Key Takeaways

- It’s difficult to accurately predict how strong you can get in your lifetime. You can use several calculators in this article to get a rough prediction, however.

- It will take years of consistent strength training to reach your natural potential for strength gain.

- The two most important things you can do to get as strong as possible are to do lots of heavy, compound weightlifting and build as much muscle as possible.

Some people say that with enough hard work, patience, and food, you can get as strong as you want.

It’s just a matter of your work ethic, grit, and #dedication.

On the other hand, others say that while you can gain plenty of strength relative to where you started, you’ll have achieved most of the strength available to you after just a few years of lifting.

You’ll find convincing arguments on both sides replete with research, anecdotes, and examples, and to even further muddy the waters, the runaway rise of steroid use has made the discussion even more convoluted.

Some people say steroids don’t impact strength much while others scoff at such claims and explain how steroids can skyrocket your strength to unnaturally high levels.

What to make of all this?

Well, we’re going to break it all down in this article, and the long and short is this:

If you’re new to weightlifting, you can get much stronger than you currently are, and if you’re an experienced lifter, you may still be able to get considerably stronger.

That said, it isn’t going to come easy—it’s going to take years of diligent, difficult, deliberate training and eating to get there.

What’s also true is that as a natural lifter, you’ll never be as strong as you would be with steroids. Just as with muscle gain, steroids give you a tremendous advantage with gaining strength.

So, by the end of this article, you’re going to have answers to all of your most pressing questions on getting as strong as possible, including:

- What is strength?

- What determines how strong you can get?

- How much do steroids help with strength gain?

- How strong can you get naturally?

- What rep range is best for gaining strength?

- And more.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

+

How Do You Assess Strength?

For many weightlifters, the bench press is the ultimate benchmark of strength. If you have a big bench, you’re strong, and if you don’t, you’re not.

This is shortsighted.

The bench press is a good measure of pushing strength, but what about the back and legs, which contain some of the largest muscles in the body? Would you say that someone with a strong bench press, but weak deadlift and squat, is truly “strong”?

Thus, if you want to gauge your strength, you want to evaluate your whole-body strength, and an effective way to do that is by appraising your performance of the following movements:

- Push

- Pull

- Squat

There are many pushing, pulling, and squatting exercises you could use to test your strength, but leading experts and strength coaches have settled on three:

- Barbell Squat

- Barbell Bench Press

- Barbell Deadlift

The barbell squat proves your lower body and back strength, the bench press your chest, shoulder, and arm strength, and the deadlift your back, hamstring, and glute strength.

Thus, if you add your squat, bench press, and deadlift one-rep maxes, you’ll have an accurate and practical estimate of your whole-body strength.

That said, while the sum of these lifts—referred to as your total—gives you a quantitative view of your strength in terms of absolute numbers, it doesn’t give you a qualitative one in terms of how those lifts relate to your size and stature.

In other words, if all you’re looking at is the weight on the bar, a squat of 600 pounds is far stronger than 400 pounds.

And by this standard, the strongest people are almost always going to be the biggest.

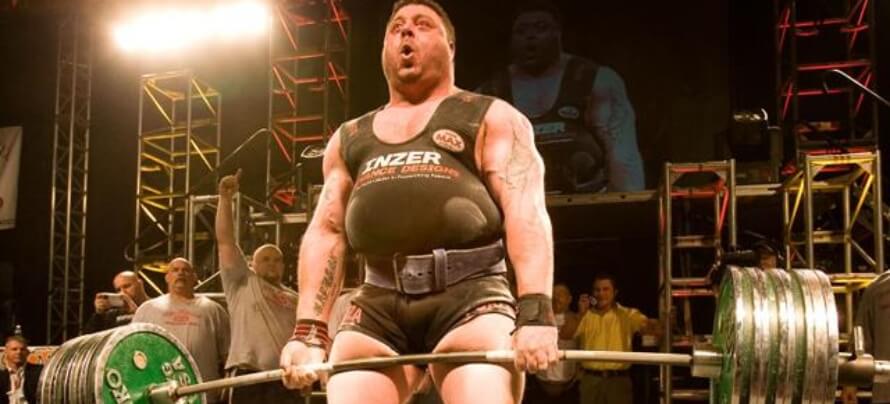

For instance, here’s strongman Hafthor Bjorrnson:

Hafthor is 6’9, 425 pounds, and has a combined squat, bench press, and deadlift of over 2,400 pounds, making him the strongest man in the world at the time of this writing.

Konstantīns Konstantinovs is another good example of the correlation between size and strength:

Konstantīns was 6’3, just under 300 pounds, and totaled over 2,100 pounds.

Andy Bolton was another giant at 6’3 and 360 pounds, and he totaled a jaw-dropping 2,800 pounds:

All very impressive, but also illustrative of this simple fact: generally speaking, the bigger someone naturally is, the more muscle and strength they can naturally gain.

But, going back to our example, what if the guy squatting 600 pounds is 6’2” and weighs 300 pounds, while the other is 5’8” and weighs 200 pounds? Which lift should we consider more impressive?

This is where relative strength enters the picture, which also accounts for body weight, and therefore allows us to compare the strength of people of different sizes.

In this way, someone who’s 5’5” and 130 pounds can see how their numbers stack up against someone who’s 7’2” and 400 pounds, and determine who’s getting the most out of what they’ve got.

You can’t just divide totals by body weights, though. Because of quirks of physics and biology, the mass (weight) of the human body increases faster than its strength. For example, if I magically doubled my body weight, I wouldn’t be twice as strong, and likewise, if I shrunk to half my current size, I wouldn’t be half as strong.

So how much do increases or decreases in body weight impact strength? To find the answer, we can use a technique known as allometric scaling, which is a method that helps scientists understand how different characteristics change in an organism as size changes.

For instance, thanks to this line of research, we know that for most animal species, as the body size increases, the metabolic rate per unit of mass decreases. (Good news for elephants, who still need to eat 200 to 600 pounds of food every day!)

Powerlifter, researcher, and writer Greg Nuckols gets all the credit here, as he’s the one who figured out how to make allometric scaling work for predicting strength in humans.

With a formula he created, you can calculate a number that represents your relative strength and then compare it to the figures of others to see where you stand.

Here’s the formula he created:

lift * weight ^ -2/3

The only problem is it looks like double Dutch to most of us, so instead of wading through the math, here’s a calculator that’ll do the heavy lifting (har har) for you:

Here’s how to use it:

- Select pounds or kilograms.

- Sum up your best squat, bench press, and deadlift one-rep-maxes and enter this in the Total field.

- Enter your body weight in the Weight field.

The resulting score is an evidence-based proxy for your relative strength.

Next, you can enter someone else’s information to see who’s relatively stronger between the two of you.

Keep in mind this calculator doesn’t indicate your natural potential for strength—just how strong you are right now—but we’ll get to that in a moment.

There are other formulas out there for calculating relative strength, such as the Wilks, Glossbrenner, and Schwartz/Malone coefficients, but they’re less accurate than Nuckols’ method. For example . . .

- It’s well known the Wilks coefficient misestimates the relative strength of people who weigh between 150 and 200 pounds.

- The Schwarz/Malone coefficient often overestimates the relative strength of people who weigh less than 150 pounds.

- The Glossbrenner coefficient more or less just averages the results from the Wilks and Schwarz/Malone coefficients, but this doesn’t overcome their flaws.

As Nuckols explains in his extensive article on the topic, allometric scaling may not be perfect, but it’s a better, scientifically-validated system for computing relative strength than the other popular methods.

Summary: The best way to assess relative strength is to sum up your squat, bench press, and deadlift one-rep maxes, and plug the total into the allometric scaling calculator on this page. Whoever has the higher score is stronger.

How Strong Can You Get Naturally?

Your ability to gain strength depends on a few factors, with the chief ones being your . . .

- Skill and attitude

- Bone length

- Muscle structure

- Muscle size

Let’s take a closer look at each.

Skill and Attitude

Strength is a skill.

Lifting large amounts of weight with proper technique requires outstanding balance, coordination, and timing, and that’s why your first squat, bench press, and deadlift sessions felt awkward, uncoordinated, and weak.

Accordingly, your strength is limited by not only your musculature but also your movement patterns, which are flawed and inefficient in the beginning.

After a month or two of regular practice, though, your technique can rapidly improve along with your strength. In fact, research shows that most of the strength people gain in their first month of lifting weights is the result of improvements in coordination and technique, not muscle growth.

These “technique gains” taper off quickly, though, and after a year of regular lifting, your ability to perform key exercises is about as good as it’ll ever be. You can still improve your skill as time goes on, but the process will be slow and subtle.

Read these articles to learn everything you need to know about proper squat, bench press, and deadlift technique:

-

How to Squat: The Definitive Guide (Plus 12 Proven Ways to Improve Your Squat!)

-

The Definitive Guide on How to Bench Press (and the 8 Best Variations!)

-

This Is the Definitive Guide on How to Deadlift (Safely and with Proper Form)

Your attitude in the gym matters, too, because approaching your genetic limit for strength requires a bit of piss and vinegar.

To get there, you will need to do a lot of heavy weightlifting, which means getting comfortable being uncomfortable, pushing yourself to add weight to the bar, and staying focused through weeks, months, and years of strenuous training.

In short, showing up and going through the motions isn’t enough. You have to strive to make every rep, set, and workout count.

If you want to learn how to improve your attitude, read these articles:

Summary: Your strength potential is affected by your skill and mindset as a weightlifter.

Bone Length

Every exercise involves moving a weight a certain way for a certain distance.

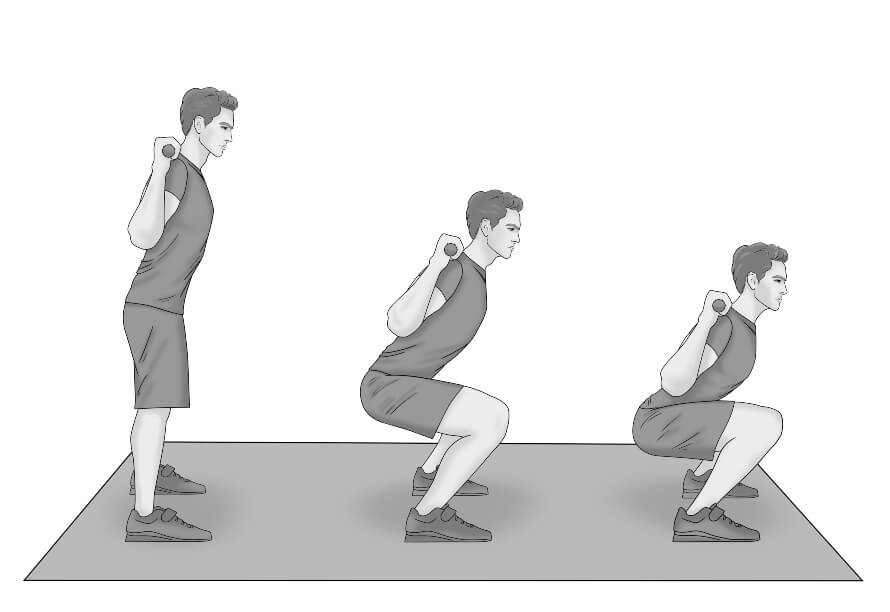

For example, a rep of squats looks like this:

Here’s the sequence:

- Standing position with the legs straight.

- Sitting position with your thighs more or less parallel with the floor.

- Standing position with the legs straight.

While small differences in individual anatomy don’t change this basic pattern, they can alter how easy or difficult the exercise is by changing how far the weight needs to move to perform each rep.

For example, if your femurs are longer than average, you’ll find the squat and deadlift more difficult, because the bar will have to travel a few inches farther every rep.

For the same reason, if your arms are longer than average, you’ll find the bench and military press more difficult, but the deadlift will be easier, because the bar won’t have to move as far to lock out.

Being 6’1” with long legs and arms, I’ve experienced this firsthand. The squat, bench press, and military press have always been the hardest to progress on, and my current personal bests are respectable, but nothing to write home about: a 365-pound squat for two or three reps, 295-pound bench for two reps, and 225-pound seated military press for two or three reps.

Deadlifting, however, has been somewhere in the middle for me, as my long legs make it harder, but long arms make it easier. My personal best is still just middling (435 pounds for two reps), but was easier to achieve than the other lifts.

I can’t blame my anatomy too much, though, because structural differences don’t have as big of an impact on strength gain as many people claim.

First, every inch of height only increases the distance the bar needs to move by a small amount.

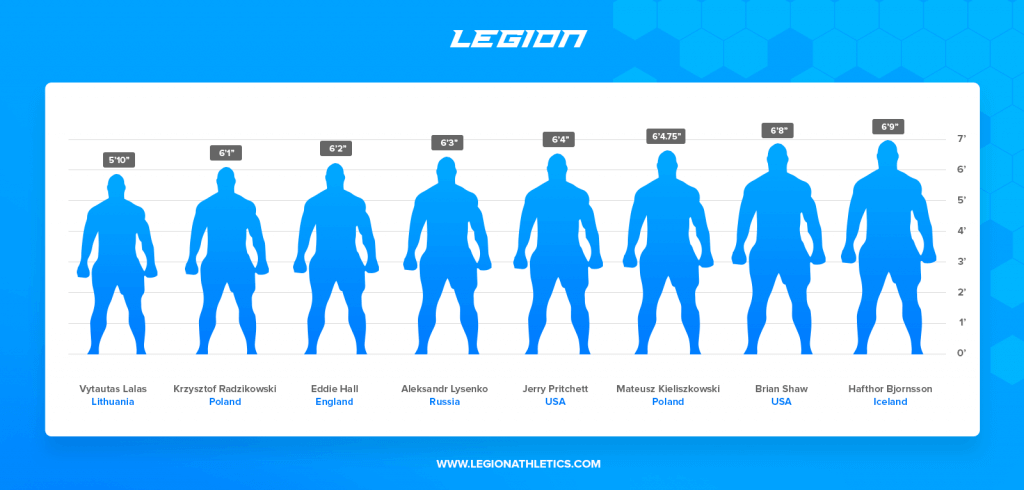

For instance, check out this chart of top-tier strongmen:

To get an idea of how their different heights affect how far the bar has to move during let’s say the deadlift and bench press, look at the hand height of the tallest competitor on the far right—6’9 Hafthor Bjornnson—and the shortest competitor—5’10 Vytautas Lalas.

Despite being 11 inches taller than Lalas, Bjornsson only needs to lift the bar about 6 inches further to complete a deadlift rep and 4 to 6 inches further on the bench press. And the second shortest guy on the list—the 6’1 Krzysztof Radzikowski—only needs to lift the bar about one inch further than 5’10 Lalas.

Of course, this is assuming these men have average limb-to-torso proportions, but by definition, most people do have average proportions, so it’s fair to assume that’s the case here.

So, my point is this: while taller people do need to move the weight a little further than shorter people, the differences aren’t very drastic.

Second, even having to move the bar an inch or two more doesn’t always significantly increase the difficulty of the exercise.

To understand why, you must understand that every exercise has a sticking point. This is a point in the movement where the exercise becomes more difficult, and it typically makes up about three to six inches of the total distance the weight needs to travel.

(It would be more accurate to describe this as a sticking range, since it’s a few inches, but I’ll stick with the more common term for the sake of familiarity.)

Despite comprising a fraction of the total exercise movement, the sticking point more or less dictates how difficult a rep will be. If you can move through this spot quickly, you’ll probably complete the rep without a hitch, and if you can’t, you’ll probably grind to a halt.

For instance, most people’s sticking point on the bench press is when the bar is three to six inches off their chest and continues for another three to six inches. Once you get the bar through this span of the ascent, the rest feels easy.

Here’s a typical example of a bench press sticking point:

How does this relate to bone length and strength?

I’ll use myself as an example again.

Compared to my 5’10” lifting partner, I have to move the bar about two to three inches farther to complete each rep of the bench press. Only an inch or two are added to my sticking point, though, while the rest of the additional distance isn’t as difficult.

And yes, that means my reps are harder than his and produce more fatigue as I get deeper into sets, but this isn’t likely to put me more than a rep or two behind him on most sets.

Something else to consider is the fact that taller people can often gain more total muscle than shorter people, which can help mitigate anatomical disadvantages. Additionally, having long bones may be a disadvantage in one exercise, but an advantage in another.

As I just mentioned, my long arms make bench pressing harder, but they also make deadlifting easier. My long femurs, on the other hand, make deadlifting and squatting harder and don’t help my bench press.

So all things considered, if someone can lift more weight than you, chances are that variations in height and proportions aren’t the driving factors. Instead, it likely has more to do with the other reasons we’ll discuss in this chapter, particularly muscle size.

Summary: Differences in height and limb length make some exercises harder and others easier, but this isn’t a major factor in someone’s strength. Moreover, in most people, the advantages and disadvantages tend to cancel each other out when looking at their total squat, bench press, and deadlift.

Muscle Structure

While we all have the same muscles in our bodies, and they’re all in the same general regions, there are differences in how they’re attached to our skeletons. These discrepancies are usually small—only a centimeter or two—but they can translate into huge differences in natural strength.

We don’t need to get too technical for this discussion, but what it boils down to is mechanical advantage. Because muscles function as levers, where they attach to our bones impacts how much force they can produce and thus how much weight they can move.

This is why studies have found that, thanks to this type of anatomical variance, strength can vary by as much as 25% among people with identical amounts of muscle mass.

If you’re worried that you’re in the disadvantaged camp, take heart, because this should only concern you if you’re trying to become a competitive strength athlete. However, if you’re here to build a strong, muscular, lean, healthy body, you can achieve your goals with or without a genetic leg up.

But do keep anatomy in mind when comparing yourself to other people of similar size—some bodies are just built better for strength than others.

Summary: In people with more or less identical body compositions, anatomical variations can drastically increase or decrease strength—up to 25%, according to some research.

Muscle Size

Generally, the biggest guys in the gym are also the strongest. Sure, there are exceptions, but more often than not, the people moving big loads are pretty jacked.

This is clear to anyone who has spent enough time with the iron, but it’s also backed by scientific research.

For instance, studies conducted by scientists at Indiana University and the University of San Martin found that muscle mass is strongly associated with strength among powerlifters.

This doesn’t mean that every pound you add to the barbell makes you a little more muscular, though, because strength and muscle gains aren’t perfectly correlated. In other words, you can get stronger without getting bigger and vice versa.

For example, most of the strength you gain during the first few weeks of lifting comes from getting better at exercises—those “technique gains” I mentioned earlier.

Your muscles contract harder and at the right times, your balance improves, and your technique becomes respectable. You still gain some muscle during this beginning period, but that only accounts for about 2% of the rather large jump in strength.

After you’ve worked out the bugs in your form, however, which happens in the first few months for most people, further increases in strength become largely dependent on gaining muscle. And after a couple of years of consistent training, research shows about 65% of your strength gain will come from muscle gain.

So, once your newbie gains are behind you, if you want to keep getting stronger, you’ll have to keep getting bigger. And once you reach your genetic potential for muscle growth, you won’t have much more strength available to you, either.

The best way to think of the relationship between muscle and strength is this: the amount of muscle you have represents your potential for strength.

For instance, let’s say you use lighter weights and higher reps during a lean bulk and gain five pounds of muscle. Since you weren’t using heavy loads and lower reps and are a bit “rusty” at that type of training, when you attempt to set new one-rep maxes, you fall short of your previous bests.

This might leave you confused or even crestfallen, but here’s the good news: if you were to train with heavy weights and low reps for four to six weeks, you’d likely beat your previous lifts.

Why?

Because those five additional pounds of muscle will allow you to generate more force than before. You just have to readapt your muscles to heavier loads and fewer reps.

Summary: Once your newbie gains are behind you, how much stronger you can get will largely depend on how much more muscle you can build.

What About Muscle Fiber Types?

No discussion of gaining strength would be complete without talking about muscle fiber types.

A muscle fiber is another term for a muscle cell, also known as a myocyte.

There are multiple kinds of muscle fibers, with some more suited to endurance activities (jogging) and others to power-based activities (sprinting) and others still somewhere in the middle.

(In sports, force is how much strength you can produce, or how much weight you can move, and power is how quickly you can produce force, or how fast you can move the weight. Thus, throwing a baseball requires a lot of power and a heavy set of squats requires a lot of force.)

The muscle fibers best suited to endurance activities are known as type l muscle fibers, or slow-twitch muscle fibers.

The muscle fibers best suited to power-based activities are known as type ll muscle fibers, or fast-twitch muscle fibers.

And the muscle fibers with properties of both fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers are known as hybrid muscle fibers.

There are still more questions than answers about how your body’s muscle fiber makeup affects your physical abilities, but here’s something we know with more or less certainty: It doesn’t matter for strength and muscle gain.

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but if muscle fiber type has any impact on our ability to gain muscle and strength, it’s small.

The reason for this is simple:

Slow, fast, and hybrid muscle fibers can all produce the same amount of force, but some types produce it faster than others.

As their name would suggest, fast-twitch muscle fibers can contract faster than slow-twitch muscle fibers, which makes them highly effective for sprinting, throwing, and other power-based sports.

You can produce maximum power when using weights that are about 30 to 60% of your one-rep max, and as the weights get heavier, your muscles produce less and less power as they struggle to move the weight quickly.

In other words, as the weights get heavier and into the “hypertrophy” range of 70%+ one-rep max, exercises are almost always performed slow enough for both fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers to produce maximal force.

And since all muscle fibers can produce about the same amount of force, the ratio of fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers in your body doesn’t much impact your performance.

That said, there’s a key difference between fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers that’s worth noting:

Fast-twitch muscle fibers can grow about 25 to 75% larger than slow-twitch muscle fibers, so if your body contained more or less fast-twitch muscle than average, you’d be able to gain more or less muscle size than average, which would in turn impact how strong you could get.

This is unlikely, though, as most people have a fairly even split between fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers. Research has even found that powerlifters have about the same ratio of fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers as couch potatoes.

If you want to learn more about how muscle fibers do (and don’t) affect your ability to gain strength and muscle, read this article:

⇨ What 30 Studies Say About Your Muscle Fiber Type and Muscle Growth

Summary: Your ratio of fast- to slow-twitch muscle fiber doesn’t have a significant impact on your ability to gain strength or muscle, and there’s nothing you can do to notably influence this ratio.

Do Steroids Help You Get Stronger?

Nobody can deny steroids help you build muscle faster, but many people question their ability to influence strength.

They’re wrong.

For one thing, as you now know, gaining muscle directly increases your ability to gain strength. The more muscle you gain, the stronger you can get.

How much stronger?

A study conducted by scientists at the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science provides an answer. In this study, researchers split 43 resistance-trained men ranging from 19 to 40 years of age into four groups:

- Group one consumed a placebo and didn’t lift weights.

- Group two was injected with 600 mg of testosterone and didn’t lift weights.

- Group three consumed a placebo and lifted weights.

- Group four was injected with 600 mg of testosterone and lifted weights.

Everyone followed this protocol for 10 weeks, and before and after the study, the researchers measured the participants’ weight, strength, and body composition.

And the results illustrate why steroids are so popular.

As expected, the guys who didn’t lift weights or take steroids didn’t gain any muscle to speak of and added a measly 7 pounds to their squat and nothing to their bench press.

The natty lifters in group three fared significantly better and gained about 4.5 pounds of muscle and added about 77 pounds to their squat and bench press, which is fantastic for 10 weeks of training.

They could’ve skipped all the workouts, though, and just injected testosterone instead.

On average, the men in group two who took steroids and sat on their butts for 10 weeks added 70 pounds to their squat and bench press and gained 7 pounds of muscle.

It gets better, too. The people in group four who took steroids and lifted weights . . .

- Increased their squat and bench press by a whopping 132 pounds

- Gained a mind-boggling 13.5 pounds of muscle

- Gained eight times more size in their triceps and twice as much size in their quads as the natty lifters

. . . in 10 freaking weeks.

Yes, they added 13 pounds to their squat and bench press and 1.3 pounds of muscle to their bodies per week.

And let’s not forget this study was on the effects of just testosterone, which are only further magnified by other popular anabolic steroids including dianabol, trenbolone, nandrolone, boldenone, oxandrolone, stanozolol, and others.

The second reason steroids are ubiquitous in strength sports is they allow you to recover from much larger volumes of training, which results in more strength and muscle gain over time.

If one lifter can do just 10 sets of heavy squats per week while another can crank out 30 sets per week, who do you think is going to gain more leg size and strength over time?

Weightlifters aren’t the only athletes who can benefit from enhanced recovery, of course. This is why athletes of all stripes take steroids. Even athletes who don’t want extra muscle mass, like professional cyclists, have been caught taking testosterone and other similar drugs to enhance their recovery.

Summary: Steroids directly increase muscle growth and strength and allow lifters to recover from more training than natural lifters can handle, which results in still more strength and muscle gains over time.

So . . . How Strong Can You Get Naturally?

I hate answering important questions like this with “it depends,” but that’s the truth here.

It’s hard to determine how strong you’ll be able to get, because there are too many factors in play. Unlike the potential for muscularity, there isn’t one individual variable that we can isolate and use as a guidepost for potential strength.

That said, there is a way to estimate how strong you can get.

It sounds simplistic, but it’s also commonsensical: Look at the performance of many other weightlifters similar to you in size. Chances are, you’ll fall somewhere in the middle.

While there are no comprehensive studies on strength potential, Greg Nuckols has conducted an unofficial study of the matter that lends some insight.

Nuckols collected survey responses from 1,800 experienced weightlifters of all sizes, used the allometric scaling method you learned about earlier to assess their relative strength levels, and then assigned their squat, bench press, and deadlift one-rep maxes, and total, into six categories:

- Beginner

- Novice

- Intermediate

- Advanced

- Elite

- World Class

He also created a calculator that allows you to find what category you fall into. Here it is:

To use this calculator, select which unit you’d like to use (pounds or kilograms) and enter your weight and height.

Based on those numbers, in the chart below, you’ll find targets for six levels of proficiency on the squat, bench, deadlift, and total.

For instance, when I plug in my height and weight, it says “beginner” level lifts for my size are 319 pounds on the squat, 213 pounds on the bench, and 359 pounds on the deadlift.

My all-time best one-rep maxes are 375 pounds on the squat, 300 pounds on the bench, and 445 pounds on the deadlift, which puts me in the novice category. And that’s not too shabby considering I’ve never trained to maximize my strength.

If I focused on nothing but strength training for a while, the best I (and most others, including you, probably) could hope for—regardless of how hard I tried—would be somewhere between intermediate and advanced (the middle of the curve).

With enough drugs, maybe I could reach the advanced tier, but no matter how much vitamin S I took, I’d never be able to put up elite or world-class numbers. It’s not in my bones (literally).

And I’m cool with that.

This data is based on a bunch of hardcore powerlifters, so as a natural recreational “bodybuilder,” high-level novice strength is decent and intermediate would be impressive.

Now, if this calculator’s numbers seem unrealistically high to you, remember—it’s using the averages of people who’ve been training for years and have likely achieved much or all of their genetic potential for muscle and strength.

Moreover, this data was collected anonymously through the Internet, so it’s very possible (all but guaranteed) that some people were on steroids or lied about their numbers.

Still, despite the obvious limitations, Nuckols’ calculator is one of the few of its kind that takes your personal anatomy into account, making it plenty useful.

If you’d like to look at another set of strength standards that are more achievable for most people (that unfortunately don’t take height into account), check out this article:

⇨ These Are the Best Strength Standards on the Internet

Summary: The best way to estimate your potential for strength is to look at the performance of many other weightlifters similar to you in size and see how you compare.

How to Gain Strength and Muscle Fast

If you want to get as strong as possible, you need effective training and diet plans.

You want to work hard in the gym but not so hard that you fall behind in recovery, and you want that work to result in maximum muscle and strength gain. That requires a systematic, intelligent approach to training.

Moreover, you want to gain as much muscle and little fat as possible, and that requires more than simply “eating big to get big.”

Fortunately, none of this is very complicated. There are just five simple steps:

- Do lots of heavy, compound strength training.

- Follow an effective strength training program.

- Eat slightly more calories than you burn.

- Eat a high-protein and high-carb diet.

- Take the right supplements.

1. Do lots of heavy, compound strength training.

To get stronger, you have to train with heavyweights. There’s no way around this.

When I say heavy, though, I don’t necessarily mean grinding out heavy singles, doubles, and triples every week.

Instead, I mean working with weights that are at least 60% of your one-rep max and taking most sets to 1 to 3 reps shy of technical failure.

Most people who are new to heavy weightlifting do very well with a template like this:

- 75% of sets in the 4-to-6-rep range with around 80% of one-rep max

- 25% of sets in the 8-to-10-rep range with around 70% of one-rep max

And if you’re a woman new to weightlifting, I recommend you do 100% of your sets in the 8-to-10 rep range at least for the first 6 to 12 months, at which point you should be plenty strong enough to safely and effectively incorporate heavier training into your workout routines.

If you want to learn how to calculate your one-rep maxes, read this article:

⇨ A Simple and Accurate One-Rep Max Calculator (and How to Use it)

2. Follow an effective strength training program.

Getting intensities and rep ranges right isn’t enough if you want to gain muscle and strength as quickly as possible.

You also need to follow a well-designed program that focuses on maximally effective exercises, revolves around progressive overload, and provides sufficient volume.

It also needs to give enough rest and recovery to ensure you can continue making progress without eventually getting burnt out, overtrained, or injured.

There are quite a few high-quality strength training programs out there. Learn more about them here:

⇨ The 12 Best Science-Based Strength Training Programs for Gaining Muscle and Strength

3. Eat slightly more calories than you burn.

You know that the most important determinant of strength gain is muscle gain. Once you’ve grooved in good technique, the only surefire way to keep getting stronger is to keep getting bigger.

What you may not know, however, is once you’ve exhausted your newbie gains, a surefire way to stall muscle growth is to eat too few calories.

There are various reasons for this, mainly physiological, but we don’t have to get into them here. All you need to know is that your body’s “muscle-building machinery” just works best when energy is abundant.

Eating enough food is doubly important if you want to gain strength, as your workouts will be much more productive when your body and muscles are full of energy.

Another major mistake that “hardgainers” often make is eating way too much. They assume that if slightly overeating is better for gaining muscle, then gorging themselves silly or drinking a gallon of milk a day is much better.

Unfortunately, it’s not.

You can’t force your muscles to get bigger or stronger by drowning them in calories, because beyond a certain point, food stops fueling training and recovery and just makes you fatter.

That’s why a slight calorie surplus of 10 to 15% is just as conducive to muscle growth as a larger surplus of 30% or more.

That is, all you have to do to optimize muscle growth is consistently eat just 10 to 15% more calories than you burn every day.

This is the point of diminishing returns, where increasing your calorie intake further contributes less and less to muscle building and more and more to fat gain.

And gaining too much fat does more than hurt your ego. It also makes it harder to build muscle by negatively impacting your insulin sensitivity, making it more likely that the calories you consume will be stored as fat, not muscle.

This is why you should shy away from “dirty bulking,” as bodybuilders call it, and opt to “lean bulk” instead.

This approach is a win-win because it allows you to maximize muscle growth and minimize fat gain.

And, just in case you’re curious, most people can gain muscle and fat at about a 1:1 ratio when they’re doing everything right.

In other words, if you gain a pound of muscle for every pound of fat while lean bulking, you’re doing a good job.

(Those with above-average genetics can gain slightly more muscle than fat, and those with below-average genetics may gain slightly more fat than muscle, but most people are in the middle.)

Want to know how many calories you should eat? Check out this article:

⇨ How Many Calories You Should Eat (with a Calculator)

4. Eat a high-protein and high-carb diet.

You’ve probably heard that a high-protein diet is best for building muscle.

This is true, and that’s why there’s so much talk about protein in bodybuilding circles.

Protein provides your body with the raw materials necessary for muscle building (amino acids), so if you don’t eat enough, you’ll struggle to gain muscle.

What is “enough,” though?

It’s quite a bit more than most people are used to eating (but not quite as much as some people claim).

Research shows that eating about 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight per day is ideal for muscle gain.

If you’re very overweight (25%+ body fat in men and 30%+ in women) or you want to do as little math as possible, then aim to get at least 40% of your daily calories from protein.

Either way, it comes out to around 30 to 40% of total daily calories for most people.

Now, while there’s little debate on the importance of eating adequate protein, carbs are another story.

Low-carb diets are a “thing” these days, but they really don’t deserve the hype.

They don’t help you lose fat faster, and they most definitely don’t help you gain muscle or strength faster, either.

To the contrary, eating plenty of carbs helps you gain muscle and strength faster in two ways:

- It increases whole-body glycogen levels, which improves workout performance and enhances genetic signaling related to muscle growth.

- It keeps insulin levels generally higher, which lowers muscle breakdown rates and creates a more anabolic environment in the body.

This is why several studies have shown that high-carb diets are superior for gaining muscle and strength than low-carb ones.

So, here’s the bottom line:

If you want to gain muscle as quickly as possible, then you want to eat more and not less carbs.

A good starting place is to get 30 to 50% of your total daily calories from carbs.

Want to know more about how much protein and carbs you should eat? Check out this article:

⇨ How to Make Meal Plans That Work For Any Diet

5. Take the right supplements.

I saved this for last because it’s the least important.

The truth is most supplements for building muscle and losing fat are worthless.

Unfortunately, no amount of pills and powders are going to make you muscular and lean.

That said, if you know how to diet and train properly, certain supplements can help accelerate the process. (And if you’d like to know exactly what supplements to take to reach your fitness goals, take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz.)

Here are the ones I use and recommend:

Whey+ Protein Powder

Whey protein powder is a staple in most athletes’ diets for good reason.

It’s digested quickly, it’s absorbed well, it has a fantastic amino acid profile, and it’s easy on the taste buds.

Not all whey proteins are created equal, though.

Whey concentrate protein powder, for example, can be as low as 30% protein by weight, and can also contain a considerable amount of fat and carbs.

And the more fat and carbs you’re drinking, the less you can actually enjoy in your food.

Whey isolate protein powder, on the other hand, is the purest whey protein you can buy. It’s 90%+ protein by weight and has almost no fat or carbs.

Another benefit of whey isolate is it contains no lactose, which means better digestibility and fewer upset stomachs.

Well, Whey+ is a 100% naturally sweetened and flavored whey isolate protein powder made from exceptionally high-quality milk from small dairy farms in Ireland.

It contains no GMOs, hormones, antibiotics, artificial food dyes, fillers, or other unnecessary junk, and it tastes delicious and mixes great.

So, if you want a clean, all-natural, and great tasting whey protein supplement that’s low in calories, carbs, and fat, you want to try Whey+ today.

Casein+ Protein Powder

Casein+ is 100% naturally sweetened and flavored casein isolate also made from milk sourced from small dairy farms in Ireland.

In contrast to whey, casein is digested very slowly, providing a steady stream of amino acids to the muscles for growth and repair, which some experts believe may make it a better choice for building muscle.

Whey, on the other hand, is digested faster and produces a more rapid rise in amino acid levels, which some experts think might enhance post-workout muscle growth.

Most evidence shows it’s a wash, though, and you won’t notice any difference in muscle growth between casein or whey so long as you eat enough protein every day.

Personally, I like to mix whey and casein together, as I prefer the flavor of whey and the creamy consistency of casein.

If I know that I’m going to need to go for several hours without food, then I typically choose Casein+, which keeps me full longer, too.

Pulse Pre-Workout

Is your pre-workout simply not working anymore?

Are you sick and tired of pre-workout drinks that make you sick and tired?

Have you had enough of upset stomachs, jitters, nausea, and the dreaded post-workout crash?

Do you wish your pre-workout supplement gave you sustained energy and more focus and motivation to train? Do you wish it gave you noticeably better workouts and helped you hit PRs?

If you’re nodding your head, then you’re going to love Pulse.

It increases energy, improves mood, sharpens mental focus, increases strength and endurance, and reduces fatigue . . . without unwanted side effects or the dreaded post-workout crash.

It’s also naturally sweetened and flavored and contains no artificial food dyes, fillers, or other unnecessary junk.

Lastly, it contains no proprietary blends and each serving delivers nearly 20 grams of active ingredients scientifically proven to improve performance.

Legion Protein Bars

Protein powders and mass gainers make it easier to hit your calorie and macronutrient goals, but you can’t beat the convenience of a protein bar.

The problem with most protein bars, though, is they taste like sugar-coated plywood and have the macros of a Snickers bar (too much fat and carbs and not enough protein).

That’s why I created a better protein bar—the Legion protein bar—which looks like this:

- 20 grams of high-quality protein

- Low in calories and sugar

- No gluten, fillers, or artificial sweeteners, flavors, dyes, or other chemical junk

- A delicious, real-food, “I-can’t-believe-it’s-not-candy” taste

- A fresh, moist mouthfeel that isn’t too hard or chewy

- Easy on your stomach (no cramping or bloating!)

In short, it’s everything I’ve wanted in a protein bar, and if you’re anything like me, you’re going to love them.

Not only do Legion protein bars taste amazing, they contain just 6 grams of fat, 5 grams of sugar, and 240 calories, which means they can fit into even the strictest of meal plans.

Atlas Mass Gainer

In an ideal world, we’d get all of our daily calories from carefully prepared, nutritionally balanced meals, and we’d have the time to sit down, slow down, and savor each and every bite.

In the real world, though, we’re usually rushing from one obligation to another and often forget to eat anything, let alone the optimal foods for building muscle, losing fat, and staying healthy.

That’s why meal replacement and “weight gainer” supplements and protein bars and snacks are more popular than ever.

Unfortunately, most contain low-quality protein powders and large amounts of simple sugars and unnecessary junk.

That’s why I created Atlas.

It’s a delicious “weight gainer” (meal replacement) supplement that provides you with 38 grams of high-quality protein per serving, along with 51 grams of nutritious, food-based carbohydrates, and just 6 grams of natural fats, as well as 26 micronutrients, enzymes, and probiotics that help you feel and perform your best.

Atlas is also 100% naturally sweetened and flavored as well, and contains no chemical dyes, cheap fillers, or other unnecessary junk.

Recharge Post-Workout Supplement

Recharge is a 100% natural post-workout supplement that helps you gain muscle and strength faster, and recover better from your workouts.

Once it’s had time to accumulate in your muscles (about a week of use), the first thing you’re going to notice is increased strength and anaerobic endurance, less muscle soreness, and faster post-workout muscle recovery.

And the harder you can train in your workouts and the faster you can recover from them, the more muscle and strength you’re going to build over time.

Furthermore, Recharge doesn’t need to be cycled, which means it’s safe for long-term use, and its effects don’t diminish over time.

It’s also naturally sweetened and flavored and contains no artificial food dyes, fillers, or other unnecessary junk.

Oh, and if you aren’t sure if the supplements discussed in this article are right for your budget, circumstances, and goals, then take the Legion Supplement Finder Quiz! In less than a minute, it’ll tell you exactly what supplements are right for you. Click here to check it out.

Summary: You don’t need supplements to get big and strong, but if your budget allows, you can get there faster with the right ones. Whey+ or Casein+ can help you hit your daily protein targets, Atlas can bolster your daily calorie intake, Recharge can help you gain muscle and strength faster, and Pulse can energize your workouts.

The Bottom Line on How Strong You Can Get Naturally

Predicting potential strength is difficult because it depends on a number of factors that can’t be perfectly quantified, including . . .

- Skill and attitude

- Bone length

- Muscle structure

- Muscle size

That said, a reliable method is comparing your strength on the squat, bench, and deadlift to other experienced lifters who are similar to you in size.

This is easier said than done, of course, which is why this article provides you with a calculator based on a robust dataset that’ll do the math for you.

You’ll also find a calculator based on the same data that allows you to compare your whole-body strength to someone else’s.

If you’re disappointed by your numbers, remember that you don’t need to get extremely strong to have a great physique—you just have to get much stronger than when you started. This will likely take several years, but keep at it and you’ll be thrilled with the final result.

So long as you do plenty of work on the squat, bench press, and deadlift, and so long as your technique is good, the general rule is to get stronger, you’re going to need to gain more muscle.

Although I don’t recommend them, steroids can help tremendously with both muscle and strength gain.

Steroids directly increase muscle growth and strength and greatly enhance recovery, which allows you to subject your body to a lot more training over time, thereby further boosting muscle and strength gain.

Lower reps and heavier weights (1 to 5 reps with 85 to 100% of one-rep max) maximize strength gains in the short term, and including higher reps and lighter weights (6 to 10 reps with 60 to 80% of one-rep max) in your routine maximizes muscle and thus strength gain over the long term.

So, to gain muscle and strength fast, you just need to follow these five principles:

- Do lots of heavy, compound strength training.

- Follow an effective strength training program.

- Eat slightly more calories than you burn.

- Eat a high-protein and high-carb diet.

- Take the right supplements.

Good luck!

***

This article is from the second edition of my bestselling fitness book for experienced weightlifters, Beyond Bigger Leaner Stronger, which is now live everywhere you can buy books online. Click here to learn more.

What’s your take on how strong you can get naturally? Have anything else you’d like to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Howarth, K. R., Phillips, S. M., MacDonald, M. J., Richards, D., Moreau, N. A., & Gibala, M. J. (2010). Effect of glycogen availability on human skeletal muscle protein turnover during exercise and recovery. Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(2), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00108.2009

- Denne, S. C., Liechty, E. A., Liu, Y. M., Brechtel, G., & Baron, A. D. (1991). Proteolysis in skeletal muscle and whole body in response to euglycemic hyperinsulinemia in normal adults. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism, 261(6 24-6). https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.6.e809

- Noakes, M., Foster, P. R., Keogh, J. B., James, A. P., Mamo, J. C., & Clifton, P. M. (2006). Comparison of isocaloric very low carbohydrate/high saturated fat and high carbohydrate/low saturated fat diets on body composition and cardiovascular risk. Nutrition and Metabolism, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-3-7

- Creer, A., Gallagher, P., Slivka, D., Jemiolo, B., Fink, W., & Trappe, S. (2005). Influence of muscle glycogen availability on ERK1/2 and Akt signaling after resistance exercise in human skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology, 99(3), 950–956. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00110.2005

- Burke, L. M., Kiens, B., & Ivy, J. L. (2004). Carbohydrates and fat for training and recovery. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264041031000140527

- Johnston, C. S., Tjonn, S. L., Swan, P. D., White, A., Hutchins, H., & Sears, B. (2006). Ketogenic low-carbohydrate diets have no metabolic advantage over nonketogenic low-carbohydrate diets. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(5), 1055–1061. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1055

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. In Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 1–20). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Tipton, K. D., & Ferrando, A. A. (2008). Improving muscle mass: Response of muscle metabolism to exercise, nutrition and anabolic agents. Essays in Biochemistry, 44, 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSE0440085

- Wang, X., Hu, Z., Hu, J., Du, J., & Mitch, W. E. (2006). Insulin resistance accelerates muscle protein degradation: Activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by defects in muscle cell signaling. Endocrinology, 147(9), 4160–4168. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2006-0251

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. In Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 1–20). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Damas, F., Phillips, S. M., Libardi, C. A., Vechin, F. C., Lixandrão, M. E., Jannig, P. R., Costa, L. A. R., Bacurau, A. V., Snijders, T., Parise, G., Tricoli, V., Roschel, H., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2016). Resistance training-induced changes in integrated myofibrillar protein synthesis are related to hypertrophy only after attenuation of muscle damage. Journal of Physiology, 594(18), 5209–5222. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP272472

- Bhasin, S., Storer, T. W., Berman, N., Callegari, C., Clevenger, B., Phillips, J., Bunnell, T. J., Tricker, R., Shirazi, A., & Casaburi, R. (1996). The Effects of Supraphysiologic Doses of Testosterone on Muscle Size and Strength in Normal Men. New England Journal of Medicine, 335(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199607043350101

- Fry, A. C., Webber, J. M., Weiss, L. W., Harber, M. P., Vaczi, M., & Pattison, N. A. (2003). Muscle fiber characteristics of competitive power lifters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 17(2), 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1519/1533-4287(2003)017<0402:MFCOCP>2.0.CO;2

- Bottinelli, R., Canepari, M., Pellegrino, M. A., & Reggiani, C. (1996). Force-velocity properties of human skeletal muscle fibres: Myosin heavy chain isoform and temperature dependence. Journal of Physiology, 495(2), 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021617

- Jandacka, D., & Uchytil, J. (2011). Optimal load maximizes the mean mechanical power output during upper extremity exercise in highly trained soccer players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(10), 2764–2772. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31820dbc6d

- Scott, W., Stevens, J., & Binder-Macleod, S. A. (2001). Human skeletal muscle fiber type classifications. In Physical Therapy (Vol. 81, Issue 11, pp. 1810–1816). American Physical Therapy Association. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/81.11.1810

- Alvar, B., Wenner, R., & Dodd, D. J. (2010). The Effect Of Daily Undulated Periodization As Compared To Linear Periodization In Strength Gains Of Collegiate Athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24, 1. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jsc.0000366980.24709.0d

- Erskine, R. M., Jones, D. A., Williams, A. G., Stewart, C. E., & Degens, H. (2010). Inter-individual variability in the adaptation of human muscle specific tension to progressive resistance training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(6), 1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1601-9

- Wernbom, M., Augustsson, J., & Thomeé, R. (2007). The influence of frequency, intensity, volume and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans. In Sports Medicine (Vol. 37, Issue 3, pp. 225–264). Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737030-00004

- Keogh, J. W. L., Hume, P. A., Pearson, S. N., & Mellow, P. (2007). Anthropometric dimensions of male powerlifters of varying body mass. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(12), 1365–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410601059630

- Brechue, W. F., & Abe, T. (2002). The role of FFM accumulation and skeletal muscle architecture in powerlifting performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 86(4), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-001-0543-7

- Delp, S. L., & Maloney, W. (1993). Effects of hip center location on the moment-generating capacity of the muscles. Journal of Biomechanics, 26(4–5), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(93)90011-3

- Trezise, J., Collier, N., & Blazevich, A. J. (2016). Anatomical and neuromuscular variables strongly predict maximum knee extension torque in healthy men. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 116(6), 1159–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-016-3352-8

- Erskine, R. M., Jones, D. A., Williams, A. G., Stewart, C. E., & Degens, H. (2010). Inter-individual variability in the adaptation of human muscle specific tension to progressive resistance training. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 110(6), 1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-010-1601-9

- VANDERBURGH PAUL M. (n.d.). A simple index to adjust maximal strength measures by body mass. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://www.asep.org/asep/asep/Vander.html

- NUCKOLS GREG. (n.d.). Who’s The Most Impressive Powerlifter? • Stronger by Science. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://www.strongerbyscience.com/whos-the-most-impressive-powerlifter/

- Niklas, K. J., & Kutschera, U. (2015). Kleiber’s law: How the fire of life ignited debate, fueled theory, and neglected plants as model organisms. Plant Signaling and Behavior, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2015.1036216

- Dandoy, C., & Gereige, R. S. (2012). Performance-enhancing drugs. In Pediatrics in Review (Vol. 33, Issue 6, pp. 265–272). American Academy of Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.33-6-265