Key Takeaways

- Agmatine is a neurotransmitter created in the body that’s been investigated as a treatment for numerous diseases and health disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and ischemic stroke.

- Agmatine likely helps reduce pain caused by several health conditions, including joint pain, but it probably doesn’t do much else.

- Keep reading to learn exactly what agmatine sulfate is, what the benefits of supplementing with it are, what the clinically effective dose is, and more.

People say you’re as old as you feel.

It’s probably more accurate to say you’re as old as your joints feel.

And that’s especially true for us fitness folk, because nothing can put the kibosh on our lifestyle like joint problems.

Temperamental shoulders can basically shut down your upper body workouts. Achy knees will give you a whole new reason to dread cardio and leg days. And a bitter lower back can get in the way of just about everything you like to do in and out of the gym.

This is why the supplement industry is awash with joint health supplements.

A new supplement that’s been getting more and more attention recently is agmatine sulfate.

Some people claim agmatine is a cure-all capable of easing joint pain, improving memory, and treating a number of health issues like Alzheimer’s and depression.

Others claim agmatine is just another gimcrack biohack that’s only popular thanks to bad research, false hopes, and underhanded marketing.

Who’s right?

The short answer is that agmatine sulfate isn’t complete bunk—it does have some benefits, but its benefits have been largely oversold.

Ready for the long answer?

Keep reading.

What Is Agmatine Sulphate?

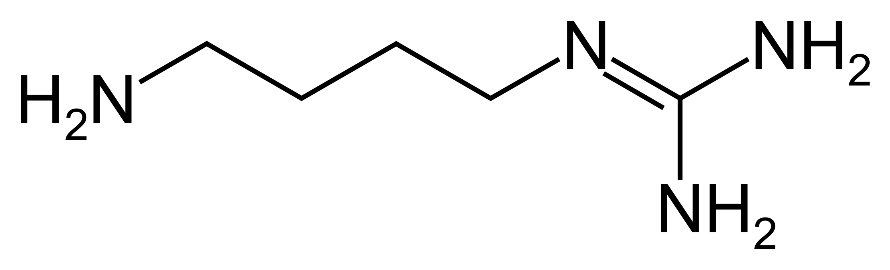

Agmatine is a neurotransmitter created in the body from the amino acid L-arginine.

You’ll rarely find agmatine as a standalone supplement, though, because it isn’t absorbed well by the body, and what little is absorbed often ends up being broken down into less beneficial byproducts.

Thus, agmatine is usually combined with another substance known as sulfate, which improves the absorption of agmatine in the body.

A neurotransmitter is a chemical messenger that helps transmit messages to neurons from the brain or to muscles from neurons.

Research shows that agmatine binds to many different neurotransmitter receptors in the body, which means it can alter body chemistry in myriad ways.

Most of the agmatine in the human body is found in the gut, though small amounts are also produced by mitochondria in the liver.

Trace amounts of agmatine are also found in many foods such as wine, beer, coffee, bread, fish, meat, fermented vegetables, and dairy products.

Despite being discovered in 1910, research into how agmatine affects humans is relatively new. This is mostly due to the fact that scientists didn’t believe agmatine was synthesized by mammals (including humans) until 1994.

As you’ll learn in a moment, it’s pretty clear that agmatine isn’t bad for humans, but researchers are still determining how it might be beneficial, too. This is why there are many different studies looking at how agmatine might enhance particular attributes (such as cognitive function) or reduce the risk or severity of many different diseases (such as Alzheimer’s).

Summary: Agmatine is a naturally-occurring neurotransmitter that binds to many different neurotransmitter receptors and can alter body chemistry in many different ways.

What Are the Benefits of Agmatine Sulphate?

Agmatine has been extensively studied as a treatment for a wide range of health problems, though most of the research has been done in rodents.

That said, a lot of the research is promising. Rodent studies show that agmatine may:

- Prevent the damage caused by a restriction of blood and oxygen to the brain

- Limit the accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles and plaque which are often contributors to Alzheimer’s disease

- Play a role in nerve regeneration

- Prevent seizures

- Protect brain cells from high levels of the stress hormone cortisol

- Decrease anxiety and stress

- Improve insulin sensitivity and reverse insulin resistance

- Increase “good” cholesterol and reduce arterial hardening

- Reduce systemic inflammation

- Prevent the growth of cancerous tumours

- Prevent symptoms of substance withdrawal

- Reduce weight gain, increase fat burning, and increase muscle mass

All of which sounds great, and is why you can find scores of Reddit users raving about how agmatine can do everything from curing depression to sharpening memory to helping injuries heal faster.

How much stock should you put in all of this, though?

Considering none of these results have been replicated in humans, not much. In fact, much of the hoopla over agmatine sulfate is based on nothing more than obscure rodent studies, which often produce promising results that don’t pan out in humans.

That said, studies on humans have shown that agmatine may help reduce pain.

This is particularly important to us fitness folk, who’re often plagued by minor aches and pains.

Agmatine Sulfate and Pain

The most scientifically valid claim related to agmatine sulfate is that it can reduce pain.

For example, a study conducted by scientists at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center had men and women aged 22 to 75 take either a placebo or agmatine sulfate for two weeks. All of the participants suffered from movement disabilities or pain due to herniated discs in their lower back.

The researchers found that the people who supplemented with agmatine sulfate experienced a significant improvement in their symptoms and quality of life compared to those who took the placebo.

The only side effect was that three participants experienced a brief bout of mild diarrhea and nausea two to three days after taking the highest dose of agmatine administered in the experiment (3.56 grams per day). The symptoms only lasted for one to two days, though.

Luckily, this dose was much higher than needed to experience the benefits (the only reason the researchers gave them this dose was to see how much they needed to take before experiencing side effects). In other words, you don’t need to take this much to reap the rewards.

Another study conducted by scientists at the JFK Medical Center gave agmatine sulfate to 11 overweight or obese men and women aged between 52 and 81, all of whom suffered from chronic pain caused by a condition called small fiber neuropathy (SFN).

SFN is a condition that involves severe, random bouts of pain that feels like stabbing, burning, or abnormal skin sensations (like tingling or itchiness). The pain typically starts in the hands and feet and is usually caused by damaged nerve cells. This tends to be more common among people who are overweight and/or who have diabetes, affecting up to 50% of people who have prediabetes or diabetes.

In this study, participants took six capsules of agmatine sulfate per day (spread out in two to three doses throughout the day, and taken with meals) containing a total of 2.67 grams of agmatine sulfate for two months.

Before and after the study, the participants answered a pain questionnaire that had been specifically developed for identifying and quantifying symptoms of SFN.

Participants answered each question using a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being the most severe pain possible.

The results showed that, compared to their level of pain at the beginning of the study, the participants who took agmatine sulfate experienced a 46% reduction in pain on average with no negative side effects.

Thus, on the whole, there’s good evidence that supplementing with agmatine sulfate could reduce pain caused by several different conditions.

This doesn’t mean it’s guaranteed to reduce pain caused by all injuries and ailments, but considering the low risk of side effects, it’s probably not going to hurt, either.

The bottom line is that if you suffer from joint aches and pains, agmatine sulphate may help take the edge off, but don’t expect miracles.

Summary: There’s good evidence that supplementing with agmatine sulfate reduces pain caused by several different conditions, and could reduce joint pain, too.

What Is the Clinically Effective Dose of Agmatine Sulfate?

There haven’t been enough studies on agmatine sulfate to establish what the clinically effective dose is, but research suggests you can get benefits from doses ranging from a few hundred milligrams to several grams.

One thing we do know, though, is that agmatine seems to be very safe, even in high doses.

For example, studies show that people taking 2.67 grams of agmatine sulfate per day for 5 years experienced no negative side effects.

Summary: The clinically effective dose of agmatine isn’t established yet, but research suggests a wide range of efficacy, from hundreds of milligrams to several grams.

The Best Agmatine Sulphate Supplement

While the evidence on agmatine sulfate is encouraging, more research is needed before we can definitively say it should be a key part of your supplementation regimen.

In other words, it’s probably not worth taking agmatine sulfate as a standalone supplement for joint health in the same way you might take whey protein and creatine monohydrate to help build muscle. When it comes to joint health supplements, it’s a supporting character—not the lead protagonist.

Thus, it’s best to take agmatine with other supplements that have been proven to improve joint health and reduce joint pain, like Fortify.

It’s a 100% natural joint supplement that enhances joint health and function by reducing inflammation and preserving cartilage.

Fortify contains 500 milligrams of agmatine sulfate per serving along with clinically effective doses of five other ingredients designed to improve joint health and function and reduce degeneration and pain, including . . .

- Undenatured type II collagen, which helps “teach” the body’s immune system to stop attacking the collagen in your joints.

- Curcumin, which inhibits a pro-inflammatory enzyme known as cyclooxygenase (COX) which can cause achy, painful joints.

- Boswellia serrata, which reduces joint inflammation and pain and inhibits an autoimmune response that can eat away at joint cartilage and eventually cause arthritis.

- Grape seed extract, which helps protect joints from damage in much the same way as Boswellia serrata.

- Vitamin C, which decreases the risk of developing Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, a difficult-to-diagnose form of chronic pain that typically develops after an injury.

You could take all of these ingredients separately, or you could just take Fortify, which provides clinically effective doses of each ingredient.

So, if you want healthy, functional, and pain-free joints that can withstand the demands of your active lifestyle and even the toughest training . . . you want to try Fortify today.

The Bottom Line On Agmatine Sulfate

Agmatine is a neurotransmitter created in the body, and found mainly in the gut and liver.

It binds to many different neurotransmitter receptors in the body and can affect the body in many different ways, which is why it’s been studied as a way to reduce the risk and severity of myriad diseases.

Up to this point, however, the only thing agmatine sulfate has been proven to treat in humans is pain caused by several different health conditions, including joint pain.

Scientists are still figuring out the clinically effective dose of agmatine sulfate, but most studies show you can get the pain-relieving benefits from doses ranging from a few hundred milligrams to several grams.

What we do know, though, is agmatine sulfate seems to be very safe, even when you take high doses for long periods of time.

Although agmatine sulfate may slightly reduce pain, it’s probably best to take it with other ingredients that have been proven to support joint health, like the ones found in Fortify.

Fortify is a 100% natural joint supplement that enhances joint health and function by reducing inflammation and preserving cartilage, and that only contains clinically effective doses of ingredients that are backed by peer-reviewed scientific research.

So, if you want healthy, functional, and pain-free joints . . . you want to try Fortify today.

What’s your take on agmatine sulfate? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Aïm, F., Klouche, S., Frison, A., Bauer, T., & Hardy, P. (2017). Efficacy of vitamin C in preventing complex regional pain syndrome after wrist fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research, 103(3), 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2016.12.021

- Yang, H., Lee, B. K., Kook, K. H., Jung, Y. S., & Ahn, J. (2012). Protective effect of grape seed extract against oxidative stress-induced cell death in a staurosporine-differentiated retinal ganglion cell line. Current Eye Research, 37(4), 339–344. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2011.645106

- Park, M. K., Park, J. S., Cho, M. La, Oh, H. J., Heo, Y. J., Woo, Y. J., Heo, Y. M., Park, M. J., Park, H. S., Park, S. H., Kim, H. Y., & Min, J. K. (2011). Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract (GSPE) differentially regulates Foxp3 + regulatory and IL-17 + pathogenic T cell in autoimmune arthritis. Immunology Letters, 135(1–2), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2010.09.011

- Kimmatkar, N., Thawani, V., Hingorani, L., & Khiyani, R. (2003). Efficacy and tolerability of Boswellia serrata extract in treatment of osteoarthritis of knee - A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine, 10(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1078/094471103321648593

- Aggarwal, S., Ichikawa, H., Takada, Y., Sandur, S. K., Shishodia, S., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2006). Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) down-regulates expression of cell proliferation and antiapoptotic and metastatic gene products through suppression of IκBα kinase and Akt activation. Molecular Pharmacology, 69(1), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.105.017400

- Lugo, J. P., Saiyed, Z. M., Lau, F. C., Molina, J. P. L., Pakdaman, M. N., Shamie, A. N., & Udani, J. K. (2013). Undenatured type II collagen (UC-II®) for joint support: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 10, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-10-48

- Gilad, G. M., & Gilad, V. H. (2014). Long-term (5 years), high daily dosage of dietary agmatine - Evidence of safety: A case report. Journal of Medicinal Food, 17(11), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2014.0026

- Hovaguimian, A., & Gibbons, C. H. (2011). Diagnosis and treatment of pain in small-fiber neuropathy. In Current Pain and Headache Reports (Vol. 15, Issue 3, pp. 193–200). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-011-0181-7

- Rosenberg, M. L., Tohidi, V., Sherwood, K., Gayen, S., Medel, R., & Gilad, G. M. (2020). Evidence for dietary agmatine sulfate effectiveness in neuropathies associated with painful small fiber neuropathy. A pilot open-label consecutive case series study. Nutrients, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020576

- Keynan, O., Mirovsky, Y., Dekel, S., Gilad, V. H., & Gilad, G. M. (2010). Safety and efficacy of dietary agmatine sulfate in lumbar disc-associated radiculopathy. An open-label, dose-escalating study followed by a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain Medicine, 11(3), 356–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00808.x

- Nissim, I., Horyn, O., Daikhin, Y., Chen, P., Li, C., Wehrli, S. L., Nissim, I., & Yudkoff, M. (2014). The molecular and metabolic influence of long term agmatine consumption. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(14), 9710–9729. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.544726

- Taksande, B. G., Kotagale, N. R., Patel, M. R., Shelkar, G. P., Ugale, R. R., & Chopde, C. T. (2010). Agmatine, an endogenous imidazoline receptor ligand modulates ethanol anxiolysis and withdrawal anxiety in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology, 637(1–3), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.058

- Uzbay, T., Yeşilyurt, Ö., Çelik, T., Ergün, H., & Işimer, A. (2000). Effects of agmatine on ethanol withdrawal syndrome in rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 107(1–2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4328(99)00127-8

- Molderings, G. J., Kribben, B., Heinen, A., Schröder, D., Brüss, M., & Göthert, M. (2004). Intestinal tumor and agmatine (Decarboxylated arginine): Low content in colon carcinoma tissue specimens and inhibitory effect on tumor cell proliferation in vitro. Cancer, 101(4), 858–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20407

- Arndt, M. A., Battaglia, V., Parisi, E., Lortie, M. J., Isome, M., Baskerville, C., Pizzo, D. P., Ientile, R., Colombatto, S., Toninello, A., & Satriano, J. (2009). The arginine metabolite agmatine protects mitochondrial function and confers resistance to cellular apoptosis. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology, 296(6), C1411. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2008

- Nowotarski, S. L., Woster, P. M., & Casero, R. A. (2013). Polyamines and cancer: implications for chemotherapy and chemoprevention. In Expert reviews in molecular medicine (Vol. 15, p. e3). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1017/erm.2013.3

- Ji-fang Wang, Rui-bin Su, Ning Wu, Bo Xu, Xin-qiang Lu, Yin Liu, & Jin Li. (n.d.). Inhibitory effect of agmatine on proliferation of tumor cells by modulation of polyamine metabolism - PubMed. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15842783/

- Wiśniewska, A., Olszanecki, R., Totoń-Żurańska, J., Kuś, K., Stachowicz, A., Suski, M., Gȩbska, A., Gajda, M., Jawién, J., & Korbut, R. (2017). Anti-atherosclerotic action of agmatine in ApoE-knockout mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18081706

- Sharawy, M. H., El-Awady, M. S., Megahed, N., & Gameil, N. M. (2016). Attenuation of insulin resistance in rats by agmatine: Role of SREBP-1c, mTOR and GLUT-2. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 389(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-015-1174-6

- Nissim, I., Horyn, O., Daikhin, Y., Chen, P., Li, C., Wehrli, S. L., Nissim, I., & Yudkoff, M. (2014). The molecular and metabolic influence of long term agmatine consumption. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(14), 9710–9729. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.544726

- Kang, S., Kim, C. H., Jung, H., Kim, E., Song, H. T., & Lee, J. E. (2017). Agmatine ameliorates type 2 diabetes induced-Alzheimer’s disease-like alterations in high-fat diet-fed mice via reactivation of blunted insulin signalling. Neuropharmacology, 113(Pt A), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.10.029

- Aricioglu, F., & Regunathan, S. (2005). Agmatine attenuates stress- and lipopolysaccharide-induced fever in rats. Physiology and Behavior, 85(3), 370–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.05.004

- Aricioglu, F., & Altunbas, H. (2003). Is Agmatine an Endogenous Anxiolytic/Antidepressant Agent? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1009, 136–140. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1304.014

- Freitas, A. E., Egea, J., Buendia, I., Gómez-Rangel, V., Parada, E., Navarro, E., Casas, A. I., Wojnicz, A., Ortiz, J. A., Cuadrado, A., Ruiz-Nuño, A., Rodrigues, A. L. S., & Lopez, M. G. (2016). Agmatine, by Improving Neuroplasticity Markers and Inducing Nrf2, Prevents Corticosterone-Induced Depressive-Like Behavior in Mice. Molecular Neurobiology, 53(5), 3030–3045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-015-9182-6

- Demehri, S., Homayoun, H., Honar, H., Riazi, K., Vafaie, K., Roushanzamir, F., & Dehpour, A. R. (2003). Agmatine exerts anticonvulsant effect in mice: Modulation by α2-adrenoceptors and nitric oxide. Neuropharmacology, 45(4), 534–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0028-3908(03)00199-0

- Bence, A. K., Worthen, D. R., Stables, J. P., & Crooks, P. A. (2003). An in vivo evaluation of the antiseizure activity and acute neurotoxicity of agmatine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 74(3), 771–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-3057(02)01079-1

- Surmelioglu, O., Sencar, L., Ozdemir, S., Tarkan, O., Dagkiran, M., Surmelioglu, N., Tuncer, U., & Polat, S. (2017). Effects of agmatine sulphate on facial nerve injuries. Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 131(3), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215117000147

- Kang, S., Kim, C. H., Jung, H., Kim, E., Song, H. T., & Lee, J. E. (2017). Agmatine ameliorates type 2 diabetes induced-Alzheimer’s disease-like alterations in high-fat diet-fed mice via reactivation of blunted insulin signalling. Neuropharmacology, 113(Pt A), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.10.029

- Song, J., Hur, B. E., Bokara, K. K., Yang, W., Cho, H. J., Park, K. A., Lee, W. T., Lee, K. M., & Lee, J. E. (2014). Agmatine improves cognitive dysfunction and prevents cell death in a streptozotocin-induced Alzheimer rat model. Yonsei Medical Journal, 55(3), 689–699. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2014.55.3.689

- Mun, C. H., Lee, W. T., Park, K. A., & Lee, J. E. (2010). Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by agmatine after transient global cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Anatomy & Cell Biology, 43(3), 230. https://doi.org/10.5115/acb.2010.43.3.230

- Tabor, C. W., & Tabor, H. (1984). Polyamines. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 53(1), 749–790. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533

- Kossel, A. (1910). Über das Agmatin. Hoppe-Seyler’s Zeitschrift Fur Physiologische Chemie, 66(3), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1515/bchm2.1910.66.3.257

- Galgano, F., Caruso, M., Condelli, N., & Favati, F. (2012). Focused review: Agmatine in fermented foods. Frontiers in Microbiology, 3(JUN). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00199

- Freitas, A. E., Neis, V. B., & Rodrigues, A. L. S. (2016). Agmatine, a potential novel therapeutic strategy for depression. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(12), 1885–1899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.10.013

- Swanson, K. S., Grieshop, C. M., Flickinger, E. A., Bauer, L. L., Wolf, B. W., Chow, J., Garleb, K. A., Williams, J. A., & Fahey, G. C. (2002). Fructooligosaccharides and Lactobacillus acidophilus modify bowel function and protein catabolites excreted by healthy humans. Journal of Nutrition, 132(10), 3042–3050. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/131.10.3042

- Uzbay, T. I. (2012). The pharmacological importance of agmatine in the brain. In Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews (Vol. 36, Issue 1, pp. 502–519). Neurosci Biobehav Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.08.006

- Molderings, G. J., & Haenisch, B. (2012). Agmatine (decarboxylated l-arginine): Physiological role and therapeutic potential. In Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Vol. 133, Issue 3, pp. 351–365). Pharmacol Ther. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.12.005

- Reis, D. J., & Regunathan, S. (1999). Agmatine: An endogenous ligand at imidazoline receptors is a novel neurotransmitter. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 881, 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09343.x

- Head, G. A., Chan, C. K. S., & Godwin, S. J. (1997). Central cardiovascular actions of agmatine, a putative clonidine-displacing substance, in conscious rabbits. Neurochemistry International, 30(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-0186(96)00044-7

- J E Piletz, D N Chikkala, & P Ernsberger. (n.d.). Comparison of the properties of agmatine and endogenous clonidine-displacing substance at imidazoline and alpha-2 adrenergic receptors - PubMed. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7853171/