It’s estimated that there are over 2+ million scientific papers published each year, and this firehose only seems to intensify.

Even if you narrow your focus to fitness research, it would take several lifetimes to unravel the hairball of studies on nutrition, training, supplementation, and related fields.

This is why my team and I spend thousands of hours each year dissecting and describing scientific studies in articles, podcasts, and books and using the results to formulate our 100% all-natural sports supplements and inform our coaching services.

And while the principles of proper eating and exercising are simple and somewhat immutable, reviewing new research can reinforce or reshape how we eat, train, and live for the better.

Thus, each week, I’m going to share three scientific studies on diet, exercise, supplementation, mindset, and lifestyle that will help you gain muscle and strength, lose fat, perform and feel better, live longer, and get and stay healthier.

This week, you’ll learn whether you should train less intensely when you’re tired, how fast you can lose fat if you’re overweight, and how to improve your odds of achieving your New Year’s resolutions.

Sometimes, easier workouts make you stronger than hard ones.

Source: “Flexible nonlinear periodization in a beginner college weight training class” published in January 2010 in Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Some days you just don’t feel like working out.

What to do?

Should you grit your teeth and grind out a less-than-stellar workout? Or ease your foot off the gas for a day and come back revitalized tomorrow?

While the first approach is laudable and sometimes necessary, more and more research suggests the second may be superior in most cases.

A good example of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at St. Francis College, which split 16 newbie weightlifters into 2 groups.

Both groups trained twice weekly for 12 weeks, performing exercises such as the leg press, leg curl, squat, deadlift, and lunge for the lower body, and the chest press, bench press, row, lat pulldown, shoulder press, and dumbbell rear lateral raise for the upper body.

Throughout the study, both groups did the same amount of volume (sets and reps) using the same intensities. The only difference between the groups was that one group had to stick rigidly to the workout plan the researchers gave them, whereas the other group was allowed to be more flexible depending on how they felt.

For example, during the first 4 weeks of the program, the “rigid” group had to do ~20 reps per set in their first 3 workouts, ~15 reps per set in their following 3 workouts, and ~10 reps per set in their final 3 workouts.

Conversely, the “flexible” group could decide whether they wanted to do 20-, 15-, or 10-rep sets immediately before each workout, depending on whether they felt fresh or ragged.

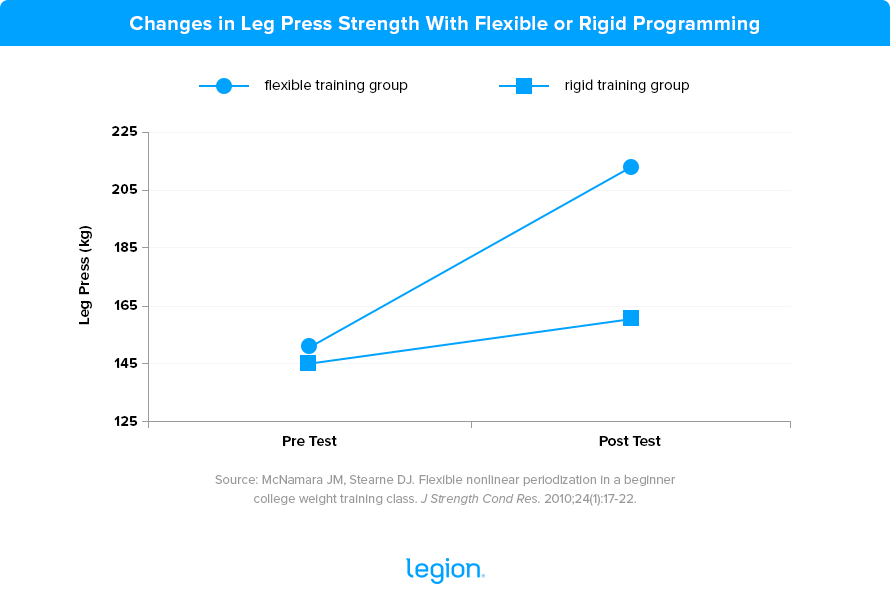

The results showed that the flexible training groups gained significantly more leg press strength than the rigid training group. Here’s a graph to illustrate:

Interestingly, both groups gained similar amounts of strength on the chest press. However, the researchers believed this was because both programs included too much upper-body training. So much, in fact, that none of the weightlifters were able to recover between workouts, causing them to underperform.

These results are in step with other similar studies.

For example, in a study conducted by researchers at South Florida University, powerlifters who used flexible programming only missed 4 workouts during the 9-week study. In contrast, those who used rigid programming missed 8 workouts. In other words, flexible programming helped dedicated weightlifters stick to their program better.

Other studies show that you’ll probably gain more strength by resting as long as you feel you need to between sets rather than using predetermined rest periods, too.

The most obvious downside of flexible programming is that it requires more judgment on your part, which may increase the chances of you “going easy” on yourself, even when you don’t need a break.

If you’re susceptible to this, working with an experienced coach is a good way to ensure you make sound, productive decisions.

(And if you’d like expert guidance on everything you need to build your best body ever, including exercise technique coaching, custom diet and training plans, emotional encouragement, accountability, and more, contact Legion’s VIP one-on-one coaching service to set up a free consultation. Click here to check it out.)

If this isn’t a concern, and you think allowing wiggle room in your program would help you progress, here’s what I recommend:

- Pick a weightlifting program.

- Stick to the program most of the time.

- If, on occasion, you don’t feel capable of completing your planned workout, make a reasonable alteration that makes it doable.

For example, if you follow my 5-day Bigger Leaner Stronger program and don’t feel up to 3 sets of 4-to-6 reps of the deadlift, lighten the load and do 3 sets of 6-to-8 or 8-to-10 reps instead. Alternatively, decrease the number of sets you do—1 or 2 is fine if that’s all you can muster.

Likewise, if you usually rest at the weekend but feel drained after your Monday workout, take Tuesday off. Then, move all your other workouts back a day, or forget about Tuesday’s workout and start next week like a blank slate.

TL;DR: Decreasing your workout volume and intensity on days when you feel too tired to train hard can help you gain more strength over the long term.

The upside of being overweight: you can lose fat very fast without losing muscle.

Source: “A time-efficient reduction of fat mass in 4 days with exercise and caloric restriction” published on January 20, 2014 in Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports.

You’ve probably heard that you should aim to lose about one pound a week while dieting.

And that’s not bad advice.

But what if you have 25, 50, or 100+ pounds to lose?

Losing just one pound per week means you’ll be dieting for months, if not years, which is a bitter pill to swallow if you’ve tried and failed to lose weight before.

Here’s the good news: you can lose weight much faster than this if you’re very overweight.

Evidence of this comes from a study conducted by scientists at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, in which 15 overweight men followed a brutal diet and workout program for 4 days.

The dieters ate just 10% of the total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) per day, with all of their calories coming from whey protein or sugar.

They also did about 9 hours of cardio per day, which ensured they maintained a daily calorie deficit of 5,000 calories.

After 4 days, they lost 4.4 pounds of body fat on average. Although they technically lost about 6.6 pounds of lean mass, most of this was water weight. After they rehydrated, the researchers found the dieters only lost about two pounds of actual muscle.

Based on this, you could say that an upper limit for fat loss is about one pound per day.

The problem, of course, is that this is also totally unrealistic and unworkable for more than a few days. And while little sprints of weight loss like this look nice on paper, they’re a drop in the bucket if you have a lot of fat to lose.

What’s a more reasonable target?

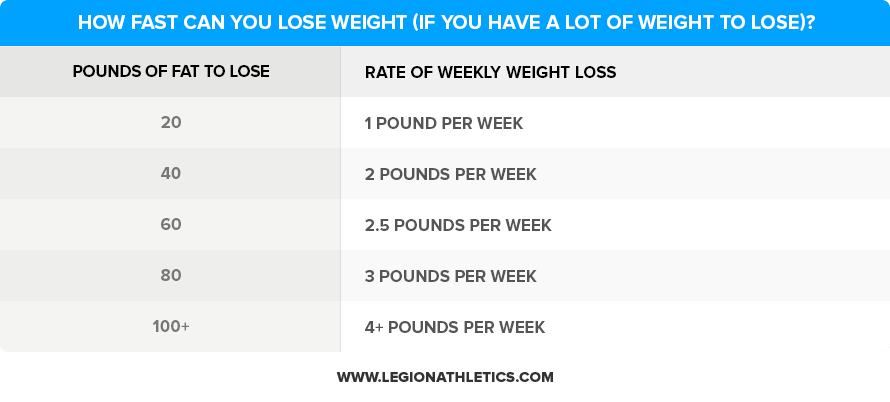

We don’t need to get too snarled in the science here, but if we take the results of this study, mind what we know about how much weight you can lose before you begin losing muscle (which you should avoid), and account for how ineffective crash diets are, here’s a good heuristic:

In other words, if you have 80 pounds to lose, you can aim to lose 1-to-3 pounds per week without adversely affecting your health.

Bear in mind that you’ll need to adjust this target as you get leaner. For example, say you have 80 pounds to lose. You diet for 6 weeks, losing 18 pounds (3 pounds per week).

At this point, you only have about ~60 pounds to lose, and thus you’ll want to reduce your target rate of weight loss to 2.5 pounds per week. You diet for another 8 weeks, losing another 20 pounds (2.5 pounds per week).

Now you only have 40 pounds to lose, so you’ll want to aim for a weekly weight loss of ~2 pounds per week, and so forth.

You’ll also need to learn which foods to eat and how to exercise to lose weight at this rate and remain healthy. And for that, I recommend my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(Or if you aren’t sure if Bigger Leaner Stronger or Thinner Leaner Stronger is right for you, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz to learn the perfect strength training program for you and the Legion Diet Quiz to learn the best diet for your goals.)

One final caveat is that just because you can lose weight this quickly doesn’t mean you should. While it may not be “unsafe,” it requires a lot of discipline and discomfort, which can cause many people to throw in the towel.

If you’d prefer to use a more moderate, sustainable approach, follow the advice in this article:

The Complete Guide to Safely and Healthily Losing Weight Fast

TL;DR: If you’re very overweight, you can safely lose fat twice as fast as most people think.

The best New Year’s resolutions focus on what you want to do, not what you want to avoid.

Source: “A large-scale experiment on New Year’s resolutions: Approach-oriented goals are more successful than avoidance-oriented goals” published on December 9, 2020 in PLos One.

At this time of year, many people resolve to get healthier.

Some say they’ll take up exercise.

Others that they’ll lose weight.

And still others commit to giving up certain “unhealthy” foods.

However, many of these resolutions go unfulfilled.

Is there anything you can do to increase your chances of succeeding with a New Year’s resolution?

This is the question scientists at Stockholm University sought to answer with this study.

In late December 2016, they split 1,066 people into 3 groups and sent everyone different information about New Year’s resolutions depending on which group they were in.

The first group (“no-support” group) received general information about New Year’s resolutions. At the end of January, June, and December of 2017, the resolvers in this group reported how successful they thought they’d been at achieving their resolutions.

The second group (“some-support” group) received the same information and followed the same procedure as the no-support group. They also received additional information about strategies that make achieving your goals easier and had monthly follow-ups with the researchers throughout 2017.

The third group (“extended-support” group) received the same information and followed the same procedure as the some-support group. In addition, they received information about how to set SMART goals, stay motivated, and deal with setbacks.

Finally, the researchers instructed the resolvers in this group to frame their resolutions as “approach” rather than “avoidance” goals (“I’m going to eat more vegetables” rather than “I’m going to cut out sugar,” for example), and to set small, interim goals throughout the year that would keep them on track to achieve their bigger goals.

The most surprising result was that the resolvers in the some-support group were more likely to be successful (~63%) than those in the no-support (~56%) and extended-support (~53%) groups. In other words, the people receiving the most support were the least successful.

There are a couple of explanations for why this might be.

First, all the data collected was self-reported and subjective. That is, the results don’t actually show that 63% of the people in the some-support group reached their goal; they show that 63% of the people felt they were successful.

Unlike the resolvers in the no-support and some-support groups, the people in the extended-support group were encouraged to use the SMART framework to set very specific goals and track their progress using interim goals throughout the year.

It’s possible, then, that the resolvers in the no-support and some-support groups set vague goals and couldn’t precisely measure their success, leading them to report their progress more positively than those who could objectively see every slip-up.

Second, while the SMART framework can help clarify your goals and may have merit in business, it isn’t a great way to set fitness goals. Thus, it may have been that the resolvers in the extended-support group simply set “bad” goals that they were less likely to achieve.

A second, more workable result was that irrespective of group, people were more likely to be successful if their goal was approach oriented (~59%) rather than avoidance oriented (~47%).

That is, setting goals that outline what you’re going to do rather than what you’re not going to do, makes you significantly more likely to succeed.

To implement this yourself, you may need to “rebrand” some of your current resolutions.

For example, if you’ve committed to eating fewer processed foods, you may want to rework this and focus on eating more whole foods instead. Or, rather than resolving to reduce your time on social media, pledge to do something more productive during downtime, such as exercising, reading, or pursuing a hobby.

TL;DR: Creating approach-oriented (“I will eat more vegetables”) rather than avoidance-oriented New Year’s resolutions (“I’ll eat fewer processed foods”) makes you more likely to achieve your goals.

Scientific References +

- Mcnamara, J. M., & Stearne, D. J. (2010). Flexible nonlinear periodization in a beginner college weight training class. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0B013E3181BC177B

- Graham, T., & Cleather, D. J. (2021). Autoregulation by “Repetitions in Reserve” Leads to Greater Improvements in Strength Over a 12-Week Training Program Than Fixed Loading. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(9), 2451–2456. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003164

- Pareja-Blanco, F., Rodríguez-Rosell, D., Sánchez-Medina, L., Sanchis-Moysi, J., Dorado, C., Mora-Custodio, R., Yáñez-García, J. M., Morales-Alamo, D., Pérez-Suárez, I., Calbet, J. A. L., & González-Badillo, J. J. (2017). Effects of velocity loss during resistance training on athletic performance, strength gains and muscle adaptations. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 27(7), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.12678

- Shattock, K., & Tee, J. C. (2022). Autoregulation in Resistance Training: A Comparison of Subjective Versus Objective Methods. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(3), 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003530

- Colquhoun, R. J., Gai, C. M., Walters, J., Brannon, A. R., Kilpatrick, M. W., D’Agostino, D. P., & Campbell, W. I. (2017). Comparison of Powerlifting Performance in Trained Men Using Traditional and Flexible Daily Undulating Periodization. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001500

- Henselmans, M., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2014). The effect of inter-set rest intervals on resistance exercise-induced muscle hypertrophy. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 44(12), 1635–1643. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40279-014-0228-0

- Behenck, C., Sant’ana, H., Pinto De Castro, J. B., Willardson, J. M., & Miranda, H. (2022). The Effect of Different Rest Intervals Between Agonist-Antagonist Paired Sets on Training Performance and Efficiency. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(3), 781–786. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003648

- Calbet, J. A. L., Ponce-González, J. G., Pérez-Suárez, I., de la Calle Herrero, J., & Holmberg, H. C. (2015). A time-efficient reduction of fat mass in 4 days with exercise and caloric restriction. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 25(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/SMS.12194

- Alpert, S. S. (2005). A limit on the energy transfer rate from the human fat store in hypophagia. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 233(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JTBI.2004.08.029

- Dulloo, A. G., Jacquet, J., & Girardier, L. (1997). Poststarvation hyperphagia and body fat overshooting in humans: a role for feedback signals from lean and fat tissues. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65(3), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1093/AJCN/65.3.717

- Oscarsson, M., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., & Rozental, A. (2020). A large-scale experiment on New Year’s resolutions: Approach-oriented goals are more successful than avoidance-oriented goals. PLoS ONE, 15(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0234097