Key Takeaways

- The Mediterranean diet involves eating a lot of whole grains, olive oil, fruits, vegetables, some seafood, legumes, and dairy, and very little red meat, saturated fat, sugar, and processed food.

- Research shows that the Mediterranean diet helps reduce the risk of heart disease, type ll diabetes, cancer, and cognitive decline, but it’s not ideal for weight loss.

- Although there’s nothing wrong with following a traditional Mediterranean diet, you can likely get all of the benefits by following a more flexible high-protein, plant-centric diet.

In the early 1960s, a scientist named Ancel Keys was puzzling over a question:

Why were rich, middle-aged businessmen in Minnesota more likely to die of heart disease than poor villagers in Italy?

Up to this point, most scientists considered heart disease to be part and parcel of the aging process—a result of your decaying DNA rather than your diet or exercise habits.

But then there were these remote villages in Southern Italy that had the highest rates of centenarians in the world and some of the lowest rates of heart disease, despite being populated with people genetically similar to American men.

Data like this convinced Keys that heart disease might be preventable, and was bolstered by other findings.

For instance, Keys discovered that in food-starved regions of post-war Europe, cardiovascular disease dropped along with the food supply, implying a connection between the two seemingly unrelated circumstances.

As the evidence mounted, Keys became more convinced that diet was a key factor in the risk of heart disease, and to test his hypothesis, he conducted an enormous study—one that would become his magnum opus.

Starting in 1958, the Seven Countries Study gathered data from 12,763 men from Finland, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Japan, and the United States and Netherlands.

The goal was to analyze the diets and rates of heart disease and death among men from very different regions.

While the most popularized finding was a correlation between saturated fat intake and cholesterol levels and heart disease, another important discovery was the low incidence of heart disease and early death among people following what became known as the “Mediterranean diet.”

Specifically, these especially heart-healthy people ate less saturated fat and cholesterol, and more fruits, vegetables, legumes, seafood, and olive oil than their least healthy counterparts around the world.

Interest in this diet was boosted by several bestselling books Keys and his wife published in the 1970s including How to Eat Well and Stay Well the Mediterranean Way and The Benevolent Bean.

In a fitting testament to his life’s work, Keys died in 2004 at 101 years old.

His legacy, however, lives on—The Seven Countries Study is still ongoing, and the Mediterranean diet has become the basis for the Food Pyramid in the United States and most official dietary recommendations around the world.

Proponents of the diet claim it can minimize the risk of a whole host of illnesses and ailments, including . . .

- Heart disease, stroke, and atherosclerosis

- High blood pressure

- High blood sugar

- Obesity

- Type ll diabetes

- And others

Like everything related to nutrition and fitness, however, the Mediterranean diet isn’t without critics.

Some of the common claims leveled against Keys’ work include . . .

- The methods used to collect data for the Seven Countries Study were biased and so the results can’t be trusted.

- The Mediterranean diet offers no unique benefits that can’t be obtained from other types of diets.

- The Mediterranean diet contributes to diabetes due to the large amount of carbs like pasta, bread, and grains.

Who’s right?

The short story is that the Mediterranean diet is popular among scientists, doctors, and the average dieter for a reason: it’s a perfectly healthy way to eat.

That said, it’s not for everyone and not the only way to eat well.

Let’s find out why.

Table of Contents

+

Want to listen to more stuff like this? Check out my podcast!

What Is the Mediterranean Diet?

The Mediterranean diet is based on how people in several countries in the Mediterranean Basin eat, particularly Italy and Greece.

Keys gathered data from both of these countries for the Seven Countries Study, and found that their diets largely revolved around whole grains, olive oil, and wine, with varying amounts and types of seafood, beans, fruits, and vegetables.

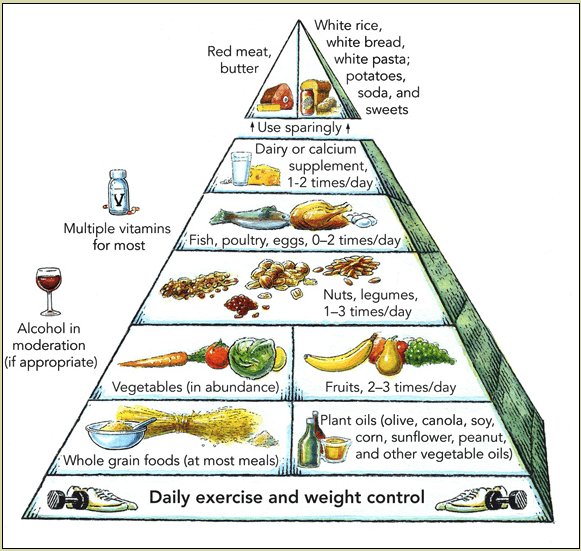

In 1993, the Harvard School of Public Health and a nonprofit organization called Oldways endorsed Keys’ work by publishing a Mediterranean-style food pyramid:

As you can see, the Mediterranean diet involves eating a lot of . . .

- Fish like salmon, sardines, mackerel, tilapia, cod, etc.

- Fresh and cooked vegetables like bell peppers, cucumbers, leafy greens, carrots, etc.

- Whole grains such as barley, oats, quinoa, and whole grain bread

- Legumes such as chickpeas, lentils, and kidney, black, and pinto beans

- Nuts like almonds, cashews, pistachios, and walnuts

- Seeds like flax, sesame, and pumpkin

- Fresh fruits like strawberries, apples, grapes, oranges, cherries, and berries

- Olive oil and other sources of monounsaturated fats like olives and avocado

- Herbs and spices like garlic, oregano, basil, rosemary, sage, mint, etc.

Eating some . . .

- Poultry

- Eggs

- Cheese

- Yogurt

- Wine

- Coffee and tea (if you want)

And eating very little . . .

- Processed meat like bacon, sausage, and prosciutto

- Red meat of any kind

- Sugary drinks and desserts

- Refined grains like breakfast cereal, energy bars, and pastries

- Trans fat of any kind

Another important factor stressed by most Mediterranean dieters is savoring your food with friends and family without technological distractions like smartphones, TV, and computers. In other words, eating “mindfully.”

“Mindful eating” might sound a bit woo-woo to you, but it was a common denominator among all of the cultures that enjoyed long lives and robust health into old age in the Seven Countries Study.

Furthermore, studies show that taking the time to focus on and savor your meals while eating them—especially with family—can help people subconsciously eat less, decreases stress, and reduces the risk of unhealthy behaviors like smoking, drug use, and promiscuity.

Most proponents of the Mediterranean diet also emphasize the importance of portion control, another common practice among the different cultures analyzed in the Seven Countries Study.

For example, in Japan the people had a tradition of eating until satisfied, but not overly full, and many of the other countries followed similar rules of thumb.

There are no official macronutrient guidelines for the Mediterranean diet, but most of the time it works out to something like this:

- High-carb (40 to 60% of calories)

- Moderate fat (20 to 40% of calories)

- Low protein (~10 to 20% of calories)

The Mediterranean diet is also often promoted as a weight loss diet, and while many people do lose weight with it in the beginning, it’s usually not a viable long-term weight loss strategy (more on this soon).

Why Do People Follow the Mediterranean Diet?

The primary reason people follow the Mediterranean diet goes back to its origin story—reducing the risk of heart disease.

And studies show it can do just that and more, including reducing the risk of cancer, diabetes, and dementia.

During the obesity surge of the 90’s, the Mediterranean diet also gained buzz as an effective weight loss protocol.

At bottom, though, the Mediterranean diet has become synonymous with “heart health,” so let’s start by looking at its relationship with heart disease.

Can the Mediterranean Diet Prevent Heart Disease?

To answer this question, let’s start by reviewing the findings of the study that started it all: the Seven Countries Study.

This seminal research showed that . . .

- There was a correlation between cholesterol levels in the blood and the risk of heart disease over the next 5 to 40 years.

- Increased blood pressure was correlated with an increased risk of heart disease and stroke.

- Cardiovascular disease was closely linked with overall mortality (most people were dying from some form of heart or blood vessel disease).

- People with risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as increased cholesterol, are also at an increased risk of dementia and other brain disorders later in life.

- People in the United States and Northern Europe had much higher rates of cardiovascular disease than people from Southern Europe and Japan.

As you can imagine, these discoveries sparked a heated scientific debate—one that still rages today.

To understand why, you first have to realize how little we knew about nutrition and health when this study was conducted.

While we take it for granted that there’s a connection between diet and long-term health, that was a controversial theory in the late 1950s.

People generally ate what they could afford, preferred, and had access to, and didn’t give much thought to potential long-term ramifications of their dietary habits.

Keys correctly suspected that what we eat does significantly impact our health and wellness, and this led him to conduct the Seven Countries Study—the first multi-country study on nutrition and health ever conducted, the largest to look at the link between diet and heart disease, and still one of the longest running studies of human health in the world.

And despite what some people say, Keys was no scientific slouch, either.

For instance, he invented the K ration, one of the earliest versions of a Meal Ready-to-Eat (MRE) used by all branches of the armed forces during World War ll, he conducted the most extreme study of human metabolism ever with the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, and he oversaw some of the earliest experiments on how the human body responded to changes in altitude.

Thanks to Keys’ bona fides and the impressive scope and rigor of the Seven Countries Study, its conclusions made quite a splash in the scientific community.

Many experts at the time speculated that the association between dietary cholesterol intake and blood levels of cholesterol was likely causative, and formulated what became known as the “diet-heart hypothesis.”

This theory more or less boils down to:

- Cholesterol in the blood causes heart disease.

- Eating dietary cholesterol raises levels of cholesterol in the blood.

- To avoid heart disease, people should avoid foods high in cholesterol, like saturated fat.

This was a perfectly reasonable idea—one that Keys got behind as well—and it soon became official policy by many countries, including the United States.

We now know the true relationship between dietary fat intake and heart disease is more nuanced than that, however.

For example, Keys was correct in that there is a connection between cholesterol levels in the blood and heart disease, but in most people, eating cholesterol and saturated fat doesn’t usually raise blood levels of cholesterol or increase the risk of heart disease.

Ever since Keys first published his data, a long list of scientists have seized on such discrepancies to dismiss Keys as a fraud and his crusade against dietary fat as a ploy for personal enrichment.

The loudest of his detractors are the new breed of high-fat diet gurus, such as Gary Taubes, who claim Keys and his research are the epitome of everything that’s wrong with nutrition science.

Such allegations are ridiculous.

Yes, the Seven Countries Study was imperfect and Keys did oversell some of its conclusions, but it was more right than wrong. Keys even acknowledged as much when he was interviewed in 1961 for the Time Magazine article that made him famous.

At bottom, however, Keys’ take-home advice was to “. . . eat less fat meat, fewer eggs and dairy products. Spend more time on fish, chicken, calves’ liver, Canadian bacon, Italian food, Chinese food, supplemented by fresh fruits, vegetables and casseroles. Nobody wants to live on mush. But reasonably low-fat diets can provide infinite variety and aesthetic satisfaction for the most fastidious—if not the most gluttonous—among us.”

In other words, he was recommending a fairly balanced, mostly plant-based diet with more fish than meat and more monounsaturated fat than saturated fat—hardly a recipe for a highly marketable fad diet that can pave the way to fame and fortune.

The most common criticism of Keys’ work is that he cherry picked the data for his Seven Countries Study. Specifically, it’s often claimed he originally gathered data from 22 countries but only chose to use data from 7 that aligned with his initial assumptions.

It’s true that Keys didn‘t include all of the data in the final results, but it’s disingenuous to say it was due to foul play.

It’s not only common but necessary for researchers to exclude some data from their study results because there are often good reasons to do so.

For example, Keys excluded some countries because their diets deviated too much from the Mediterranean diet, which would have made it difficult to study the effects of their particular style of eating.

He excluded France as well, which has generated considerable controversy due to what’s now known as the “French Paradox.”

In short, the French had low rates of heart disease despite eating large amounts of saturated fat, so why did Keys exclude them?

Well, this wasn’t discovered until decades after the Seven Countries Study began, so it’s more likely Keys excluded the data on the French because he wasn’t able to gather enough reliable information on their eating habits, not due to a bias against high-fat diets.

Moreover, as journalist Denise Minger points out, even when you include all the data Keys excluded, there’s still a significant correlation between fat intake and heart disease.

Perhaps the strongest counterargument to Keys’ research is this:

Many countries did a sloppy job of accurately identifying and recording causes of death, and this made heart disease seem more prevalent than it really was. For example, someone could die of a brain aneurysm yet, due to negligence, incompetence, or technological deficiency, the physician would ascribe their death to just “heart disease.”

To explore the ramifications of this, scientists in the 1950s removed all of the deaths supposedly linked to heart disease from Keys’ data and reanalyzed it.

This produced almost the exact opposite results of the original study. Now, the people who consumed the most fat, animal fat, and animal products had the lowest risk of dying from all causes. Additionally, the people who ate the most carbs also lived the shortest lives.

Some people point to these findings as proof that eating an abundance of dietary fat, including saturated fat, is healthy and carbs are detrimental, but that’s not what the researchers concluded.

A more likely explanation for this observation, they explained, is that people who eat more animal products also tend to be more affluent and live in more developed areas, which affords them greater access to high-quality medical care and education as well as a safer environment.

In other words, these people were living longer in spite of their diets not because of them.

So, what are you supposed to make of all this? Does the Mediterranean diet actually reduce the risk of heart disease?

The truth is we don’t really know.

The Seven Countries Study is observational research, meaning it follows a bunch of people for a period of time and records what they eat and do and how their health changes.

Such research is used to tease out correlations (associations) but can never establish causations. In other words, observational research can be used to say “it appears there may be a connection here” but not “this causes that.”

To establish causation, scientists must perform rigorous experiments that allow them to isolate and control important factors.

Dozens of these types of studies have been conducted on Mediterranean-ish diets and heart disease since the publication of the Seven Countries Study, including several in-depth meta-analyses (studies of studies).

In one meta-analysis, scientists from Warwick Medical School examined data from 11 studies that included 52,000 participants. They included studies that involved one group following a diet that met at least two of these seven criteria . . .

- High intake of monounsaturated fat

- Low to moderate intake of red wine

- High intake of legumes

- High intake of cereals and grains

- High intake of fruits and vegetables

- Low intake of meat and dairy products and/or high intake of seafood

- Low to moderate intake of dairy products

. . . and one group that ate a standard Western diet which was more or less the mirror opposite of the above criteria.

After looking at a number of potential risk factors for heart disease and actual cardiovascular events (heart attacks, strokes, etc.), the researchers found that people following the Mediterranean-ish diets experienced a slight drop in their total and LDL cholesterol levels, but no difference in cardiovascular events.

As a result, the scientists concluded that “ . . . limited evidence to date suggests some favourable effects on cardiovascular risk factors,” but that more evidence was needed to prove this was the case.

Several other meta-analyses have come to the same conclusion: The Mediterranean diet may help reduce the risk of heart disease, but if it does, it’s not by much.

This position was strengthened in 2018 when the authors of a popular study used to promote the Mediterranean diet as cardioprotective were forced to admit they’d bungled their analysis, and the benefits were less significant than they’d originally reported.

So, taken as a whole, the weight of the evidence indicates a Mediterranean-type diet is more “heart-healthy” than how most Western people eat, but that begs a question:

What about the Mediterranean diet most accounts for this? Are certain elements more impactful than others?

For example, the traditional Mediterranean diet involves heavily restricting your intake of red meat, eggs, and dairy, but such recommendations are hard to square with the findings of other studies showing . . .

- High-cholesterol foods like eggs have been more or less exonerated from heart disease.

- Processed meats may increase the risk of disease, but there’s little evidence that red meat per se increases the risk of heart disease.

- Dairy is generally considered healthy and more likely to prevent disease than contribute to it.

So, can you get the health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet while still consuming plenty of red meat, dairy, and poultry?

Can you omit certain portions of the diet without drawbacks, such as nuts, wine, and bread?

Can you improve your health and wellbeing just as much by eating more foods high in monounsaturated fats, fiber, and micronutrients and fewer processed foods in general?

Based on decades of research, the most scientifically accurate answer to each of these questions is “probably.”

When it comes to preventing heart disease, the most effective recipe appears to be:

- Stay active

- Don’t smoke

- Don’t get fat (by managing your energy balance responsibly)

- Eat lots of fresh fruits and vegetables

- Eat plenty of monounsaturated and some polyunsaturated fats

- Eat moderate amounts of saturated fat (less than 10% of total calories)

- Get most of your calories from whole, minimally processed, nutrient-dense foods

Do those seven things and you’ll bring your risk of heart disease to about as low as it can possibly go.

I’d also like to punch up the importance of staying active because most people tend to fixate on diet in relation to health but pay little attention to the effects of exercise.

In the case of heart health, research shows physical activity is a more reliable protector against heart disease than switching to a different diet or avoiding certain foods.

Simply put, if you’re sedentary, and especially if you’re sedentary and overweight, you’re going to have a significantly increased risk of heart disease regardless of what you do or don’t eat.

Drizzling more olive oil on your whole-grain bread or swapping salmon for steak isn’t going to help you nearly as much as working out a few times per week.

The bottom line is the Mediterranean diet can reduce your risk of heart disease, but other, less restrictive dietary strategies can have the same benefits as well.

Can the Mediterranean Diet Prevent Type ll Diabetes?

Type ll diabetes is a disease in which the body isn’t able to properly manage glucose levels.

Typically, it’s the result of overeating and becoming overweight, which impairs the body’s ability to absorb glucose from the blood.

As a result, people with type ll diabetes have chronically high glucose levels, which can damage nerves, blood vessels, and cells throughout the body.

One of the most common dietary recommendations for managing type ll diabetes is to eat less carbohydrate. Type ll diabetes is a disease of excess glucose, after all, so reducing carb intake should reduce glucose in the blood as well, resulting in fewer symptoms.

The Mediterranean diet is generally high-carb, so it would seem to be poorly suited to people with type ll diabetes.

Interestingly, research shows otherwise.

A good example of this comes from a meta-analysis conducted by scientists at the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry.

The researchers scrutinized 20 studies on people with type ll diabetes that involved the comparison of low-carb, vegetarian, vegan, low-glycemic index, high-fiber, high-protein, and Mediterranean-style diets with low-fat, high-glycemic index, low-protein, and several other types of diets recommended for diabetics.

Surprisingly, the scientists found that people following the (high-carb) Mediterranean diet, low-carb diet, low-glycemic index diet, and high-protein diet all experienced a reduction in their average blood glucose levels, with the group following the Mediterranean diet doing the best by a small margin.

The people following the Mediterranean diet also experienced the greatest drop in blood pressure, the most weight loss, and the biggest improvement in HDL cholesterol.

Another study supporting the benefits of the Mediterranean diet for diabetics was conducted by scientists at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

In this study, the researchers split 322 middle-aged obese men and women into one of three groups:

- Group one followed a calorie-restricted low-fat diet.

- Group two followed a calorie-restricted Mediterranean diet.

- Group three followed an unrestricted low-carb diet (The Atkins Diet).

After two years, the researchers measured how much weight the participants lost and noted any changes in cholesterol levels and symptoms of diabetes.

Once again, the Mediterranean diet improved glucose levels more than the low-carb diet (and helped the participants lose just as much weight).

These results are supported by other studies showing that the Mediterranean diet can reduce markers of diabetes, and that eating less fruit (and thus carbs) doesn’t improve the symptoms of diabetes.

What’s going on here? How can blood glucose levels improve so markedly in people eating a lot of carbs?

The simple answer is that managing type ll diabetes involves a lot more than depriving your body of glucose.

For one thing, the Mediterranean diet generally includes a lot of fiber from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and research shows that eating enough fiber can significantly improve insulin sensitivity.

Insulin is a hormone that shuttles glucose out of the blood and into cells, and when your cells become less responsive to its effects, glucose builds up in the blood.

Thus, insulin resistance (insensitivity) is one of the main symptoms of type ll diabetes, and improving insulin sensitivity is equally if not more important for fighting the disease than reducing your carb intake.

There are a number of ways to effectively increase insulin sensitivity and thus deal with type II diabetes.

Many studies have shown that exercise is one of the best ways to do this, and that it can also significantly reduce the amount of glucose in the blood.

Another highly effective way to increase insulin sensitivity is to lose weight (if you’re overweight). Simply put, the closer you are to a healthy body weight, the better your cells will respond to insulin.

Weight loss is so significant in this regard that many researchers believe it’s the primary reason the Mediterranean diet resulted in a reduction of type ll diabetes symptoms—in most of the studies demonstrating these benefits, the participants were overweight and lost weight.

The bottom line is that the Mediterranean diet can improve symptoms of and protect against type ll diabetes by providing adequate fiber and aiding in weight loss, both of which improve insulin sensitivity.

Can the Mediterranean Diet Help You Lose Weight?

Yes.

Like any type of healthy diet, the Mediterranean diet can help you lose weight by helping you eat fewer calories than you burn.

This is particularly true if you’re switching from a standard Western diet with lots of processed, high-calorie junk food.

If, however, the Mediterranean diet doesn’t result in a calorie deficit, you won’t lose weight. And the same goes for every other diet out there, including the paleo diet, ketogenic diet, carnivore diet, vegan diet, detox diets, and every other regimen you can think of.

With that out of the way, the real question becomes “Is the Mediterranean diet ideal for weight loss?”

Probably not.

Overall, the Mediterranean diet has a lot going for it. It’s high in fiber and fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other minimally processed foods, which are more satiating than average Western fare.

In this way, the Mediterranean diet makes it easier to feel full and satisfied on fewer calories, which makes it easier to lose weight.

The major downside of the Mediterranean diet is it’s pitifully low in protein, and for me, this is a weight loss deal breaker.

For example, in one study on the Mediterranean diet, participants consumed just 18% of their total calories from protein, or about 80 grams per day.

Another study on the Mediterranean diet had participants get just 14% of their daily calories from protein, which worked out to 70 grams per day.

In both cases, the participants in these studies were eating about 0.4 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day.

This is suboptimal because most research shows you want to eat closer to 0.8 to 1.2 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day to lose as much fat and little muscle as possible, or about 2 to 3 times as much as you’ll get on a standard Mediterranean diet.

The bottom line is study after study has confirmed that high-protein dieting is superior to low-protein dieting in just about every meaningful way, and especially in the context of weight loss.

Specifically, research shows people who eat more protein:

- Lose fat faster

- Gain more muscle

- Burn more calories

- Experience less hunger

- Have stronger bones

- Generally enjoy better moods

And protein intake is even more important when you exercise regularly because this increases your body’s demand for amino acids (which are provided by protein).

Eating adequate protein is also vital for preserving lean mass while dieting, which is just as important losing fat. If you lose too much muscle while losing weight, you’ll wind up skinny fat.

Protein intake is important among sedentary folk as well. Studies show that such people lose muscle faster as they age if they don’t eat enough protein, and the faster they lose muscle, the more likely they are to die from all causes.

So, in some respects, the Mediterranean diet is an ideal weight loss diet—what with its emphasis on whole, filling foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains—but it fails to check one of the most important boxes: protein intake.

The bottom line is that the Mediterranean diet can help you lose weight, but it’ll help a whole lot more if you eat significantly more protein than what’s typically recommended.

Can the Mediterranean Diet Help You Live Longer?

The Seven Countries Study produced a number of interesting observations.

One was that people who followed a Mediterranean style diet tended to have a slightly lower risk of heart disease.

As the study went on, it also became apparent that people who followed the Mediterranean diet also tended to have a lower risk of dying from just about everything, including cancer, dementia, Alzheimer’s, and several other chronic diseases.

Newer, more rigorous studies also support these findings.

For example, a 2018 meta-analysis conducted by scientists at the University of Florence involving nearly 13 million participants across 29 studies found that people following the Mediterranean diet had a significantly lower risk of death than people who followed other diets.

An earlier meta-analysis published in 2008 conducted by the same lab found that people who followed the Mediterranean diet had a 6% lower risk of dying from cancer.

And finally, a 2013 systematic review of 12 studies conducted by scientists at the University of Exeter found that people who followed a Mediterranean diet experienced better cognitive function in old age.

Feathers in the cap, for sure, but there’s a caveat: most of the data reviewed was observational, meaning we can’t know for sure whether the Mediterranean diet was increasing longevity or something else.

We also don’t know whether the Mediterranean diet is superior or even as good as other similar diets, such as a high-protein, mostly plant-based, higher carb and lower fat “bodybuilding” diet.

For instance, we know that simply increasing fruit, vegetable, and fiber intake and reducing alcohol consumption drastically reduces the risk of cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease—most of the leading causes of death in developed countries.

The bottom line is that the Mediterranean diet probably does help people live longer and healthier lives, but you don’t necessarily need to follow it exactly to get the same results.

The Bottom Line on the Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet involves eating a lot of whole grains, olive oil, fruits, vegetables, some seafood, legumes, and dairy, and very little red meat, saturated fat, sugar, and processed food.

The primary reason people follow the Mediterranean diet is to reduce their risk of heart disease.

While the Mediterranean diet can reduce the risk of heart disease, its effectiveness in this regard has likely been overblown by health authorities, doctors, and wellness gurus.

Furthermore, research suggests its cardioprotective properties have more to do with weight loss and eating more fruits and vegetables and less saturated fat than anything else.

Speaking of weight loss, the Mediterranean diet can help you lose weight if you’re switching from an average Western diet, but it’s not ideal for this purpose because it’s generally low in protein.

Studies show people who follow the Mediterranean diet do generally live longer, healthier lives, but so do people who follow more flexible dietary guidelines like eating plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, and some whole grains, meat, seafood, poultry, dairy, nuts, and seeds, and not too much saturated fat, sugar, and other processed foods.

So, in the final analysis, if the Mediterranean diet is appealing to you, follow it. I’d recommend adding in a bit more protein, however, and especially if you’re physically active.

If, however, the Mediterranean diet doesn’t float your boat, you can do just as well with the diet I just described above. And especially if you’re physically active. 🙂

If you’re interested in learning more about how to eat to get and stay healthy, feel great, and stay lean and strong, check out this article:

The Definitive Guide to Effective Meal Planning

What’s your take on the Mediterranean diet? Have anything else to share? Let me know in the comments below!

Scientific References +

- Hughes, T. F., Andel, R., Small, B. J., Borenstein, A. R., Mortimer, J. A., Wolk, A., Johansson, B., Fratiglioni, L., Pedersen, N. L., & Gatz, M. (2010). Midlife fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of dementia in later life in swedish twins. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(5), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c65250

- Chen, G. C., Lv, D. B., Pang, Z., Dong, J. Y., & Liu, Q. F. (2013). Dietary fiber intake and stroke risk: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(1), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2012.158

- Key, T. J. (2011). Fruit and vegetables and cancer risk. In British Journal of Cancer (Vol. 104, Issue 1, pp. 6–11). Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6606032

- Lourida, I., Soni, M., Thompson-Coon, J., Purandare, N., Lang, I. A., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Llewellyn, D. J. (2013). Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: A systematic review. Epidemiology, 24(4), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182944410

- Sofi, F., Cesari, F., Abbate, R., Gensini, G. F., & Casini, A. (2008). Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: Meta-analysis. BMJ, 337(7671), 673–675. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1344

- Dinu, M., Pagliai, G., Casini, A., & Sofi, F. (2018). Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. In European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 72, Issue 1, pp. 30–43). Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2017.58

- Brown, J. C., Harhay, M. O., & Harhay, M. N. (2016). Sarcopenia and mortality among a population-based sample of community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 7(3), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12073

- Metter, E. J., Talbot, L. A., Schrager, M., & Conwit, R. (2002). Skeletal muscle strength as a predictor of all-cause mortality in healthy men. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 57(10), B359–B365. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/57.10.B359

- Krieger, J. W., Sitren, H. S., Daniels, M. J., & Langkamp-Henken, B. (2006). Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: A meta-regression. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(2), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.2.260

- Phillips, S. M., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(SUPPL. 1). https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.619204

- Paddon-Jones, D., Westman, E., Mattes, R. D., Wolfe, R. R., Astrup, A., & Westerterp-Plantenga, M. (2008). Protein, weight management, and satiety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(5). https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1558s

- Westerterp, K. R. (2004). Diet induced thermogenesis. In Nutrition and Metabolism (Vol. 1, Issue 1). Nutr Metab (Lond). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-1-5

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. In Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 1–20). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Evans, E. M., Mojtahedi, M. C., Thorpe, M. P., Valentine, R. J., Kris-Etherton, P. M., & Layman, D. K. (2012). Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: A randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutrition and Metabolism, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-55

- Astrup, A., Raben, A., & Geiker, N. (2015). The role of higher protein diets in weight control and obesity-related comorbidities. In International Journal of Obesity (Vol. 39, Issue 5, pp. 721–726). Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.216

- Campos-Nonato, I., Hernandez, L., & Barquera, S. (2017). Effect of a High-Protein Diet versus Standard-Protein Diet on Weight Loss and Biomarkers of Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Obesity Facts, 10(3), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1159/000471485

- Helms, E. R., Zinn, C., Rowlands, D. S., Naidoo, R., & Cronin, J. (2015). High-protein, low-fat, short-term diet results in less stress and fatigue than moderate-protein, moderate-fat diet during weight loss in male weightlifters: A pilot study. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 25(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0056

- Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Nutrition and supplementation. In Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Vol. 11, Issue 1, pp. 1–20). BioMed Central Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Esposito, K., Marfella, R., Ciotola, M., Di Palo, C., Giugliano, F., Giugliano, G., D’Armiento, M., D’Andrea, F., & Giugliano, D. (2004). Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292(12), 1440–1446. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.12.1440

- Cioffi, I., Ibrugger, S., Bache, J., Thomassen, M. T., Contaldo, F., Pasanisi, F., & Kristensen, M. (2016). Effects on satiation, satiety and food intake of wholegrain and refined grain pasta. Appetite, 107, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.08.002

- Knudsen, S. H., Karstoft, K., Pedersen, B. K., Van Hall, G., & Solomon, T. P. J. (2014). The immediate effects of a single bout of aerobic exercise on oral glucose tolerance across the glucose tolerance continuum. Physiological Reports, 2(8), 12114. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.12114

- Clamp, L. D., Hume, D. J., Lambert, E. V., & Kroff, J. (2017). Enhanced insulin sensitivity in successful, long-term weight loss maintainers compared with matched controls with no weight loss history. Nutrition & Diabetes, 7(6), e282. https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2017.31

- Borghouts, L. B., & Keizer, H. A. (2000). Exercise and insulin sensitivity: A review. In International Journal of Sports Medicine (Vol. 21, Issue 1, pp. 1–12). Int J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2000-8847

- Georgoulis, M., Kontogianni, M. D., & Yiannakouris, N. (2014). Mediterranean diet and diabetes: Prevention and treatment. Nutrients, 6(4), 1406–1423. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6041406

- Christensen, A. S., Viggers, L., Hasselström, K., & Gregersen, S. (2013). Effect of fruit restriction on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes--a randomized trial. Nutrition Journal, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-29

- Dinu, M., Pagliai, G., Casini, A., & Sofi, F. (2018). Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. In European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 72, Issue 1, pp. 30–43). Nature Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2017.58

- Shai, I., Schwarzfuchs, D., Henkin, Y., Shahar, D. R., Witkow, S., Greenberg, I., Golan, R., Fraser, D., Bolotin, A., Vardi, H., Tangi-Rozental, O., Zuk-Ramot, R., Sarusi, B., Brickner, D., Schwartz, Z., Sheiner, E., Marko, R., Katorza, E., Thiery, J., … Stampfer, M. J. (2008). Weight Loss with a Low-Carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or Low-Fat Diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa0708681

- Ajala, O., English, P., & Pinkney, J. (2013). Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes1-3. In American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 97, Issue 3, pp. 505–516). Am J Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.042457

- Olokoba, A. B., Obateru, O. A., & Olokoba, L. B. (2012). Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review of current trends. In Oman Medical Journal (Vol. 27, Issue 4, pp. 269–273). Oman Medical Specialty Board. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2012.68

- Shiroma, E. J., & Lee, I. M. (2010). Physical activity and cardiovascular health: Lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, Gender, and race/ethnicity. In Circulation (Vol. 122, Issue 7, pp. 743–752). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914721

- Carnethon, M. R. (2009). Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Disease: How Much Is Enough? American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 3(1_suppl), 44S-49S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827609332737

- Winzer, E. B., Woitek, F., & Linke, A. (2018). Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of coronary artery disease. In Journal of the American Heart Association (Vol. 7, Issue 4). American Heart Association Inc. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.007725

- Anand, S. S., Hawkes, C., De Souza, R. J., Mente, A., Dehghan, M., Nugent, R., Zulyniak, M. A., Weis, T., Bernstein, A. M., Krauss, R. M., Kromhout, D., Jenkins, D. J. A., Malik, V., Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A., Mozaffarian, D., Yusuf, S., Willett, W. C., & Popkin, B. M. (2015). Food Consumption and its Impact on Cardiovascular Disease: Importance of Solutions Focused on the Globalized Food System A Report from the Workshop Convened by the World Heart Federation. In Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Vol. 66, Issue 14, pp. 1590–1614). Elsevier USA. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.050

- Malhotra, A., Redberg, R. F., & Meier, P. (2017). Saturated fat does not clog the arteries: Coronary heart disease is a chronic inflammatory condition, the risk of which can be effectively reduced from healthy lifestyle interventions. In British Journal of Sports Medicine (Vol. 51, Issue 15, pp. 1111–1112). BMJ Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097285

- Schwingshackl, L., & Hoffmann, G. (2012). Monounsaturated fatty acids and risk of cardiovascular disease: Synopsis of the evidence available from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. In Nutrients (Vol. 4, Issue 12, pp. 1989–2007). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu4121989

- Aune, D., Giovannucci, E., Boffetta, P., Fadnes, L. T., Keum, N. N., Norat, T., Greenwood, D. C., Riboli, E., Vatten, L. J., & Tonstad, S. (2017). Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(3), 1029–1056. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw319

- Akil, L., & Anwar Ahmad, H. (2011). Relationships between obesity and cardiovascular diseases in four southern states and Colorado. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(4 SUPPL.), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2011.0166

- Abbot, N. C., Stead, L. F., White, A. R., & Barnes, J. (1998). Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. In The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001008

- Varghese, T., Schultz, W. M., McCue, A. A., Lambert, C. T., Sandesara, P. B., Eapen, D. J., Gordon, N. F., Franklin, B. A., & Sperling, L. S. (2016). Physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease: Implications for the clinician. Heart, 102(12), 904–909. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308773

- Micha, R., Michas, G., & Mozaffarian, D. (2012). Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes - An updated review of the evidence. In Current Atherosclerosis Reports (Vol. 14, Issue 6, pp. 515–524). NIH Public Access. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-012-0282-8

- Zazpe, I., Beunza, J. J., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Warnberg, J., De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C., Benito, S., Vázquez, Z., & Martínez-González, M. A. (2011). Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in the SUN Project. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65(6), 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.30

- Estruch, R., Ros, E., Salas-Salvadó, J., Covas, M.-I., Corella, D., Arós, F., Gómez-Gracia, E., Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V., Fiol, M., Lapetra, J., Maria Lamuela-Raventos, R., Serra-Majem, L., Pintó, X., Basora, J., Angel Muñoz, M., Sorlí, J. V, Alfredo Martínez, J., & Angel Martínez-González, M. (2013). Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet. In Zeitschrift fur Gefassmedizin (Vol. 10, Issue 2, p. 28). Massachusetts Medical Society. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1200303

- Liyanage, T., Ninomiya, T., Wang, A., Neal, B., Jun, M., Wong, M. G., Jardine, M., Hillis, G. S., & Perkovic, V. (2016). Effects of the mediterranean diet on cardiovascular outcomes-a systematic review and meta-analysis. In PLoS ONE (Vol. 11, Issue 8). Public Library of Science. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159252

- Huedo-Medina, T. B., Garcia, M., Bihuniak, J. D., Kenny, A., & Kerstetter, J. (2016). Methodologic quality of meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease outcomes: A review. In American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 103, Issue 3, pp. 841–850). American Society for Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.112771

- Rees, K., Hartley, L., Flowers, N., Clarke, A., Hooper, L., Thorogood, M., & Stranges, S. (2013). “Mediterranean” dietary pattern for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Vol. 2013, Issue 8). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009825.pub2

- Zaccai, J. H. (2004). How to assess epidemiological studies. In Postgraduate Medical Journal (Vol. 80, Issue 941, pp. 140–147). The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2003.012633

- PAGE, I. H., STARE, F. J., CORCORAN, A. C., POLLACK, H., & WILKINSON, C. F. (1957). Atherosclerosis and the fat content of the diet. Circulation, 16(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.16.2.163

- Patino, C. M., & Ferreira, J. C. (2018). Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: Definitions and why they matter. In Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia (Vol. 44, Issue 2, p. 84). Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562018000000088

- Piepoli, M. F., Hoes, A. W., Agewall, S., Albus, C., Brotons, C., Catapano, A. L., Cooney, M. T., Corrà, U., Cosyns, B., Deaton, C., Graham, I., Hall, M. S., Hobbs, F. D. R., Løchen, M. L., Löllgen, H., Marques-Vidal, P., Perk, J., Prescott, E., Redon, J., … Gale, C. (2016). 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. In European Heart Journal (Vol. 37, Issue 29, pp. 2315–2381). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106

- Willett, W. C. (2012). Dietary fats and coronary heart disease. In Journal of Internal Medicine (Vol. 272, Issue 1, pp. 13–24). J Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02553.x

- Castelli, W. P., Anderson, K., Wilson, P. W. F., & Levy, D. (1992). Lipids and risk of coronary heart disease The Framingham Study. Annals of Epidemiology, 2(1–2), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/1047-2797(92)90033-M

- Menotti, A., & Puddu, P. E. (2015). How the Seven Countries Study contributed to the definition and development of the Mediterranean diet concept: A 50-year journey. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 25(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.12.001

- Safouris, A., Tsivgoulis, G., Sergentanis, T., & Psaltopoulou, T. (2015). Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Dementia. Current Alzheimer Research, 12(8), 736–744. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205012666150710114430

- Benson, G., Pereira, R. F., & Boucher, J. L. (2011). Rationale for the use of a mediterranean diet in diabetes management. Diabetes Spectrum, 24(1), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.24.1.36

- Schwingshackl, L., Schwedhelm, C., Galbete, C., & Hoffmann, G. (2017). Adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. In Nutrients (Vol. 9, Issue 10). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9101063

- Dontas, A. S., Zerefos, N. S., Panagiotakos, D. B., & Valis, D. A. (2007). Mediterranean diet and prevention of coronary heart disease in the elderly. In Clinical interventions in aging (Vol. 2, Issue 1, pp. 109–115). Dove Press. https://doi.org/10.2147/ciia.2007.2.1.109

- Boucher, J. L. (2017). Mediterranean eating pattern. Diabetes Spectrum, 30(2), 72–76. https://doi.org/10.2337/ds16-0074

- Fulkerson, J. A., Story, M., Mellin, A., Leffert, N., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & French, S. A. (2006). Family Dinner Meal Frequency and Adolescent Development: Relationships with Developmental Assets and High-Risk Behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.026

- Dunn, C., Haubenreiser, M., Johnson, M., Nordby, K., Aggarwal, S., Myer, S., & Thomas, C. (2018). Mindfulness Approaches and Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Weight Regain. In Current obesity reports (Vol. 7, Issue 1, pp. 37–49). Curr Obes Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-018-0299-6

- Dernini, S., & Berry, E. M. (2015). Mediterranean Diet: From a Healthy Diet to a Sustainable Dietary Pattern. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2015.00015

- Keys, A., Menotti, A., Aravanis, C., Blackburn, H., Djordevič, B. S., Buzina, R., Dontas, A. S., Fidanza, F., Karvonen, M. J., Kimura, N., Mohaček, I., Nedeljkovič, S., Puddu, V., Punsar, S., Taylor, H. L., Conti, S., Kromhout, D., & Toshima, H. (1984). The seven countries study: 2,289 deaths in 15 years. Preventive Medicine, 13(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-7435(84)90047-1