Key Takeaways

- Shoulder pain is poorly understood, and many of the things that people think help either aren’t scientifically supported or have been debunked.

- Unless you’ve damaged your shoulder in some kind of accident, then the most likely cause of shoulder pain is overuse—doing too much with too little rest.

- The only reliable way to reduce shoulder pain is to rest your shoulder until you’re completely pain free, although there are six other strategies that may help as well.

It’s bench day, and you’ve just loaded the bar with enough weight to set a new PR.

You unrack the bar, lower it to your chest, and right at the bottom a sharp pain shoots through your shoulder. It only lasts for a moment before you slam the bar back onto the rack, so you shrug it off and keep going.

The same thing happens a week later, though, and this time the pain gets progressively worse with each set.

You’ve had aches and pains before, but this is different.

Weeks go by, and now your shoulder hurts when you type, hold a steering wheel, brush your teeth, or do just about anything with your gimpy arm.

It hurts just enough to keep you from making any progress in the gym, but not enough for you to stop lifting entirely.

When you ask your friends what to do, everyone has a different opinion.

“Oh, I had that same thing. You need to try acupuncture.”

“You need to take this supplement—nothing else worked until I tried this.”

“I hate to break it to you, but you’re going to need surgery. That’s just the way it goes, getting old sucks, huh?”

When you turn to the Internet for answers, you run into the same problem.

Everyone has a different opinion about what’s causing your shoulder pain, how long it will take to heal, and how to fix it.

Some say that shoulder pain is caused by poor posture, muscle imbalances, lack of flexibility, overtraining, or any kind of heavy weightlifting, but no one can really explain why.

Finding solutions is even more of a crapshoot. Here’s just a shortlist of the things people say you should try:

- Stretching

- Massage

- Chiropractic

- Foam rolling

- Acupuncture

- Prolotherapy injections

- Posture correction

- NSAIDs

- Glucosamine chondroitin

- Ice

- Physical therapy

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

- Corticosteroid injections

. . . and more.

There’s a reason everyone seems to have an opinion. Over the course of a year, anywhere from 7 to 67% of people have some form of shoulder pain, and that number is even higher in athletes.

So, how are you supposed to know who’s right?

Well, the short story is this:

Shoulder pain is a poorly understood phenomenon, and outside of a few rare cases, it’s almost impossible to tell exactly what’s causing it. The good news, though, is that most forms of shoulder pain resolve by themselves if you rest properly (and that’s not as simple as just staying out of the gym).

In this article, you’ll learn what causes shoulder pain, what does and doesn’t work for reducing shoulder pain, and the seven best ways to fix shoulder pain for good.

Let’s get started.

What Causes Shoulder Pain?

One of the reasons shoulder pain tends to be so frustrating is that it’s rarely obvious what’s causing it.

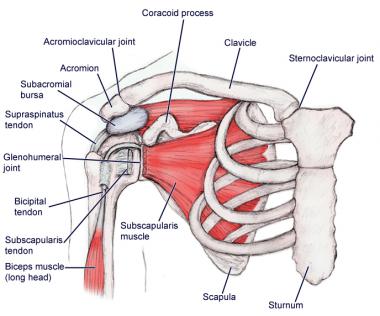

Unlike a simple hinge joint, like the knee, the shoulder joint is made up of many different bones, tendons, muscles, ligaments, and other structures that intersect in a jumbled mess, making it hard to tell what might be hurting and why.

Here’s what it looks like:

This is why some people say that the shoulder joint is actually four different joints in one:

The glenohumeral joint, where the humerus meets the scapula.

The acromioclavicular joint, where the clavicle meets the scapula.

The sternoclavicular joint, where the clavicle meets the sternum.

The scapulothoracic joint, where the scapula connects to your ribs.

Muscles from your arm, chest, back, and neck all crisscross the area, and there are several large bursa, or fluid-filled sacs that pad your joints, stuck in there too.

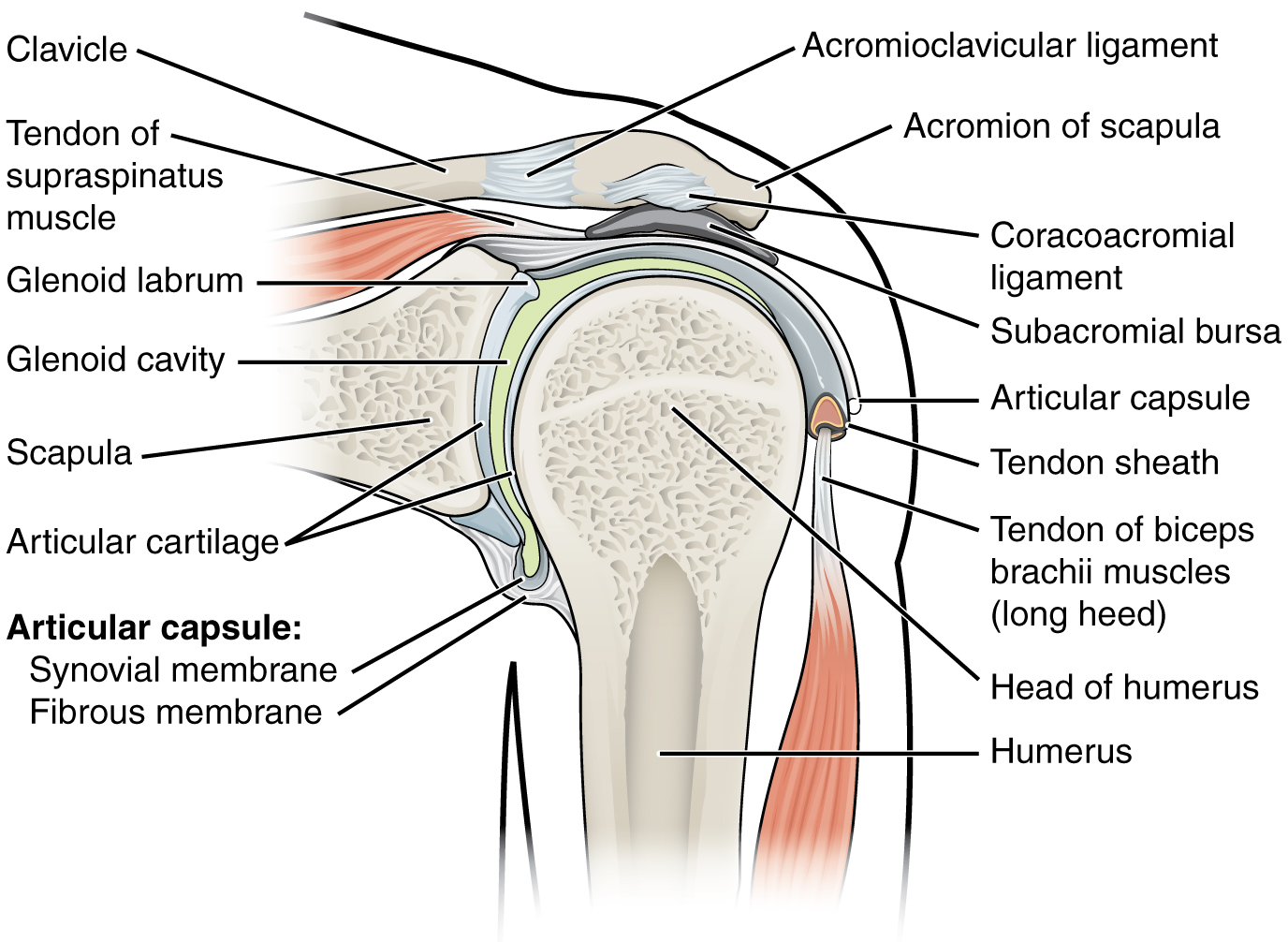

Here’s what all these structures look like up close:

This is why it’s so hard to get a straight answer when figuring out what’s causing your shoulder pain.

Here’s a shortlist of potential culprits:

- Tendinitis

- Tendinosis

- Bursitis

- Rotator cuff strain or tear

- Frozen shoulder

- Arthritis

- Calcific tendonitis

- Shoulder dislocation

- Shoulder separation

- Labral tear

- Biceps tendonitis or tendinosis

- Trauma

We don’t need to get into each of these problems, because all of them can be lumped into one of three categories:

- Repetitive strain injuries (RSIs)

- Traumatic injuries.

- Chronic injuries.

Let’s look at each.

1. Repetitive strain injuries (RSIs).

Repetitive strain injuries are caused by the wear and tear from repeated movement and overuse.

RSIs tend to start small and get progressively worse over time, which is why many people keep training and make the problem much worse.

RSIs are one of the most common causes of shoulder pain in athletes.

2. Traumatic injuries.

Traumatic injuries are injuries caused by an immediate tear, strain, or bruise.

When it comes to shoulder pain, this would be something like letting a dumbbell rip your arm back when chest pressing or dropping a barbell on your chest when benching.

Luckily, these kinds of injuries are relatively rare. When they do happen, they’re usually painful enough that people have the common sense not to keep training, too.

3. Chronic injuries.

Chronic injuries are any kind of repetitive strain or traumatic injury that should have healed, but hasn’t.

In most cases, these kinds of injuries only bother you off and on, and while they’re painful enough to be annoying, they aren’t bothersome enough to make you stay out of the gym.

Chronic injuries can be caused by any number of things, but as you’ll see, they’re typically related to overuse.

By far the most common of these three injuries is the repetitive strain injury.

That doesn’t tell us what’s hurting, why it’s hurting, or what to do about it, though.

And unfortunately, it’s impossible to find definitive answers to those questions.

Muscle pain and tightness are rather mysterious phenomena, and many of things that have long been assumed to produce them have been debunked.

For instance, many people think that any kind of shoulder pain must be caused by inflammation of the muscle, bursa, or tendon (such as tendonitis) but the truth is that many shoulder injuries aren’t inflamed.

Instead, there are tiny microtears in the joint structures that your body hasn’t been able to repair as fast as you’ve been creating them, which compromises the strength of those tissues (this is known as tendinosis).

This is why physical therapists often give people several different treatments, in the hopes that one or some of them will work. As unscientific as it sounds, reducing pain is often a matter of throwing a bunch of things at the wall and seeing what sticks.

That said, you still want to focus on the solutions that are most likely to work, so let’s look at some of the most common techniques people use to fix shoulder pain and see how they stack up.

What’s the Best Way to Reduce Shoulder Pain?

Here’s the bad news: There’s very little research on the best ways to reduce shoulder pain, specifically.

The good news?

There’s a lot of data on pain and joint pain in general, and it’s fair to assume that most of that applies to shoulder pain, too.

With that in mind, let’s look at 15 of the best and worst cures for shoulder pain, and see how they stack up against the evidence.

Shoulder Pain and Stretching

The idea that stretching reduces pain goes something like this:

- “Tightness” and lack of flexibility can cause and exacerbate injuries, so becoming more flexible reduces pain and helps you heal faster.

- Stretching makes you more flexible, so stretching helps fix your shoulder pain.

That sounds good in theory, but it fails at almost every level.

First of all, there’s no link between shoulder flexibility and range of motion and shoulder pain. In other words, people who are less flexible aren’t necessarily more likely to experience shoulder pain.

Second, there’s very little evidence that stretching reduces pain or soreness. Some research shows stretching might help reduce pain, but the effects are so small that they aren’t much different from doing nothing.

Another study found that active release technique (ART), a specific kind of stretching, helped reduce neck pain, but the improvements were miniscule.

That said, stretching could reduce inflammation in connective tissue, and inflammation could be one contributor to joint pain. Right now, though, no one knows for sure. If inflammation isn’t the cause of your shoulder pain, then it’s even less likely this would help.

The bottom line is that stretching might help reduce shoulder pain a little in the short term, but there’s no evidence becoming more flexible will help prevent shoulder pain or reduce shoulder pain in the long term.

Shoulder Pain and Massage

Massage feels good, has very few risks, and is used by many people to reduce pain, but how well does it really work?

Research goes back and forth. Some studies show massage reduces joint pain and others don’t, but on the whole it looks like it’s better than doing nothing.

It’s also hard to say if the (small) benefits of massage therapy are due to the massage, or from a more general improvement in mood.

Massage reduces anxiety and depression, which are both linked with joint pain, so it’s possible that simply feeling better is what makes the pain diminish.

The bottom line is that massage may help reduce your shoulder pain and certainly won’t hurt, but it’s far from a sure bet. If you can afford it, it’s probably worth a shot.

Shoulder Pain and Chiropractic

Chiropractic is a form of alternative medicine based on fixing misaligned joints, especially the spine, by manually pushing and pulling them back into position. In theory, realigning joints this way improves the function of nerves, muscles, and other organs in the body.

No studies have directly measured how chiropractic affects shoulder pain, but the little evidence available doesn’t look good.

Most studies show chiropractic doesn’t reduce joint pain, and the few that do also show that it’s not any more effective than other kinds of therapy.

There isn’t even a plausible mechanism for how chiropractic could help reduce shoulder pain.

To be fair, many people say that chiropractic helps them feel better, and there’s truth to the idea that, “If it works, it works.” On the other hand, chances are good that any improvement is more likely a placebo effect, so don’t count on chiropractic to actually fix whatever is wrong with your shoulder.

The bottom line is that there’s little evidence that chiropractic will reduce shoulder pain, and if it does help you feel better, chances are good it was through a placebo effect.

Shoulder Pain and Foam Rolling

Foam rolling is a kind of self-massage that involves using a foam tube to rub and compress muscles.

Depending on who you ask, one of the main arguments for foam rolling is the idea that pain is caused by trigger points—patches of connective tissue that become overstimulated, tight, and painful. This connective tissue is known as fascia, and it attaches, protects, and separates muscles and other internal organs.

In theory, kneading these trigger points with a foam roller, tennis ball, or a stick helps release these tight patches of fascia, thus reducing pain.

There are several parts of this theory that don’t add up, though:

- The parts of a muscle that feel the tightest and most painful are, objectively, often the softest parts of the muscle. That’s the opposite of what you’d expect if “tight” fascia were causing pain.

- Trigger point experts often can’t agree what the different trigger points are or how to find them, so it’s hard to say that foam rolling them is a reliable way to reduce pain.

- Studies on trigger point therapy are all over the place. Some show that it helps reduce pain and others don’t, and none of the results are impressive.

All in all, the evidence for foam rolling is probably one rung down from getting a professional massage. It’s probably better than doing nothing, but not much.

The bottom line is that there’s almost no evidence that foam rolling reduces shoulder pain, but it’s probably better than nothing if it makes you feel better.

Shoulder Pain and Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a kind of alternative medicine that involves poking the skin or tissues with extremely thin needles to alleviate pain and to treat various physical, mental, and emotional problems.

Some people say acupuncture works because it “define rebala” the lifeforce of your body, which they call“qi.” Others say it works because it stimulates the body to produce more painkilling chemicals. And others don’t really try to justify why it works.

What do studies show, though?

Well, that acupuncture doesn’t work.

People who get acupuncture for shoulder pain get about the same results as people who get a placebo treatment. About the best you can expect is a short drop in pain for a few weeks, and even then, the results are so small that they’re almost nonexistent in most cases.

Another problem is that most of the studies on acupuncture are riddled with flaws:

- First, most of the studies are poorly blinded, which means it’s too obvious to either the researchers or the subjects who’s receiving the treatment (and this can skew the results in favor of acupuncture).

- Second, when you’re dealing with pain, providing just about any type of treatment is better than simply doing nothing (thanks to the placebo effect).

- Third, the few positive results are disappointingly small. For example, people who get acupuncture for knee pain typically say their pain improves by 4 points on a 20 point scale, and people who get a placebo treatment say their pain improves by 3 points on a 20 point scale. Not exactly impressive.

The bottom line is that there’s very little evidence that acupuncture can reduce shoulder pain, and in most cases, it’s no better than doing nothing.

Shoulder Pain and Weight Loss

There’s evidence that weight gain may be partly responsible for one of the most common kinds of shoulder pain, known as adhesive capsulitis, or “frozen shoulder.”

Researchers aren’t entirely sure why, but it could have something to do with weight gain increasing whole-body inflammation.

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is linked with a number of aches and pains, and it may also increase your risk of shoulder pain.

This hasn’t been proven outright, but it seems possible.

The bottom line is that losing weight may reduce your risk of shoulder pain, and if nothing else, we know it’s going to improve your health overall.

Shoulder Pain and Posture

If you’ve ever visited a physical therapist, chances are they’ve told you that the reason your shoulder hurts is due to poor posture or “misalignment.”

The general idea is that small quirks in your posture, like putting more weight on one leg when you stand, gradually pull your body out of alignment. This forces other parts of your body compensate by altering their movement, which leads to pain over time.

If you fix your posture, it’s claimed, then everything will fall back into alignment and the pain will go away.

And all of this is more or less hogwash.

There’s very little evidence that small irregularities in posture, movement, or alignment increase your risk of any kind of joint pain.

This idea has been thoroughly debunked for shoulder pain, neck pain, knee pain, back pain, and many other kinds of joint pain.

One of the main nails in the coffin for this idea is evidence that people experience pain with no signs of physical injury or “misalignment,” and there are other cases where people have serious structural damage like dislocated vertebrae, but no pain.

Other studies have shown that muscle imbalances and variations in posture aren’t linked with joint pain.

This isn’t to say that poor posture couldn’t have any effect on shoulder pain, but it’s rarely the main cause.

The bottom line is that poor posture is almost certainly not the main cause of your shoulder pain, and “posture correcting” exercises have never been proven to reduce shoulder pain.

Shoulder Pain and NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) are drugs that block chemicals made by your body that increase pain, swelling, and inflammation.

Some of the most common NSAIDs are ibuprofen (Advil), naproxen (Aleve), and celecoxib (Celebrex).

There are two main reasons people take NSAIDs for joint pain:

- To reduce pain in the short term.

- To reduce inflammation, which is sometimes associated with joint pain.

In the short term, NSAIDs can reduce pain, which is why they aren’t a bad choice if you’re only taking them for a few days to get through the worst of the pain.

If your shoulder pain is caused by inflammation, then NSAIDs may also be able to help fix the actual cause of your pain, and not just reduce pain.

Unfortunately, many shoulder injuries aren’t inflamed, which means painkillers like NSAIDs aren’t actually healing your shoulder. This is why most NSAIDs don’t work well for reducing joint pain for more than a few days or weeks.

So, if it just makes your shoulder feel better, what’s the problem with taking them?

Well, there are a few risks with NSAIDs, too.

First, gastrointestinal problems like ulcers have been noted with long-term NSAID use. This doesn’t happen often, but it’s possible.

Second, if you mask the pain with NSAIDs, it’s easier to re-injure your shoulder by training harder than you otherwise would.

That said, assuming you’re otherwise healthy, there’s no reason you can’t take NSAIDs for a few days to get through the worst of the pain if you injure your shoulder.

The bottom line is that NSAIDs can reduce pain for a few days or weeks, but they don’t work well for healing shoulder injuries or reducing pain long term. If you take them to cover up shoulder pain so you can keep training, chances are good you’ll only re-injure your shoulder.

Shoulder Pain and Glucosamine Chondroitin

Glucosamine and chondroitin are structural components of collagen, the main protein that forms cartilage.

Both compounds are produced naturally by the body, but they’re also sold together as the supplement glucosamine-chondroitin. The idea is that by providing the body with more of these two chemicals, you can improve joint health.

It hasn’t panned out that way, though.

There’s no evidence that joint pain is caused by a lack of glucosamine and chondroitin, so it doesn’t make sense that supplementing with these compounds would reduce joint pain.

Additionally, studies have repeatedly shown that glucosamine-chondroitin isn’t effective for reducing joint pain or improving cartilage health.

It flat out doesn’t work.

The bottom line is that glucosamine-chondroitin supplements have never been proven to reduce or prevent joint pain.

Shoulder Pain and Icing

The idea behind icing goes like this:

- Inflammation causes pain and makes it harder for injuries to heal.

- Reducing inflammation will reduce pain and help injuries heal faster.

- Icing reduces inflammation.

- Therefore, icing reduces pain and helps you heal faster.

This logic has made icing standard dogma for decades—if any joint hurts, you should ice it early and often.

Recently, though, the pendulum has swung in the other direction. Now, experts warn that icing can actually slow healing and prolong joint pain.

The good news is that both groups are wrong.

There’s very little evidence that icing helps, hurts, or does anything to your joints.

The same thing is true of alternating between icing and warming, known as “contrast therapy,” it doesn’t seem to do much of anything.

That said, icing can reduce joint pain for as long as you keep the cold pack on your shoulder, but it’s not going to make shoulder pain go away faster over the long term.

The bottom line is that icing has never been proven to reduce joint pain, but it can temporarily reduce your shoulder pain by numbing the area.

Shoulder Pain and Physical Therapy

Physical therapy, also called physiotherapy (PT), involves using exercises, special devices, and education to help people regain or preserve healthy movement.

PT can involve any number of different treatments from massage to special movement exercises to medical devices that reinforce proper movement. Different physical therapists also have different methods and recommend different techniques, so it’s hard to say across the board whether it “works” or not.

When it comes to shoulder pain, studies are hit and miss. Some show it helps, others don’t, and many of them are too small or low quality to tell either way.

Interestingly, one thing we do know is that the people who are happiest with their physical therapist generally have the best results. Whether that’s because simply feeling like you’re in the hands of a trained, kind professional reduces pain, or whether these people liked their therapist more because they did a great job, is impossible to say.

What we can say, is that if you decide to see a physical therapist, make sure it’s someone you like.

The bottom line is that physical therapy might help reduce shoulder pain, but that depends on what’s causing the pain and what the therapist recommends.

Shoulder Pain and Prolotherapy

Prolotherapy, or “proliferation therapy,” involves injecting an irritant into a tendon, muscle, or joint to promote the growth of new tissue.

Typically, either a sugar solution (dextrose) or a purified form of cod liver oil (morrhuate sodium) is injected every few weeks for several months. The idea is that by irritating the surrounding tissue, you can encourage the body to heal itself.

Researchers have tested prolotherapy on all kinds of muscle and joint pain, including . . .

. . . and the best we can really say is that it might help reduce pain for some problems, but most of the time it either doesn’t work or the benefits are too small to matter.

The underlying mechanism for why prolotherapy might work has also never been proven, and studies show that there’s no increase in cartilage growth after prolotherapy injections.

The bottom line is that prolotherapy probably doesn’t reduce shoulder pain, and almost certainly isn’t worth the cost, inconvenience, and discomfort of having to get repeated injections.

Shoulder Pain and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) involves using a device to send an electric current through the skin to stimulate nerves and reduce pain.

Sending an electric current through the skin can cause some odd sensations and muscle contractions that could “drown out” pain, and it may be able to suppress pain signals in the brain, but that doesn’t necessarily fix the underlying problem.

One review study on TENS found that it helps about half the time and doesn’t help the other half. Other studies are even less positive, and show it probably just doesn’t work for joint pain (although it might help other conditions, like diabetic neuropathy).

The bottom line is that TENS might help reduce some kinds of pain, but it probably won’t work for shoulder pain.

Shoulder Pain and Corticosteroid Injections

Cortisone is a kind of steroid that reduces inflammation. A corticosteroid injection, or cortisone shot, is an injection of cortisone into a tendon to reduce inflammation and pain.

They’re often used for joint pain such as carpal tunnel syndrome, knee pain, and shoulder pain.

Cortisone shots can reduce inflammation and shoulder pain in the short term, but as soon as the drugs start to wear off, the pain returns.

Some researchers also think there’s a link between cortisone shots and tendon degeneration, although that’s still largely unproven.

The bottom line is that, in most cases, cortisone shots aren’t going to reduce your shoulder pain for long, and won’t do anything to heal your shoulder.

Shoulder Pain and Rest

Some people say that as soon as your shoulder starts hurting, you should stop working out completely and rest as long as you need to before you do any kind of exercise.

There’s some truth to that. Most people have a tendency to “push through the pain,” which only makes the problem worse.

But you don’t want to stop working out entirely.

In general, complete rest actually increases pain or delays healing compared to light activity. Other research on both repetitive strain injuries and traumatic injuries shows that light exercise helps connective tissue heal faster.

So, while you don’t want to keep doing any activities that cause pain, you want to stay as active as you can without causing your shoulder to hurt any more than it already does.

I saved this for last because, right now, active rest is about the most well-supported treatment for shoulder pain out there. If moving your shoulder in a particular way hurts, then stop moving your shoulder that way until it’s back to 100 percent.

The bottom line is that active rest—moving your shoulder as much as possible without experiencing any pain—is the most reliable way to reduce shoulder pain.

7 Ways to Reduce and Prevent Shoulder Pain

At this point you’re probably thinking, “Great, so what the hell am I supposed to do about my shoulder?”

Well, that’s what you’re about to learn.

There are seven things you can do that will reduce shoulder pain in most cases. None of them are guaranteed fixes, but they’re your best options.

The first technique is by far the most reliable. After that, the remaining six fall into the category of “throw it at the wall and see what sticks.” They might help, but they’re also unlikely to hurt, so there’s no harm in trying them.

Shoulder Pain Solution #1

Stop Doing Whatever Makes Your Shoulder Hurt

If your shoulder hurts during certain exercises, and you haven’t been through some traumatic injury, then chances are good you’re dealing with some kind of repetitive strain injury (RSI).

To understand why, we need to look at what happens to your body when you exercise in the first place.

When you lift weights, the tissues in your muscles, tendons, and joints sustain small amounts of damage. Between workouts, your body repairs as much of the wear and tear as it can and, provided you allow enough time for recovery, these tissues get stronger and more durable over time.

Sometimes, though, this wear and tear builds up faster than your body can repair it, and things start hurting.

As mentioned earlier, the single biggest mistake people make when dealing with repetitive stress injuries is they ignore the early warning signs and keep training as normal. Sometimes the pain goes away on its own, but most of the time, you’re just digging yourself into a deeper and deeper hole.

This is how a minor, niggling pain can grow into a debilitating injury that takes months to heal.

Luckily, the solution is simple—rest.

Assuming you just have an RSI, and you’re otherwise healthy, your body shouldn’t have any trouble repairing itself.

Now, the annoying part is that some injuries can take a while to heal, which means taking weeks or even months away from the activity that caused the injury.

Tendon injuries are one of the most frustrating, as they typically take much longer to heal than other kinds of damage.

The good news is that you don’t have to stop exercising altogether. Studies show that active rest, doing light activity but avoiding anything that causes pain, can help you heal faster.

So, as a general rule, the best way to reduce shoulder pain is to move your shoulder as much as possible without experiencing any pain.

There are two approaches you can take to this:

- Immediately stop lifting weights and start doing other activities, like walking, that don’t hurt your shoulder.

- Modify your lifting plan to work around your shoulder pain.

Both approaches have pros and cons.

If you take the first option, then there’s almost zero chance of prolonging your shoulder pain, but you also have to stop doing any kind of weightlifting.

If your shoulder’s been hurting for a while, this is a better option. The easiest way to practice active rest is to pick a different form of exercise, like walking, cycling, rowing, hiking, or swimming, and start doing that for at least 30 minutes a day.

If you take the second option, then it might take longer to recover, but you also get to keep going to the gym.

If your shoulder doesn’t hurt much, hasn’t been hurting for long, or only hurts when you do certain exercises, this might be the better option.

Let’s say your shoulder hurts when you bench. Here’s how you might go about modifying your plan, starting with the first option and working your way down the list until the pain goes away:

- Use different variations of bench press that don’t hurt, such as dumbbell press, machine bench, spoto press, or close-grip bench.

- Stop doing all pushing exercises.

- Stop doing all upper body exercises.

- Stop lifting until you feel better.

If you’re looking for a simple exercise plan that you can do while you let your shoulder heal, check out this article:

Shoulder Pain Solution #2

Improve Your Shoulder Mobility

As we covered earlier, there isn’t much evidence that stretching, foam rolling, or mobility exercises prevent or reduce shoulder pain, but they aren’t going to hurt, either, and many people find these strategies help them feel better.

Mobility refers to how well you can move a joint through its natural range of motion.

When it comes to the shoulder, this means being able to move your arms without feelings of tightness when doing exercises like the bench press, overhead press, and incline bench press.

Most shoulder mobility exercises involve using simple stretches or tools like foam rollers, elastic bands, and lacrosse balls to massage and stretch the muscles around your shoulders, neck, and chest.

If you want to learn more about how to increase your shoulder mobility, then check out this article:

Shoulder Pain Solution #3

Increase Your Shoulder Strength

If you aren’t currently lifting weights, and doing so doesn’t hurt your shoulder, then you should start.

Increasing shoulder strength is one of the more reliable ways to avoid shoulder pain, and the same thing is true of neck pain as well.

You don’t need to do special physical therapy exercises either. The study listed above used simple dumbbell exercises like the dumbbell row, dumbbell shrug, and lateral raise.

If you’d like to learn how to increase your shoulder strength, check out this article:

The Ultimate Shoulder Workout: The Best Shoulder Exercises for Big Delts

Shoulder Pain Solution #4

Use Proper Form In Your Weightlifting

Weightlifting injuries are less common than most people think, but when they do happen, it’s often because the person wasn’t using proper technique.

Form mistakes go far beyond the heavy half repping that gives a bad name to the big compound lifts like the squat, deadlift, bench press, and military press. You can work with proper amounts of weight and use a full range of motion and still put yourself at a considerable risk of injury.

For instance…

- If you round your back during a deadlift, or hyperextend it too far at the top, you’re asking for a lower back injury.

- If you flatten your back and round your shoulders at the top of a bench press, or flare your elbows out too much, you’ll probably have shoulder problems at some point.

- If you let your knees bow in when you squat, you can really hurt them when going heavy.

Most exercises have little quirks like these, which is why you should take the time to learn proper form on everything you’re doing, and make sure to stick to it.

Bodybuilding.com’s videos are a great resource for this, and you may also like the following articles on how to do some of the most important lifts:

The Deadlift and Your Lower Back: Harmful or Helpful?

Squatting and Your Knees and Back: Injury Risk or Safe?

The Ultimate Guide to the Military Press: The Key to Great Shoulders

Shoulder Pain Solution #5

Warm Up Properly

Many people’s warm-up routines consist of a few minutes of static stretching.

This is a bad way to go about it.

Static stretching before exercise has been shown to impair speed and strength, and not only fail to help prevent injury, but possibly increase risk of injury due to the cellular damage it causes to muscle and its analgesic effect.

A proper warm-up routine should increase blood flow to the muscles that are about to be trained, increase suppleness, raise body temperature, and enhance free, coordinated movement.

The best way to do this is to move the muscles repeatedly through the expected ranges of motion, which does reduce the risk of injury.

That’s why it’s best to stick to a simple, short, multi-set warm-up routine like the one you’ll find in the books Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger, that goes like this:

First Warm-Up Set

8 reps with 50% of your working set weight

Rest 1 minute

Second Warm-Up Set

6 reps with 50% of your working set weight

Rest 1 minute

Third Warm-Up Set

4 reps with 70% of your working set weight

Rest 1 minute

Fourth Warm-Up Set

1 rep with 90% of your working set weight

Rest 2 minutes and then start your workout

By doing this warm-up routine, you’ll not only help prevent injury, but you’ll probably find that you can lift more weight while maintaining proper form.

Shoulder Pain Solution #6

Massage Your Shoulder

Massage is one of the safest, least invasive things you can do to reduce shoulder pain.

There isn’t much evidence for or against it, but many people find it helps reduce pain at least for a while.

It might help, and probably won’t hurt, so it’s worth a shot if you can afford it.

Shoulder Pain Solution #7

Take the Right Supplements

Compared to active rest and following a proper workout routine, supplements are going to have a very, very small impact on how fast you heal from shoulder pain.

Some of the most popular supplements for joint pain, like glucosamine-chondroitin, have also been thoroughly debunked.

That said, there are safe, natural substances that science indicates may help prevent and reduce shoulder pain. (And if you’d like to know exactly what supplements to take to keep you healthy, injury-free, and full of vitality take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz.)

Let’s quickly review the supplements that are most likely to help.

Fish Oil

Fish oil is known for being anti-inflammatory, and in cases where shoulder pain is caused by inflammation, taking fish oil may help.

The two main ingredients in fish oil, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), improve the production of anti-inflammatory compounds in the body.

If you eat several servings of fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, sardines, and cod every week, you may not benefit from supplementation with fish oil. If you don’t, however, it’s a good idea to include it in your daily supplement regimen.

And if you’re looking for a high-quality fish oil, then you want to check out Triton.

It’s a high-potency, 100% triglyceride fish oil with added vitamin E to prevent oxidation and rancidity, and natural lemon oil, which prevents noxious “fish oil burps.”

Furthermore, it’s made from sustainably fished deep-water anchovies and sardines and is molecularly distilled to remove synthetic and natural toxins and contaminants.

So, if you want to optimize your mental and physical health and performance and reduce the risk of disease and dysfunction, like shoulder pain, then you want to try Triton today.

Curcumin

Curcumin is the yellow pigment found in the turmeric plant, which is the main spice in curry. It’s been used therapeutically in Ayurvedic medicine for thousands of years.

Its health benefits are extensive, and scientific researchers around the world are investigating applications for fighting a variety of diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and more.

One reason for this is that curcumin has powerful anti-inflammatory effects, which are exerted by inhibiting proteins that trigger the production of inflammatory chemicals.

Curcumin has a significant downside, however: intestinal absorption is very poor. So much so that supplementation without enhancement more or less eliminates the majority of its health benefits.

Fortunately, there’s an easy solution for increasing bioavailability: black pepper extract.

Research shows that pairing black pepper extract with curcumin increases bioavailability twentyfold. And when you do that, curcumin becomes an effective joint support supplement.

Studies show that supplementation with curcumin and black pepper extract reduces inflammatory signals in the joints and, in those with arthritis, relieves pain and stiffness and improves mobility.

When paired with piperine, the clinically effective dosages of curcumin range between 200 and 500 milligrams.

And that’s why there’s 500 mg of curcumin and 25 mg of piperine in each serving of our joint supplement, FORTIFY.

FORTIFY also contains clinically effective doses of three other ingredients also proven to enhance joint health and function:

- Undenatured type ll collagen

- Boswellia serrata

- Grape seed extract

The bottom line is if you want healthy, functional, and pain-free joints that can withstand the demands of your active lifestyle, then you want to try FORTIFY today.

Undenatured Type ll Collagen

Collagen is the main component of your body’s connective tissues, which means it serves as the primary building block for various things in it, including your skin, teeth, cartilage, bones, and tendons.

The collagen found in supplements comes from the connective tissue in animals, such as cows, chickens, and fish, and while there are over 37 different kinds of collagen in animals, they can be divided into two main categories:

- Type I collagen is the most abundant collagen of the human body, and is present in scar tissue, tendons, ligaments, skin, bones, and more.

- Type II collagen is the collagen that preserves joint function and protects them against damage.

In some cases, your body’s immune system can begin tearing down your own cartilage, in a condition known as arthritis.

Studies show that type II collagen can help alleviate this condition by “teaching” the immune system to stop attacking the proteins in joint cartilage, which in turn can significantly improve joint health and function and decrease or even eliminate pain and swelling.

In other words, type II collagen supplements can work like a natural vaccine of sorts, allowing your body to recognize its own joint collagen as a safe substance, thereby switching off the autoimmune response.

And the best part about type II collagen supplements is that these effects have been demonstrated in people with arthritic conditions and people with healthy joints.

The clinically effective dose of collagen is between 10 to 40 milligrams per day for improving joint health.

That’s a rather large range for dosing, but that’s only because studies have shown benefits using various doses, and it isn’t clear if more is better. Research clearly shows that 10 milligrams is effective, but not that two, three, or four times that amount is necessarily better.

This is why FORTIFY contains a clinically effective dosage of 10 milligrams of undenatured type ll collagen in every serving.

Pycnogenol

Pycnogenol is a compound derived from the bark of the maritime pine tree, or Pinus maritima.

It’s similar to white willow bark in that it works by reducing the production of inflammatory compounds in the body, and it also seems to reliably reduce joint pain.

The clinically effective dosage of pycnogenol is 100 to 200 mg per day.

The downside of pycnogenol is that it’s also expensive, which is why most supplements use a similar compound known as grape seed extract. Both of these compounds contain what are known as procyanidins, which are chains of antioxidants found in some plants. Although they aren’t exactly the same, it’s likely that grape seed extract offers some of the same benefits.

The clinically effective dosage of grape seed extract is 75 to 300 mg per day, which is why FORTIFY contains 90 mg of grape seed extract per serving.

Boswellia serrata

Boswellia serrata is a plant that produces an aromatic substance known as frankinsence, which has been used for thousands of years in Ayurvedic medicine to treat various disorders related to inflammation.

Thanks to modern science, we now know why.

Frankinsence contains molecules known as boswellic acids. Research shows that, like curcumin, boswellic acids—and one in particular known as acetyl-keto-beta-boswellic acid, or AKBA—inhibit the production of several proteins that cause inflammation in the body.

And in case you’re wondering, the difference between the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of curcumin and boswellic acids is they work on different enzymes. Curcumin inhibits an enzyme known as cyclooxygenase, or COX, and boswellic acids inhibit lysyl oxidase, or LOX (and, most notably, 5-LOX).

These anti-inflammatory properties extend to the joints, which is why studies show that Boswellia serrata is an effective treatment for reducing joint inflammation and pain as well as inhibiting the autoimmune response that eats away at joint cartilage and eventually causes arthritis.

The clinically effective dosages of boswellia serrata range between 100 and 200 milligrams.

This is why there is 150 mg of boswellia serrata in each serving of FORTIFY.

White Willow Bark

White willow bark is similar to aspirin (which is a synthetic version of a chemical that’s also found in willow), that’s been used to reduce pain and inflammation for thousands of years.

It works by blocking the production of inflammatory compounds produced in the body, and it works about as well as NSAIDs.

The clinically effective dosage of white willow bark is 240 milligrams per day.

Oh, and if you aren’t sure if the supplements discussed in this article are right for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.

The Bottom Line on Shoulder Pain

Shoulder pain is one of the most common hurdles for us fitness folk.

Unfortunately, most of the things that “everyone knows” help reduce shoulder pain either don’t have any evidence for them or have been debunked.

While it’s impossible to know what causes shoulder pain in every instance, one of the most common culprits is repetitive strain injury, or RSI. These can take anywhere from weeks to months to heal, but you can speed up the process by sticking to the following seven steps:

- Stop doing whatever makes your shoulder hurt.

- Improve your shoulder mobility.

- Increase your shoulder strength.

- Use proper form in your weightlifting.

- Warm up properly.

- Massage your shoulder.

- Take the right supplements.

Do that, and chances are good you’ll be back in the gym in a few weeks.

What’s your take on shoulder pain? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Herman, K., Barton, C., Malliaras, P., & Morrissey, D. (2012). The effectiveness of neuromuscular warm-up strategies, that require no additional equipment, for preventing lower limb injuries during sports participation: a systematic review. BMC Medicine, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-10-75

- McMillian, D. J., Moore, J. H., Hatler, B. S., & Taylor, D. C. (2006). Dynamic vs. static-stretching warm up: The effect on power and agility performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(3), 492–499. https://doi.org/10.1519/18205.1

- Jaeger, M., Freiwald, J., Engelhardt, M., & Lange-Berlin, V. (2003). Differences in hamstring muscle extensibility in elite hockey players and normal participants. Sports Injury – Sports Damage, 17(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-40131

- Macpherson, P. C. D., Schork, M. A., & Faulkner, J. A. (1996). Contraction-induced injury to single fiber segments from fast and slow muscles of rats by single stretches. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology, 271(5 40-5). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.c1438

- Hart, L. (2005). Effect of stretching on sport injury risk: A review. In Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine (Vol. 15, Issue 2, p. 113). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jsm.0000151869.98555.67

- La Torre, A., Castagna, C., Gervasoni, E., Cè, E., Rampichini, S., Ferrarin, M., & Merati, G. (2010). Acute effects of static stretching on squat jump performance at different knee starting angles. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(3), 687–694. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c7b443

- Winchester, J. B., Nelson, A. G., Landin, D., Young, M. A., & Schexnayder, I. C. (2008). Static stretching impairs sprint performance in collegiate track and field athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31815ef202

- Andersen, L. L., Kjær, M., Søgaard, K., Hansen, L., Kryger, A. I., & Sjøgaard, G. (2008). Effect of two contrasting types of physical exercise on chronic neck muscle pain. Arthritis Care and Research, 59(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23256

- Mortensen, P., Larsen, A. I., Zebis, M. K., Pedersen, M. T., Sjøgaard, G., & Andersen, L. L. (2014). Lasting effects of workplace strength training for neck/shoulder/arm pain among laboratory technicians: Natural experiment with 3-year follow-up. BioMed Research International, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/845851

- Macdonald, G. Z., Button, D. C., Drinkwater, E. J., & Behm, D. G. (2014). Foam rolling as a recovery tool after an intense bout of physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46(1), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a123db

- Khan, K. M., Cook, J. L., Taunton, J. E., & Bonar, F. (2000). Overuse tendinosis, not tendinitis. Part 1: A new paradigm for a difficult clinical problem. In Physician and Sportsmedicine (Vol. 28, Issue 5, pp. 38–48). McGraw-Hill Companies. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2000.05.890

- Kjær, M., & Magnusson, S. P. (2008). Mechanical adaptation and tissue remodeling. In Collagen: Structure and Mechanics (pp. 249–267). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73906-9_9

- Mealy, K., Brennan, H., & C Fenelon, G. C. (1986). Early mobilisation of acute whiplash injuries. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 292(6521), 656–657. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.292.6521.656

- Helliwell, P. S., & Taylor, W. J. (2004). Repetitive strain injury. In Postgraduate Medical Journal (Vol. 80, Issue 946, pp. 438–443). The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2003.012591

- Sorrenti, S. J. (2006). Achilles tendon rupture: Effect of early mobilization in rehabilitation after surgical repair. Foot and Ankle International, 27(6), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/107110070602700603

- Hagen, K. B., Jamtvedt, G., Hilde, G., & Winnem, M. F. (2005). The updated cochrane review of bed rest for low back pain and sciatica. In Spine (Vol. 30, Issue 5, pp. 542–546). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000154625.02586.95

- Fisher, P. (2004). Role of Steroids in Tendon Rupture or Disintegration Known for Decades [3]. In Archives of Internal Medicine (Vol. 164, Issue 6, p. 678). American Medical Association. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.6.678-a

- Mohamadi, A., Chan, J. J., Claessen, F. M. A. P., Ring, D., & Chen, N. C. (2017). Corticosteroid Injections Give Small and Transient Pain Relief in Rotator Cuff Tendinosis: A Meta-analysis. In Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (Vol. 475, Issue 1, pp. 232–243). Springer New York LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5002-1

- DeSantana, J. M., Walsh, D. M., Vance, C., Rakel, B. A., & Sluka, K. A. (2008). Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for treatment of hyperalgesia and pain. In Current Rheumatology Reports (Vol. 10, Issue 6, pp. 492–499). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-008-0080-z

- Dubinsky, R. M., & Miyasaki, J. (2010). Assessment: Efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain in neurologic disorders (an evidence-based review): Report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American academy of neurology. Neurology, 74(2), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c918fc

- Haldeman, S., Carroll, L., Cassidy, J. D., Schubert, J., & Nygren, Å. (2008). The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: Executive summary. In Spine (Vol. 33, Issue 4 SUPPL.). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643f40

- Nnoaham, K. E., & Kumbang, J. (2008). Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for chronic pain. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 3). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003222.pub2

- Ellrich, J., & Lamp, S. (2005). Peripheral nerve stimulation inhibits nociceptive processing: An electrophysiological study in healthy volunteers. Neuromodulation, 8(4), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.2005.00029.x

- Rabago, D., Kijowski, R., Woods, M., Patterson, J. J., Mundt, M., Zgierska, A., Grettie, J., Lyftogt, J., & Fortney, L. (2013). Association between disease-specific quality of life and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes in a clinical trial of prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(11), 2075–2082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.025

- Rabago, D., Best, T. M., Beamsley, M., & Patterson, J. (2005). A systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. In Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine (Vol. 15, Issue 5, pp. 376–380). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jsm.0000173268.05318.a4

- Sanderson, L. M., & Bryant, A. (2015). Effectiveness and safety of prolotherapy injections for management of lower limb tendinopathy and fasciopathy: A systematic review. In Journal of Foot and Ankle Research (Vol. 8, Issue 1, p. 57). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-015-0114-5

- Kim, S. R., Stitik, T. P., Foye, P. M., Greenwald, B. D., & Campagnolo, D. I. (2004). Critical Review of Prolotherapy for Osteoarthritis, Low Back Pain and other Musculoskeletal Conditions: A Physiatric Perspective. In American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Vol. 83, Issue 5, pp. 379–389). Am J Phys Med Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHM.0000124443.31707.74

- Staal, J. B., De Bie, R. A., De Vet, H. C. W., Hildebrandt, J., & Nelemans, P. (2009). Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: An updated cochrane review. Spine, 34(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181909558

- Kesikburun, S., Tan, A. K., Yilmaz, B., Yaşar, E., & Yazicioǧlu, K. (2013). Platelet-rich plasma injections in the treatment of chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy: A randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(11), 2609–2615. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546513496542

- Hush, J. M., Cameron, K., & Mackey, M. (2011). Patient Satisfaction With Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy Care: A Systematic Review. Physical Therapy, 91(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100061

- Green, S., Buchbinder, R., & Hetrick, S. E. (2003). Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Vol. 2003, Issue 2). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004258

- Garra, G., Singer, A. J., Leno, R., Taira, B. R., Gupta, N., Mathaikutty, B., & Thode, H. J. (2010). Heat or cold packs for neck and back strain: A randomized controlled trial of efficacy. Academic Emergency Medicine, 17(5), 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00735.x

- Hing, W. A., White, S. G., Bouaaphone, A., & Lee, P. (2008). Contrast therapy-A systematic review. In Physical Therapy in Sport (Vol. 9, Issue 3, pp. 148–161). Phys Ther Sport. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2008.06.001

- Malanga, G. A., Yan, N., & Stark, J. (2015). Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury. In Postgraduate Medicine (Vol. 127, Issue 1, pp. 57–65). Taylor and Francis Inc. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2015.992719

- Collins, N. C. (2008). Is ice right? Does cryotherapy improve outcome for acute soft tissue injury? In Emergency Medicine Journal (Vol. 25, Issue 2, pp. 65–68). Emerg Med J. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2007.051664

- Wandel, S., Jüni, P., Tendal, B., Nüesch, E., Villiger, P. M., Welton, N. J., Reichenbach, S., & Trelle, S. (2010). Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: Network meta-analysis. BMJ (Online), 341(7775), 711. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4675

- Sawitzke, A. D., Shi, H., Finco, M. F., Dunlop, D. D., Harris, C. L., Singer, N. G., Bradley, J. D., Silver, D., Jackson, C. G., Lane, N. E., Oddis, C. V., Wolfe, F., Lisse, J., Furst, D. E., Bingham, C. O., Reda, D. J., Moskowitz, R. W., Williams, H. J., & Clegg, D. O. (2010). Clinical efficacy and safety of glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, their combination, celecoxib or placebo taken to treat osteoarthritis of the knee: 2-Year results from GAIT. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 69(8), 1459–1464. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.120469

- Wilkens, P., Scheel, I. B., Grundnes, O., Hellum, C., & Storheim, K. (2010). Effect of glucosamine on pain-related disability in patients with chronic low back pain and degenerative lumbar osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.893

- Ong, C. K. S., Lirk, P., Tan, C. H., & Seymour, R. A. (2007). An evidence-based update on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In Clinical Medicine and Research (Vol. 5, Issue 1, pp. 19–34). Marshfield Clinic. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2007.698

- Enthoven, W. T. M., Roelofs, P. D. D. M., Deyo, R. A., van Tulder, M. W., & Koes, B. W. (2016). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Vol. 2016, Issue 2). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012087

- Derry, S., Moore, R. A., Gaskell, H., Mcintyre, M., & Wiffen, P. J. (2015). Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Vol. 2017, Issue 3). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3

- Zusman, M. (2011). The Modernisation of Manipulative Therapy. International Journal of Clinical Medicine, 02(05), 644–649. https://doi.org/10.4236/ijcm.2011.25110

- Lun, V., Meeuwisse, W. H., Stergiou, P., & Stefanyshyn, D. (2004). Relation between running injury and static lower limb alignment in recreational runners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(5), 576–580. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2003.005488

- Hides J, F. T., Stanton W, Stanton P, McMahon K, & Wilson S. Psoas. (n.d.). Asymmetry of psoas and quadratus lumborum unrelated to injury. Retrieved November 17, 2020, from https://www.painscience.com/biblio/asymmetry-of-psoas-and-quadratus-lumborum-unrelated-to-injury.html

- S D Boden 1, D O Davis, T S Dina, N J Patronas, & S W Wiesel. (n.d.). Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation - PubMed. Retrieved November 17, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2312537/

- Finan, P. H., Buenaver, L. F., Bounds, S. C., Hussain, S., Park, R. J., Haque, U. J., Campbell, C. M., Haythornthwaite, J. A., Edwards, R. R., & Smith, M. T. (2013). Discordance between pain and radiographic severity in knee osteoarthritis: Findings from quantitative sensory testing of central sensitization. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 65(2), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.34646

- Moseley, G. L. (2012). Teaching people about pain: why do we keep beating around the bush? Pain Management, 2(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.11.73

- Dye, S. F. (2005). The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: A tissue homeostasis perspective. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 436, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000172303.74414.7d

- Grob, D., Frauenfelder, H., & Mannion, A. F. (2007). The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. European Spine Journal, 16(5), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0254-1

- Wright, A. A., Wassinger, C. A., Frank, M., Michener, L. A., & Hegedus, E. J. (2013). Diagnostic accuracy of scapular physical examination tests for shoulder disorders: A systematic review. In British Journal of Sports Medicine (Vol. 47, Issue 14, pp. 886–892). Br J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091573

- Lederman, E. (n.d.). Fall of PSB model in manual and physical therapies.

- Vidal, J. (2002). Updated review on the benefits of weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 26, S25–S28. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802215

- Arendt-Nielsen, L., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & Graven-Nielsen, T. (2011). Basic aspects of musculoskeletal pain: From acute to chronic pain. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 19(4), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1179/106698111X13129729551903

- Pietrzak, M. (2016). Adhesive capsulitis: An age related symptom of metabolic syndrome and chronic low-grade inflammation? Medical Hypotheses, 88, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2016.01.002

- Manheimer, E., Cheng, K., Linde, K., Lao, L., Yoo, J., Wieland, S., van der Windt, D. A., Berman, B. M., & Bouter, L. M. (2010). Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001977.pub2

- Hróbjartsson, A., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (2010). Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Vol. 2010, Issue 1). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3

- Karanicolas, P. J., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2010). Blinding: Who, what, when, why, how? Canadian Journal of Surgery, 53(5), 345–348. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2947122/

- Casimiro, L., Barnsley, L., Brosseau, L., Milne, S., Welch, V., Tugwell, P., & Wells, G. A. (2005). Acupuncture and electroacupuncture for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003788.pub2

- Madsen, M. V., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Hróbjartsson, A. (2009). Acupuncture treatment for pain: Systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups. BMJ (Online), 338(7690), 330–333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a3115

- Rathbone, A. T. L., Grosman-Rimon, L., & Kumbhare, D. A. (2017). Interrater Agreement of Manual Palpation for Identification of Myofascial Trigger Points: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. In Clinical Journal of Pain (Vol. 33, Issue 8, pp. 715–729). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000459

- Ajimsha, M. S., Al-Mudahka, N. R., & Al-Madzhar, J. A. (2015). Effectiveness of myofascial release: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 19(1), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.06.001

- Ge, H. Y., Nie, H., Madeleine, P., Danneskiold-Samsøe, B., Graven-Nielsen, T., & Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2009). Contribution of the local and referred pain from active myofascial trigger points in fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain, 147(1–3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.019

- Andersen, H., Ge, H. Y., Arendt-Nielsen, L., Danneskiold-Samsøe, B., & Graven-Nielsen, T. (2010). Increased Trapezius Pain Sensitivity Is Not Associated With Increased Tissue Hardness. Journal of Pain, 11(5), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.017

- Chaibi, A., Benth, J., Tuchin, P. J., & Russell, M. B. (2017). Chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for migraine: a three-armed, single-blinded, placebo, randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Neurology, 24(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13166

- Mirtz, T. A., Morgan, L., Wyatt, L. H., & Greene, L. (2009). An epidemiological examination of the subluxation construct using Hill’s criteria of causation. In Chiropractic and Osteopathy (Vol. 17, p. 13). BioMed Central. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1340-17-13

- Walker, B. F., French, S. D., Grant, W., & Green, S. (2011). A cochrane review of combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain. In Spine (Vol. 36, Issue 3, pp. 230–242). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318202ac73

- Rubinstein, S. M., Middelkoop, M. van, Assendelft, W. J., Boer, M. R. de, & Tulder, M. W. van. (2011). Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low back pain. In Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin (Vol. 49, Issue 4, p. 41). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd008112.pub2

- Ernst, E., & Canter, P. H. (2006). A systematic review of systematic reviews of spinal manipulation. In Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (Vol. 99, Issue 4, pp. 192–196). Royal Society of Medicine Press. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.99.4.192

- Mok, L. C., & Lee, I. F. K. (2008). Anxiety, depression and pain intensity in patients with low back pain who are admitted to acute care hospitals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(11), 1471–1480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02037.x

- Taylor, A. G., Galper, D. I., Taylor, P., Rice, L. W., Andersen, W., Irvin, W., Wang, X. Q., & Harrell, F. E. (2003). Effects of adjunctive Swedish massage and vibration therapy on short-term postoperative outcomes: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 9(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1089/107555303321222964

- Webb, T. R., & Rajendran, D. (2016). Myofascial techniques: What are their effects on joint range of motion and pain? – A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 20(3), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.02.013

- Langevin, H. M., Stevens-Tuttle, D., Fox, J. R., Badger, G. J., Bouffard, N. A., Krag, M. H., Wu, J., & Henry, S. M. (2009). Ultrasound evidence of altered lumbar connective tissue structure in human subjects with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-151

- Berrueta, L., Muskaj, I., Olenich, S., Butler, T., Badger, G. J., Colas, R. A., Spite, M., Serhan, C. N., & Langevin, H. M. (2016). Stretching Impacts Inflammation Resolution in Connective Tissue. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 231(7), 1621–1627. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25263

- Kim, J. H., Lee, H. S., & Park, S. W. (2015). Effects of the active release technique on pain and range of motion of patients with chronic neck pain. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 27(8), 2461–2464. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.2461

- Sherman, K. J., Cherkin, D. C., Wellman, R. D., Cook, A. J., Hawkes, R. J., Delaney, K., & Deyo, R. A. (2011). A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(22), 2019–2026. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.524

- Sherman, K. J., Cherkin, D. C., Cook, A. J., Hawkes, R. J., Deyo, R. A., Wellman, R., & Khalsa, P. S. (2010). Comparison of yoga versus stretching for chronic low back pain: Protocol for the Yoga Exercise Self-care (YES) trial. Trials, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-11-36

- Herbert, R. D., & Gabriel, M. (2002). Effects of stretching before and after exercising on muscle soreness and risk of injury: Systematic review. In British Medical Journal (Vol. 325, Issue 7362, pp. 468–470). British Medical Journal Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7362.468

- Pope, R. P., Herbert, R. D., Kirwan, J. D., & Graham, B. J. (2000). A randomized trial of preexercise stretching for prevention of lower- limb injury. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32(2), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200002000-00004

- Hill, L., Collins, M., & Posthumus, M. (2015). Risk factors for shoulder pain and injury in swimmers: A critical systematic review. In Physician and Sportsmedicine (Vol. 43, Issue 4, pp. 412–420). Taylor and Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2015.1077097

- Guenther, K. (2016). “It’s All Done with Mirrors”: V.S. Ramachandran and the Material Culture of Phantom Limb Research. In Medical History (Vol. 60, Issue 3, pp. 342–358). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2016.27

- Patel, D. R., Yamasaki, A., & Brown, K. (2017). Epidemiology of sports-related musculoskeletal injuries in young athletes in United States. In Translational Pediatrics (Vol. 6, Issue 3, pp. 160–166). AME Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.21037/tp.2017.04.08

- Lo, Y. P. C., Hsu, Y. C. S., & Chan, K. M. (1990). Epidemiology of shoulder impingement in upper arm sports events. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 24(3), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.24.3.173

- de Oliveira, V. M. A., Pitangui, A. C. R., Gomes, M. R. A., Silva, H. A. d., Passos, M. H. P. do., & de Araújo, R. C. (2017). Shoulder pain in adolescent athletes: prevalence, associated factors and its influence on upper limb function. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 21(2), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2017.03.005

- Luime, J. J., Koes, B. W., Hendriksen, I. J. M., Burdorf, A., Verhagen, A. P., Miedema, H. S., & Verhaar, J. A. N. (2004). Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. In Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology (Vol. 33, Issue 2, pp. 73–81). Scand J Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009740310004667