The pull-up is the grand poobah of bodyweight exercises.

Many people think of it as purely a lat exercise, but when performed correctly, it trains your entire back as well as your arms, shoulders, forearms, and abs.

As you’d expect, this makes the pull-up quite difficult, which is why completing your first is a major early milestone in your fitness journey.

The pull-up is also considered one of the best tests of upper body strength by everyone from your high school gym teacher to military drill instructors. Simply put, the ability to do a set of pull-ups with proper form is a badge of honor even among other fit people.

In this article, you’ll learn how to do a pull-up (or chin-up) with perfect form, the difference between the chin up vs. pull up, the best pull up alternatives, and most importantly—the best pull-up progression for doing your first-ever pull-up.

Table of Contents

+

Pull-up Muscles Worked and Benefits

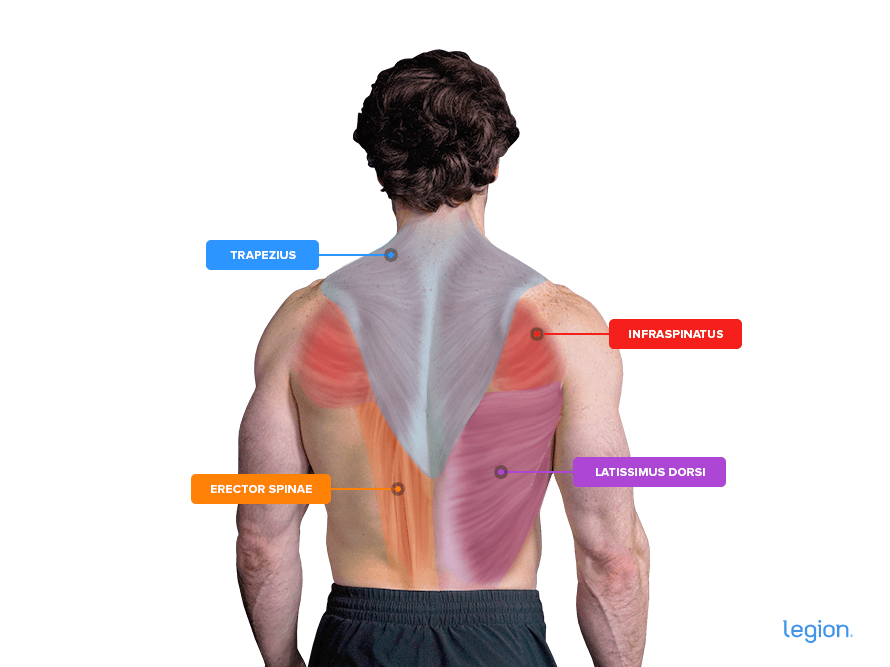

The pull-up is one of the best lat exercises you can do, but it also trains your biceps, trapezius, erector spinae, abs, and even your chest muscles to a lesser extent.

Here are the main muscles trained by the pull-up (not including the biceps):

Since the pull-up trains nearly every muscle in your back and arms, this makes it one of the best compound exercises you can do—on par with the bench press, squat, deadlift, and overhead press.

It’s unique among bodyweight exercises, too, due to how easy it is to load with additional weight as you get stronger by snatching a dumbbell between your thighs or strapping a weight plate around your waist.

Chin-up vs. Pull-up

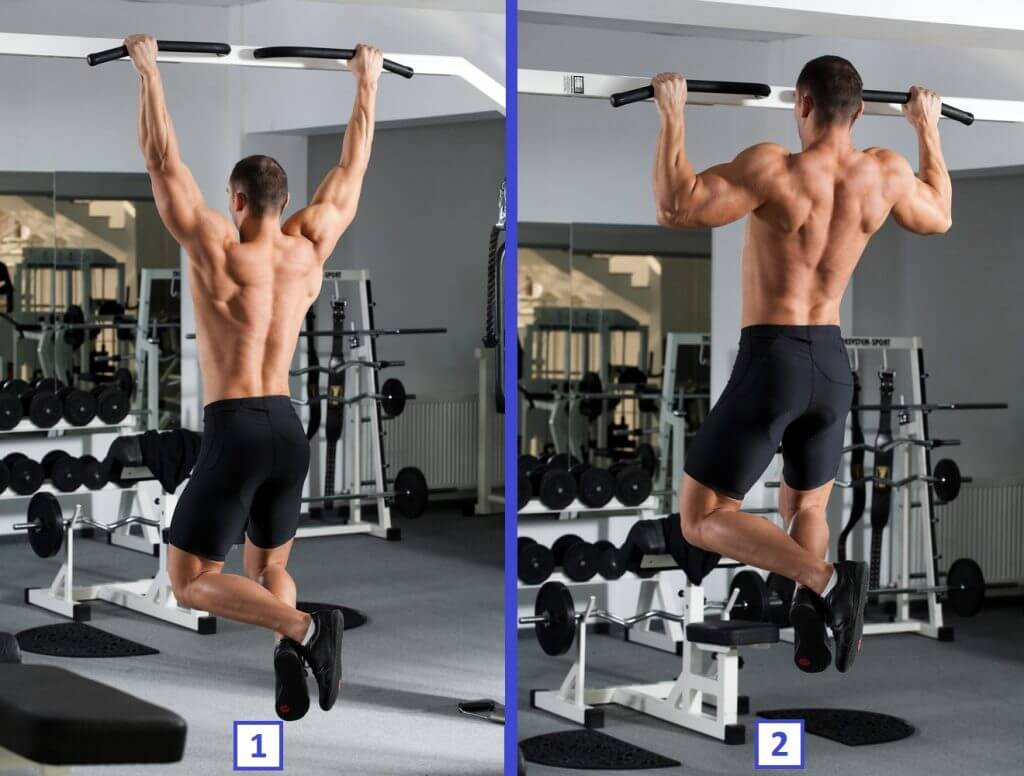

The chin-up and the pull-up are almost identical, with the only difference being how you grip the bar.

To do the chin-up, you grip the bar with your palms facing you (supinated grip). To do the pull-up, you grip the bar with your palms facing away from you (pronated grip). Most people also prefer to place their hands just outside of shoulder width apart during pull-ups and about two-to-three inches closer during chin-ups.

Research shows that this subtle difference in grip also changes which muscles are emphasized, with the pull-up being slightly better for training your lats and lower traps, and the chin-up being slightly better for training your biceps.

That said, the differences are minor, and the main reason to do one versus the other is to keep your workouts interesting and avoid overuse injuries (which are often caused by doing the same exercise over and over again).

In other words, you can use chin-ups and pull-ups interchangeably in your training, though it’s best to stick with one exercise for 8-to-12 weeks before switching to the other.

How To Do a Pull-up or Chin-up with Proper Form

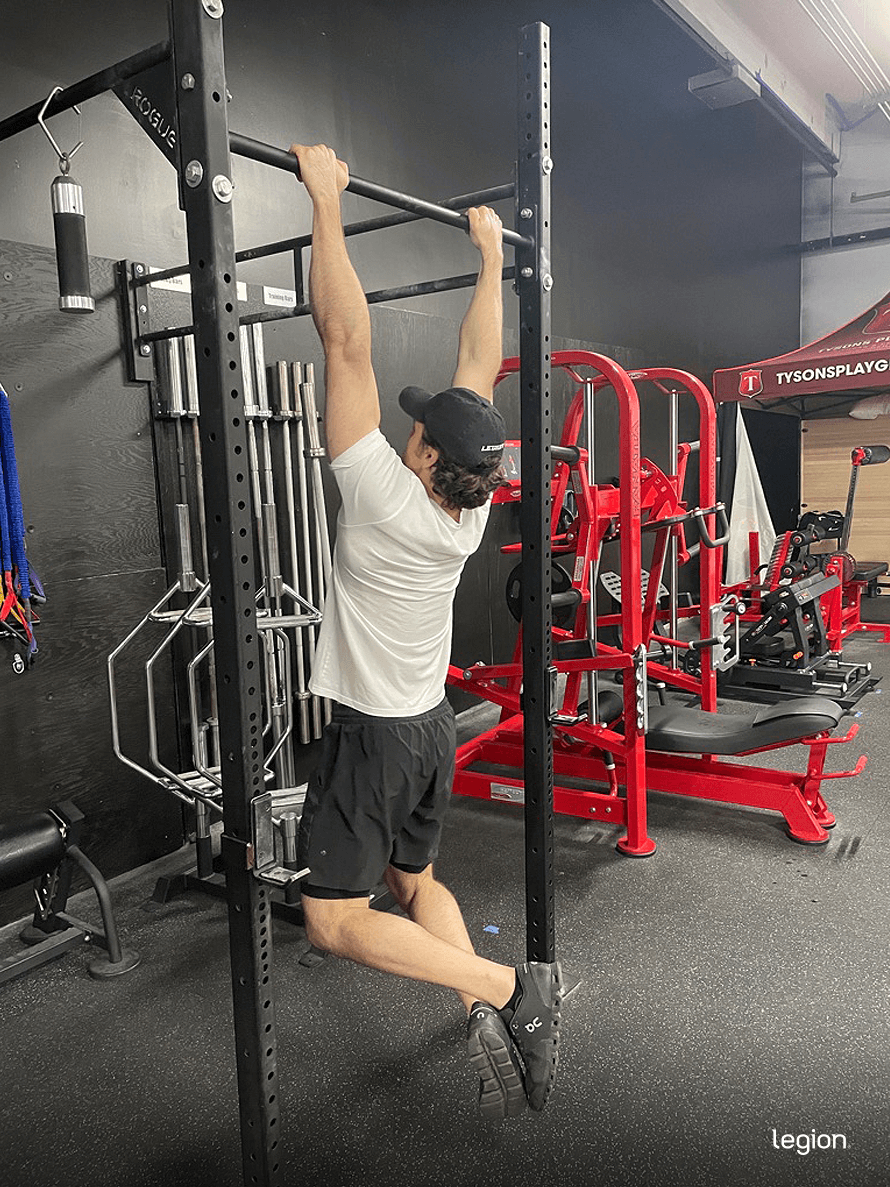

First, you’ll need a pull-up bar, set of monkey bars, or other bar or set of handles that you can hold on to. Most squat racks and cable machines also have a pull-up bar built into them.

Ideally, the bar should be about the same height as the top of your palms when your arms are fully extended overhead while standing, though it’s fine if the bar is slightly higher or lower than this.

This way, you can ensure that your knees don’t hit the ground when you’re hanging with your arms straight and that you don’t have to jump too high to reach the bar. (And if the lowest bar position is still too high for you to easily reach, put a box or bench underneath to stand on.)

Step 1: Set Up

Grip the bar with your palms facing away from you and slightly wider than shoulder width apart. You can use either a “full grip,” with your thumb wrapped around the bar opposite from your fingers, or a “false grip,” with your thumb resting next to your index finger on the bar.

The full grip tends to be more secure, although some people find it uncomfortable, so choose whichever one you prefer.

Then, lift up your feet so that you’re hanging with your arms straight. You can cross your feet over each other if you find it more comfortable.

Step 2: Ascend

Without swinging your feet or your knees, pull your body upward until your chin rises above your hands. Some helpful cues for getting this right are to think about driving your elbows into the ground or your back pockets, or smashing your chest into the bar.

The biggest mistake people make during the ascent is relaxing their muscles as their chin gets close to the bar. Make sure you pull with your full effort throughout the entire rep.

The second biggest mistake people make is swinging their knees forward to build momentum. While this does allow you to get more reps, it also makes the exercise easier and less effective. To help you fight the urge to swing your knees, think about arching your back and flexing your glutes which will help keep your lower body rigid.

Step 3: Descend

After your chin rises above the bar, lower yourself to the starting position. Keep lowering yourself until your arms are completely outstretched and you feel a deep stretch in your lats.

Many people like to make pull-ups easier by stopping the descent before their arms are completely straight. This reduces the range of motion and makes the exercise easier, but also less effective. Instead, lower your body completely to a “dead hang” before starting your next rep.

The Best Pull-up Progression

A pull-up progression is a series of exercises that helps you progress from not being able to do a pull-up to doing your first pull-up with proper form.

Here’s my favorite pull-up progression:

- Isometric holds. Get into the top position of the pull-up (with your chin above your hands) and hold this posture for as long as you can before lowering yourself to the starting position.

- Negative pull-ups. Get into the top position of the pull-up and slowly lower yourself to the bottom position, taking at least three seconds to reach the bottom of the rep.

- Assisted pull-ups. Wrap an exercise band around the pull-up bar, place your feet on the band, and do as many pull-ups as you can (the band will help support your body weight, making the exercise easier).

- Chin-ups. Most people find chin-ups slightly easier than pull-ups, which makes them a good way to train the same muscles and movement pattern.

- Pull-ups. Do your first pull-up! Once you can do at least 5 to 10 pull-ups, you can continue this pull-up progression by doing . . .

- Pull-ups + negative pull-ups. Do as many pull-ups as you can until your form starts to break down. Then, without resting, do as many negative pull-ups as you can.

- Weighted pull-ups. Snatch a dumbbell between your thighs or strap a weight plate around your waist to make the pull-ups harder. From here, progress by adding weight or doing more reps (or both).

Variation #1: Wide-grip Pull-up

Grab a pull-up bar with your palms about six inches wider than your shoulders. Without swinging your feet or your knees, pull your body upward until your chin rises above your hands, and then lower yourself to return to the starting position.

Variation #2: Weighted Pull-up

If you have a dip belt, use it to strap a weight plate around your waist. If you don’t, then squeeze the handle of a dumbbell between your thighs. Grab a pull-up bar and, without swinging your feet or your knees, pull your body upward until your chin rises above your hands, and then lower yourself to return to the starting position.

Variation #3: Negative Pull-up

Position a box or bench under a pull-up bar. Stand on the box and grab the bar. Keeping your grip on the bar, jump off the box so that your chin rises above the bar. Hold that position for a second, then lower yourself as slowly as you can until your arms are fully outstretched. Put your feet on the box again and repeat the process for the desired number of reps.

Variation #4: Kipping Pull-up

Grab a pull-up bar with a full-grip (thumbs wrapped around the bar). While hanging from the bar, flex your glutes to pull your legs back behind your body. Then, as your legs begin to swing forward, simultaneously push your shoulders back. This movement generates upward momentum, which makes it easier to pull your body toward the bar. As your body falls back to the starting position, pull your legs behind you to initiate your next rep.

Variation #5: Lat Pulldown

Adjust the thigh pad of a lat pulldown machine so that it locks your lower body in place. Stand up and grab the bar. While keeping your grip on the bar and your arms straight, sit down, allowing your body weight to pull the bar down with you. Nudge your thighs under the thigh pads and plant your feet flat on the floor.

Pull the bar toward your chest. Once the bar is underneath your chin (or touches your chest, if you want to make the exercise harder), reverse the movement to return to the starting position. (Tip: a helpful cue for this exercise is to imagine pulling your elbows into the floor).

Variation #6: Side-to-Side Pull-up

Grab a pull-up bar and pull your chest to the bar, just like a normal pull-up. Then, without dropping back to the starting position or moving your hands, pull your chest to the right so it touches your right hand, then your left hand, and then return to the starting position. That counts as one rep.

FAQ #1: How many pull-ups should you be able to do?

This depends on your weightlifting experience. Use these standards to determine how many pull-ups you should be able to do:

- Beginner: One pull-up with proper form (no swinging or assistance through a full range of motion).

- Intermediate: 10 pull-ups or one pull-up with 120% of your body weight. (That is, if you weigh 180 pounds, you’d add 35 pounds).

- Advanced: 15 pull-ups or one pull-up with 150% of your body weight.

- Exceptional: 20+ pull-ups or one pull-up with 180% of your body weight.

FAQ #2: Can you get a six pack from doing pull ups?

Not from doing pull-ups alone, but they can help improve the definition of your ab muscles.

Mind you, no single exercise can give you six-pack abs—only reducing your body fat percentage can do that. Specifically, most men need to be 10% body fat or lower and most women need to be 20% body fat or lower to have a six pack, and no amount of crunches, sit-ups, pull-ups, or other exercises can change this.

That said, research shows the pull-up is an excellent exercise for training your abs, which can make them more prominent and defined once you’re lean enough.

FAQ #3: Is it OK to do pull-ups everyday?

You can, but it’s not necessary or even ideal for improving your upper body strength and muscle mass.

In fact, doing too many pull-ups each week can quickly cause elbow and shoulder overuse injuries, which can hamstring your progress for weeks or months.

To avoid this, start by doing three to five sets of pull-ups once per week for a month. Once you can do at least 10 pull-ups in a single set, you can start doing three to five sets of pull-ups twice per week, which is enough for most people to continue making great progress.

You can do more pull-ups than this if you want, but I don’t see a good reason to unless you have a pull-up fetish to satisfy.

Scientific References +

- Hewit, J. K., Jaffe, D. A., & Crowder, T. (2018). J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports A Comparison of Muscle Activation during the Pull-up and Three Alternative Pulling Exercises. J Phy Fit Treatment & Sportsl, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.19080/JPFMTS.2018.05.555669

- Youdas, J. W., Amundson, C. L., Cicero, K. S., Hahn, J. J., Harezlak, D. T., & Hollman, J. H. (2010). Surface electromyographic activation patterns and elbow joint motion during a pull-up, chin-up, or perfect-pulluptm rotational exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3404–3414. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f1598c

- Dickie, J. A., Faulkner, J. A., Barnes, M. J., & Lark, S. D. (2017). Electromyographic analysis of muscle activation during pull-up variations. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 32, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2016.11.004