This article is an excerpt from the new third editions of Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger, my bestselling fitness books for men and women.

For me, life is continuously being hungry. The meaning of life is not simply to exist, to survive, but to move ahead, to go up, to achieve, to conquer.

—ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER

Most people view body fat as ugly, greasy flesh that must be ruthlessly exterminated, but it’s actually vital for our survival.

Not only is it an organ that helps in the creation of various important hormones, but many thousands of years ago, it was all that kept our ancient ancestors alive.

They often journeyed for days without food. Starving, they would finally kill an animal and feast, and their bodies prepared for the next bout of starvation by storing excess energy as fat.

This genetic programming is still in us, and it explains in part why so many people are overweight.

For the first time in our history, we have an endless supply of delicious, calorie-dense foods literally at our fingertips—foods that are, in many cases, carefully engineered to be as satisfying and “addictive” as possible.

(Read Michael Moss’s Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us if you want to learn the truth about the “dark side” of food science.)

Fortunately, none of this determines our destinies. Although we can’t “hack” or override this biological hardwiring, we can lose excess and unwanted body fat and maintain aesthetically pleasing (and healthy) body fat levels.

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

It’s not complicated or difficult, either. As you’ll learn in this chapter, you really only need to understand and abide by three rules to never again struggle to lose fat and keep it off.

Rule #1

Energy Balance Is King

A couple of chapters ago, you learned how energy balance alone dictates your body weight.

Eat more energy than you burn for long enough, and you’ll gain weight. Eat less, and you’ll lose weight. Period.

Although that’s all you really need to know to create a diet plan that gets the types of results that most people are after, it helps to understand how energy balance directly impacts fat storage and burning, so let’s get into that here.

Scientifically speaking, when your body is digesting and absorbing food you’ve eaten, it’s in the postprandial state (post means “after,” and prandial means “having to do with a meal”). This is also called the “fed” state.

When in this state, the body uses a portion of the energy provided by the meal to increase its fat stores. Some people call this the body’s “fat-storing mode.”

Once your body has finished digesting, absorbing, and storing the food eaten, it enters the postabsorptive state (“after absorption”). This is also called the “fasted” state.

When in this state, the body must rely mostly on its fat stores for energy. Some people call this the body’s “fat-burning mode.”

Your body flips between these fed and fasted states every day, storing small amounts of fat after meals, and then burning small amounts after food energy runs out.

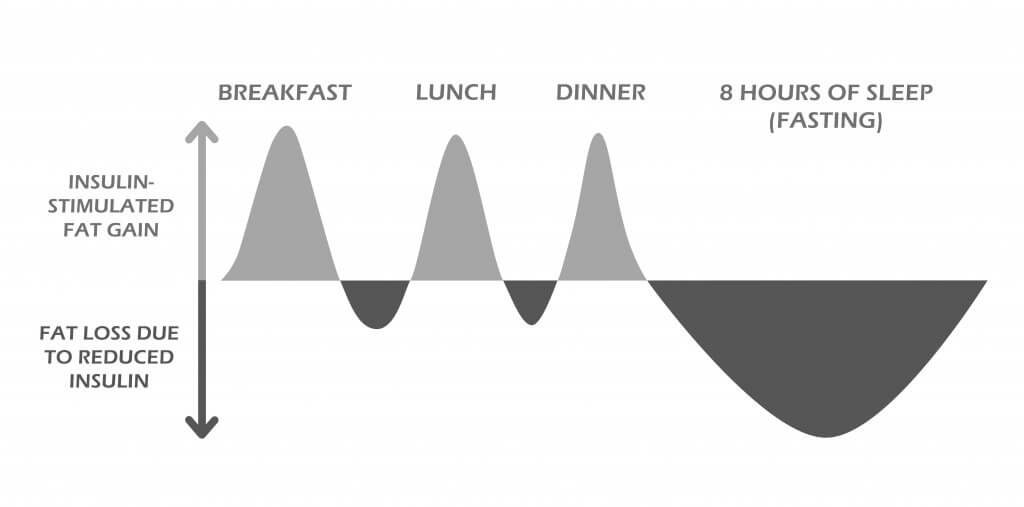

Here’s a simple graph that shows this visually:

The lighter portions are the periods where you’ve eaten and provided your body with energy to use and store as fat. The darker portions are the periods where food energy has run out, and your body has to burn fat to stay alive.

You probably also noticed the mention of insulin in the graph, which, as you know, is a hormone that causes muscles, organs, and fat tissue to absorb and use or store nutrients like glucose and amino acids.

Lately, this vital hormone has been under vicious attack by health and diet “gurus,” because it also inhibits the breakdown of fat cells and stimulates fat storage.

That is, insulin tells the body to stop burning fat for energy, and to start using and storing the energy being provided by food.

This makes sense given what you’ve just learned about fed and fasted states. Insulin tells your body whether it has food to burn or must rely on fat for energy.

This also makes insulin an easy target and scapegoat. Here’s how the story usually goes:

High-carb diet = high insulin levels = burn less fat and store more = get fatter and fatter.

And then, as a corollary:

Low-carb diet = low insulin levels = burn more fat and store less = stay lean.

This is wrong, and the “evidence” used to sell it is pseudoscience. Eating carbs does trigger insulin production, and insulin does trigger fat storage, but none of that makes you fatter. Only overeating does.

This is why a number of overfeeding studies have confirmed that the only way to cause meaningful weight gain is to eat a large surplus of calories, whether from protein, carbohydrate, or dietary fat.

Without that energy surplus, no amount of insulin or insulin-producing foods can significantly increase body fat levels.

Another gaping hole in the great insulin conspiracy is the fact that high-protein, low-carb meals can result in higher insulin levels than high-carb meals.

Research shows that whey protein raises insulin levels more than white bread, and that beef stimulates just as much insulin release as brown rice.

Furthermore, studies show that both protein and carbohydrate generally produce the same type of insulin response—a rapid rise, followed by a rapid decline.

Carbohydrate and insulin demonizers also often talk about an enzyme in your fat cells called hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), which helps release fatty acids to be burned.

Insulin suppresses the activity of HSL and thus is believed to promote weight gain, but dietary fat—the current darling of the mainstream health and diet marketing machines—suppresses it as well.

And thanks to an enzyme called acylation stimulating protein, your body doesn’t need high levels of insulin to store dietary fat as body fat.

At this point, you may want to believe what I’m telling you about energy balance, but are hung up on claims that it has been refuted by recent scientific research, or on people’s personal stories about their own experiences that seem to defy my explanations.

Let’s review a few of the more common allegations and anecdotes.

Claim #1

“I lost weight on [insert diet here] and never counted calories.”

It’s easy to find people who’ve lost significant amounts of weight without ever paying attention to how many calories they were eating.

Maybe they went low-carb. Maybe they stopped eating meat, sugar, or animal products. Or maybe they just started eating “cleaner.” And they sure lost weight.

What they don’t realize, though, is that the root cause of their weight loss wasn’t their food choices per se, but how those choices impacted their energy balance.

In other words, they lost weight because their diets kept them in a state of negative energy balance long enough for meaningful weight loss to occur, not because they ate the “right” foods and avoided the “wrong” ones.

Most weight loss diets revolve around food restriction. You have to limit or avoid foods or entire food groups, and this inevitably forces you to cut various higher-calorie fare out of your diet. Many of these higher-calorie foods also happen to be delicious and easy to overeat, like refined carbs and sugars.

Thus, when you stop eating these foods, your calorie intake naturally goes down, and the more it dips below your calorie output (expenditure), the more fat you lose.

What’s more, many people who start dieting to lose weight also start exercising or exercising more, which bumps up energy expenditure and makes it easier to maintain the calorie deficit needed to get results.

Claim #2

“I starved myself and didn’t lose weight.”

Every week, I hear from people who report no weight loss despite (allegedly) eating a small number of calories every day.

While their frustration is understandable, this doesn’t mean their metabolisms work in fundamentally different ways from everyone else’s.

What’s actually happening is almost always nothing more than a matter of human error, just like we discussed in chapter seven: accidentally eating too much and “cheating” their progress away.

Water retention is another issue that can throw many dieters for a loop.

When you restrict your calories to lose fat, especially when you do it aggressively, your body tends to retain more water. The reason for this is that calorie restriction increases production of the “stress hormone” cortisol, which in turn increases fluid retention.

Depending on your physiology, this effect can be negligible and unnoticeable, or it can be so strong that it completely obscures several weeks of fat loss. In this way, people can lose fat for several weeks without losing weight and conclude that calorie counting “doesn’t work.”

Later in this book, you’ll learn how to make sure you don’t make the same mistake.

Claim #3

“If you eat clean, calories don’t matter.”

If all we’re talking about is body weight, then a calorie is very much a calorie, and “clean” calories count just as much as “dirty” ones.

That said, it’s accurate to say that “clean” or “healthy” foods are more conducive to weight loss and maintenance than “dirty” or “unhealthy” ones, because they’re generally lower in calories and harder to overeat.

Think about it for a second. What’s most likely to lead to excess calorie consumption, “dirty” foods like pizza, cheeseburgers, candy, and ice cream, or “clean” ones like chicken breast, broccoli, brown rice, and apples?

This is why getting the majority of your daily calories from “diet-friendly” foods makes for easier and more enjoyable weight loss and maintenance.

Claim #4

“The human body isn’t an inorganic machine. You can’t apply the same rules.”

Some people say that the first law of thermodynamics doesn’t apply to the human metabolism. They say our bodies are far more complicated than the simple engines that power our refrigerators and cars.

Their arguments can be convincing, too, chock-full of weasel words like entropy, chaos theory, and metabolic advantage, and tangents on the more esoteric aspects of our endocrine system.

This is all smoke and mirrors.

It’s true that the human body is far more complex than a combustion engine, but as I mentioned earlier, there’s a reason why every single controlled weight loss study conducted in the last century has concluded that meaningful weight loss requires “calories in” to be lower than “calories out.” It works the same in the lean and obese, and even in the healthy and diseased.

Energy balance is a first principle of the human metabolism, the “master key” to your body weight, and it simply can’t be circumvented or ignored.

Rule #2

Macronutrient Balance Is Queen

You’ve heard me say that as important as energy balance is, it’s not the whole story, especially not when the goal is to improve your body composition.

Well, it’s time to hear the rest of the weight loss tale, and this is the final act.

Macronutrient balance refers to how the calories you eat break down into protein, carbohydrate, and dietary fat.

If you want to lose fat and not muscle, or gain muscle and not fat, then you need to pay close attention to both your energy and macronutrient balances.

In this context, a calorie is no longer a calorie because a calorie of protein does very different things in your body than a calorie of carbohydrate or dietary fat.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these “macros” and discover how they fit into the fat loss puzzle.

Macronutrient #1

Protein

While the scientific search for the “One True Diet” continues, there’s one thing we know for certain: it’s going to be high in protein.

Study after study has already confirmed that high-protein dieting is superior to low-protein dieting in just about every meaningful way. Specifically, research shows that people who eat more protein:

- Lose fat faster

- Gain more muscle

- Burn more calories

- Experience less hunger

- Have stronger bones

- Generally enjoy better moods

Protein intake is even more important when you exercise regularly because this increases your body’s demand for protein.

It’s also important when you restrict your calories to lose fat, because eating adequate protein plays a major role in preserving lean mass while dieting.

Protein intake is important among sedentary folk as well. Studies show that such people lose muscle faster as they age if they don’t eat enough protein, and the faster they lose muscle, the more likely they are to die from all causes.

Macronutrient #2

Carbohydrate

To really understand why carbs aren’t your enemy, let’s briefly discuss their chemical structure and what happens when you eat them.

There are four primary forms of carbohydrate that you need to know about:

- Monosaccharides

- Disaccharides

- Oligosaccharides

- Polysaccharides

Monosaccharides are often called simple sugars because they have a very simple structure. Mono means “one” and saccharide means “sugar,” so “one sugar.”

There are three monosaccharides: glucose, fructose, and galactose. You learned these words earlier in this book, but let’s brush up on them quickly here.

- Glucose is a sugar that occurs widely in nature and is an important energy source in organisms, as well as a component of many carbohydrates.

- Fructose is a sugar found in many fruits and honey, as well as processed products like table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup.

Fructose is converted into glucose by the liver and then released into the blood for use.

- Galactose is a sugar found in dairy products that’s metabolized similarly to fructose.

Disaccharides, meaning “two sugars,” are commonly found in nature as sucrose, lactose, and maltose. Again, a quick review of the two terms you’re familiar with, and then the new, third term:

- Sucrose is a sugar that occurs naturally in most plants and is obtained commercially especially from sugarcane or sugar beets.

It’s commonly known as table sugar.

- Lactose is a sugar present in milk that contains glucose and galactose.

- Maltose is a sugar that consists of two glucose molecules linked together.

It’s uncommon in nature and is used in alcohol production.

Oligosaccharides are molecules that contain several monosaccharides linked together in chain-like structures. Oligos is Greek for “a few,” so a “few sugars.”

The fiber found in plants is partially made of oligosaccharides, and many vegetables also contain fructooligosaccharides, which are short chains of fructose molecules.

Another common form of oligosaccharide that we eat is raffinose, a chain of galactose, glucose, and fructose. This is found in a variety of foods like whole grains, beans, cabbage, Brussel sprouts, broccoli, asparagus, and other vegetables.

Galactooligosaccharides round out this list, and they’re short chains of galactose molecules found in many of the same foods as raffinose. They’re indigestible but play a role in stimulating healthy bacteria growth in the gut.

The last form of carbohydrate that we need to discuss is the polysaccharide, which is a long chain of monosaccharides, usually containing 10 or more of these sugars.

Starch (the energy stores of plants) and cellulose (a natural fiber found in many plants) are two examples of polysaccharides that we often eat. Our bodies easily break starches down into glucose, but cellulose passes through our digestive system intact.

Except for those that aren’t digested, all these types of carbs have something very important in common: they all end up as glucose in the body.

Whether we’re talking about the natural sugars found in fruit, the processed ones found in a candy bar, or the “healthy” ones found in green vegetables, they’re all digested into glucose and shipped off in the blood for use.

The key difference between these forms of carbohydrate is the rate at which this conversion happens.

The candy bar turns into glucose rather quickly because it contains a large number of quickly digested monosaccharides, whereas the broccoli takes longer because it contains slower-burning oligosaccharides.

Some people say that makes all the difference—that the speed with which carbs are converted into glucose determines whether they’re “healthy.” These people are mostly wrong.

For instance, baked potato is rather high on the glycemic index (85) but packed with vital nutrients. Watermelon is up there on the index as well (72), and even oatmeal (58) is higher than a Snickers Bar (55).

Does that mean you can eat all the simple sugars you want, then? That so long as you keep your energy and macronutrients balanced, you can replace potato and oatmeal with soda and candy as often as you’d like?

Well, you could, but it would eventually catch up with you because our bodies need to get a lot more than calories and macros from the food we eat. They also need a long list of nutrients, like vitamins, minerals, and fiber, that simply aren’t in Coca-Cola and Twizzlers.

This is one of the reasons why research shows there’s an association between high added sugar intake—sugars like sucrose and fructose added to foods to sweeten them—and several metabolic abnormalities and health conditions, including obesity, as well as varying degrees of nutritional deficiency.

There’s simply no denying that eating too much added sugar can harm our health and that reducing intake is generally a good idea.

That doesn’t mean we need to reduce or limit our consumption of all forms of carbohydrate, however. In fact, if you’re healthy and physically active, particularly if you lift weights regularly, chances are that you’ll do better with more carbs in your diet, not less.

You’ll find out why in the next chapter.

Macronutrient #3

Dietary Fat

Dietary fat doesn’t deserve all the attention it’s getting these days.

You should eat enough to stay healthy, but have no reason to follow a high-fat diet unless you really enjoy it. And even then you need to do so with caution.

To understand why, let’s start at the top. There are two different types of fat found in food:

- Triglycerides

- Cholesterol

Triglycerides make up the bulk of our daily fat intake and are found in a wide variety of foods ranging from dairy to nuts, seeds, meat, and more.

They can be liquid (unsaturated) or solid (saturated), and they support health in many ways. They help absorb vitamins, they’re used to create various hormones, they keep the skin and hair healthy, and much more.

We recall that saturated fat is a form of fat that’s solid at room temperature and found in foods like meat, dairy, and eggs.

The long-held belief that saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease has been challenged by recent research, which claims “that there is no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of CHD or CVD [heart disease].”

The fad diet industry has exploited this “revelation” marvelously with runaway hits like the paleo and ketogenic diets.

The problem, however, is that much of the scientific literature used to promote these diets has also been severely criticized by prominent nutrition and cardiology researchers for various flaws and omissions.

These scientists maintain that there is a strong association between high intake of saturated fat and heart disease, and that we should follow the generally accepted dietary guidelines for saturated fat intake (less than 10 percent of daily calories) until we know more.

Given the current weight of the evidence, nobody can honestly claim that we can all eat as much saturated fat as we want without any chance of negative consequences.

This is why I think it’s much smarter to “play it safe” and wait for further research before joining in the mainstream saturated fat orgy.

Earlier in this book, you learned that unsaturated fat is a form of fat that’s liquid at room temperature and found in foods like olive oil, avocado, and nuts. There are two distinct types of unsaturated fats:

- Monounsaturated fat

- Polyunsaturated fat

Monounsaturated fat is liquid at room temperature and starts to solidify when cooled. Foods high in monounsaturated fat include nuts, olive and peanut oil, and avocado.

Polyunsaturated fat is liquid at room temperature and remains so when cooled. Foods high in polyunsaturated fat include safflower, sesame, and sunflower seeds, corn, and many nuts and their oils.

Unlike saturated fat, there’s no controversy over monounsaturated fat. Research shows that it can reduce the risk of heart disease, and it’s also believed to be responsible for some of the health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet, which involves eating a lot of olive oil.

Polyunsaturated fat, on the other hand, isn’t as cut-and-dried. The two primary polyunsaturated fats are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and linoleic acid (LA). ALA is what’s known as an omega-3 fatty acid while LA is an omega-6 fatty acid. These designations refer to the structure of the molecules.

ALA and LA are the only types of fat that our bodies can’t produce and that we must obtain from our diets. This is why they’re referred to as essential fatty acids.

These two substances cause an enormous number of effects in the body. The chemistry is complex, but here’s what you need to know for the purpose of our current discussion:

- LA is converted into several compounds in the body, including the anti-inflammatory gamma-linolenic acid, as well as the pro-inflammatory arachidonic acid.

- ALA can be converted into an omega-3 fatty acid known as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), which can be converted into another called docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

A large amount of research has been done on EPA and DHA, and it appears that they bestow many, if not all, of the health benefits generally associated with ALA, including:

- Decreased inflammation

- Improved mood

- Faster muscle growth

- Increased cognitive performance

- Faster fat loss

It’s an oversimplification to say that the effects of LA (omega-6) are generally “bad,” and the effects of ALA (omega-3) are generally “good,” but it’s more accurate than inaccurate.

That’s why it has been hypothesized that a diet too high in omega-6 and too low in omega-3 fatty acids can cause a whole host of health problems.

Research conducted by scientists at the University of Illinois casts doubt on this, though. There’s no question that inadequate omega-3 intake is bad for your health, but ironically, studies have found that increasing omega-6 intake can decrease the risk of heart disease, not increase it.

Thus, scientists suspect that the absolute amount of omega-3 fatty acids in the diet is more important than the ratio between omega-3 and omega-6 intakes. Hence the considerable amount of work that has been done to boost the omega-3 content of various foods like eggs and meat.

The key takeaway here is if you’re like most people, you’re getting enough omega-6 fatty acids in your diet, but probably not enough omega-3s (and EPA and DHA in particular). An easy way to fix this is with an omega-3 supplement, which we’ll discuss later in this book.

Cholesterol is the other type of fat found in food. It’s a waxy substance present in all cells in the body, and it’s used to make hormones, vitamin D, and substances that help you digest your food.

Several decades ago, it was believed that foods that contained cholesterol, like eggs and meat, increased the risk of heart disease. We now know it’s not that simple. Eggs, for instance, have been more or less exonerated, and studies show that processed meat is associated with high incidence of heart disease but red meat per se is not.

One of the reasons the relationship between cholesterol and heart health is tricky is foods that contain cholesterol also often contain saturated fat, which can indeed increase the risk of heart disease.

Another reason has to do with how cholesterol travels throughout your body. It’s delivered to cells by molecules known as lipoproteins, which are made out of fat and proteins. There are two kinds of lipoproteins:

- Low-density lipoproteins (LDL)

- High-density lipoproteins (HDL)

When people talk of “bad” cholesterol, they’re referring to LDL because research shows that high levels of LDL in your blood can lead to an accumulation in your arteries, and increase the risk of heart disease.

This is why foods that can raise LDL levels, such as fried and processed foods and foods high in saturated fat, are generally considered bad for your heart.

HDL is often thought of as the “good” cholesterol because it carries cholesterol to your liver, where it’s processed for various uses.

Rule #3

Adjust Your Food Intake Based on How Your Body Is Responding

Tweaking your calories and macros up and down based on what’s actually happening with your body is vitally important for two reasons:

- Formulas for calculating your calories and macros may not work perfectly for you right out of the box.

- What has been working can stop producing results.

To the first point, your metabolism may be naturally faster or slower than the formulas assume. You may engage in a lot of spontaneous activity throughout the day without realizing it, like walking around while on the phone, hopping to the bathroom, drumming your fingers while you read, or bobbing your legs while you think. Your job or hobbies may burn more energy than you realize (causing you to underestimate your energy expenditure), and you may burn more (or less) energy than average during exercise.

And to the second point, we recall that the body responds to calorie restriction with countermeasures meant to stall weight loss, including metabolic slowdown. This is the primary reason why a calorie intake that initially results in weight loss can eventually stop working.

Similarly, the body responds to a calorie surplus with countermeasures meant to stall weight gain, including metabolic speedup. This is mostly why a calorie intake that initially results in weight gain can also eventually stop working.

The good news is you don’t have to try to account for all this before beginning your fat loss diet. Instead, you can start simple and adjust your calories and macros based on how your body is actually responding.

Here’s the basic rule of thumb:

If you’re trying to lose weight but aren’t, you probably need to eat less or move more.

(And if you’re trying to gain weight but aren’t, you probably just need to eat more.)

We’ll talk more about this, including what you should do when you stop losing weight, later in this book.

#

Phew, you made it.

You’ve just learned the biggest dietary “secrets” to building your best body ever. The material is dry, but so are most principles of most everything you could want to learn.

Remember that the value of information isn’t determined by how it makes you feel but by how well you understand it and how workable it is.

You’ve also learned that losing fat quickly and healthily without losing muscle isn’t complicated or even all that difficult, really.

It takes a bit of guidance and discipline, but once you know how to put everything you’ve just learned in this chapter into practice (and you will soon), you might be surprised at how smoothly it can go.

In fact, this “flexible” style of dieting will probably be the easiest you’ve ever tried, and the most effective and sustainable. Exciting, right?

Key Takeaways

- When your body is digesting and absorbing food you’ve eaten, it’s in the postprandial state. This is also called the “fed” state.

- Once your body has finished digesting, absorbing, and storing the food eaten, it enters the postabsorptive state. This is also called the “fasted” state.

- Your body flips between fed and fasted states every day, storing small amounts of fat after meals, and then burning small amounts when there’s no food energy left.

- Without an energy surplus, no amount of insulin or insulin-producing foods can significantly increase body fat levels.

- When you restrict your calories to lose fat, especially when you restrict them aggressively, you tend to retain more water.

- If all we’re talking about is body weight, then a calorie is very much a calorie, and “clean” calories count just as much as “dirty” ones.

- “Clean” or “healthy” foods are more conducive to weight loss than “dirty” or “unhealthy” ones because they’re generally lower in calories and harder to overeat.

- Getting the majority of your daily calories from “diet-friendly” foods when dieting for fat loss makes for a much easier, more enjoyable dieting experience.

- Macronutrient balance refers to how the calories you eat break down into protein, carbohydrate, and dietary fat.

- If you want to lose fat and not muscle, or gain muscle and not fat, then you need to pay close attention to both your energy and macronutrient balances.

- People who eat more protein lose fat faster, gain more muscle, burn more calories, experience less hunger, have stronger bones, and generally enjoy better moods.

- Protein intake is even more important when you exercise regularly because this increases your body’s demand for it.

- Whether we’re talking about the natural sugars found in fruit, the processed ones found in a candy bar, or the “healthy” ones found in green vegetables, they’re all digested into glucose and shipped off to the brain, muscles, and organs for use.

- There’s no difference in weight loss between people whose diets contain a large amount of high-glycemic foods versus those that focus on low-glycemic foods.

- There’s an association between high sugar intake and several metabolic abnormalities and adverse health conditions, including obesity, as well as varying levels of nutritional deficiencies.

- When dieting to lose fat, high-protein, high-carbohydrate dieting allows you to push harder in your workouts and maintain more muscle mass.

- We should eat at least enough dietary fat to support our health and only raise intake beyond that based on our goals, fitness, and preferences.

- Triglycerides make up the bulk of our daily fat intake and are found in a wide variety of foods ranging from dairy to nuts, seeds, meat, and more.

- Saturated fat is a form of fat that’s solid at room temperature and found in foods like meat, dairy, and eggs.

- There’s a strong association between high intake of saturated fat and heart disease, and we should follow the generally accepted dietary guidelines for saturated fat intake (less than 10 percent of daily calories) until we know more.

- Monounsaturated fat can reduce the risk of heart disease, and it’s believed to be responsible for some of the health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet, which involves eating a lot of olive oil.

- The absolute amount of omega-3 fatty acids in the diet is more important than the ratio between omega-3 and omega-6 intakes.

- If you’re like most people, you’re getting enough omega-6 fatty acids in your diet, but probably not enough omega-3s (EPA and DHA in particular).

- Cholesterol is the other type of fat found in food. It’s a waxy substance present in all cells in the body, and it’s used to make hormones, vitamin D, and substances that help you digest your food.

- Scientists used to believe that foods that contained cholesterol increased the risk of heart disease, but we now know that this isn’t the case.

- When people talk of “bad” cholesterol, they’re referring to LDL. High levels of LDL in your blood can lead to an accumulation in your arteries and increase the risk of heart disease.

- If you’re trying to lose weight but aren’t, you probably need to eat less or move more.

- If you’re trying to gain weight but aren’t, you probably just need to eat more.

This article is an excerpt from the new third editions of Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger, my bestselling fitness books for men and women, which are currently on sale for just 99 cents.

Scientific References +

- JI, P., PT, J., IA, B., R, C., I, E., MB, K., PM, K.-E., D, K., BM, M., RP, M., KR, N., M, R., & M, U. (2011). The importance of reducing SFA to limit CHD. The British Journal of Nutrition, 106(7), 961–963. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451100506X

- C, B., A, K., PM, K., L, B., G, B., C, P., A, K., T, S., R, P., R, C., & R, S. (2005). Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet (London, England), 366(9493), 1267–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1

- I, Z., JJ, B., M, B.-R., J, W., C, de la F.-A., S, B., Z, V., & MA, M.-G. (2011). Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in the SUN Project. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65(6), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/EJCN.2011.30

- WC, W. (2007). The role of dietary n-6 fatty acids in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine (Hagerstown, Md.), 8 Suppl 1(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.2459/01.JCM.0000289275.72556.13

- GH, J., & K, F. (2012). Effect of dietary linoleic acid on markers of inflammation in healthy persons: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(7). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAND.2012.03.029

- C, C., J, D., P, R., JM, A., & F, L. (1997). Effect of dietary fish oil on body fat mass and basal fat oxidation in healthy adults. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders : Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21(8), 637–643. https://doi.org/10.1038/SJ.IJO.0800451

- MF, M., CM, R., L, S., JK, Y., SM, C., & SB, M. (2010). Serum phospholipid docosahexaenonic acid is associated with cognitive functioning during middle adulthood. The Journal of Nutrition, 140(4), 848–853. https://doi.org/10.3945/JN.109.119578

- GI, S., P, A., DN, R., BS, M., D, R., MJ, R., & B, M. (2011). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinaemia-hyperaminoacidaemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clinical Science (London, England : 1979), 121(6), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20100597

- ME, S., SP, E., AL, G., & JJ, M. (2011). Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(12), 1577–1584. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10M06634

- RJ, B., DE, L., KH, F.-W., AJ, G., & BK, S. (2009). Effect of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid on resting and exercise-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers: a randomized, placebo controlled, cross-over study. Lipids in Health and Disease, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-8-36

- L, S., & G, H. (2014). Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lipids in Health and Disease, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-13-154

- JI, P., PT, J., IA, B., R, C., I, E., MB, K., PM, K.-E., D, K., BM, M., RP, M., KR, N., M, R., & M, U. (2011). The importance of reducing SFA to limit CHD. The British Journal of Nutrition, 106(7), 961–963. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451100506X

- PW, S.-T., Q, S., FB, H., & RM, K. (2010). Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(3), 535–546. https://doi.org/10.3945/AJCN.2009.27725

- RK, J., LJ, A., M, B., BV, H., M, L., RH, L., F, S., LM, S., & J, W.-R. (2009). Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 120(11), 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627

- EJ, M., LA, T., M, S., & R, C. (2002). Skeletal muscle strength as a predictor of all-cause mortality in healthy men. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 57(10), B359–B365. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONA/57.10.B359

- JW, K., HS, S., MJ, D., & B, L.-H. (2006). Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression 1. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(2), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/83.2.260

- SM, P., & LJ, V. L. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29 Suppl 1(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.619204

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2014 11:1, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- WW, C., & M, T. (2010). Protein intake, weight loss, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65(10), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONA/GLQ083

- D, P.-J., E, W., RD, M., RR, W., A, A., & M, W.-P. (2008). Protein, weight management, and satiety. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(5). https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/87.5.1558S

- Westerterp, K. R. (2004). Diet induced thermogenesis. Nutrition & Metabolism, 1, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-1-5

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2014 11:1, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- EM, E., MC, M., MP, T., RJ, V., PM, K.-E., & DK, L. (2012). Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: a randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutrition & Metabolism, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-55

- ER, H., C, Z., DS, R., R, N., & J, C. (2015). High-protein, low-fat, short-term diet results in less stress and fatigue than moderate-protein moderate-fat diet during weight loss in male weightlifters: a pilot study. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 25(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSNEM.2014-0056

- KD, H., T, B., R, B., KY, C., A, C., EJ, C., S, G., J, G., L, H., ND, K., BV, M., CM, P., M, S., MC, S., M, W., PJ, W., & L, Y. (2015). Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity. Cell Metabolism, 22(3), 427–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CMET.2015.07.021

- AJ, T., T, M., D, V., JM, H., J, D., & SE, T. (2010). Low calorie dieting increases cortisol. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0B013E3181D9523C

- S, M., MC, C., CG, B., RJ, D., S, B., & DW, E. (2001). Insulin mediated inhibition of hormone sensitive lipase activity in vivo in relation to endogenous catecholamines in healthy subjects. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 86(9), 4193–4197. https://doi.org/10.1210/JCEM.86.9.7794

- K, E., ML, C., & KN, F. (1999). Effects of an oral and intravenous fat load on adipose tissue and forearm lipid metabolism. The American Journal of Physiology, 276(2). https://doi.org/10.1152/AJPENDO.1999.276.2.E241

- S, P., & V, E. (2010). The acute effects of four protein meals on insulin, glucose, appetite and energy intake in lean men. The British Journal of Nutrition, 104(8), 1241–1248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510001911

- A, S., U, G., SJ, M., E, O., JJ, H., I, B., & P, R. (2012). The insulinogenic effect of whey protein is partially mediated by a direct effect of amino acids and GIP on β-cells. Nutrition & Metabolism, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-48

- S, P., & V, E. (2010). The acute effects of four protein meals on insulin, glucose, appetite and energy intake in lean men. The British Journal of Nutrition, 104(8), 1241–1248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510001911

- Alex Leaf, & Jose Antonio. (n.d.). The Effects of Overfeeding on Body Composition: The Role of Macronutrient Composition - A Narrative Review - PubMed. Retrieved August 31, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29399253/

- Kersten, S. (2001). Mechanisms of nutritional and hormonal regulation of lipogenesis. EMBO Reports, 2(4), 282. https://doi.org/10.1093/EMBO-REPORTS/KVE071