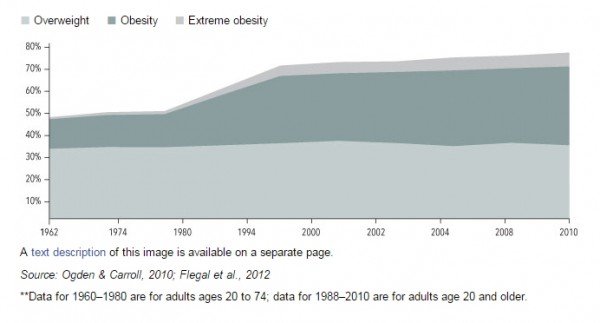

That’s not a pretty graph. It represents untold amounts of frustration, misery, and death–an epidemic of damn near Biblical proportions.

One that’s responsible for 18% of all deaths of adults aged 40 to 85. That’s adding about $190 billion in medical costs every year. That’s robbing the economy of over $160 billion in productivity.

Divine retribution aside, why is it happening, though? Why are so many people so fat, and what can be done about it?

There’s no question that obesity is a complex, multi-faceted issue. Hundreds of billions of dollars have been spent on obesity research over the last several decades, giving thousands of smart scientists the time and resources to explore every nook and cranny of the problem.

And the bigger picture is finally coming into focus.

Fortunately, the 50,000-foot view of obesity is much simpler than many people once believed.Physiologically speaking, the process of becoming and staying obese is fairly easy to understand and, in most cases, fairly straightforward to undo.

It would be impossible to address every nuance of the problem in a blog article, so instead I want to touch on the 7 “guiltiest” culprits–the agents most responsible for our exploding waistlines.

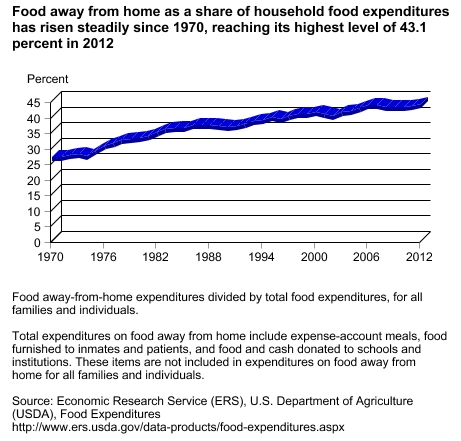

1. We’re eating more food away from home than ever.

Food-away-from-home spending has risen from 25.9% in 1970 to an all-time high of 43.1% in 2012.

In terms of calories, food prepared away from home has increased from 18 to 32% of total daily calories, and as of 2010, fast food accounted for 11.1% of the average adult’s total daily calories.

The problem here?

Food prepared away from home provides more calories per meal than home-prepared foods and is higher in nutrients we overconsume and lower in those we underconsume.

This makes it easier to overeat while also creating or exacerbating micronutrient deficiencies, which not only impairs general health but general satiety as well, which can lead to further overeating.

This problem is particularly relevant to fast food: it’s incredibly calorie dense and nutritionally sparse, which is why research shows that the more someone eats fast food, the fatter they get, and that wherever fast food restaurants go, obesity rates rise.

The Solution

Prepare as much of your daily food at home as possible. This allows you to control your calorie intake and ensure you get the majority of those calories from nutrient-dense foods.

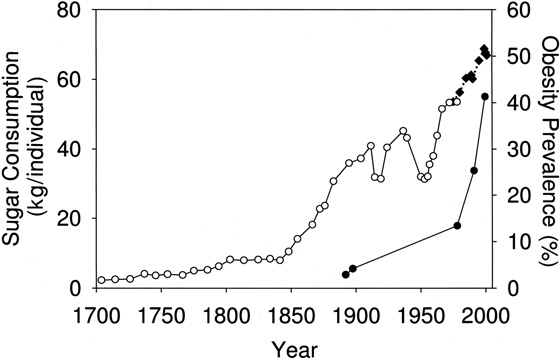

2. We’re eating more sugar than ever.

Anti-sugar hysteria is at an all-time high these days, with many “health experts” denouncing it as destructive to our health as smoking and alcoholism.

Well, the truth is sugar can’t ruin your health unless you eat like an idiot and refuse to exercise…which, unfortunately, describes a large percentage of the population.

You see, long-term consumption of simple sugars like sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup has been associated with an increased risk of heart disease and Type 2 diabetes, but there’s more to consider. Namely, the effects of these sugars varies greatly depending on body composition and activity level.

The leaner and more physically active someone is, the better his body deals with simple sugars; and on the other hand, the more overweight and sedentary someone is, the more harmful high levels of sugar intake becomes.

As far as weight gain goes, we have to remember that both weight gain and loss are regulated by the principles of energy balance, which boils down to this: if you regularly feed your body more energy than it burns, whether from sugar or another form of carbohydrate or protein or dietary fat, you’ll get fatter.

And as a corollary, simply eating sugar can’t cause you to get fatter. To quote researchers from the University of Hawaii, who conducted an extensive review of sugar-related literature:

“It is important to state at the outset that there is no direct connection between added sugars intake and obesity unless excessive consumption of sugar-containing beverages and foods leads to energy imbalance and the resultant weight gain.”

Overconsumption and energy imbalance are the keys here. The real problem with foods that contain added sugars is they make it easier to overeat.

One other health-related concern is the fact that eating a lot of foods with added sugars can reduce the amount of micronutrients your body gets and thus cause deficiencies. Many foods with added sugars just don’t have much in the way of essential vitamins and minerals.

The bottom line is lean, physically active people can regularly eat sugar (in moderation) with absolutely no negative side effects in terms of weight gain and metabolic health. I should know because I’m one of them!

The Solution

Get the majority of your calories from unprocessed, nutrient-dense foods, but feel free to include a bit of daily sugar in your meal planning if you so desire and you’ll be fine.

Personally, I never get more than 10% of my daily calories from added sugars simply because I cook my own meals and don’t have a sweet tooth. Considering how much micronutrient-dense food I eat and how much I exercise, this low level of sugar intake will never cause me any problems.

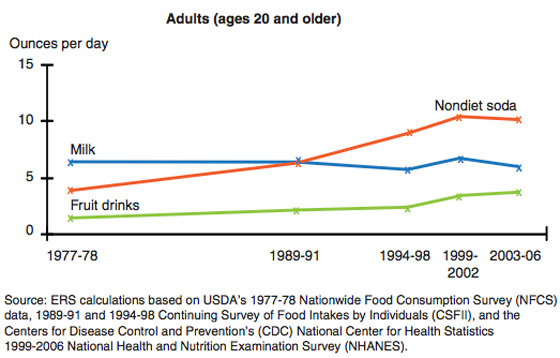

3. We’re drinking more caloric beverages than ever.

Here’s a simple dietary rule of thumb: if you love caloric beverages, you’ll probably be fat forever.

The major problem with caloric beverages, ranging from soda to sports and energy drinks to fruit juices, is they don’t trigger satiety like food.

You can drink 1,000 calories and be hungry an hour later, whereas eating 1,000 calories of food, including a good portion of protein and fiber, will probably keep you full for 5 to 6 hours.

Here’s a quote from researchers from Purdue University, who investigated the influence of meal timing and food form on daily energy intake:

“Based on the appetitive findings, consumption of an energy-yielding beverage either with a meal or as a snack poses a greater risk for promoting positive energy than macronutrient-matched semisolid or solid foods consumed at these times.”

That is, people that drink calories are much more likely to overeat than those that don’t.This is why research shows a clear association between greater intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain, in both adults and children.

The Solution

Cut back on or cut out altogether caloric beverages, and you’ll be better for it.

Learn to drink plain water and you’ll not only reap the many health benefits of staying hydrated, your body will burn more calories too.

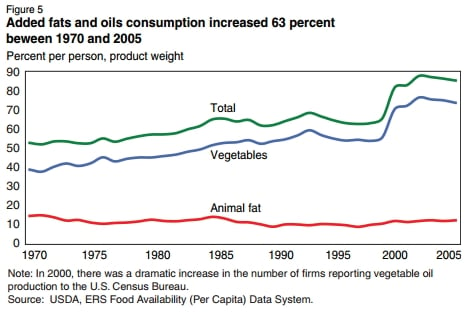

4. Our diets are fattier than ever.

Dietary fat intake has been steadily rising for the last five decades and has simply exploded in the last 15 years.

This isn’t all bad.

The move away from low-fat foods has helped people increase the amount of home-prepared, unprocessed foods in their diets, and dietary fats play a vital role in the body–they’re used in processes related to cell maintenance, hormone production, insulin sensitivity, and more.

The problem with high-fat dieting, however, is the fact that fats are so damn tasty and energy dense but not filling.

A gram of fat contains about 9 calories whereas a gram of protein or carbohydrate contains about 4 calories, but the fat isn’t as satiating as the other two. This is why research shows it’s easier to overeat on a high-fat diet and that obesity is greater among high-fat dieters than low-fat.

The Solution

The Institute of Medicine recommends that adults should get 20 to 35% of their daily calories from dietary fat, and if you exercise regularly, there’s no good reason to eat more than this.

Instead of a high-fat diet, you’ll be much better served by a high-carbohydrate diet, even when the goal is fat loss.

5. We’re sleeping less than ever.

There are two reasons why getting adequate sleep is an important part of preventing weight gain.

Your body burns quite a few calories while you sleep.

A 160-lb. person burns about 70 calories per hour, and much of it must come from fat stores because your body is in a fasted state, which means there’s no food energy available and insulin is at a baseline level.

Much of your body’s growth hormone is produced while you’re sleeping.

Growth hormone is a powerful lipolytic hormone, meaning it stimulates fat loss, and your body produces a large amount while you sleep.

Thus, it’s not surprising that research shows the amount we sleep affects our weight-loss efforts in addition to our overall health.

In a study conducted by the University of Chicago, 10 overweight adults followed a weight-loss diet (caloric restriction) for 2 weeks. One group slept 8.5 hours per night; the other, 5.5. The 5.5-hour group lost 55% less fat and 60% more muscle than the 8.5-hour group, and on top of that, they experienced increased hunger throughout the day.

This correlation has been observed elsewhere as well.

Research conducted by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine associated shorter sleep duration with increased levels of body fat. There’s also evidence that acute sleep loss causes insulin resistance to a level similar to someone with type 2 diabetes, which can increase the rate at which your body stores carbohydrates as fat.

The Solution

Sleep needs vary from individual to individual, but according to the National Sleep Foundation, adults need 7–9 hours of sleep per night to avoid the negative effects of sleep deprivation.

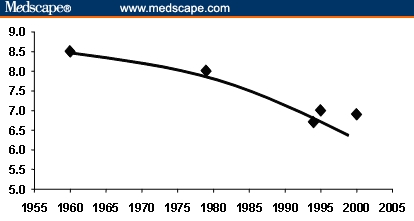

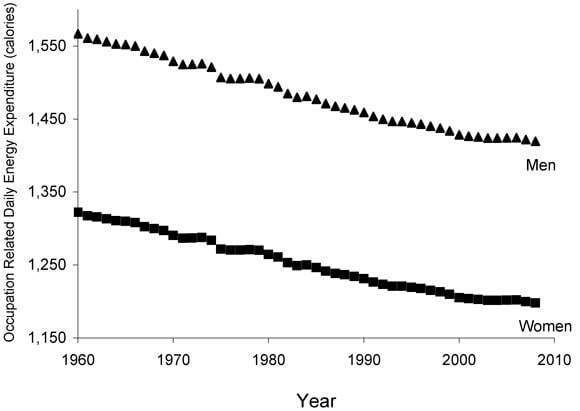

6. We’re burning less energy working than ever.

In the early 1960s, almost half of the jobs in the private sector required at least moderate physical activity. Today, only 20% of jobs are equally demanding.

Accordingly, Americans’ average daily energy expenditure has dropped by over 100 calories since the ’60s, and if that doesn’t sound too bad to you, consider this:

Eating 100 calories more than you burn every day, for a year, will add about 10 pounds of fat to your body.

That said, burning 100 calories less per day wouldn’t be a big deal if we also reduced our calorie intake accordingly. People aren’t doing that though, which we’ll talk about in a second…

The Solution

Sedentary living is incredibly unhealthy. If you live a sedentary lifestyle–if your average day takes you from the bed to the car to the desk to the car to the couch and back to the bed–you’re probably going to have serious health problems one day. It’s that simple.

A big part of staying lean and healthy is regular physical activity, and the best way to incorporate this is regular exercise, whether in the gym or through physically demanding hobbies.

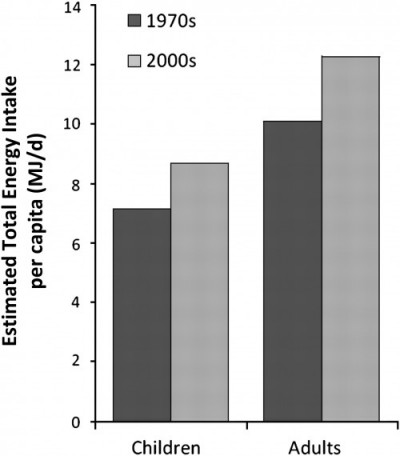

7. We’re eating more calories than ever.

I thought I would end on a bang, so here’s the bottom line to this entire article:

The amount of calories we eat on a daily basis has dramatically increased over the last several decades, and this alone is enough to explain the equally dramatic rise in obesity rates.

When you look over the previous six points, the picture is abundantly clear: people just eat too damn much and move too damn little, and if they flipped that around–ate less and moved more–they would “magically” lose the excess weight and avoid the many health risks that come with being overweight.

All the mainstream fear mongering about wheat and grains, carbohydrates in general, sugar, GMOs, and the rest of it obscures this basic truth, and sends people off on unproductive dietary witch hunts.

The key to weight loss and maintenance is, and always will be, balancing energy intake with energy output.

What are your thoughts on why people are fatter than ever? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- National Heart, L. and B. I. (n.d.). Overweight and Obesity | NHLBI, NIH. Retrieved March 25, 2021, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/overweight-and-obesity

- Swinburn, B., Sacks, G., & Ravussin, E. (2009). Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(6), 1453–1456. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28595

- Koster, A., Caserotti, P., Patel, K. V., Matthews, C. E., Berrigan, D., Van Domelen, D. R., Brychta, R. J., Chen, K. Y., & Harris, T. B. (2012). Association of Sedentary Time with Mortality Independent of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity. PLoS ONE, 7(6), e37696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037696

- Church, T. S., Thomas, D. M., Tudor-Locke, C., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Earnest, C. P., Rodarte, R. Q., Martin, C. K., Blair, S. N., & Bouchard, C. (2011). Trends over 5 Decades in U.S. Occupation-Related Physical Activity and Their Associations with Obesity. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e19657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019657

- Jitomir, J., & Willoughby, D. S. (2009). Cassia cinnamon for the attenuation of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance resulting from sleep loss. Journal of Medicinal Food, 12(3), 467–472. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2008.0128

- Yi, S., Nakagawa, T., Yamamoto, S., Mizoue, T., Takahashi, Y., Noda, M., & Matsushita, Y. (2013). Short sleep duration in association with CT-scanned abdominal fat areas: The Hitachi Health Study. International Journal of Obesity, 37(1), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2012.17

- Nedeltcheva, A. V., Kilkus, J. M., Imperial, J., Schoeller, D. A., & Penev, P. D. (2010). Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity. Annals of Internal Medicine, 153(7), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00006

- Dietz, J., & Schwartz, J. (1991). Growth hormone alters lipolysis and hormone-sensitive lipase activity in 3T3-F442A adipocytes. Metabolism, 40(8), 800–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(91)90006-I

- Van Cauter, E., & Plat, L. (1996). Physiology of growth hormone secretion during sleep. Journal of Pediatrics, 128(5 II). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70008-2

- Bludell, J. E., Lawton, C. L., Cotton, J. R., & Macdiarmid, J. I. (1996). Control of Human Appetite: Implications for The Intake of Dietary Fat. Annual Review of Nutrition, 16(1), 285–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.001441

- Rolls, B. J. (1995). Carbohydrates, fats, and satiety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 61(4 SUPPL.). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/61.4.960S

- Hennink, S. D., & Jeroen Maljaars, P. W. (2013). Fats and satiety. In Satiation, Satiety and the Control of Food Intake (pp. 143–165). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857098719.3.143

- Muckelbauer, R., Sarganas, G., Grüneis, A., & Müller-Nordhorn, J. (2013). Association between water consumption and body weight outcomes: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 98(2), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.055061

- Popkin, B. M., D’Anci, K. E., & Rosenberg, I. H. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. In Nutrition Reviews (Vol. 68, Issue 8, pp. 439–458). Blackwell Publishing Inc. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x

- Malik, V. S., Schulze, M. B., & Hu, F. B. (2006). Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. In American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 84, Issue 2, pp. 274–288). American Society for Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274

- Mattes, R. D., & Campbell, W. W. (2009). Effects of Food Form and Timing of Ingestion on Appetite and Energy Intake in Lean Young Adults and in Young Adults with Obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(3), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.031

- DiMeglio, D. P., & Mattes, R. D. (2000). Liquid versus solid carbohydrate: Effects on food intake and body weight. International Journal of Obesity, 24(6), 794–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801229

- Gibson, S. A. (2007). Dietary sugars intake and micronutrient adequacy: A systematic review of the evidence. In Nutrition Research Reviews (Vol. 20, Issue 2, pp. 121–131). Nutr Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422407797846

- Murphy, S. P., & Johnson, R. K. (2003). The scientific basis of recent US guidance on sugars intake. In The American journal of clinical nutrition (Vol. 78, Issue 4). Am J Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/78.4.827s

- Joosen, A. M. C. P., & Westerterp, K. R. (2006). Energy expenditure during overfeeding. Nutrition and Metabolism, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-3-25

- Jeppesen, J., Schaaf, P., Jones, C., Zhou, M. Y., Ida Chen, Y. D., & Reaven, G. M. (1997). Effects of low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets on risk factors for ischemic heart disease in postmenopausal women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65(4), 1027–1033. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1027

- Willett, W., Manson, J., & Liu, S. (2002). Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.1.274s

- Currie Stefano DellaVigna Enrico Moretti Vikram Pathania, J., Goodman, J., Machado, C., Simeonova, E., Schmeider, J., Hempstead, K., Weinberg, M., Currie, J., DellaVigna, S., Moretti, E., & Pathania, V. (2009). THE EFFECT OF FAST FOOD RESTAURANTS ON OBESITY AND WEIGHT GAIN. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14721

- Pereira, M. A., Kartashov, A. I., Ebbeling, C. B., Van Horn, L., Slattery, M. L., Jacobs, P. D. R., & Ludwig, D. S. (2005). Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet, 365(9453), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0

- Bowman, S. A., & Vinyard, B. T. (2004). Fast Food Consumption of U.S. Adults: Impact on Energy and Nutrient Intakes and Overweight Status. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(2), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719357

- Major, G. C., Doucet, E., Jacqmain, M., St-onge, M., Bouchard, C., & Tremblay, A. (2008). Multivitamin and dietary supplements, body weight and appetite: Results from a cross-sectional and a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Nutrition, 99(5), 1157–1167. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114507853335