you go about cardio the wrong way, though—doing too much, at too high an intensity, or at the wrong times—it may do more harm than good.

Let’s break this down step-by-step, starting with the “king” of weight loss exercise—weightlifting.

Do Lots of Heavy, Compound Strength Training

Many fitness “gurus” recommend that you use high reps and light weights when cutting to really “bring out muscle definition.”

Psychologically, this kind of weightlifting also feels gratifying. You can literally feel your muscles burning, and this must be “burning” away some body fat, too, right?

Unfortunately, no.

While this kind of training is better than nothing, it’s not an efficient or effective way to burn fat or build muscle. In other words, you can spend hour after hour doing these kinds of workouts and still experience painfully slow progress (if any).

The only way to increase muscle definition is to gain muscle and/or reduce your body fat percentage, and the fastest and most effective way to do this is to do lots of heavy, compound strength training.

By “heavy,” I mean that you should work primarily with weights in the range of 75 to 85% of your one-rep max (1RM), which includes weights that you can do 6 to 10 reps with before reaching muscular failure. And most of the time, you should be taking your sets to the point where you feel you could only do one or two more reps before you have to stop (one to two reps short of muscular failure).

By “compound,” I mean that you should focus your efforts on exercises that train several major muscle groups at once, like the squat, deadlift, bench press, and overhead press.

There are several reasons heavy, compound strength training is best for fat loss:

- It helps build and preserve muscle mass, which makes it easier to lose weight and keep it off.

- It burns a lot of calories, which makes it easier to maintain a calorie deficit.

First, when you’re in a calorie deficit, your body is “primed” for muscle loss, but strength training counteracts this effect by increasing muscle hypertrophy (even when you’re cutting).

One salient example of the “muscle sparing” effect of strength training comes from a study conducted by scientists at West Virginia University, which found that overweight people eating just 800 calories per day were able to maintain all of their muscle mass thanks to heavy strength training.

Just lifting heavy weights isn’t enough, though—you also need to focus on increasing the weight you’re lifting over time. This process is known as progressive tension overload, and research shows it’s the primary driver of muscle growth.

Read: Is Getting Stronger Really the Best Way to Gain Muscle?

Second, although heavy strength training may not leave you in the same sweaty, heart-pounding, breathless mess as high-rep, low-weight workouts, it still burns about as many calories. This is mainly due to what’s known as the “afterburn effect,” which is the rise in metabolic rate that occurs between sets and after your workout as your body recovers.

Research shows that heavy strength training causes a much larger and more persistent rise in metabolic rate than high-rep, low-weight training. Compound exercises like the squat, bench press, and deadlift also produce a much higher spike in metabolic rate than “isolation” exercises like curls, crunches, and the like.

The bottom line is that if you want to preserve as much muscle and burn as much fat as possible when you cut, you want to do a lot of heavy pushing, pulling, and squatting.

(And if you’d like specific advice about which training program you should follow to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

Do a Moderate Amount of Low-Impact Cardio

When it comes to weight loss, the main benefit of cardio is that it burns a lot of calories.

It also offers many health and fitness benefits, including better metabolic health, more stamina, and possibly even faster post-workout recovery.

While many contrarian weight loss “experts” claim that cardio actually doesn’t burn many calories, science tells a different story.

For example, bicycling at a moderate pace (about 12 miles per hour) burns about 700 calories per hour. To burn that many calories lifting weights, you’d have to do 28 sets of heavy, compound exercises, which is not only impractical but also unsafe. Even if you could make it through this workout (unlikely), it would take almost two hours to complete.

Thus, cardio is a much more time-efficient way to burn calories than weightlifting. And since weight loss (and fat loss) largely boils down to calories in versus calories out, cardio forms an important part of the best exercise plan for weight loss.

What kind of cardio should you do, though, and how much?

You can broadly divide cardio into two categories:

- High-intensity interval training (HIIT), which involves alternating between intervals of short, maximal efforts and brief recovery periods.

- Steady-state cardio, which involves doing cardio continuously at an easy to moderate intensity.

While I used to beat the drum exclusively for HIIT, I’ve since changed my tune.

This was because I used to recommend that people do just enough cardio to achieve their body composition goals and no more. Since HIIT burns more calories per minute than steady-state cardio, it seemed like the better option, and this minimalist approach toward cardio worked well for myself and many others.

I was also excited about evidence suggesting that HIIT was inherently better for fat loss than steady-state cardio.

As research on the topic has advanced, though, we now have a better understanding of the true benefits of HIIT.

On the one hand, research clearly shows that you burn up to three to four times more calories per minute than steady-state cardio, depending on how hard you push yourself. Go HIIT.

On the other hand, research also shows that HIIT doesn’t have any magical fat-melting properties or other fat loss advantages, and that it has a few other important disadvantages compared to steady-state cardio. Boo, HIIT.

Namely, you can only do so much HIIT every week, because it causes more fatigue, muscle damage, and wear and tear on the body (and especially high-impact stuff like running sprints). This is why research shows that it tends to interfere with strength training more than steady-state cardio.

And since you can only do relatively small amounts of HIIT, the absolute number of calories you can burn per week is less substantial than many people realize.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at Colorado State University found that a 20-minute HIIT workout (4 x 30 s intervals w/ 4 min rest) burned an average of 226 extra calories over the course of the day (that’s both during the workout and from the “afterburn effect” over the following hours).

Another team of scientists at the University of Sydney published a meta-analysis on the effect of HIIT and steady-state cardio on fat loss, and found “no evidence to support the superiority of either high-intensity interval training or steady-state cardio for body fat reduction.”

In other words, both HIIT and steady-state cardio equally effective for fat loss over the long-term—it didn’t matter how people burned calories through exercise, only how many.

This is why my go-to cardio recommendation for weight loss is walking, not HIIT.

In fact, walking is better than many weightlifters realize, because it’s easy on the joints, causes little to no fatigue, and burns more calories than most people assume—about 200 to 400 per hour depending on your bodyweight and pace—and most of these calories come from body fat.

Read: The Easiest Cardio Workout You Can Do (That Actually Works)

The downside of walking is you still have to do a fair amount to burn many calories, and it doesn’t offer all of the same health benefits as moderate- or high-intensity cardio. Thus, if you want to up the intensity of your cardio workouts, here’s how to do so properly:

- Limit these types of cardio workouts to no more than 50% of the time you spend weightlifting. If you lift weights for five hours per week, don’t do over two and a half hours of moderate- or high-intensity cardio per week.

- Limit your cardio workouts to no more than thirty to forty-five minutes per session.

- Do your cardio and weightlifting on separate days if possible, and if you have to do them on the same day, try to separate them by at least six hours to minimize the cardio’s “interference effect” on your weightlifting.

- When lifting weights and doing cardio on the same day, try to schedule moderate- and high-intensity cardio workouts on days with upper-body training, and low-intensity cardio workouts on lower-body days. Additionally, do your cardio after your weightlifting, not before. This too will minimize the degree to which your cardio can interfere with your weightlifting.

- Choose low-impact types of cardio such as cycling, rowing, elliptical, and swimming over high-impact options like running or plyometrics. This will minimize muscle damage and soreness.

- Keep high-intensity interval training (HIIT) to a minimum and stick mostly to steady-state cardio.

Do that in combination with lots of heavy, compound strength training, eat properly, and you’ll soon have a body you can be proud of.

(And again, if you’d like even more specific advice about how to schedule your training to reach your health and fitness goals in as little time as possible, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz.)

Should You Exercise Fasted to Lose Weight Faster?

You’ve probably heard that training on an empty stomach helps you burn fat faster.

You’ve probably heard others say that fasted cardio is at best a waste of time and at worst a great way to burn up muscle.

Who’s right?

To get at the truth, we need to look at what happens inside your body after eating a meal.

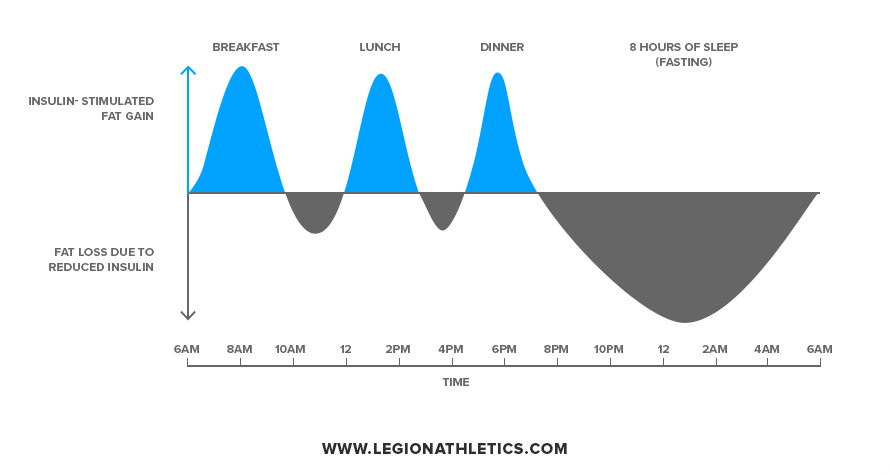

It all starts with your pancreas, which produces insulin and releases it into your blood after you eat food. Insulin’s job is to shuttle nutrients out of the blood and into your cells, such as the amino acids from protein, the glucose from carbohydrate, and the fatty acids from dietary fat.

When your insulin levels are elevated—when you’re in a “fed” state—no fat burning occurs. Your body uses the glucose in the blood for all its energy needs, and stores the excess. Depending on how much you eat, this state can last for several hours.

But, as the nutrients eaten are absorbed, insulin levels decline, and the body senses that its post-meal energy is running out. It then shifts toward burning fat stores to meet its energy needs.

Day after day, it juggles these states of storing a portion of the food you eat as fat, and burning its fat stores when food energy isn’t present. Here’s how this process looks:

When insulin is at a baseline level and your body is relying completely on its energy stores (fat, primarily), we say you’re in a “fasted” state. After you eat a moderate-sized meal, it takes three to five hours for your body to enter this state, and sometimes more depending on the size and composition of the meal.

Some research has suggested that exercising in a fasted state can burn more fat than “fed exercise,” but studies that have looked at total fat loss over time (as opposed to fat burning during a single workout) have found that fasted training doesn’t result in more total fat loss than fed training.

The reason for this is simple: while you do burn more fat during a fasted workout than a fed one, you burn less throughout the rest of the day, resulting in more or less the same total amount of fat loss.

Thus, fasted training isn’t inherently better for fat loss than fed training.

That said, the reason you want to consider fasted training when you’re cutting is that it allows you to take advantage of several supplements that do boost fat burning (one of which only works if you train fasted).

Read: Why and How I Use Fasted Cardio to Lose Fat as Quickly as Possible

The supplements I’m referring to are yohimbine, synephrine, and caffeine.

Together, these supplements increase metabolic rate, fat burning, and the release of fat from stubborn fat cells in particular, and in the case of yohimbine, it simply doesn’t work if your insulin levels are elevated, so you have to be in a fasted state to benefit from it.

Fasted training does have one significant drawback, however: accelerated muscle breakdown (and especially after workouts).

The easiest way to mitigate this without raising your insulin levels (thereby breaking your fast) is the supplement HMB, which is a powerful natural anti-catabolic agent.

You’ll find clinically effective doses of yohimbine, synephrine, and HMB in Legion’s 100% natural pre-workout fat burner, Forge, which helps you lose fat faster (and “stubborn” fat in particular), preserve muscle, and maintain training intensity and mental sharpness.

If you want to use caffeine to boost fat loss, try Phoenix, Legion’s 100% natural fat burner that speeds up your metabolism, enhances fat burning, and reduces hunger and cravings.

Conclusion

The best exercise plan for weight loss isn’t necessarily the one that burns the most calories, that makes your muscles the most swollen and sore, or that leaves you in a sweaty, exhausted heap.

Instead, the best exercise plan for weight loss revolves around heavy, compound strength training, which preserves (and even builds) muscle and burns a lot of calories (which drastically improves your body composition).

To enhance weight loss, health, and fitness further, you also want to do a moderate amount of cardio, and primarily low-impact varieties like walking, cycling, rowing, and elliptical at a moderate intensity.

Finally, if you want to do everything you can to lose fat as fast as possible, you can also try exercising fasted. This doesn’t make much of a difference in fat burning on its own, but it does allow you to take advantage of several supplements that do increase fat burning: yohimbine, synephrine, and caffeine.

Of course, the best exercise plan in the world won’t help you lose weight if you don’t follow a proper weight loss diet. Check out this article to learn what this involves:

What’s your take on this weight loss exercise plan? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Rowlands, D. S., & Thomson, J. S. (2009). Effects of β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate supplementation during resistance training on strength,body composition, and muscle damage in trained and untrained young men: A meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(3), 836–846. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a00c80

- Pitkänen, H. T., Nykänen, T., Knuutinen, J., Lahti, K., Keinänen, O., Alen, M., Komi, P. V., & Mero, A. A. (2003). Free amino acid pool and muscle protein balance after resistance exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(5), 784–792. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000064934.51751.F9

- McCarty, M. F. (2002). Pre-exercise administration of yohimbine may enhance the efficacy of exercise training as a fat loss strategy by boosting lipolysis. Medical Hypotheses, 58(6), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.1054/mehy.2001.1459

- Paoli, A., Moro, T., Marcolin, G., Neri, M., Bianco, A., Palma, A., & Grimaldi, K. (2012). High-Intensity Interval Resistance Training (HIRT) influences resting energy expenditure and respiratory ratio in non-dieting individuals. Journal of Translational Medicine, 10(1), 237. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-10-237

- Hackett, D., & Hagstrom, A. (2017). Effect of Overnight Fasted Exercise on Weight Loss and Body Composition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 2(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk2040043

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Aragon, A. A., Wilborn, C. D., Krieger, J. W., & Sonmez, G. T. (2014). Body composition changes associated with fasted versus non-fasted aerobic exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-014-0054-7

- Kraemer, W. J., Fleck, S. J., Maresh, C. M., Ratamess, N. A., Gordon, S. E., Goetz, K. L., Harman, E. A., Frykman, P. N., Volek, J. S., Mazzetti, S. A., Fry, A. C., Marchitelli, L. J., & Patton, J. F. (1999). Acute hormonal responses to a single bout of heavy resistance exercise in trained power lifters and untrained men. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology, 24(6), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1139/h99-034

- Derave, W., Mertens, A., Muls, E., Pardaens, K., & Hespel, P. (2007). Effects of post-absorptive and postprandial exercise on glucoregulation in metabolic syndrome. Obesity, 15(3), 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.548

- Surina, D. M., Langhans, W., Pauli, R., & Wenk, C. (1993). Meal composition affects postprandial fatty acid oxidation. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 264(6 33-6). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.6.r1065

- Newsholme, E. A., & Dimitriadis, G. (2001). Integration of biochemical and physiologic effects of insulin on glucose metabolism. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes, 109(SUPPL. 2). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-18575

- Schumann, M., & Rønnestad, B. R. (n.d.). Scientific Basics and Practical Applications Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training.

- Van Loon, L. J. C., Greenhaff, P. L., Constantin-Teodosiu, D., Saris, W. H. M., & Wagenmakers, A. J. M. (2001). The effects of increasing exercise intensity on muscle fuel utilisation in humans. Journal of Physiology, 536(1), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00295.x

- Wilkin, L. D., Cheryl, A., & Haddock, B. L. (2012). Energy expenditure comparison between walking and running in average fitness individuals. In Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Vol. 26, Issue 4, pp. 1039–1044). J Strength Cond Res. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822e592c

- Sabag, A., Najafi, A., Michael, S., Esgin, T., Halaki, M., & Hackett, D. (2018). The compatibility of concurrent high intensity interval training and resistance training for muscular strength and hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(21), 2472–2483. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1464636

- Treuth, M. S., Hunter, G. R., & Williams, M. (1996). Effects of exercise intensity on 24-h energy expenditure and substrate oxidation. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28(9), 1138–1143. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199609000-00009

- Tremblay, A., Simoneau, J. A., & Bouchard, C. (1994). Impact of exercise intensity on body fatness and skeletal muscle metabolism. Metabolism, 43(7), 814–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(94)90259-3

- Brown, S. P., Clemons, J. M., He, Q., & Liu, S. (1994). Prediction of the oxygen cost of the deadlift exercise. Journal of Sports Sciences, 12(4), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419408732183

- Schantz, P., Salier Eriksson, J., & Rosdahl, H. (2020). Perspectives on Exercise Intensity, Volume and Energy Expenditure in Habitual Cycle Commuting. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2, 65. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.00065

- Farinatti, P. T. V., & Castinheiras Net, A. G. (2011). The effect of between-set rest intervals on the oxygen uptake during and after resistance exercise sessions performed with large-and small-muscle mass. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(11), 3181–3190. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318212e415

- Fatouros, I. G., Chatzinikolaou, A., Tournis, S., Nikolaidis, M. G., Jamurtas, A. Z., Douroudos, I. I., Papassotiriou, I., Thomakos, P. M., Taxildaris, K., Mastorakos, G., & Mitrakou, A. (2009). Intensity of resistance exercise determines adipokine and resting energy expenditure responses in overweight elderly individuals. Diabetes Care, 32(12), 2161–2167. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-1994

- Marx, J. O., Ratamess, N. A., Nindl, B. C., Gotshalk, L. A., Volek, J. S., Dohi, K., Bush, J. A., Gómez, A. L., Mazzetti, S. A., Fleck, S. J., Häkkinen, K., Newton, R. U., & Kraemer, W. J. (2001). Low-volume circuit versus high-volume periodized resistance training in women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33(4), 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200104000-00019

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2009). Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. In Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (Vol. 41, Issue 3, pp. 687–708). Med Sci Sports Exerc. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

- Bryner, R. W., Sauers, J., Donley, D., Hornsby, G., Yeater, R., Ullrich, I. H., & Kolar, M. (1999). Effects of Resistance vs. Aerobic Training Combined With an 800 Calorie Liquid Diet on Lean Body Mass and Resting Metabolic Rate. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 18(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.1999.10718838